HERITAGES OF VIOLENCE

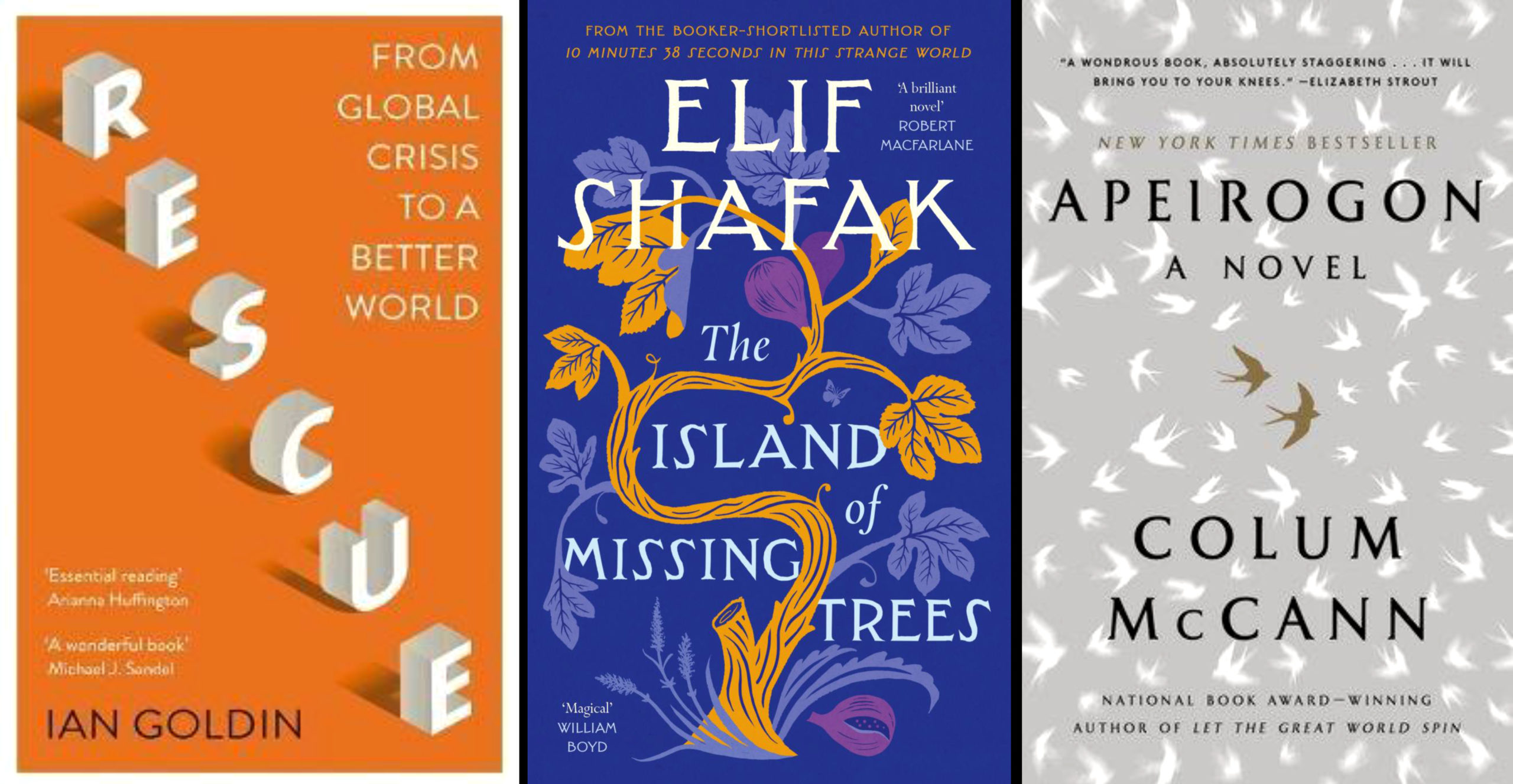

Rescue remedies for ‘an equality of pain’: a review of ‘Apeirogon’, ‘The Island of Missing Trees’ and ‘Rescue’

‘Anyone who expects love to be sensible has never loved,’ writes Elif Shafak in her latest novel.

I have a theory that books always choose me. At the right time a book will insinuate itself into your life by a series of chances and coincidences. If it succeeds it will bring wisdom, tenderness and explanations that your everyday soul may have been searching for.

This has happened throughout my life and it happened again recently, but this time it was three books.

The first two, Colum McCann’s Apeirogon and Elif Shafak’s The Island of Missing Trees are both Covid babies, but neither is “about” Covid. They are novels that by pure coincidence (as far as I know) have shared themes, so much so that they almost feel as if they are talking to each other. Yet they are as different as they are similar; perhaps it’s the Mediterranean coast and air that envelops both their settings (to the extent that they have “settings” because the fluidity of time and geography is a theme of both books) in Israel/Palestine and Nicosia, Cyprus.

Shafak’s story is of magical realism. It’s a love story at heart, between a Turkish Cypriot woman, Defne, and a Greek Cypriot man, Kostas Kazantzakis. As young people, they fall in love in the kindlings of the 1974 civil war in Cyprus, get torn apart, then fall in love again in the embers of its aftermath. It’s about the love between two men, between a Fig Tree and the people it shades, between a daughter and her father. It’s about love in a time of hate, and how hate insinuates itself into love, relationships and ultimately their offspring. “Girdling” is what happens to some people in whom love and hate collide, but I’ll leave you to discover that unusual word’s meaning.

The Fig Tree is at the centre of The Island of Missing Trees, and the story is entangled in its roots, trunk and branches. It is a thinking, sentient fig tree, prone to profound observations on human behaviour from its place of witness, noting, for example: “Humans are strange… full of contradictions. It’s as if they need to hate and exclude as much as they need to love and embrace. Their hearts close tightly, then open at full stretch, only to clench again, like an undecided fist.”

In contrast, McCann’s story is of realistic magic, a love story between two fathers, Bassam Aramin, a Palestinian, and Rami Elhanan, an Israeli, whose daughters were both, a decade apart, victims of the occupation and conflict waged by Israel on Palestine. Smadar was killed on 4 September 1997, aged 14, by a terrorist bomb; Abir on 16 June 2007, aged 10, felled by a young Israeli soldier’s rubber bullet.

Their short lives are the centre of the novel, akin to the Fig Tree.

Their deaths epitomise the banality of random and arbitrary hate, fuelled by senseless ethnic and intercommunal conflicts.

On the day of Smadar’s murder on Ben Yehuda Street, Tel Aviv, “she wore a pair of black jeans, a Blondie T-shirt, Doc Martens and a simple gold necklace”. Abir was crossing the street to her school, having just bought a “candy bracelet” at a local shop. “She wore her school uniform – a white blouse, a navy cardigan, a blue skirt with ankle-length trousers underneath, white socks, dark-blue patent shoes, slightly scuffed”.

One shoe was discarded as the bullet felled her. The candy bracelet outlived her.

Both books trigger a million thoughts and connections that, like the migratory birds they celebrate, cross time and geography. They evoke the minutiae of living and dying. McCann writes about the “sheer simultaneity of all things” and his book captures this. The Fig Tree puts it another way:

“Human-time is linear, a near continuum from a past that is supposed to be over and done with towards a future deemed to be untouched, untarnished.” By contrast, “Arboreal-time is cyclical, recurrent, perennial; the past and the future breathe within this moment, and the present does not necessarily flow in one direction; instead it draws circles within circles, like the rings you found when you cut us down.”

That is a perfect description of the structure of Apeirogon which, though based on a true story, is embellished, imagined, infused and layered with meanings. So too is The Island of Missing Trees, although Defne and Kostas never had a temporal reality outside Shafak’s preoccupation with human stories and connection as one means to survive our “age of anxiety” (something I have written about previously).

What traditional readers would consider the stories’ main plots are really just the tree trunks; the books are equally concerned with the roots, branches and leaves of life. The novels are attempts at forming an Apeirogon, described by McCann as “a shape with a countably infinite number of sides. From the Greek, apeiron: to be boundless, to be endless. Alongside the Indo-European root of per: to try, to risk.”

So, in keeping with its title, Apeirogon imitates the structure of life which, rather than being a longitudinal progression, particularly when that progression is halted early by murder, is a multiplicity of senses, memories, histories, influences all at work in the same moment, place and, whether you are conscious of it or not, person.

It evokes “limitless nature”: in the skies above Tel Aviv and the occupied West Bank are numerous species of birds; on The Wall that separates Israelis and Palestinians is a subversive Bansky painting; in Smadar’s walkman there’s the music of Sinead O’Connor’s album I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got; in Bassam’s memory are the legends of The Thousand and One Nights, the destruction and reconstruction of the Saldin Pulpit, the assasination of Wael Zwaiter… all fuse and all are linked.

But both books are so much more than abstract musings on our existence. They are deeply moving stories of love and loss, that celebrate agency; they are tales about human conflict and tragedy, how some escape it and some can’t; and of the noble efforts of activists in both countries (the Committee of Missing Persons in Cyprus and the Parents Circle Family Forum in Israel/Palestine) to build bridges across ancient but unnecessary enmities.

Rami and Bassam are people who “use the force of grief as a weapon”; they are on a voyage of discovery. Bassam, for example, reflects how while he was in prison “I read more and more about non-violence and political engagement. I began to realise that violence is exactly what our opponents wanted us to use. They prefer violence because they can deal with it. They are vastly more sophisticated with violence. It’s non-violence that is hard to deal with, whether coming from the Israelis or Palestinians or both. It’s confusing to them.”

Finally, an overarching theme that binds the two books is their shared sensibility to our natural world.

The birds that migrate over Israel, pass over Cyprus too, the same sea laps at their shores. They reflect on how humans have separated themselves from all other species (“most arboreal suffering is caused by human kind”, says the Fig Tree), yet are not intrinsically different from all that surrounds us – although we think we are.

What traditional readers would consider the stories’ main plots are really just the tree trunks, the books are equally concerned with the roots, branches and leaves of life. (Photo: homestratosphere.com/Wikipedia)

Nature is not depicted or felt by the authors as if it is something external to us, instead it inhabits our pores, permeates our conscious and subconscious. It is the antidote to hate, the place where we may recover our souls by emulating rhythms and patterns of life that humans once shared with all other life forms, but from which we have been driven further as our societies, and therefore each of our individual beings, succumbed to the illogical logic of ceaseless competition and consumption.

We need to make reparations for the harm we have inflicted on other species, not just each other, we need to decarbonise as much as we need to decolonise.

We need rescue.

Which brings me to the third book.

Rescue, From Global Crisis to a Better World by Oxford University Professor of Globalisation and Development Ian Goldin, found a place in this books’ reflection by coincidence. It was already in my hands when the other two came along and displaced it.

I have struggled with it. Not because it’s not an outstanding piece of research on the manifold ways in which the Covid-19 pandemic has changed our world and deepened inequality and despair. It is one of the best and a must-read. But, like so many other outpourings by academics on inequality, it’s so dry that its cerebrality numbs the heart. It lacks arborescence. One thing academics and activists should know by now is that a tome of facts and evidence, however powerfully conjoined, are not enough to stir humanity to struggle for a better world. As Goldin says:

“The pandemic has revealed what is most valuable in our lives. The task now is to ensure that this is reflected in our personal priorities and in the actions of our governments.”

Or, as Shafak would say, connection is critical.

This is why, in the midst of the assembling of so many facts, the joining of so many dots, one of the sections in Rescue that most struck me was a chapter on Work for All. It reports that:

“During the Great Depression President Roosevelt paid artists to paint and write for their country… the income generated by museums and the hundreds of thousands of visitors who travel to see these and other artists’ work has repaid the investment thousands of times over and, through both the income and the creative inspiration generated by their work, spread the benefits much more widely.”

Says Goldin: “The contrast between Roosevelt’s visionary response and that of today could not be greater.”

And there’s the rub. Human agency and activism are desperately needed to change the world. But, in my humble opinion, it is stories by writers like Shafak and McCann that offer the deepest insights into the roots of our crisis. It is through the affirmation of our humanity, our oneness with our planet, that we stand the best chance of rallying against the destructive forces that are propelling us towards catastrophe. That is why struggles for reading and quality basic education, for funding of the arts, for the massification of theatre and drama, for freedom of expression, for health and sufficient body and soul-food, seem to me to be so crucial to the moment. DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.