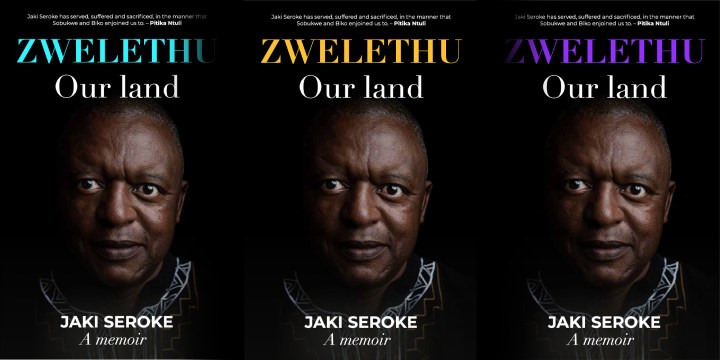

BOOK INTERVIEW

Zwelethu: Our Land — A story of struggle, conflict and family

Jaki Seroke’s memoir traces his life as an anti-apartheid activist, his time on Robben Island and how this affected his family life.

“You could have said my life was cast in stone. I knew that I was certainly going to acquire a degree at the University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland, become a teacher or train for the priesthood, but certainly become a professional. Raise a family. Live happily ever. Then the student uprisings of 1976 happened. I was shaken out of my reverie. I realised that history had a mission for me,” writes Jakie Seroke in his memoir, Zwelethu: Our Land.

A calling and an unavoidable mission are how Seroke, a Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) anti-apartheid activist, described why he joined the fight against the regime.

“With this book, I wanted to write about the ordinary people who were in the struggle. Many people made many sacrifices and I wanted to document that,” said Seroke about his first book.

The book traces Seroke’s life from his childhood in Soweto to the 1976 Soweto uprising, to his work at Raven Press and other arts organisations, his arrest and how he navigated trying to build a family while doing political work.

Growing older and understanding the socio-political context that Seroke lived in led him to conclude that “ours was a wretched rat’s life”.

As a young, black boy, growing up in apartheid South Africa, Seroke writes that he felt that his future was bleak. All he had to look forward to, if anything, was a life of servitude to white people, of being inferior and constantly violated.

In the book, Seroke is candid about his dedication to anti-apartheid activism and his desire to have a healthy, fulfilling romantic relationship.

“A lot of the time our work was done secretly. Often, our families and our partners were under surveillance. Sometimes, it felt like being in the struggle meant you had to put aside your interest in raising a family which was a difficult thing to think about,” said Seroke.

Seroke writes about his comrade, Thami Mnyele, and how he saw Mnyele’s relationship with his partner, Naniwe, as what millennials today would refer to as “relationship goals”.

Their relationship made Seroke believe that a good, functional relationship between two black people was possible in the depraved world they lived in.

But political activism meant that many sacrifices had to be made. Seroke writes about witnessing Naniwe arriving home to a letter from Mynele informing her that he’s left the country because his work had been compromised by the authorities.

Reading the passage, one is transported to that moment. The day starts out as ordinary as any other but ends with Naniwe’s life being dramatically altered. It serves as another example of Seroke witnessing the difficult sacrifices anti-apartheid activists had to make to further the political cause.

Being in the liberation movement came with severe challenges, ranging from internal squabbles among activists, personality clashes, and cases of people being tortured before becoming police informants.

Seroke writes in detail about the shock and betrayal he felt whenever he found out someone he thought was a comrade was actually in cahoots with the police.

At this point, Seroke was part of the PAC, which he believed aligned more with his politics than the ANC. Seroke was also invested in using the arts as a form of anti-apartheid activism.

“The contribution of the arts was undermined by liberation movements and they often had a tendency to say the arts didn’t contribute a lot. Poetry performances, literary journals and theatre were way more powerful than soapbox speeches when it came to connecting to people and teaching them about our cause,” said Seroke.

Although being an anti-apartheid activist required Seroke to frequently travel to secret meetings and cross borders — for which he was often detained, this didn’t stop him from wanting to settle down and have a family life.

“We were in our youth,” he says with a chuckle, “you’d fall in love and you can’t stop that from happening. You also had your family asking you about marriage and kids. My peers were also getting married so I, also, got to a point where I thought I had to settle down.”

He eventually met and later married Dikonelo, in 1985. However, the bliss of his new marriage was cut short in 1986 when, at the age of 27, Seroke was arrested. He was charged for engaging in terrorism and belonging to a banned organisation.

Seroke was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment, 1,000 kilometres away on Robben Island.

During Dikonelo’s visit to Seroke on Robben Island, she was frank with him, saying she “was not impressed with my new status as a hero of the struggle. Nor was she going to spend 10 long years waiting for me to be released,” writes Seroke.

“Being in prison was very frustrating. I don’t like the idea of jailing people because you’re stuck in a moment,” said Seroke.

In his chapter on being on Robben Island, Seroke lays bare the difficulties of being stripped away from his community.

“But what was interesting about Robben Island was that you had young and old people from all corners of the country there. There were even counsellors to counsel us regarding our marital problems,” said Seroke.

Seroke mentions some familiar names, such as the current police minister, Bheki Cele, who had been sentenced to imprisonment on Robben Island in 1987. Cele shared with Seroke that once he was released, he would be going on a sea cruise with his wife.

In the book, Seroke doesn’t disclose what he was looking forward to upon his release. “That’s probably because I didn’t think I’d be released any time soon,” said Seroke.

Meanwhile, outside of Robben Island, Nelson Mandela — who had been incarcerated there for 27 years — had started talking to FW de Klerk’s government regarding a new South Africa.

The talks started in 1989, a year before Mandela was released.

In 1991, Seroke was released. “Being released from Robben Island was one thing. But people were still dying, things were getting worse. In Robben Island, we were in a contained environment and now you have to go out there,” said Seroke.

“When I came out, my wife said that I was a different person. As political prisoners, we spoke all the time about any topic, we’d talk about nature, psychology, anything. Now you come back to your family and they’re not interested in those things,” said Seroke.

At that time Codesa talks for a new, democratic South Africa were underway. At one point, the PAC delegates had stormed out of the Codesa meetings.

“The PAC delegates, led by advocate Dikgang Moseneke, said their proposals had been rejected out of hand by the ANC, the government representatives and a host of Bantustan political parties,” writes Seroke.

“Codesa was a mess, a kaleidoscope of ethnic and racial interests aiming to set up a confederate state called a new South Africa,” writes Seroke.

Speaking over the phone about Codesa, Seroke sounded deflated. “Codesa wasn’t based on anything other than a rush for change. The core issues were never resolved, issues about land and addressing social ills weren’t addressed. The Boers were still running the army, they continued killing and they were protected. How can you protect killers?” Seroke questioned.

After 1994, Seroke worked in the corporate world but remained involved with the PAC. Seroke insists that the PAC remains relevant in South Africa. “It will always be relevant because the party speaks to the issues of land and identity,” said Seroke.

But Seroke believes that the PAC’s role in the struggle hasn’t been adequately commemorated. In terms of preserving PAC’s history and their leaders, “the ANC tells us to promote our own leaders, even though they’re in government”, said Seroke. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.