BOOK EXCERPT

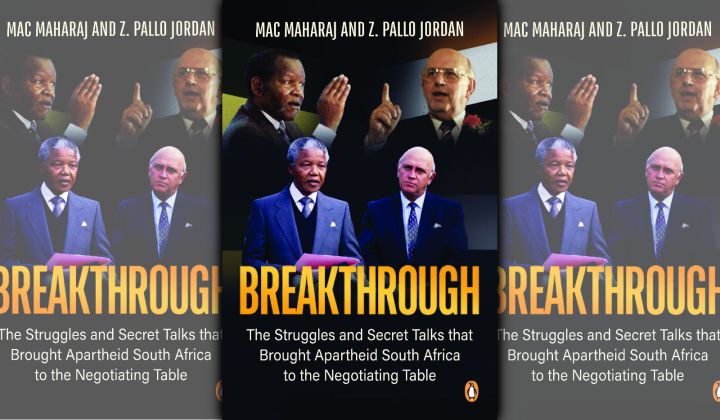

Mandela’s secret meetings revealed in Breakthrough by Mac Maharaj and Z Pallo Jordan

‘Breakthrough’ by Mac Maharaj and Z Pallo Jordan demonstrates that the events that preceded the formal talks of 1990–1994 are crucial for a full understanding of South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy.

Written by two ANC veterans who were close to these events, Breakthrough sheds new light on the process that led to the formal negotiations. The book focuses in particular on the years 1984–1990 and on the skirmishes that took place in the shadows, away from the public glare, as the principal adversaries engaged in a battle of positions that carved a pathway to the negotiating table.

The book draws on material in the prison files of Nelson Mandela, minutes of the meetings of the ANC Constitutional Committee, notes about the Mells Park talks led by Professor Willie Esterhuyse and Thabo Mbeki, communications between Oliver Tambo and Operation Vula, the Kobie Coetsee Papers, the Broederbond archives and numerous other sources.

***

Who blinks first?

One of the hurdles in any attempt to end conflict through negotiation is who among the protagonists will make the first move. Usually, this is seen as a sign of weakness and is framed around the question: who blinks first? Mandela believed that his isolation afforded him the freedom to take the first steps. It “furnished my organisation with an excuse in case matters went awry: the old man was alone and completely cut off, and he took his actions as an individual, not as a representative of the ANC”.

By the end of 1985, South Africa was in the grip of a partial state of emergency. The country was burning. The news of Mandela’s hospitalisation from 3 to 23 November at Volks Hospital caused alarm among cabinet ministers, who feared that in the event anything went wrong, they would shoulder the blame. The commanding officer of Pollsmoor Prison warned that civil war would break out if Mandela died. Kobie Coetsee paid him an unannounced “courtesy” visit. Mandela had not received a reply to an earlier request to see Coetsee and he now suspected the minister “might want to make some kind of deal, but he did not let on”.

Upon his discharge from hospital, Mandela was separated from his comrades in Pollsmoor and housed on the ground floor with three large cells all to himself – one for sleeping, one for exercise and one for studying. They were damp, dark and bleak, with hardly a view. When he saw his comrades a few days later, they told him the regime was trying to divide them and that they wanted to object to his isolation. Mandela thought differently. His focus was not on himself and his plight. He did not complain about being segregated from his comrades. “Something good may come of this,” he told them.

Mandela read his isolation as signalling the arrival of the moment to engage the regime and persuade them it was time to talk to the ANC. He did not consult his four comrades, because he feared they would veto his decision. Mandela knew that such a step did not contradict the longstanding strategy of the liberation struggle, but he took the precaution of sending a message via George Bizos to Tambo, reassuring him that he would not commit to anything without the approval of the ANC. With the green light from Tambo, he was ready to make his move.

It was while Mandela sought to reassure Tambo that the EPG made its first visit to South Africa in February 1986. As we have seen, their shuttle diplomacy ended when South African military forces raided Lusaka, Harare and Gaborone in May. The idea of talks was over. In June 1986, Botha embarked on a total crackdown when he imposed a nationwide state of emergency.

Mandela wrote two further letters to Kobie Coetsee, to which there was no response. Although Coetsee had a mandate from Botha to find a way out of the impasse, he was hesitant to engage with Mandela. In April 1986, Coetsee requested the South African Law Commission “to investigate and make recommendations regarding the definition and protection of group rights … and the possible extension of the existing protection of individual rights”. The Broederbond, under the chairmanship of Pieter de Lange, was in the throes of discussions that culminated in a position paper in June 1986. The intelligence services were also monitoring developments closely and keeping as fully informed as possible of the meetings held by the stream of delegations visiting Lusaka and elsewhere to engage with the ANC. And Coetsee was aware of Mandela’s willingness to use the EPG “negotiating concept” as a starting point for negotiations to begin.

Mandela persisted. In June 1986, he asked to see the commissioner of prisons, Lieutenant General Willemse, whose headquarters were in Pretoria. Within four days, Willemse was in Cape Town. Mandela asked him to forward a request for a meeting with the state president. Willemse phoned Coetsee, who ordered that Mandela be brought immediately to his residence, Savernake, in the Groote Schuur ministerial estate. The two talked for three hours and over two successive days. Then the contact ceased. Mandela wrote to Coetsee once more, but there was no response.

Then, just before Christmas, the deputy commander of Pollsmoor casually suggested that he and Mandela take a drive through the city of Cape Town. Over the next few months, there were more such sightseeing trips. Mandela speculated: “I sensed they wanted to acclimatise me to life in South Africa and perhaps at the same time, get me used to the pleasures of small freedoms that I might be willing to compromise to have complete freedom.” Mandela was now allowed more visits from family and friends too.

Contact between Coetsee and Mandela resumed in early 1987 just as abruptly as it had stopped in 1986. They met three times during the year at Savernake, followed by a meeting on 6 October at Kommaweer, a guesthouse meant for visiting generals in the Pollsmoor prison complex. These talks played a part in the regime’s decision to free Govan Mbeki and Harry Gwala on 5 November 1987. The administration was feeling its way around how to manage and manipulate the inevitable release of Mandela himself. For Mandela, his release from prison could not be a standalone event. It had to be part of a broader process leading to the ending of the conflict that had brought them to prison in the first place.

Before his release, Mbeki was taken from Robben Island prison to meet Mandela, who briefed him about his talks with the regime. Mbeki was unhappy that Mandela had not fully confided in him, and he made it known to many leading activists after his release.

The dilemmas facing the regime, and Coetsee in particular, are perhaps best captured in an appraisal of the political climate during 1987 by an unnamed NIS source:

South Africa finds itself, internationally and nationally, in a dead-end street. The sole question is how it can get out of the dead-end street with a modicum of political self-respect. The key is to talk with Nelson Mandela and to release political prisoners. He has become the international and national face of freedom and of the wickedness of apartheid. Talking with Mandela is the only way out. Mandela is now South Africa’s most influential and powerful leader. The only question is who should speak with him, when and about what. Is this possible? What kind of process and by whom should it be set in motion by us [sic] in order to bring about a negotiating table?

Until this moment, the idea had been to trade Mandela’s release for his co-option. Now a shift was taking place in their thinking. What were the prospects for negotiations with Mandela among those at the table? Who else in the ANC could be part of the process? Coetsee knew it was time to get down to talking seriously with Mandela by adding an additional strand in the form of talks between Mandela and a committee led by Dr Niël Barnard, the head of the NIS. Coetsee’s advice was that this committee’s talks should “demystify” Mandela.

According to Willie Esterhuyse and Gerhard van Niekerk in their book Die Tronkgespreke, President Botha met with Coetsee, Barnard and director general of justice SS ‘Fanie’ van der Merwe in his office and informed them that he was setting up a working group. Its task would be to think of a strategy and tactics for the release of Mandela and the other Rivonia Trial prisoners. The team would consist of Barnard, who would head it, Van der Merwe, Lieutenant General Willemse, and Mike Louw, the deputy director of the NIS. The first formal meeting between Mandela and this committee took place on 25 May 1988.

Mandela later wrote that he was “disturbed” when he learned that Barnard would be part of the team. “His presence made the talks more problematic and suggested a larger agenda. I told Coetsee that I would like to think about the proposal overnight.” But Mandela ultimately concluded that “my refusing Barnard would alienate Botha … If the state president was not brought on board, nothing would happen … I sent word to Coetsee that I accepted his offer.”

There is some confusion about how, why and to what extent Niël Barnard replaced Coetsee. The letter Coetsee wrote to Botha on 14 March 1986 makes it clear that he and Botha had agreed that he would engage with Mandela on the understanding that this was kept separate from other initiatives. Documents in the Kobie Coetsee Papers indicate that Mandela and Coetsee engaged in substantive discussions material to the regime and the ANC reaching the negotiating table. Yet Coetsee did not attend any of the meetings held by Barnard’s team with Mandela. Barnard acknowledges that there were “sporadic meetings … over the next three years” between Mandela and Coetsee. Of the document that Mandela wrote in preparation for a possible meeting with Botha, Barnard writes that “Mandela only gave us the document at the end of July 1989 but it had been sent several months earlier, without my knowledge, via Minister Kobie Coetsee to the president.”

Prison records show that between 1985 and 12 December 1989 Coetsee and Mandela met at least fifteen times. During April 1989 – the month Mandela sent his document to Tambo – they met at least three times, on 19, 20 and 26 April, while Barnard and the prison commissioner met Mandela only once, on 12 April. It is possible that it was during this period that Mandela first sent his preparatory notes to PW Botha. Mandela may have sensed that Barnard wanted to control the process and claim principal credit for the negotiated transition, and therefore chose to use Coetsee as his intermediary instead.

By December 1989, the committee had met Mandela forty-eight times and, according to Barnard, “the first seeds of the peaceful revolution that was destined to change the history of South Africa forever had been planted in secret”. DM/ ML

Breakthrough by Mac Maharaj and Z Pallo Jordan is published by Penguin Random House SA (R280).Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This is useful background to the transition of 1994. A further, really powerful one is a 90 minute YouTube video being released on Heritage Day by African Enterprise, “The Threatened Miracle of South Africa’s Democracy” – which reaches from the early human invasion of SA, through quite eye-popping accounts of the transition, to the current situation and the effect of the recent riots.