Maverick Life

Never forget to read the nutrition labels at the back of your food package – you’ll thank yourself later

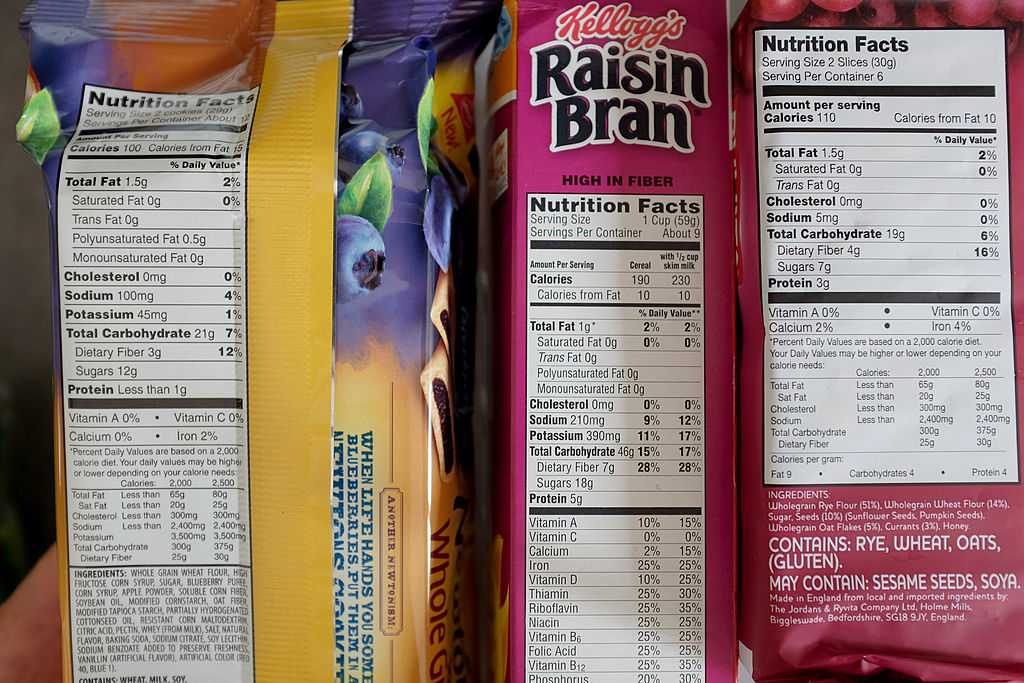

Many packaged food products contain labels with information about the contents of what we’re eating that can be confusing to interpret. We go behind the label to learn everything we can about what’s in our food.

Food labels are a legal requirement in South Africa: by law manufacturers cannot put unqualified or unsubstantiated information onto packaged foods. The R146, Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act of 1972 specifies the type of information that is and isn’t allowed on food products relating to definitions, provisions, nutritional information, claims, exceptions and other information.

According to an associate dietitian at Johannesburg-based Mbali Mapholi Inc, Yuri Bhaga, “Food labels ensure customers are able to make informed choices on the products they are buying.”

Cape Town-based dietician from The Pocket Dietician, Nicole de Klerk adds that “Nutrition labelling is a population-based approach, and when well defined it can have a positive influence on the diet of consumers.

“According to the World Health Organization, labelling is a tool that can be used to decrease diseases of lifestyle such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Studies have shown a consistent link between the use of nutrition labels and healthier food choices and diets. Those found to use nutrition labels were found to be more likely to eat healthier foods, have a reduced fat, sodium, cholesterol and energy intake as well as increased fiber, iron and vitamin C intake.

“Each individual manufacturer is responsible for writing their own labels, but there are strict regulations on what can and cannot be on a food label. Manufacturers have to adhere to the guidelines set out by the government which details each and every aspect of labelling.”

Food labels are usually found at the back of food packaging and contain information like ingredients, allergens, where the product was made, nutritional information, health claims, handling and storage instructions, and expiry dates.

“This information can help consumers make good and safe food decisions, for example to help prevent food-borne illness and allergic reactions,” says Bhaga.

“The labels literally tell you what you are eating,” says Gqeberha-based corporate dietician at Healthyworx, Riaan Van Der Walt. He adds that there are two main layers of information found on the back of food labels.

Layer one is a list of ingredients used to make up the food product, like sugar and salt, which are listed in descending order of quantity. The second layer of information is the table of nutritional information which breaks down the product contents into macronutrients (protein, carbohydrates, fat, sugar) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) as a result of the list of ingredients. According to De Klerk, the table of nutritional information allows the consumer to tell the proportions of the main ingredients such as sugar, salt, additives, and allergens in a food product.

De Klerk offers the example of unsweetened yoghurt, explaining: “When looking at the nutritional information table you may see sugar(g). However, there is no sugar in the ingredients list. The sugar on the nutritional label is the lactose – which is the naturally occurring sugar in dairy and not added sugars.”

The list of ingredients and the table of nutritional information are equally important parts of a food label in helping to better understand the product, says Bhaga. “It is important to know how to read the nutritional table and how to interpret the information provided, as not all information is as simple as it may seem.”

Let the “per 100g” column be your guide

So how do we actually read food labels?

De Klerk says that learning how to read a food label does not necessarily have to be difficult and when done right, is an empowering nutritional tool.

Next to the macro- and micro-nutrient column in the nutritional information table, you will find a “per 100g” column and a “per serving” column respectively.

De Klerk explains that the 100g column allows us to cross-compare food items. Bhaga adds, “When reading a food label you generally want to be using the ‘per 100g’ column when making decisions around the nutritional content as this allows for fair comparison to other products.”

The 100g column also allows us to determine what type of meal a packaged food product is. In other words, whether the product is a protein-rich meal, a sugar-rich meal, a fibre-rich meal.

The “per serving” column is the recommended serving size of the product. De Klerk explains that this value is determined by the manufacturer and is the serving size for a single serving. “It is important to note that the serving size is not personalised to individual needs,” she adds.

“Serving sizes differ greatly across brands and different types of foods and for the most part, people do not eat as per the recommended serving size so it is not a great estimate of the nutritional value of a product, unless you are looking at it in total isolation and will be consuming the serving sizes as listed,” adds Bhaga.

De Klerk and Bhaga agree that it helps to have a basic understanding of recommended amounts. Van Der Walt offers several points as a guideline:

“Fat is not nearly as important as most people believe. What is important is the amount of saturated fats. You want to minimise saturated fats to under 10% in your diet. For example, a food label that contains 10g or less out of 100g is optimal,” says Van Der Walt.

He adds that protein is important and that it is a good idea to stick to products that contain 10% protein or higher. The next ingredient we need to look out for, according to Van Der Walt, is sugar. “You want to limit the amount of sugar you consume in your diet … to approximately 10g per 100g or less.”

The excessive consumption of salt has been linked to hypertension (high blood pressure) – a cardiovascular disease that plagues South Africa to such an extent that a 2017 study conducted by the University of Witwatersrand found that South Africa has the highest incidence of hypertension in southern Africa.

Van Der Walt advises that we should try to limit our salt intake. “A gold standard to aim for is 120mg per 100g, and anything over 400mg should ultimately not be consumed.”

Another ingredient Van Der Walt says to steer clear of is trans-fatty acids which are found in packaged foods like biscuits, chips and pizza and have been linked to a slew of health risks from cardiovascular diseases to obesity.

“You will also notice that many food labels will report whether or not they contain trans-fats. These should be avoided at all costs,” says Van Der Walt. Trans-fats are usually oils that have gone through a process of hydrogenation in order to increase their shelf-life.

De Klerk points out that allergy sufferers need to be aware of any allergens a packaged product may contain. “Labelling regulations are strict with this and it is often well presented on the label,” she says.

“There is a lot of misinformation surrounding certain ingredients, but what these usually fail to highlight is the specific dose of these components which would need to be ingested for it to become harmful. The dose makes the poison,” Bhaga adds.

Health washing: Beware of marketing claims

While manufacturers are legally required to adhere to labelling legislation that is the R146, and that while the primary role of a food label may be to give us a better understanding of what we are eating, food labels also aid in selling the product.

Bhaga and De Klerk caution against sensational marketing claims and Van Der Walt adds that there is very little legally that governs what is put on the front of boxes and packaging.

“For the most part what is seen on the label can be held to be the truth. This is due to the fact that South Africa has fairly complex food labelling laws and regulations. However, there is also no single regulatory authority for food labelling in South Africa,” says Bhaga.

Because of this, it is easy for manufacturers’ marketers to make embellished claims in order to push their product, making space for a type of “health washing”.

There are three main types of “health washing” that, according to Bhaga, we need to watch out for.

The first one is food packaging copy that implies a food product is something it is not. “‘Low or reduced sugar’ is a common claim, but the nutritional information table often reveals that the quantity of sugar is still exceeding the recommended limit,” says Bhaga.

The second type of health washing is adding unnecessary claims to foods to make them more appealing to the consumer over competitor products. “Cooking oils claim to be cholesterol-free, when in reality all oils are by nature cholesterol-free.”

The third type of health washing to be aware of includes “gimmicky phrases and health-trending terms”, says Bhaga. “Many companies have recently started labelling their products ‘organic’, ‘natural’ or ‘plant-based’ as it is a popular shift in dietary preference.”

De Klerk adds that often manufacturers will use alternative names in place of, for example, sugar.

“There are many names for sugar and this often becomes difficult with label reading,” she says. “Sugar can be listed as glucose, dextrose, agave, fructose, honey, syrup, cane sugar, sucrose, coconut sugar… The same goes for salt – look out for ingredients such as sodium and monosodium glutamate (which is high in salt).”

De Klerk points out that the use of artificial sweeteners is also on the rise and often a point of confusion for consumers, leading to the misconception that sweeteners are healthier than sugars. She says this is not always true.

“Some products made with sweetener are often higher in fat and may still contain the same amount of calories (for example sugar-free chocolates). Some sweeteners also cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as gas, bloating and may have a laxative effect,” she adds.

For healthier alternatives, Van Der Walt recommends xylitol. “Xylitol is something that plants make although we don’t necessarily derive all of it from plants,” he says, “but it is a natural compound and although it does contain calories, it doesn’t mess with your blood sugar levels in the same way as traditional sugar does.”

However, there are two main issues with xylitol. First, research has shown that very small quantities of xylitol are toxic to dogs, and second, it is considerably more expensive than traditional sugars, fetching between R169 and R179.95 for one kilogram at Dischem, versus R26.99 for one kilogram of Selati white sugar from Shoprite.

Nutrition labels are seen on food packaging on February 27, 2014 in Miami, Florida. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Sell-by / use-by / best-before dates: Are we throwing perfectly good food away?

Another important piece of labelling information to look out for is date markings.

Although all three dieticians agree that date markings are not an exact science and should be used as a guideline rather than gospel, they serve an important purpose for consumer safety. “These dates also help manufacturers, suppliers and retailers to track sales, quality standards and knowing when to get stock on and off the shelves with the least amount of lost ‘fresh’ shelf time,” explains Bhaga.

Bhaga further unpacks the difference between the date markings. Sell-by dates are generally used by manufacturers to inform retailers how long the product should stay on the store shelf.

“Have you ever seen those discount shelves – it’s usually food that has reached its sell-by but not its best-before date,” says Bhaga, adding that best-before dates refer to the time period wherein the product is at its optimal quality and is not a direct indicator of whether the food is safe for consumption; and some foods, like coffee, can go well beyond this date.

“After its best-before date, a food item like coffee will still be fine to consume, albeit less flavourful,” says Bhaga. “This will also depend on whether the storage and handling has been done in the correct manner to preserve quality and safety of the food.”

Bhaga explains that the use-by date is a bit trickier and is usually found on highly perishable food items like meat, produce, dairy or ready-to-eat meals. This date is important because it relates directly to safety for consumption. “It is not legal to sell or donate food past this date as the safety of the food may have been compromised past this point.”

Van Der Walt says that we need to be very conscious of the number of food labels we find ourselves reading, as it could be an indication of the amount of processed foods in our diet.

“The moment a food label is required,” he says, “it could mean that you are not buying enough of what is referred to as ‘wholefoods’ which refer to food that comes straight from a farm, not a factory or production line, and contains minimal processing. Things like meat, dairy, fruit, veg, eggs.”

He adds that there are grey areas that include food items like bread. “Whole wheat, whole grain, and wholemeal bread are far less processed so we can lump them together with wholefoods,” he says. “White bread and white starches like chocolates, biscuits and cakes can be lumped together with ‘processed foods’ because they have gone through a high degree of processing and have the same effect as processed foods on our health.”

When it comes to food labels and healthy eating, Van Der Walt’s advice to navigate an ocean of false information and the thousands of products constantly being marketed at us is: “If you are reading too many food labels, you are already losing the game because it means you are eating predominantly production-line, processed foods and your diet needs to change.” DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

You do not say anything about the additives which are recognizable as starting with an E followed by a number or Calcium propionate which is added to bread to extend its shelf life.