Our Burning Planet OP-ED

Madagascar’s vanilla industry has become a magnet for corruption, money laundering and criminality

About 80% of the world’s vanilla is grown in the mountainous regions of Madagascar. Extraordinary price rises in recent years have brought rising criminality including organised and violent thefts, money laundering and related corruption. Now, in response to falling prices, the government has imposed minimum prices for exports, but this has provided an opening for new forms of money laundering and corruption.

This article appears in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin.

The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally. To receive monthly Risk Bulletin updates, please sign up here.

As much as 80% of the world’s vanilla is grown in the mountainous regions of Madagascar by smallholder farmers who must painstakingly pollinate each vanilla blossom by hand. A boom in vanilla prices — driven in part by low harvest years, rising demand for natural vanilla flavouring and speculation by intermediary buyers in the market — saw international vanilla prices increase tenfold between 2013 and 2018. At the peak of the boom in 2018, vanilla was traded internationally at prices higher than silver. The “vanilla fever” has made some producers rich, but has been described as a “short-lived El Dorado”, bringing with it insecurity, criminality and corruption.

Vanilla farmers have been subjected to organised thefts of their prize crop, some of which have ended in violence, either with farmers killed attempting to protect their produce or would-be thieves being executed in forms of mob justice. Reports have found the vanilla market to be a site of money laundering and of corruption.

Much of this turmoil has been centred in the Sava region, in Madagascar’s north-east, which for years has been the main region for vanilla production, and where up to 90% of the regional population are reliant on vanilla cultivation, according to the region’s governor. Yet as prices began to fall from their 2018 highs — to the point where, in February 2020, the government imposed a minimum price for exported vanilla in an attempt to stabilise the market — criminality in the vanilla trade has also changed. Thefts have begun to affect other nascent vanilla-producing regions, and new patterns of money laundering and corruption have emerged.

A bitter taste for farming communities

According to Captain Maurille Ratovoson, commander of the regional gendarmerie, law enforcement has recorded several types of criminality in relation to vanilla in the Sava region, particularly in Antalaha. Firstly, there are thefts of vanilla from the fields, which happen regularly between March and July at the time that the official harvest starts, and thefts of stored vanilla, ready for sale. These thefts can sometimes turn violent, as would-be thieves can be armed with long knives or firearms. The public prosecutor in Antalaha, Alain Patrick Randriambololona, confirmed these reports, adding that there have also been cases of poisonings and attempted murders during attempted vanilla thefts.

Secondly, there are scams and frauds carried out between the growers and the “collectors” (the intermediaries who collect vanilla from farmers), between collectors themselves and between the higher-level operators, who employ vanilla collectors and who also export vanilla. For example, vanilla collectors may take the produce yet never deliver on promised payments to growers. “These types of crimes rise particularly… before and after the official harvest,” says Ratovoson. “The victims take time to come forward because they are waiting on payments from the bigger operators” — payments that never appear.

For the governor of Sava region, Tokely Justin, the fight against vanilla thefts should not only be limited to police and the criminal justice system. He encourages collaboration between the vanilla operators and the local population. For Justin, this is a political priority, especially for the next harvest, which promises to be an abundant one.

For the governor of Sava region, Tokely Justin, the fight against vanilla thefts should not only be limited to police and the criminal justice system. He encourages collaboration between the vanilla operators and the local population. For Justin, this is a political priority, especially for the next harvest, which promises to be an abundant one.

But some farmers, faced with potentially devastating losses from theft, have turned to private protection. Romuald Bemaharambo, a farmer in the Sambava district of the Sava region, described the actions he must take to protect his crop. “We are obligated to pay guards during the nine months of vanilla growth until the harvest starts,” he said. “Personally, I pay around 400,000 ariary [around $100] each month to keep my plants, the flowers and especially the stocks of harvested vanilla from the moment that harvests are authorised, which is to say my annual expenses for security are around 3,600,000 ariary per year [just over $900]. It’s a significant sum, because at the moment with prices falling on the local market and the price limits on export, I find myself in the red!”

Bemaharambo produces 100‒150kg of vanilla annually on his farm, and last year sold at 800,000 ariary per kilo. This makes security for the farm between one-twentieth or one-thirtieth of his gross revenue.

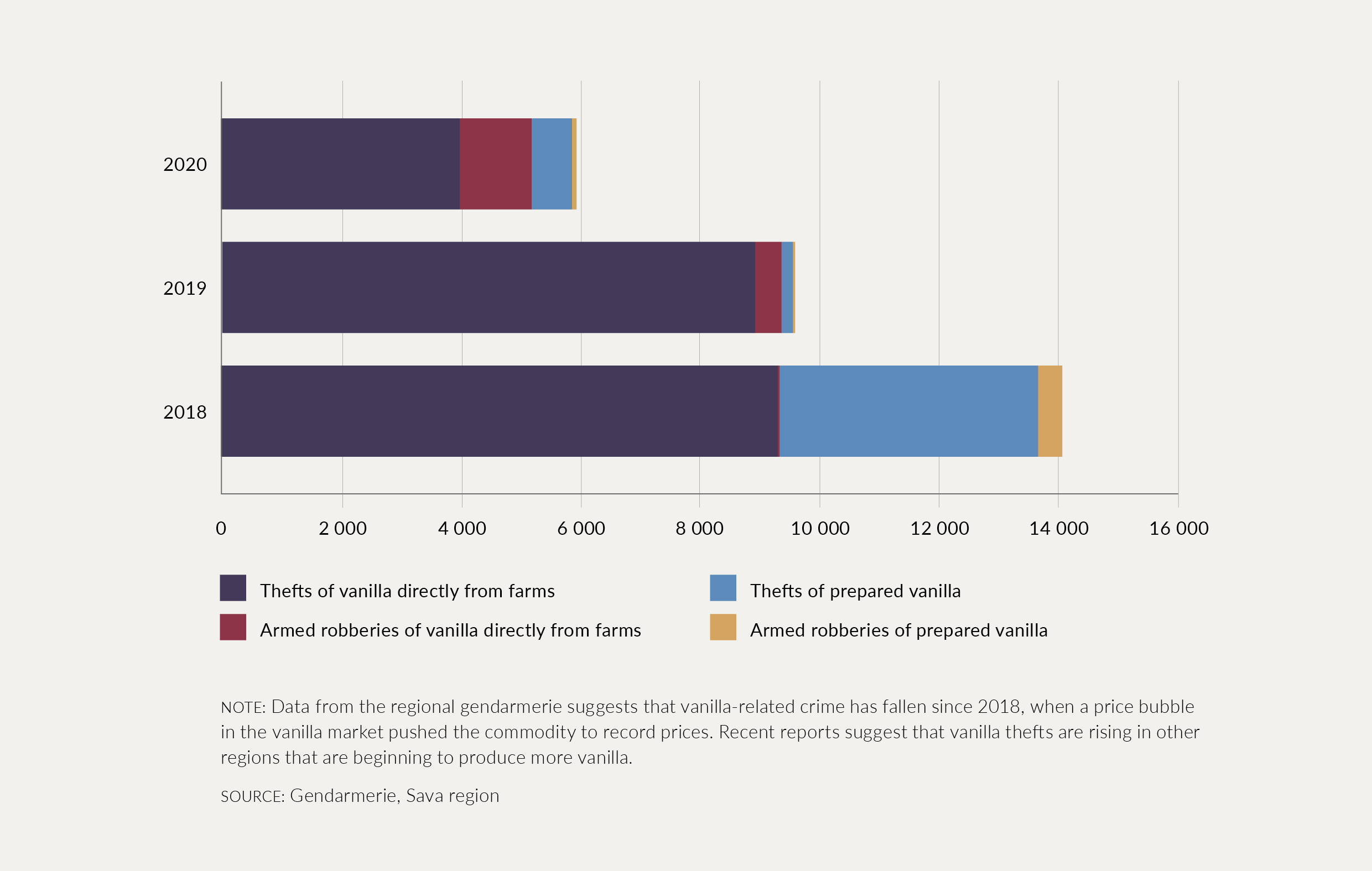

While the cost of such security leaves a bitter taste for farmers such as Bemaharambo, vanilla-related criminality in the Sava region is actually declining, according to statistics shared by the regional gendarmerie. Randriambololona, the prosecutor, attributes this to the regional authorities’ zero-tolerance approach towards vanilla-related crimes.

However, thefts have risen in up-and-coming vanilla-producing regions. According to growers in the Atsimo-Atsinanana region in the southeast of Madagascar, thefts of “green” vanilla directly from the plant are on the rise, especially just before harvest time. Victor Faniny, vice president of the region’s vanilla policy platform, confirms this trend, which stymies the development of the market, as vanilla picked early is of lesser quality.

According to Norbert Monja, a vanilla farmer in the southeast: “This situation affects the quality of the vanilla and the financial resources of households. On the one hand, we have to pick the vanillas early to avoid theft. On the other hand, we also pay security guards 300,000 ariary [$76] per person every three months. Since we do not yet have clients to buy our produce… we are in a loss-making situation,” he says.

There are allegations that these thefts are part of a strategic criminal approach that leaves the farmers little choice but to sell to criminal actors. Aline Harisoa, a representative of the Tsara Hevitsy association, part of a coalition of civil society organisations in Farafangana, southeast Madagascar, describes such an arrangement: “The mafias order the theft of vanilla… Then they themselves encourage the farmers to sell the vanilla, still on the plant, at derisory prices. Then, if this offer is accepted, the operators do not pay the agreed amounts at harvest time… abusing the population’s trust,” she says.

Colonel Derbas Behavana, commander of the National Gendarmerie in Farafangana, acknowledges that “the mafia networks are strong and tightly knit”, making it hard to identify those who are organising the thefts. However, law enforcement and judicial sources believe that a select few of the high-level vanilla operators are, in reality, the commanders of thieving gangs, either paying the thieves directly and buying stolen vanilla at bargain price or simply taking the stolen vanilla in return for a part in the profits. Local communities, elected officials and regional authorities in the southeast likewise argue that bands of thieves are paid and organised by vanilla operators from other regions, particularly the Sava region. Other intermediaries in the vanilla market are also suspected of covertly buying stolen produce and then selling it to operators for export at standard market price.

But such allegations may also have more complex motives. Competition between vanilla-growing regions drives suspicion between producers, leading them to accuse producers of other regions of masterminding the vanilla thefts. A high-level vanilla operator in Farafangana, who spoke to the Gi-Toc on condition of anonymity for his safety, said “we are victims of speculation and unfair competition from more experienced operators based in the Sava region or other producing regions. It should be remembered that there are currently more than 10 vanilla-producing districts in Madagascar. The Sava operators are afraid of the quality of our products and the quantities of our vanilla. So they seek to damage our image.”

Désiré Andriamarikita, mayor of the commune of Vohimalaza, Vaingandrano district, likewise believes that bad-faith operators from other regions are behind the thefts, attempting to harm the sector as it develops in the south.

Shifting patterns of money laundering

Activists and companies in the vanilla business have argued that vanilla prices have been artificially inflated by rosewood traders speculatively buying into vanilla as a form of trade-based money laundering and that the leading businesspeople controlling the vanilla trade are also trafficking rosewood. (The illegal trade in rosewood is one of Madagascar’s most significant illicit markets.)

Yet with vanilla prices falling, modes of money laundering have shifted. In an attempt to bring stability to the market, the Malagasy government imposed a legal minimum export price for vanilla from February 2020, first at $350 per kilogram, then $250 per kilogram. While the aim of this policy was to preserve the businesses of smallholder producers, there has been a sharp fall in prices on the domestic market as buyers, hesitant to export vanilla at a price higher than other international offerings, are unwilling to commit to buying produce. Debates between some growers who prefer to allow the market to regulate itself, and those in support of the minimum price have been fierce.

Two high-level vanilla operators speaking under condition of anonymity argued that the minimum price policy has given rise to a new form of corruption and money laundering. A select few vanilla exporters, they allege, have the privilege of exporting vanilla at $125–$150 per kilogram — well below the imposed minimum price. While the ability to export at a lower price may not seem like a privilege, it allows these exporters to sell at an internationally competitive rate, unencumbered by the regulations that are making international business difficult for other exporters. These exporters reportedly enjoy high-level protection and their (illegal) special status is widely known.

The means of disguising such transactions is relatively simple. Firstly, the exporter and overseas buyer agree on paper to a $250 per kilogram sale of vanilla. After the transaction is concluded, the Malagasy party returns the difference between the $250 per kilogram and the real (lower) price back to the overseas buyer. This may take place after the money is laundered through other business activities.

According to prominent environmental activist Clovis Razafimalala, founder of environmental watchdog group Coalition Lampogno, a significant number of major vanilla operators who are former rosewood traffickers have also been taking advantage of this scheme to launder the profits of rosewood trafficking. By exporting vanilla at $150 per kilogram, $100 of additional funds (in this case rosewood profits held in offshore accounts) is added to payments to reach the required $250 limit. This allows the profits of rosewood trafficking to be brought back into Malagasy banks without detection.

Madagascar is currently facing several considerable challenges: the financial and health impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and severe drought in some southern regions. It seems also that the vanilla market — one of the country’s key exports — is facing an uncertain time, as the rush of demand for the highly prized spice has engendered criminality and insecurity. DM

This article appears in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally. To receive monthly Risk Bulletin updates, please sign up here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.