OUR BURNING PLANET

Monkey Business (Part Three): Cape Peninsula’s dated baboon management plan is a failure, say critics

The way the baboons in the Cape Peninsula are managed is hailed as a great success, but not everyone agrees.

This is the final part of a three-part series looking at the management of baboons in the Cape Peninsula. Read Part One and Part Two

“I think because the programme is ‘sold’ as a science-based one, there should be clearly defined measurements of success of the baboon management programme,” said Jenni Trethowan, from the Baboon Matters Trust, which has been actively involved with the baboons for the past 25 years.

“It is important that people understand the different troops and their personalities. When I watched paintballing one day, it was chaotic. The juveniles were rubbing themselves as they came over the wall. They were being fired at from all over. If you are being shot at on the mountain and in the village, it makes no difference and they don’t know the difference,” she said.

She sees little tolerance for the natural behaviour of the baboons, or that the measures being used are working.

Professor Justin O’Riain, a behavioural ecologist at the University of Cape Town’s Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa, is the only consultant for the City of Cape Town. The city said in an email “he is a world-renowned primatologist and an independent researcher from UCT”.

When asked how he is scientifically measuring the success of the urban baboon management programme, he said:

Baboons and a monitor near Cape Point. (Photo: Gallo Images / Nardus Engelbrecht)

“This really depends on your definition of success. The Urban Baboon Programme (UBP) stated their goals and they have changed little from the Brownlie strategy (in 2000) which predates our involvement and the involvement of most people currently part of the UBP.

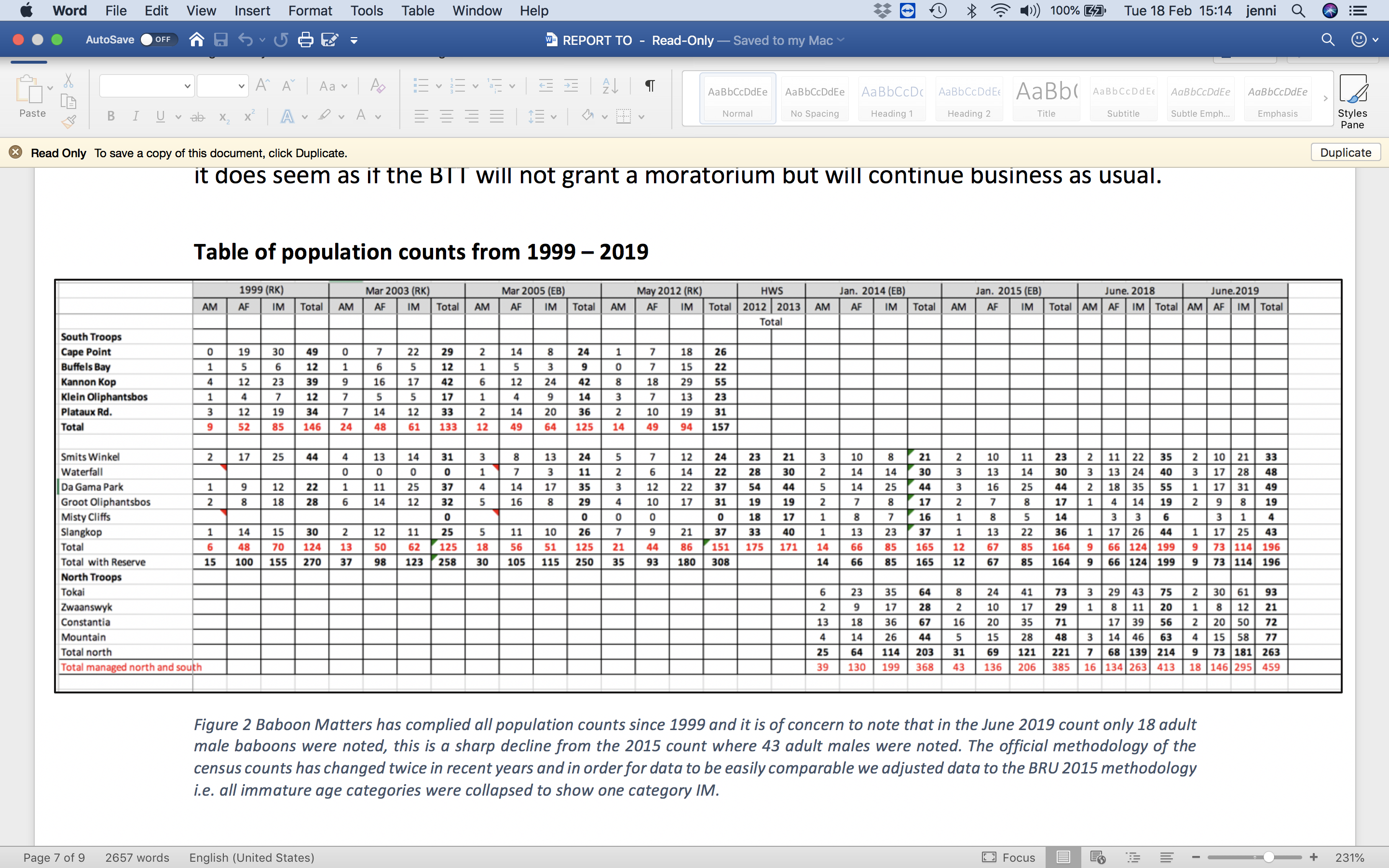

“The goal: to ensure a sustainable population with reduced conflict between humans and baboons. If that is the definition of their success, then yes, we can state unequivocally that the UBP has been successful. The population has increased by 58% from 1998 to 2020. The number of troops increased from 10 to 16. In 1998 there were a few troops with no adult males. In 2020 all troops had adult males. Then, as indicated in the previous section, the time that baboons have been spending in urban areas has declined and with that there has been reduced conflict. Less damage to houses, people, pets and less injuries and deaths to baboons.”

Trethowan, who keeps data on all the troops, said the strategy was written 20 years ago. She questions why it has not been updated, given the fact that there has been a lot of research done in the intervening years. Only 11 troops are managed and one troop in Misty Cliffs has been completely eliminated.

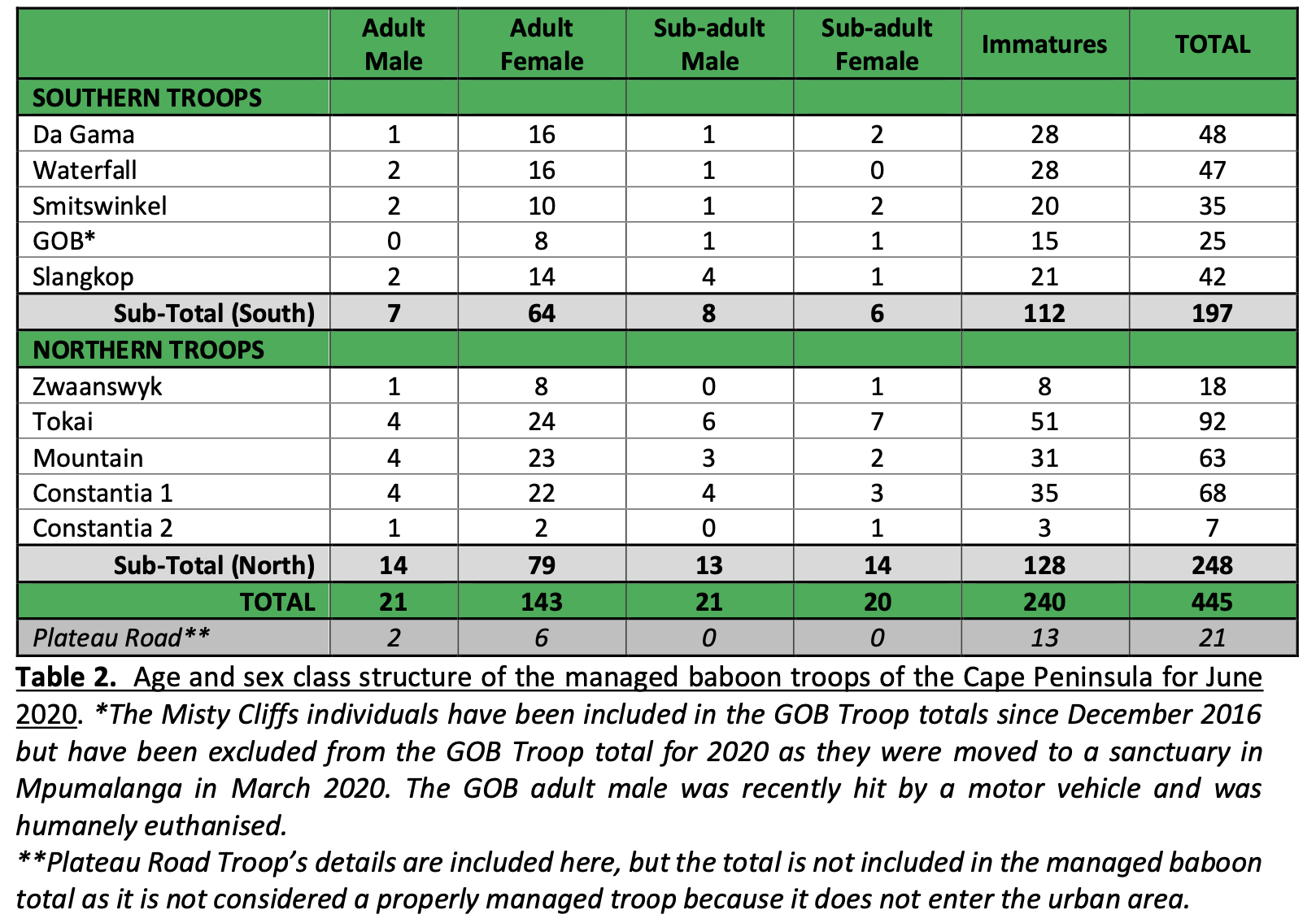

(See the population tables Baboon Matters kept for 2020 and the one for 1998 to 2019. Adult males, adult females and immature baboons are marked. There is a high number of immature baboons that do not reach adulthood, and the numbers shown to us by the managers is not necessarily a healthy population in terms of an increase in breeding adults.)

“The service providers show no adaptive management and do not encourage field staff or field management to be adaptive. For example, the last four females at Misty Cliffs foraged on easily accessible food at three Scarborough restaurants every morning. Instead of planning around this pattern, the rangers went up to the roost site every morning and the baboons then went directly to the restaurants. I suggested a couple of ideas to [Human Wildlife Solutions, HWS] but [they] dismissed them all. I think it was brutal on the men running up and down the cliff daily and achieving nothing,” said Trethowan.

O’Riain said: “However, if one’s definition of success is that baboons and people should share the urban environment ‘because baboons were here first’, then the programme is a failure, because it seeks to keep baboons in a natural habitat and out of urban areas where threats are known.

“Furthermore, if your definition of success is that the peninsula baboons should be managed as if they were in a sanctuary which includes feeding and providing them with veterinary care for even natural injuries, then you might consider the programme a failure. Lastly, if you believe that humans do not have the right to euthanise individuals with proven poor welfare to prevent suffering and acts of cruelty as the management guidelines suggest, then you will also consider the programme a failure.

“I think it is imperative to remember that the authorities are managing an ecosystem without natural predators. Thus, when a male is deposed as alpha and becomes peripheral to the troop, they invariably spend more time in urban areas while the core of the troop remains the focus of the field rangers and their efforts to keep them out of town. Such males start to roam alone and can more easily forage in urban areas. In a natural ecosystem, lone males would suffer high predation risk and hence there would be very few of them. Not so on the peninsula where there are no predators. Low-ranking peripheral females (who find life near the social centre tough as they are low in rank and hence constantly picked on) and old females or females in poor condition very often join such males enjoying greater access to rich pickings in urban areas and even copulations with the deposed male.”

This is how splinter troops form on the peninsula and with the single team of rangers focusing on keeping the majority in the main troop out, these splinters spend more time in town and with that, there are more injuries and deaths linked to urban causes, as a result of increased access to human foods and the higher risks of being closer to humans, according to O’Riain.

Pete Oxford, a zoologist who knows the baboons in Betty’s Bay well, said the only natural predator there has ever been in that area is the leopard. It is still there and only 5% of its diet is baboons. “All three of our adult males, who rotate through dominance, every few days are known to enter the house. Does he [O’Riain] think they should be killed? The troop has not formed splinter groups; they all sleep together. However, the troop is now being splintered on a daily basis by the aggressive chasing. This makes the management entirely ineffective.

“The method is failing and has led to an increase in house entries, despite all the money spent. There is too much in-house protectiveness and not enough objectivity.”

O’Riain said, for instance, that “Kataza could not persist on the peninsula once removed from Tokai where he was integrating well. He was taken to a sanctuary, and I believe is enjoying a good quality of life with lots of food, social interactions and no predators. The problem is this option is not sustainable and the sanctuary owners have stated this. Hence the public opposed to lethal management for a baboon that cannot be deterred from dangerous urban areas must fundraise and build a local sanctuary for baboons that cannot live a wild life on the peninsula without putting themselves, other baboons and the public, at risk.

“This will include the many baboons who, in the absence of predators, suffer enormous hardship in old age. Toothless, emaciated and with sparse hair. That is not a humane way to survive a Cape winter.”

Simon’s Town resident Luana Pasanisi uses a red flag to stop traffic so that the Waterfall baboon troop can safely cross the town’s main road.

(Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

Trethowan said there is indeed hair loss among fairly young baboons, as well as older baboons. “Why is this not investigated? Many baboons’ [have] loose teeth — they eat hard substances like pine nuts and mussels and have coped very well through the ages. No one objects to humane euthanasia but it seems some have lost sight of what is genuinely humane and what is population control.”

Oxford disagrees with O’Riain: “The service provider claims the baboons’ teeth are rotten due to sugar and they can no longer feed on natural fynbos. Our oldest baboon died a few years ago, of old age, and she was still feeding on fynbos. Hair loss, we believe, is a direct result of stressful management and range restrictions resulting in suboptimal forage. Our previously unmanaged troop is now managed by HWC and they are already showing scraggy fur and huge weight loss, just within four months. They are definitely losing condition. HWC claims it is due to losing the human-derived food fat layer. The argument fails because since they began house entries and food acquisition have increased. It is stressful.”

- Daily Maverick asked O’Riain several other questions and he gave a lengthy response. It can be read here:

There is another way — a perspective

Dr Ruth Kansky, from the Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology at Stellenbosch University, has researched wildlife tolerance models to understand human-wildlife conflicts and is working on learning-based approaches to improve collaborative human-wildlife governance systems

“There needs to be independent recording of the efficacy of the baboon monitors because you cannot have the service provider monitoring itself,” she said.

“When I was living in Scarborough when HWS [the previous service provider] started the baboon monitoring, I had volunteer residents record baboon presence in the village and compared it to what HWS were reporting. There were discrepancies, which I told them about. After this their reports were more accurate but I could not keep this up long-term because I moved on to other things.

“Another time I was approached by the Baboon Matters Trust to assist them to analyse the raiding and removal of male baboons’ data from HWS’s monthly reports, to see if removing what they recorded as raiding males, reduced raiding by the rest of the troop. The reporting by HWC was problematic, but from what we could gather it seemed like removing specific males did not reduce raiding by the rest of the troop. At any rate, there needs to be a stronger evidence basis for the policy of the City of Cape Town,” she added.

Reflecting on 21 years of baboon management on the Cape Peninsula after her initial involvement in conducting research and setting up the baboon monitoring programme, she described the changes that took place over the years that, in her opinion, led to the current crisis.

- The Baboon Monitor Project continued and expanded to more troops although there were issues of funding, quality and efficacy;

- The Baboon Management Plan that was agreed upon through a stakeholder engagement process was never fully implemented because there was conflict between authorities about their responsibilities;

- The baboon demography changed, with an increase in population and more dispersing males;

- New role players whose understanding and values were different from the original group;

- The authorities became more secretive and less collaborative;

- Management practices were changed without wide consultation and were more intrusive and lethal;

- Conflict arose between stakeholders concerned with animal welfare issues and the authorities; and

- Kataza, who was removed from his group, was “the straw that broke the camel’s back”.

“If I were to pick one key driver it is the value conflict between people with domination wildlife value orientations versus those with mutualistic wildlife value orientations. Domination values are held by people who believe animals are there for human benefit and use and that human wellbeing should be prioritised over animals.

“Research shows that such people support lethal control and other more intrusive management practices. The mutualists’ see animals as having equal rights to humans and support non-lethal and humane management interventions. Scientists and conservationists can also have these value orientations and hence conflict can happen when they have more domination values and some residents and other stakeholders have more mutualistic values.

“One of the more systemic drivers of this conflict and others is that conservation managers are not really trained to deal with people, how to manage conflict or different models of collaborative governance involving stakeholders with different values, worldviews or perspectives. Therefore, when conflict arises they may feel helpless to deal with the situation and prefer less collaboration and take decisions unilaterally.

“Wildlife management in the 21st century should increasingly aim to manage interactions between wildlife and people to achieve goals valued by stakeholders,” said Kansky, quoting from the textbook Human Dimensions of Wildlife Management. DM/OBP

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.