REFLECTION

The Wretched of Life Esidimeni: Inquest reveals necrotic underbelly of an abusive and broken public service

The failure of public servants in the Life Esidimeni fiasco and the failure of the SA Police Service in the Marikana massacre of 2012 echo throughout the South African public service.

Qedani Mahlangu, the former Gauteng MEC for Health, jauntily cited Brazil where she claimed families walked the streets with their mentally vulnerable relatives shackled in chains as a perfectly acceptable scenario for constitutional South Africa.

This was before 144 South Africans perished in extreme circumstances, some from hunger and neglect, in what will eternally be known as the Life Esidimeni scandal — one of the most shocking examples of the violation of human rights in post-apartheid South Africa.

Justice Dikgang Moseneke, who chaired the arbitration in the

matter, said the account was “one of death, torture and disappearance”.

As continuing evidence was aired at the Life Esidimeni inquest this week it was revealed that Mahlangu had, in a meeting in February 2015, also allegedly suggested that “mental healthcare users” released into the care of low-income or poor families could “sleep under a stove”, as Mahlangu claims to have done as a child.

The meeting was attended by department officials and Life Esidimeni management.

The tragedy of the decision in 2015 by the department to “decant” mentally vulnerable people, apart from the dead, led to 44 going “missing”, with 1,418 surviving the ordeal.

On Monday, 30 August, Dr Basuku Mkhatshwa, the former managing director of the Life Esidimeni Group, said that Mahlangu had referred to Brazil in the meeting and in response to concerns raised that poor families would not be able to take care of their relatives.

Advocate Laurance Hodes, representing Mahlangu, was on Monday insistent that the decision to reduce the number of beds for mental health patients was taken by the then minister of health, Aaron Motsoaledi, and not Mahlangu.

The shifting of blame and responsibility has been a feature and a repeated trope by government officials, who also testified at an arbitration hearing that “instructions had come from above”.

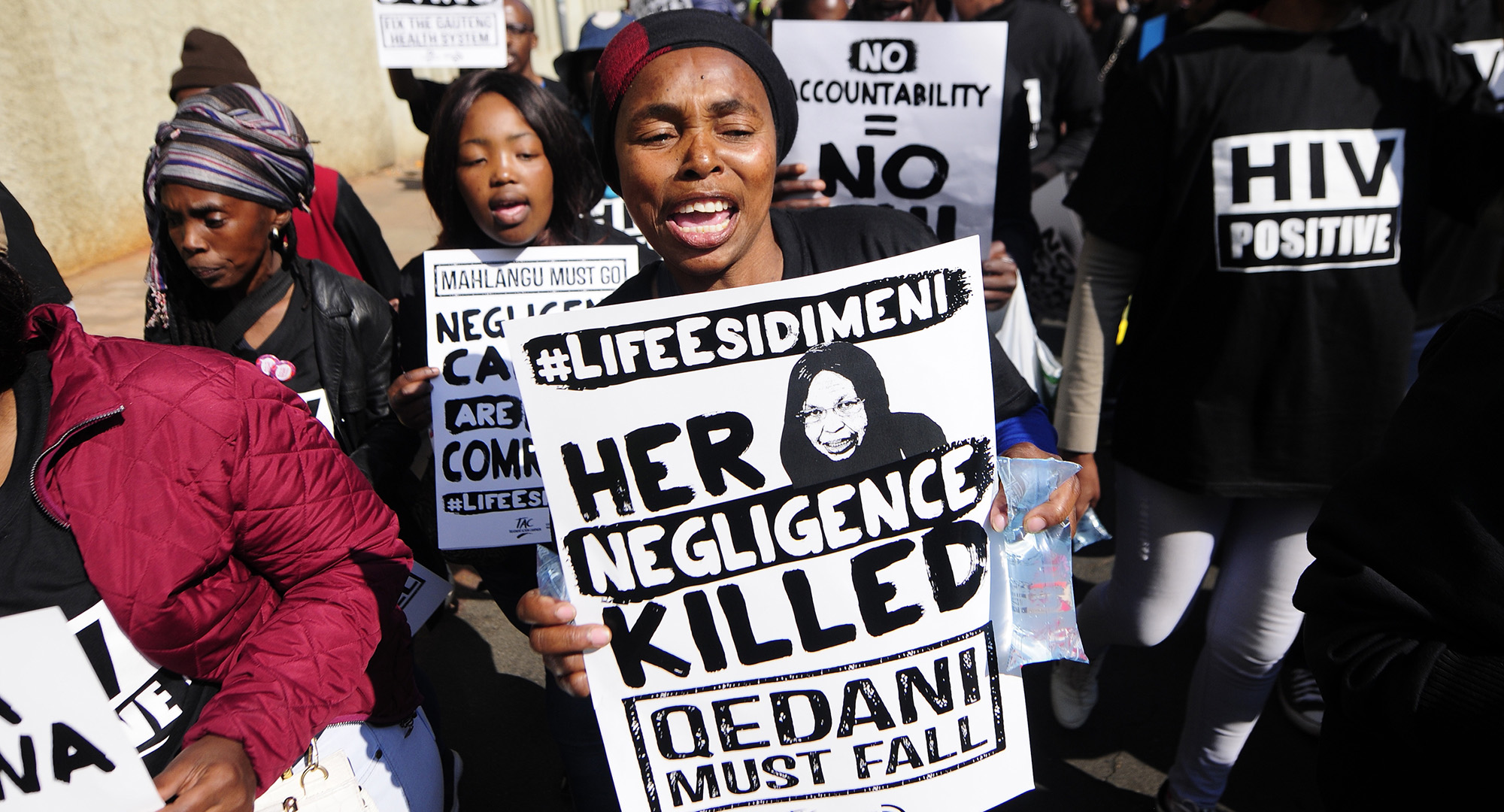

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA ñ AUGUST 07: Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and Corruption Watch activists march to the Gauteng legislature protesting against the re-election of Qedani Mahlangu and Brian Hlongwa into the ANC provincial committee on August 07, 2018, in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Sowetan / Sandile Ndlovu)

Earlier, Makgabo Manamela, the former director of Gauteng mental health, denied that she had had any power to implement or prevent the province’s ambitious Mental Health Marathon Project. The plan had been entirely in the hands of Mahlangu, said Manamela.

She said she had only found out about the plan when the MEC convened the meeting with department officials and Life Esidimeni management in February 2015.

In 2019, delivering the David Sanders Lecture in Public Health and Social Justice, advocate Adila Hassim, lead counsel in the arbitration hearing and who has testified at the inquest, said the only motivation for the department’s plan had been money and how to save it.

In her lecture, she noted that not a single individual in the department had taken responsibility.

“Not one. The officials involved in decision-making were eager to eschew individual accountability, to explain why they could not be held accountable for their own actions. The responsibility, they noted, was collective — belonging to the system as a whole, and in no part to them.”

The inquest this week again heard evidence of how officials attempted to pass the buck when the full extent of the crisis became evident and this after repeated warnings by a group of clinicians, professionals and psychologists.

Civil society too cautioned that the consequences would be devastating, but the department even went as far as misleading the court, noted Hassim, to prevent it from being interdicted.

In the 1990s Brazil undertook a federal reform programme for the country’s mental health users confined to low-quality and often violent institutionalised care to be “decanted” in a similar fashion.

The difference between the Gauteng Department of Health’s vision and that of the Brazilian authorities is that a relatively functional public service in Brazil resulted in the tripling of psychosocial healthcare centre coverage.

Under the Lula administration, the Brazilian government in 2003 enacted the Return Home Programme aimed at “increasing social inclusion” of mentally vulnerable citizens and to humanise treatment.

The underlying principle of reform in Brazil was not money — as it was in the Life Esidimeni nightmare. In fact, 79% of the federal budget, according to the Mental Health Innovation Network, was allocated to community-based services in Brazil.

In the case of Life Esidimeni, more than 1,000 people were forcibly transferred from the private healthcare facility where they were being well cared for and farmed off to unregistered, unlicensed NGOs in Gauteng to be taken care of by unqualified staff.

“The conditions that led to the Life Esidimeni disaster had nothing to do with resources,” Hassim said in her lecture. “It had everything to do with civil servants who did not perform their jobs in a manner consistent with the law, or with the rights of the patients or the families.”

Professor Rossana Maria Seabra Sade, of Brazil’s University Estadual Paulista, writing on that country’s biggest challenge to reform, noted that it was training of staff and officials that mattered most.

In the case of Life Esidimeni, the decision was hastily taken and implemented without thought.

In Brazil most new professionals in the health network were young people “who have not gone through political and ideological struggle process that involved the creation of anti-asylum movement, nor have they lived the intense exchange with emblematic figures of this movement at the international level, such as Basaglia, Foucault, Rotelli, and others, on their visits to Brazil”.

For changes to take effect, noted Sade, “political power” had to be constantly questioned.

As the Italian psychiatrist, Dr Franco Rotelli has written on these reforms, “We believed that this was a technical task, but it was political and one must seek and provoke political power.”

Other issues were present in the Brazilian case, including a review of “the relationship with medicine, with public authorities and with public policies that favour or disfavour the weakest social groups.

“The deinstitutionalisation process lies not in cures, but in emancipation, the creation of new models and opportunities, demystifying the madness, by allowing the exercise of citizenship,” Rotelli said.

The failure of public servants in the Life Esidimeni fiasco and the failure of the SA Police Service in the Marikana massacre of 2012 echo throughout the South African public service where citizens often interact with officials, deployed by the ruling party, and who have little investment in their jobs apart from concentrating on budgets and driving through failed policy.

The inquest continues. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Once again a clear demonstration of the lunacy of appointing inexperienced unprofessional officials lacking the necessary competence to perform their duties. When will they ever learn.

I don’t believe it is that they are inexperienced, they just don’t care about anybody but themselves. Mahlangu has shown absolutely no remorse for this tragedy and I am amazed that teflon Aaron Motsoaledi has escaped censure for his role not only in this but in the total decline in health services countrywide during his tenure as health minister.

I still believe there was a financial motivation for this. Not to save money (never a motivation for the ANC), but perhaps to receive kickbacks from the new shelters that were supposed to look after these patients?

As I understand it, Aaron Motsoaledi is far too arrogant to take advice from anyone and the only way to get on with him is to agree with him. Just witness how he has handled Home Affairs. It just gets worse and worse.

The answer is “they” will never learn because “they”, being ANC appointed officials couldn’t care less. It’s a about getting a salary for doing nothing and doing your best to steal as much as you can.

Qedani Mahlangu, just have a look at her history when being part of the GP government. There was controversy in every position she held. This person should be in jail together with many of her crooked compatriots.

The whole absolutely abhorrent episode another notch in the ANC’s ridiculous ‘ collective responsibility “dodgem- obviously to avoid personal liability- in this , as in many others , since no one person has the guts to take the blame , they should all be arrested and serve if not jail sentences , long terms of relevant community work with hopefully, manual labor involved.

Mahlangu is the very worst of the worst. The dregs at the bottom of the humanity barrel. She makes me ill

No mention of corruption? It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see that there were corrupt payments from unqualified businesses that were contracted to take patients in, to the crooked cadres.

Disgraceful ANC government, which cares not a fig for the people who voted it in. ALL government employees are not interested in the welfare of the citizens, but only in their own self interest. Where will the next Mercedes come from, how can I work the system to benefit myself and my friends and family? You should all hang your heads in shame.

Criminals need criminal justice!

There comes a point in South Africa, at which it is impossible to absorb the extent of the horror that is the public service. When I listen to Ministers bleat on about “our people” it is chillingly evil. Either they have no conscience, no heart, no soul (all of which I suspect is the case), or they are clinically schizophrenic. I know this is a little OTT, but really, everyday speech does not suffice. Money and greed are all they have in common…..