A TOUCH OF VANITY

Sportswear: Decrypting the dress code

With the sports world infested with controversy over clothing, is history repeating itself after it was on a trajectory to liberation?

In the months leading up to the Tokyo Olympics the sports world was ablaze with clothing controversies underpinned by various sports federations’ strict dress codes. Social media was buzzing with criticism of South Africa’s choice of dress which comprised zebra-print jumpsuits and veldskoene sponsored by Mr Price Sport.

Just like a flag, over the years, sportswear has become an ideological marker with a tremendous amount of power and any change can be linked to a change in values and attitudes.

“Flags are not cloths which are silent. It [flags] reflects our values. It reflects our aspirations,” says High Court judge Phineas Mojapelo, interviewed for Netflix-Vox’s Explained Season 3 Episode 3, “Flags”.

Fashion has always been pregnant with symbolism, which is probably why it has been open to heavy politicisation throughout its development. Fashion curator, academic and co-founder of the African Fashion Research Institute (AFRI), Erica de Greef, explains that fashion is a fascinating clue to the social and moral norms of a period because fashion is a social phenomenon with the ability to carry meaning.

“It [fashion] is both ideological or symbolic and material or practical (making and wearing). This dual quality also is both separable from the person – we see it in museums, in magazines, in shops and on other people – as well as an intrinsic part of ourselves and our own bodies. In this regard fashion becomes a powerful tool to create social (and culture) orders as well as the means with which to navigate our place in the world in terms of belonging or in terms of standing out. In other words, fashion straddles the divide that excludes-includes, it marks the boundaries of our being in the world.”

Some of the most famous sporting events in the world, such as the Olympic Games and Grand Slam tennis tournaments, have become as much a spectacle of skill as a sartorial show, where everyone with a stable internet connection or satellite television has a front-row seat.

“Sport itself has become a spectacle, and in so doing sport has become a visual performance as much as a physical feat, and by extension the sportsperson has become aesthetised for visual consumption,” says De Greef.

But just how did we get here?

The birth and development of sportswear

In clothing history, sportswear is a relatively young concept. Did you know that the word “gymnasium” is derived from the word “gymnos” meaning “naked”? About 3,000 years ago, the people of ancient Greece partook in physical activity in the nude. Suffice it to say that this is when and where the initial concept of taking part in professional athletics to demonstrate physical prowess in a designated space was born.

It is strange then that when we fast-forward to the Victorian era when indoor gyms began to crop up – available only to a privileged few with the spare time and money – that the Western idea of sportswear as we know it today, according to a 2016 paper by Mette Bielefeldt Bruun and Michael A Langkjaer for The Journal of Design, Creative Process & the Fashion Industry titled Sportswear: Between Fashion, Innovation and Sustainability, looked exactly like everyday attire and was heavy, stuffy and restrictive.

The Portable Gymnasium: A Manual of Exercises Arranged for Self Instruction in the Use of the Portable Gymnasium by London-based orthopaedic machinist Gustav Ernst, published in 1861, gives us a good idea of the first kind of apparel in which men and women were exercising at the time. Men are pictured in dress trousers, collared shirts, neckties and coats, while women are in hoops, petticoats, corsets, weighty floor-length dresses, long sleeves, collars and pointy, heeled shoes.

According to Netflix-Vox’s Explained Season 2 Episode 4, “Athleisure”, gyms began as private spaces separated by gender which allowed women to wear outfits like bloomers (baggy pants worn as under clothes) that would otherwise have been socially unacceptable if worn in the public eye.

According to Amanda Schweinbenz in her paper, Not Just A Fashion Statement: Bathing Suits, Uniforms, And Sportswear In The Early Olympic Games, women in particular were heavily governed by the social and cultural ideologies of the time, which dictated to a large extent how they dressed and comported themselves.

These ideologies of course applied to exercise as well. In an article by Meredith Mendelsohn for CNN Style updated in July, in the early 1800s, women were categorised as physically incapable and any form of exertion was ultimately associated with disgrace and so acceptable outdoor activities consisted of a dismal choice of strolling or gardening.

Schweinbenz also points out that physicality and competition were used as a yardstick for “manhood” which is why it was seen as inappropriate, if not taboo, for women and girls to participate in physical activity.

Aside from the era’s divisive and exclusionary dress conventions, women’s fashion at the height of the Victorian era was so ill-suited to physical activity that it dissuaded many from taking part in exercise, reinforcing the social comment of the time that exercise and femininity did not go together, explains Schweinbenz.

In a 2011 paper, Sportswear During the Inter-war Years: A Testimony to the Modernisation of French Sport for the International Journal of the History of Sport, Sandrine Jamain-Samson underscores the ideological bottom line of the period: “Elegance, modesty and difference in dress between the sexes were required in most sports.”

According to a 2016 paper by Mette Bielefeldt Bruun and Michael A Langkjaer for The Journal of Design, Creative Process & the Fashion Industry, titled Sportswear: Between Fashion, Innovation and Sustainability, this changed, however, in the first decades of the 20th century, when “sportswear design detached itself from general fashion design due to its practical function and a tendency towards a uniform look clearly distinguishing one sport from another”.

“Aesthetics gradually entered into the picture with colours and patterns used to distinguish players and teams seizing the attention of the spectators,” Bruun and Langkjaer add.

The turn of the 20th century was important to revolutionary developments in women’s sportswear in particular.

The first modern summer Olympic Games were held in Athens in 1896, reborn from the ancient Greek sporting tradition dating back 3,000 years.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was headed by Baron Pierre de Coubertin along with other rich, white aristocrats who supported De Coubertin’s opinions on women’s participation in sport.

De Coubertin expressed on several occasions his belief that the Olympics was no place for a woman, writing in the Revue Olympique: The Development of Female Participation in the Modern Olympic Games, that the idea of women taking part in sport was “the most unaesthetic sight human eyes could contemplate” (sic), according to Schweinbenz.

However, just four years later, in 1900 (a mere 121 years ago), and despite outspoken pushback from De Coubertin and his peers, 11 women competed in the Games held in Paris in a handful of events including lawn tennis and golf, marking their entrance into a white, male-dominated landscape.

French rowing enthusiast Alice Milliat was a female figure who was instrumental in ensuring women’s entrance into the Olympics. With the support of the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF), women’s track and field was introduced as an event at the 1928 Games.

Both Schweinbenz and Jamain-Samson mark the entrance and continued increase of women’s participation in sports as well as the Olympic Games at the start of the 20th century as a crucial turning point in the development not only of sportswear but existing divisive, restrictive and exclusionary dress codes emphasising sexual differences as a whole, challenging conventional attitudes towards “modesty and aesthetics”.

According to Schweinbenz, physical activity became increasingly compulsory in schools and the impact of World War 1 also sparked a change and influenced sportswear as women needed to fill vacancies that fighting men had left behind and their traditional dress proved hazardous to the kind of jobs they filled.

Cue the 1920s – referred to by sport historians as the “Golden Age of Sport” for the marked increase and progression in the accessibility and participation in sport. An increased need for sportswear adaptation and innovation to meet the taxing realities of various sports and improve performance took precedence over social criticism for a while.

“The need for practicality in the field of sportswear relegated aesthetic criteria to second place. Adapting their clothes to the technical demands of individual sports became a necessity for a new generation of sportsmen and women who were looking, above all, for improved performance and sporting success,” Jamain-Samson writes.

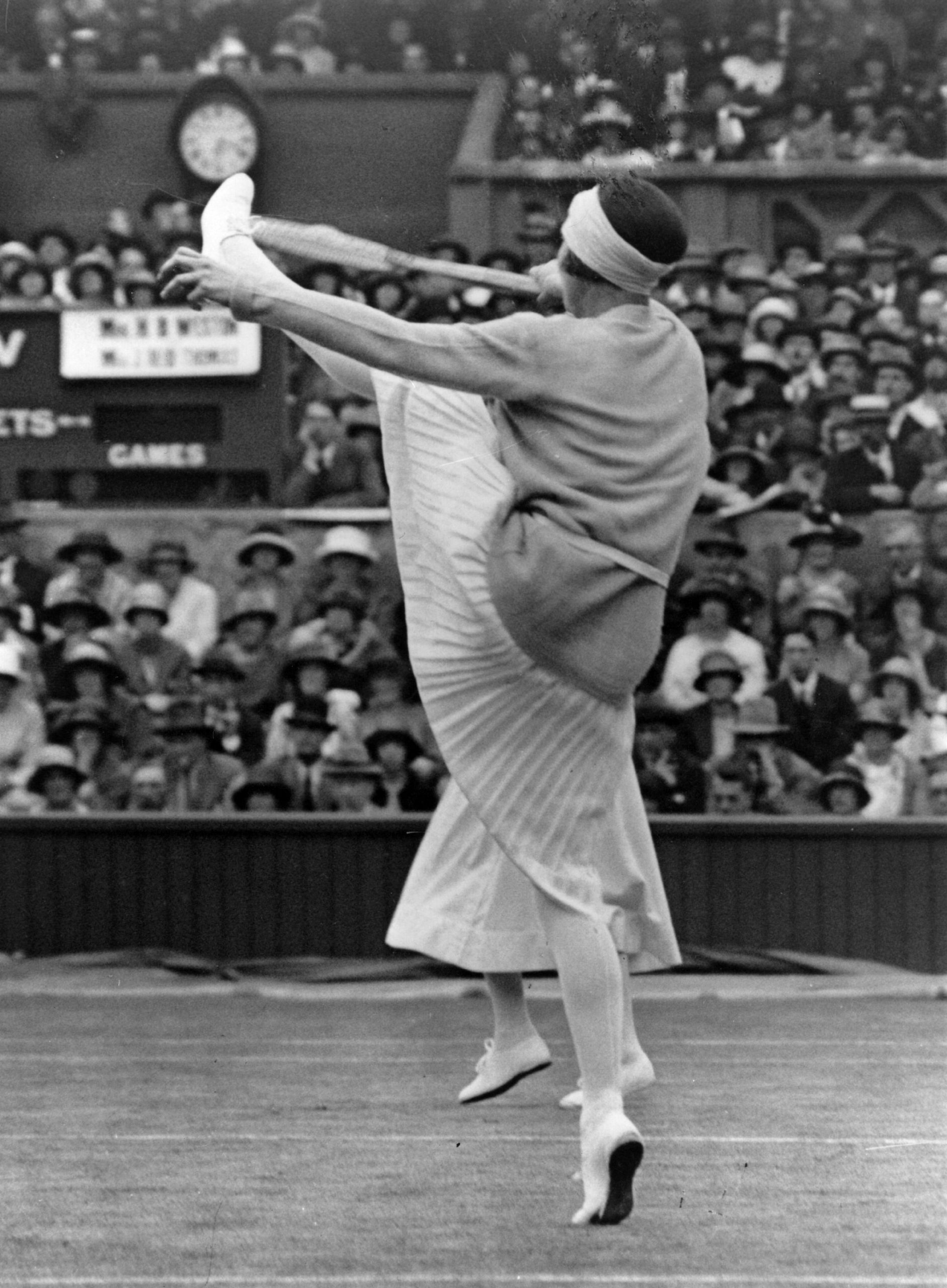

In the 1920s, French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen is pegged as responsible for changing the look of the infamously sartorially strict game. Working closely with French tailor Jean Patou – who together with Coco Chanel made pants fashionable – Lenglen canned the corset, raised the hem of her dresses which were pleated and sleeveless, and swapped heeled, pointed-toe shoes for flat lace-ups.

French tennis champion Suzanne Lenglen (1899 – 1938) high-kicking during a doubles match at the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Championships. (Photo by Kirby/Topical Press/Getty Images)

French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen in action at Wimbledon. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen (1899 – 1938) in play at the Lawn Tennis Championships at Wimbledon, London, 1st July 1919. She won the Women’s Singles title that year. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Lenglen also famously donned a headband on the court, which became her trademark and added yet another dimension of considered styling and aesthetics to the world of sports.

Late Olympic champion Florence Griffith Joyner, aka Flo-Jo, in the 1980s was not only iconic for her skill – holding the 100m world record for 33 years – but also for her characteristic dress style on the track. Coupled with an increase in accessibility to technology and broadcast television, Flo-Jo’s signature look of neon one-legged lycra catsuits and talon-like manicures arguably carried the torch in turning tracks, courts and fields alike into catwalks on fast-forward.

Florence Griffith-Joyner of the United States wearing the hooded speed skating body suit prepares to run in the Women’s 200 metres final event at the 2nd IAAF World Athletics Championships on 3 September 1987 at the Stadio Olimpico Olympic Stadium in Rome, Italy.(Photo by Tony Duffy/Allsport/Getty Images)

Florence Griffith-Joyner runs down the track during the Olympic Trials. (Tony Duffy, Allsport/Getty Images)

Florence Griffith-Joyner shows her medals won at the Olympic Games in Seoul, South Korea. (Tony Duffy, Allsport/Getty Images)

Broader sociocultural and political shifts expedited by film, photos, television shows and books, meant sportswear was on an innovative quest to find clothing that met the technical and exertive demands of sports. Hemlines continued to rise while collars and long sleeves were abandoned to increase and enhance mobility and flexibility and ultimately, performance.

World and Olympic athletics champion Florence Griffith-Joyner of the United States (1959 – 1998) poses for a portrait on 5th April 1988 in Los Angeles, California, United States. (Photo by Tony Duffy/Allsport/Getty Images)

1986: Florence Griffith-Joyner runs down the track. Credit: Tony Duffy /Allsport

Textile innovation

As sports became more specialised so did the need for textile innovation to meet improvements of hygiene, comfort and performance which had a big hand in the evolution of sportswear.

Swimwear, for example, started as long, loose one-piece woolen knitted suits sometimes with shorts or pants attached to the hem of the suit. According to Jamain-Samson, the first notable step in swimwear innovation was a 100% silk competitive swimsuit introduced by Speedo in the 1930s. Experiments with cotton swimsuits were unsuccessful as their heavy-when-wet, slow-drying characteristics made swimmers cold and uncomfortable.

Cyclists soon adopted the silk for cycling shirts for its light-weight wear and ability to hold a tight shape. According to Schweinbenz when women’s gymnastics was introduced as an event in the Olympic Games in 1912, the “uniforms were a short sleeved dress that was mid-calf length, with a rounded collar and synched at the waist. The women wore long stockings and rubber soled shoes without a heel”.

Arguably the ultimate sportswear textile innovation took place in the 1950s with the invention of Lycra or “spandex”. Lycra was a game-changer for sports like swimming, cycling, running and gymnastics owing to its light, elastic, quick-drying characteristics, meaning garments fit closer to the body following its natural form and allowed flexibility and comfort like never before.

While Lycra marked a revolution in textiles and performance, its body-hugging aesthetic and cut led to problems of objectification and sexualisation, particularly of women’s bodies.

Jamain-Samson reports that the simple introduction of “short trousers” into sports attire in the 1920s symbolised a brief moment of the levelling of the sportswear playing field – a progressive feat given the time.

Comparing a photograph of the leading football team of Roubaix Racing Club taken in 1920 with a photograph of the Plymouth Ladies Association Football Team and the 1921 French women’s team, little to no differences in attire can be found.

Jamain-Samson writes: “Their outfits indisputably resembled those of their male counterparts and were a clear demonstration of how aesthetic standards and codes of modesty had changed since the belle époque.”

However, Jamain-Samson furthers that the resemblance between men and women’s football outfits symbolised a threat to the social order of the time and clothing changes were made to establish a clear line between the sexes.

“It was undoubtedly not a coincidence either that clothing adjustments were put forward at the time with the aim of giving the outfit a new touch of femininity – or was it rather to avoid mixing the sexes; deemed to be the cause of uneasiness?” Jamain-Samson adds.

Controversial curveballs

While in theory, uniforms like those for sportswear have the ability to encourage “sameness” and act as a great equaliser, in practice, and through the decades, sportswear quite paradoxically has spurred many instances of exclusion.

De Greef links this paradox to the fact that fashion relies on codes and meanings that are not stable. Back to the analogy of the flag: if you don’t subscribe to the rules and regulations of the moment represented by the sports outfit, you don’t belong.

“What was cool last decade is no longer cool this decade, despite the object remaining the same. It is this instability and ambiguity of meaning that underpins its capacity to both unite and divide,” says De Greef.

Serena Williams of the United States celebrates match point during her women’s singles semi-final match against Anastasija Sevastova of Latvia on Day Eleven of the 2018 US Open at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center on September 6, 2018 in the Flushing neighborhood of the Queens borough of New York City. (Photo by Chris Trotman/Getty Images for USTA)

Creator and co-founder of Johannesburg creative collective The Sartists, Wanda Lephoto’s work has not only questioned insular conventions about blackness in modern society, but also explores and comments on the concept of the uniform.

“Sports in general usually harvest a place for community, a space where different people from different backgrounds can come share their love for a specific thing,” says Lephoto.

“Ultimately the controversy happens when people want to control the outcome of what they would like to see according to what they want and not necessarily what is true and real to the world. It’s people wanting to control how women dress, how much testosterone someone’s body must produce, what your hair can or cannot look like, the idea of looking ‘professional’, all these examples that are in place and are meant to suppress people from truly being themselves,” Lephoto adds.

Bruun and Langkjaer point out that “sportswear is a very sensitive indicator of, and responder to, values. There are the values connected with functional attributes: fit, mobility, comfort, protection; and there are those connected with the expressive attributes: roles, status and self-esteem.”

Schweinbenz echoes Bruun and Langkjaer’s points with a focus on women. “Fashion has always played a role in determining how female athletes experience sport,” she writes.

De Greef weighs in on the potential psychological link between the physical look and feel of the sports uniform and the experience of the sport: “Sportswear is designed to ‘fit’ the body differently – especially with Lycra that ‘hugs’ the body and makes us physiologically aware of our muscles, legs, torso. This embodied experience of clothes, especially sportswear, can have an impact on our relationship to our body.

“Other loose-fitting clothes similarly allow us to move with more ease to swing our arms, perform activities that ‘everyday’ or office clothes do not. Then, there is also the visual relationship that triggers our capacities to run, jump, swim. As the ‘uniform’ signals these actions as both visual memories and physical reminders of our performances.”

Serena Williams celebrates after winning her Women’s Singles fourth round match against Petra Martic of Croatia on day seven of the 2019 US Open at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center on September 01, 2019 in Queens borough of New York City. (Photo by Matthew Stockman/Getty Images)

From denim tennis skirts and black Nike crop tops to leather, studs and gladiator sneakers, for years tennis star Serena Williams’s choice of sportswear has been top talk of the tabloids. Like Flo-Jo, Williams finds power in marrying fashion and her incredible athletic prowess and uses her tennis outfits as a medium for expression and liberation.

“[Clothing is] a tool to empower female athletes, to give them a form of self-expression and individuality in a world that historically belonged to men,” Williams writes in an introductory essay for the catalog, clothing.

Williams gave a nod to Flo-Jo’s revolutionary style in sport in a one-legged spandex bodysuit at the Australian Open earlier this year.

Serena Williams of The United States plays a forehand during the ladies singles third round match against Julia Georges of Germany during day seven of the 2018 French Open at Roland Garros on June 2, 2018 in Paris, France. (Photo by Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

Serena Williams of The United States competes during the ladies singles third round match against Julia Georges of Germany during day seven of the 2018 French Open at Roland Garros on June 2, 2018 in Paris, France. (Photo by Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

At the 2018 French Open, Williams stepped onto the court in a black catsuit. Williams had openly been battling with blood clots and the suit helped with circulation which was later slammed by the French Tennis Federation and banned by the federation’s president, Bernard Giudicelli, from future tournaments.

“I think sometimes we’ve gone too far. It will no longer be accepted. One must respect the game and the place,” Giudicelli told the Associated Press on Williams black bodysuit.

The black catsuit was to inspire postpartum mothers who had been through a difficult pregnancy with Williams tweeting at the time: “Catsuit anyone? For all the moms out there who had a tough recovery from pregnancy – here you go. If I can do it, so can you. Love you all!!”

Serena Williams of the United States returns the ball during her women’s singles semi-final match against Anastasija Sevastova of Latvia on Day Eleven of the 2018 US Open at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center on September 6, 2018 in the Flushing neighborhood of the Queens borough of New York City. (Photo by Al Bello/Getty Images)

Serena Williams (Photo by Al Bello/Getty Images)

Serena Williams (Photo by Al Bello/Getty Images)

Shortly after the French Open, Williams danced onto the courts at the US Open in a lilac tutu designed by American designer and artistic director of Louis Vuitton, Virgil Abloh.

In an interview with Vogue in 2018 she said: “I felt so feminine in the tutu, which is probably my favorite part of it. It really embodies what I always say: that you can be strong and beautiful at the same time.”

Women and people of colour in particular who seem to be at the receiving end of many controversial clothing curveballs still today, continue to challenge blatant racism in sport and reinforce ideas around femininity.

Bruun and Langkjaer note that sportswear can act as a tool for emancipation and “a gesture of defiance”. At the European championships in July, the Norwegian women’s beach handball team was fined €1,500 (nearly R26,000) by the The European Handball Federation (EHF) for failure to comply with the International Handball Federation (IHF) regulations. The team had chosen to play in Lycra shorts over the regulation bikini bottoms which were more in line with what the men’s handball team would wear.

Image: Norwegian Handball Federation

In an interview with CNN, Eskil Berg Andreassen, the Norwegian women’s beach handball team coach, said they were aware of the fine that the chosen attire would incur but that the team had been lobbying for the right to choose what to wear for a while.

“It should be possible to choose – not to say that they have to play like this. If someone wants to play in bikini bottoms, they have the right to choose”, Eskil Berg Andreassen told CNN. The Norwegian Handball Association (NHF) was in support of the team’s decision, tweeting on 20 July: “We are very proud of these girls who during the European Championships raised their voices and announced that ENOUGH IS ENOUGH. We at NHF stand behind and support you. Together we will continue to fight to change the clothing regulations, so that players are allowed to play in the clothes they are comfortable with”.

In a symbolic act, the team competed in their shorts at the Tokyo Olympics.

In gymnastics, an event that has increasingly been spotlighted for sexual abuse, conventional bikini-cut leotards are being swapped for full-leg bodysuits to protest against sexualisation and body policing. Leading the procession at the European Championships in April was the German women’s gymnastics team who appeared in full-length bodysuits to promote comfort and encourage confidence. They too took their full-length bodysuits to the Tokyo Olympics.

The full-length body suit is not against the international gymnastics federation (FIG) regulations. However, the BBC reported that judges had been found to “deduct points when a competitor had tried to make her leotard more comfortable during their performance”.

Other recent examples of blatant exclusionary regulations which spotlights the lack of diversity in elite sport include the banning of burkinis, hijabs and, most recently, the Soul Cap.

The Soul Cap, a swimming cap designed for natural black hair, was banned in July by the International Swimming Federation (FINA).

While the ban is currently on review, in a statement to the BBC, the UK-based brand said its application to include the Soul Cap in the Tokyo Olympics was denied because the cap did not “follow the natural form of the head”.

Co-editor of Sports in Africa, Past and Present and postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Anthropology, University of Johannesburg, Tarminder Kaur says the beach handball and volleyball clothing regulations “are thoroughly sexist”.

“I think women only put up with these as it allowed more visibility for the sport and perhaps helped find sport. Women’s sports chronically suffers from [the lack of] visibility and sponsors. I’m glad that challenges to such regulations are stirring controversy. If they quietly disappeared from the public space that would be a problem,” Kaur says.

Lephoto adds: “The idea that uniforms can’t adapt to suit the current needs and wants for current athletes and performers is also quite regressive. Some of that regression is rooted in patriarchy, racism, sexism and all things that would encourage a space for growth, a space that would encourage people to be free to negotiate the boundaries of their own representation and identities.”

The rule-makers

Jamain-Samson writes that the development of sportswear was not only governed by the physical demands of a particular sport but also sports rules and regulations which are governed and policed by sports federations and committees. While there is a level of practicality and function attached to federations’ dress codes such as varying colours to differentiate teams and represent countries, there is a problem with the second parameter that leaves the question: what are the reasons underpinning many of these dress requirements?

“Rule changes in terms of dress were not restricted to improvements in comfort for sportsmen. The growing importance of spectator sport in society and its role in international relations raised new challenges that had direct implications for sportswear. Attesting to the fact that sport was becoming more of a show, clothes became a new point of reference for all sports performers and spectators, since they identified champions and nations during sporting events,” says Jamain-Samson.

“More often than not, these new demands were defined by strictly visual measures, which were destined to make sports shows easier to follow. In a number of cases, these ‘game rules’ resulted in choices in clothing that were not always compatible with the quest for improved comfort and performance.”

Schweinbenz further states that dress codes are regulated and enforced by different sporting federations, the helms of which have been dominated by white men for decades.

For example, the tradition of wearing all white at Wimbledon dates to Victorian times when wearing white to play sport was purely for “propriety’s sake”, according to Raisa Bruner’s article for Time titled Why Wimbledon Players Have to Wear All White.

Kaur, who was also a tennis coach for eight years, explains that everything from colour to positioning of branding and sports numbers is regulated. “It’s some combination of elitist tradition or culture and commercialisation. Especially televised events like tennis Grand Slams, broadcasters and sponsors also play a role in what gets seen and what can’t be seen on TV.”

Just as women’s attire in the 1800s for sport dissuaded them from taking part in physical activity, the rules and regulations governing sportswear today have been found to not only make these athletes feel uncomfortable when performing, but are discouraging aspiring athletes from sport.

An article published by The Conversation on 5 August, Sexism and sport: why body-baring team uniforms are bad for girls and women, highlights that sportswear codes are based on archaic ideals of Western femininity, which is problematic because “these standards fail to understand that girls quit sport over body-baring uniforms, overlook different hair and skin types, ignore curvy and muscular body shapes and wilfully ignore the realities of periods. What these policies suggest is that women’s bodies are expected to be perfectly thin, perfectly hairless, able-bodied and period-free.”

UCLA’s Katelyn Ohashi competes in floor exercise during a PAC-12 meet against Arizona State at Pauley Pavilion on January 21, 2019 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Katharine Lotze/Getty Images)

An infamous case is that of Katelyn Ohashi, a former American artistic gymnast for the University of California Los Angeles gymnastics team. Ohashi quit the elite sport at the age of 22 partly due to injury but also due to severe body shaming.

“You don’t look like a gymnast”, “You look like you swallowed a pig” were slurs coming from her own coaches, Ohashi recounts in an interview with American talk show host Kristine Leahy.

The rules are cemented in a very Western idea of femininity which is erecting a number of exclusionary hurdles in sports. “Sports apparel codes emphasise social constructs like gender and race,” writes Schweinbenz.

De Greef says that we need to look at who is policing if we want to understand why certain groups of people are still at the receiving end of exclusionary attire and how to clap back.

“The question here is about ‘who is policing’? The answer quite obviously is that (big-money) sport (like media, film, music, literature, the space race) has been primarily dominated by white men. Their capacity to inflict their power is through rules of dress, performance indicators, physical tests and so on,” says De Greef.

UCLA’s Katelyn Ohashi competes in floor exercise during a PAC-12 meet against Arizona State at Pauley Pavilion on January 21, 2019 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Katharine Lotze/Getty Images)

UCLA’s Katelyn Ohashi competes in floor exercise during a PAC-12 meet against Arizona State at Pauley Pavilion on January 21, 2019 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Katharine Lotze/Getty Images)

The Conversation points out that proper, fair representation across a spectrum of backgrounds in key leadership positions is at the heart of change and reform to the current restrictive, biased, exclusionary measures, writing that, “the Olympics should be a place for inclusion, cultural exchange and equality”. This is true for sport as a whole, as De Greef adds: “Fashion – which encompasses sportswear – is just another long-overdue tool of dominance that must be challenged if we envisage a more equal world.”

Lephoto believes sportswear will always be a point of conversation and controversy because different designers design with different outlooks on the world. “Some design with the idea of liberating people and others design with the idea of maintaining the suppression that exists.

“All people should be free to negotiate the boundaries of their own representation no matter how many times that changes.”

Each sport has its own revolutionary sartorial tale constantly testing conventional attitudes towards “sexuality and physical expression”. As Schweinbenz writes: “Change in attire, both subtle and significant, altered women’s sports directly. The increasingly popular Olympic Games became the venue for these new expressions, announcing the arrival of the newly empowered female athlete who cared less about the boundaries imposed by the early leaders of international sport.” DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.