President Cyril Ramaphosa did not disagree when asked if it were reasonable to investigate a link between July’s violence and public disorder and the State Security Agency’s (SSA’s) so-called co-workers — trained, armed but not vetted persons — allocated as a “private SSA security force” to ex-president Jacob Zuma.

“It is a proposition and not unreasonable. And, may I add, it is part of the investigation that is under way because all these things need to be gone into. It’s about the security of the people of our country,” the president responded to evidence leader advocate Paul Pretorius.

Ramaphosa was silent on exactly which investigation he meant.

Chances are it’s a three-strong panel’s critical review, announced as part of the 5 August Cabinet reshuffle that also moved the state security portfolio into the Presidency, as is possible under Section 209(2) of the Constitution.

The panel’s “thorough and critical review of our preparedness and the shortcomings in our response” to the July violence and public disorder was part of the critical measures to strengthen the security services and to prevent a recurrence, according to the president. No timeframes or terms of references have yet been published.

Two of the three panel members are linked to South Africa’s intelligence services; the third, advocate Mojanku Gumbi, was legal adviser to former president Thabo Mbeki.

Chairperson is Professor Sandy Africa, who has written extensively on transformation in intelligence. Perhaps less known is Africa’s time in democratic South Africa’s intelligence structures.

Her University of Pretoria abridged CV simply states “Senior Official: South African government” from January 1995 to January 2007. A little more emerges in the bio in the March 2011 policy paper published by the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces:

“Over a period of twelve years, Africa held several senior appointments in the South African post-apartheid security services. One of these appointments included heading the Intelligence Academy…”, alongside participating in the 1990s as activist and researcher in “the democratic movement’s reconceptualisation of the country’s security philosophy”.

In February 2010 the Mail & Guardian confirmed that Africa, described as “former general manager of the South African Intelligence Academy” and “a progressive voice in the intelligence world”, had been seconded from academia to set up corporate services in the unified state security department.

The other member is Silumko Sokupa, a former Eastern Cape National Intelligence Agency boss, who served as South African Secret Service, or foreign intelligence, deputy director-general before taking over in 2007 as the national coordinator of the statutory National Intelligence Coordinating Committee. He was also part of the 2018 High-Level Review Panel on the SSA.

On Tuesday Ramaphosa told the State Capture Commission one reason for moving the SSA to the Presidency was to get to the bottom of intelligence malfeasance. And that included the SSA’s so-called co-workers, the presidential security force, trained as far back as 2008.

“It is something firmly on my radar screen… including the account of those people, who were given arms, including automatic arms, that have never been accounted for,” said Ramaphosa. “It is part of an intensive investigative process that is under way.”

If the panel must, as Ramaphosa seemed to indicate, investigate this, it would step into a drawn-out probe that was effectively scuppered from inside the SSA.

“All the evidence and documentation was put under lock and key. There was talk of getting a private firm of attorneys to continue,” said Pretorius. “I don’t know why the firm of attorneys rejected that brief.”

In early April News24 reported that law firm Bowmans had pulled out of the probe agreed to a year before.

Pretorius was not quite ready to let go. As far back as the December 2018 High-Level Review Panel report made clear, there had been “serious politicisation and factionalisation of the intelligence community over the past decade or more, based on factions in the ruling party, resulting in an almost complete disregard for the Constitution, policy, legislation and other prescripts…”.

And so the SSA malfeasance and corruption were not just lapses, the evidence leader put to the president.

“These weren’t mistakes. These weren’t slip-ups. Minister [Ayanda] Dlodlo didn’t arrive one morning and say: ‘Oops, I forgot to do this’, or, ‘I made a mistake here.’ This was a deliberate act of misgovernment that possibly has had the most serious consequences for our state.”

That triggered another presidential silence — and deflection.

“All these things are the consequences of deliberate incapability of the state, or State Capture. An accumulation of these are the challenges we face now,” said Ramaphosa before segueing into his glass half-full default position.

“But the fortunate part… is that we’ve got your commission, we’ve got a whole number of other processes that have been embarked upon and have unravelled all these things.”

That response was more than fellow evidence leader advocate Vas Soni got on Wednesday regarding the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (Prasa). The August 2015 Public Protector report, Derailed, put CEO Lucky Montana firmly at the centre of public scandals.

“One of the astonishing things of Mr Montana — and he’s asked for my recusal so I can say what needs to be said — is that in a meeting with [then] president Jacob Zuma, he said the Molefe board was appointed without him being consulted,” said Soni.

“That’s quite frightening. These are the Frankensteins we created. The reason the capture of Prasa flourished, mainly, is by acts of omission. The perpetrators were allowed to get away [with it].”

A presidential silence followed.

The commission chairperson, acting Chief Justice Raymond Zondo, followed up with a question. Why was the Prasa board under Popo Molefe allowed to go when it was “seemingly doing a lot”, and quite well, while SAA board chairperson Dudu Myeni, against whom others had complained, was reappointed?

A presidential giggle, then, “Chairperson, I don’t know if you want me to answer this? It belongs to a chapter with the title ‘The Anomalies of Our Times’. That’s what one can say.”

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Merten-CR-zondo-analysis-potential-inset.jpg)

Molefe and his board were briefing MPs when they were fired in March 2017 by the then transport minister, Dipuo Peters. This was after neither the parliamentary transport committee, nor the then National Assembly Speaker, Baleka Mbete, apparently responded to pleas for assistance.

On Thursday when Ramaphosa was pushed on SSA malfeasance and corruption, which Pretorius described as a security threat, he repeatedly deflected.

“The SSA has a number of quite good people, who want to serve the nation and who want to serve the nation diligently. I will not use a broad brush. I will say quite a lot of malfeasance did happen and SSA was purposed to service political and factional interests by certain of its operatives or officials. Certainly not all.”

That stance echoed the presidential sidestepping of the question of why he has retained ex-state security minister David Mahlobo in his executive as deputy minister, and ex-SSA boss Arthur Fraser as a senior government official heading Correctional Services despite the hard-hitting findings against them.

“Much of what the commission is doing… will be, in my view, the final guide,” said Ramaphosa. “I want to wait for the outcome of the commission. I think that is about all I can say.”

Pretorius pushed back, saying it was a question of whether a person is suitable for appointment.

“Mr Chairperson, I am waiting for the report before I come back to that,” giggled Ramaphosa.

Zondo stepped in to caution that it was almost certain the commission’s findings and recommendations would be challenged. “People will say you can’t do anything; you must wait for the outcome for the review process. Will you wait?”

But Ramaphosa bypassed that also. “Regarding the reviews, that’s from your lips, so I can’t comment on that.”

Over the past two days, it’s become clear the State Capture Commission report will be an important tool for Ramaphosa and his supporters in the governing ANC and the government. The commission’s findings and recommendations would be the neutral assessment that would allow action, for example, against persons under a cloud, while avoiding much, if not all, political factional blowback.

But for now, it’s still being “blindsided”,“ ignoring the signposts” and not seeing the full picture.

It was important for Ramaphosa to emphasise, repeatedly, that staying put in government during the State Capture years, as he had decided, involved “real battles”, some unknown still, to stem the worst. This helped bring about the changes now under way, he said, emphasising that staying put did not impute complicity.

“Were we complicit? The answer is no. Could we be said to be negligent? It could well be, but complicit we were not.”

That, alongside setting an example and using the opportunity to emphasise the extent of change already under way regardless of public impatience was part of the reason why Ramaphosa, as a sitting president, decided to be publicly questioned at the commission.

“Something really wrong happened in our country, and to put it right, I have to go [to the commission] as head of state,” said Ramaphosa. DM

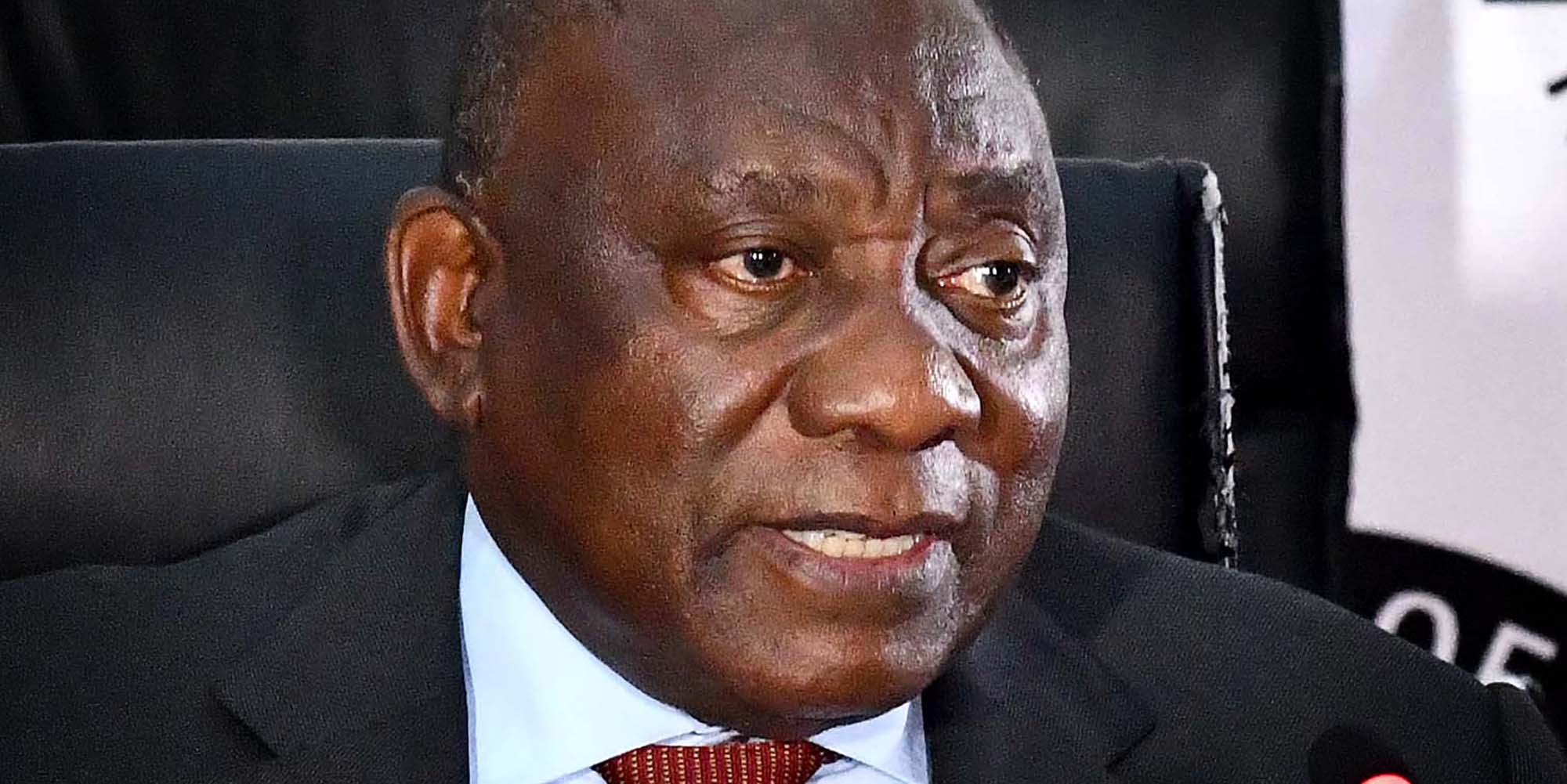

President Cyril Ramaphosa during his second day before the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture in his capacity as the President and former Deputy President of the Republic of South Africa on 12 August 2021. (Photo: GCIS / Elmond Jiyane)

President Cyril Ramaphosa during his second day before the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture in his capacity as the President and former Deputy President of the Republic of South Africa on 12 August 2021. (Photo: GCIS / Elmond Jiyane)