BOOK EXCERPT

Erika Bornman speaks out against the abuse she and others suffered at KwaSizabantu

In 'Mission of Malice', Bornman writes of how KwaSizabantu waged emotional, psychological, and sexual warfare on her, until she finally managed to break free and walk away at the age of 21.

In the 1980s, Erika Bornman’s family joined KwaSizabantu, a Christian mission based in KwaZulu Natal, which is touted as a nirvana, founded on egalitarian values. But something sinister lurked beneath ‘the place where people are helped’

She could not ignore her knowledge of the grievous human-rights abuses being committed at KwaSizabantu, and so she embarked on a quest to expose the atrocities. Bornman chronicles her journey from a fearful young girl to a fierce activist determined to do whatever it takes to save future generations and find personal redemption and self-acceptance.

***

‘Mission of Malice’

January 2000. The start of a new millennium, a new century and a new decade. And the end of my peaceful, anonymous life. Femina’s February issue hits the shelves towards the end of January. It’s a surreal moment, looking at the magazine rack in the supermarket. There’s Jennifer Aniston’s face and, next to her green eyes, on the top right, a cover line: ‘How I escaped a Durban cult’.

The response is immediate. The Natal Witness reports that my article ‘has opened a hornet’s nest, with stories emerging of split families, alleged physical and psychological abuse, excommunications and suggestions of sinister business dealings’.

Aerial view of KwaSizabantu nestled in the Valley of a Thousand Hills – Courtesy of Koos Greeff

In another article, the newspaper says someone else has come forward:

The woman […] related how the mission leader would regularly arrive at the school to shout at the pupils. ‘He would tell us, forcefully and charismatically, that we were from the devil. It was limb-freezing stuff,’ she said in a telephonic interview with the Witness. She described how children were held down by their hands and feet if they screamed during beatings in the hall, while fellow pupils were forced to show no emotion.

There are many more reports in the Witness. And what does KwaSizabantu do? They double down and deny, this time with caveats because, thanks to all the people who have come forward, I’m suddenly no longer a lone voice. Many others confirm the beatings, and so KSB has to change their tune in order to retain any credibility. But first, they have to contend with many more secrets coming to light – stuff I knew nothing about.

A journalist at the Sunday Tribune contacts me. She’d like to investigate, and so we exchange a number of phone calls and emails. In one email, I tell her that I can sum up my experience at the mission, and I believe that of many others, in one word: fear. That is why people have remained silent about the place. I have decided to speak out, not because I have conquered my fear, but in spite of it. I tell her that I wanted my article to be one of hope and encouragement for people still stuck in the destructive behaviour patterns and belief systems imposed on them as children. I felt compelled to speak out – and hopefully something I wrote will help others in similar pain. I know that I was very isolated and unsupported those first few years after leaving the mission, and an article like mine would have been of great encouragement to me back then.

‘Mission of malice’ shouts the headline on the front page of the Sunday Tribune on 6 February 2000. It stretches across the page, huge, bold and impactful. Below the subheading (‘Allegations of military spies in the confessional and of child abuse’), the lead talks of ‘startling allegations linking a controversial Christian mission station with the shady activities of apartheid’s military intelligence structure’.

I had no idea about any of this, but suddenly, those visits from Adriaan Vlok, the then minister of police, start making sense. He’d swoop in by plane – I remember it was an ugly brownish colour, but I guess official military transports aren’t known for their elegance. We would line up to wave at him from the side of the road. There was always proper fanfare when he paid us a visit; we all knew it was an honour to be in this VIP’s presence.

(From the book) Erlo Stegen leads the apartheid government’s minister of law and order Adriaan Vlok on a tour in the late 1980s – Courtesy of Koos Greeff

The article goes on to say that KSB ‘allegedly doubled as an anti-liberation agency for military intelligence and the security branch in the ’80s and early ’90s. Well-placed sources told the Tribune this week that a sophisticated system of information gathering within the KwaSizabantu mission near Greytown is claimed to have led to the kidnapping and arrest of United Democratic Front and ANC activists in northern KwaZulu-Natal. This has been denied by the mission.’

What a can of worms. ‘Information was secretly gathered during “confessions” – a cornerstone of the mission’s religious practice – and allegedly passed on via daily calls on “scramble phones” to Colonel Tobie Vermaak – who worked in military intelligence – and a security branch captain in Greytown, whose identity is known to the Tribune.’

(Vermaak is still at KSB today, by the way. He’s now their head of security. It’s quite fitting that an apartheid security branch operative is still in charge of safeguarding their secrets.)

I’m on more familiar territory on page three of the newspaper. ‘My mission life of fear’ is the heading, and there’s a short synopsis of my story. This time I’m Erika Bornman; I no longer need to be a Joubert.

‘Ex-pupils who contacted the Tribune this week claimed there were cases of excessive violence, in which they were beaten by mission staff until they were bleeding,’ the article continues. Remember, KSB told Femina only a few weeks ago that there had never been public beatings. Now, they concede, a little:

They [KSB] said pupils had been exposed to corporal punishment up until 1994, but this had only been the standard ‘six cuts with a cane’. They confirmed ‘hidings in the upper room’ in which plastic pipes were used on pupils, but this had been carried out by parents, not staff.

They were ‘aware’ that a boy had died after being beaten by his parents on their premises, but they had no specific details. They confirmed virginity testing was carried out at the mission, but only by Zulu parents who wished it.

They admitted excommunication was performed, but denied ever evicting anyone.

Had someone beaten their child to death on my watch, I would absolutely have the specifics. How come they don’t? To listen to KSB tell it, it’s the parents who are doing the beating and the virginity testing – not the school and not the mission.

This is a perfect example of the diabolical semantics KwaSizabantu employs. Yes, the people – mostly but not solely men – who beat the kids are parents in that they have biological children at the school, but they are not the parents of the kids who are beaten. They are school-board members, co-workers at the mission and teachers. Let’s take Michael Ngubane, one of the main perpetrators of the abuse I witnessed. Is Michael a parent? Absolutely. But the public beatings were of children in his care and not his own. Other men I saw beating my fellow pupils were also parents in that they had children themselves. They were, however, not the parents of the pupils they beat.

To claim that it is parents, and not staff, who are abusing these children is not only a gross misrepresentation of the truth, but also an outright lie. Surely, I think to myself, they can’t get away with this. DM/ ML

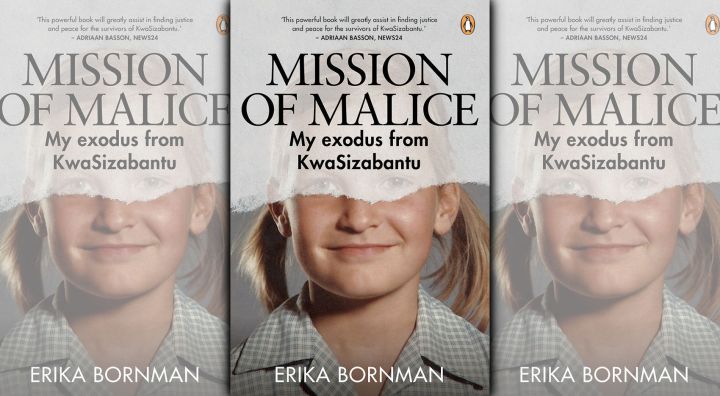

Mission of Malice: My Exodus from KwaSizabantu by Erika Bornman is published by Penguin Random House SA (R250).Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.