NEW FRAME

Textiles carry a living history in ‘Nanima’s Chest’

On its 40th anniversary, the book serves not only as a record of South Asian garments in South Africa, but also of the people who wear them.

This story was first published in New Frame.

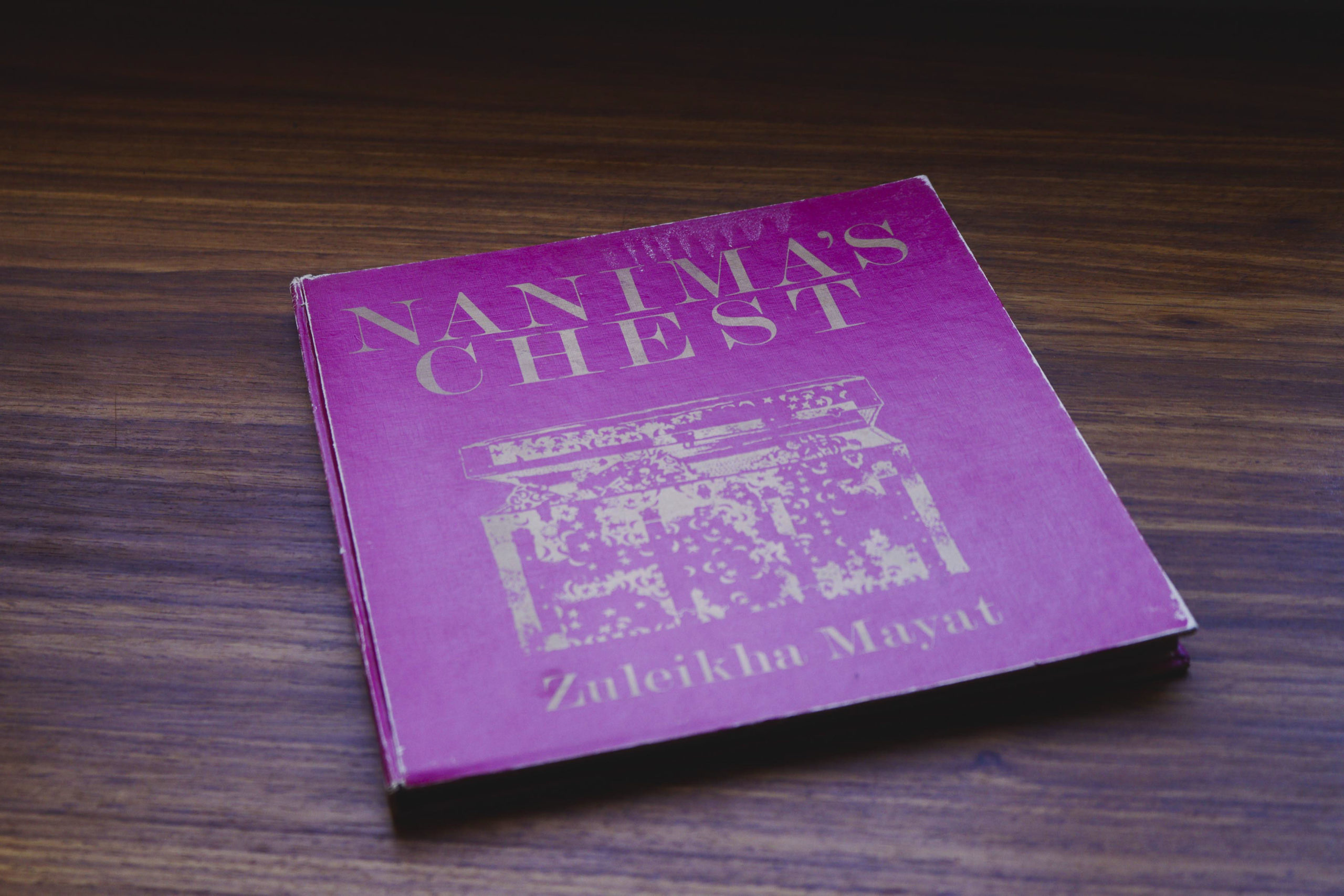

Reading Nanima’s Chest, Zuleikha Mayat’s ode to the textile and fashion histories of western India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, I was introduced to garments and textiles at once familiar and new. Familiar, because some of the textiles referred to in the book lay mothballed in my mother’s ball-and-claw teak chest she inherited from my grandparents. New, because the textile and garment history into which Mayat delves is different to the Tamil one I know.

The book’s title comes from a chest Mayat noticed as a child. This was not her maternal grandmother’s (as nanima may suggest) but her Amina Aunty’s zinc chest, featuring a moon and stars motif. Within that chest, she says, there was “a way of life”, which she sought to preserve and cherish through the book.

Mayat covers a huge chunk of South Asia in Nanima’s Chest – moving from the nomadic Baluch people in Pakistan to Gujarati and Rajasthani dress and textile histories in India. There are sections about Memon garments, with a particular focus on bridalwear such as the cohmby, or wedding veil, made from a fine muslin embroidered with golden thread. Gujarati clothing, such as the sateen or gajee, and the popular gharara, kurta and kameez are also featured.

She probes the history of paisley, looking at the ornate print’s various origin stories. Indians have used the print for centuries, often combining animal and human forms within their designs. Persians believe the print represents the almond leaf, and to Gujaratis and some in the Caribbean, it represents the mango leaf. Scottish mills copied the print in the 19th century, popularising the paisley we know today.

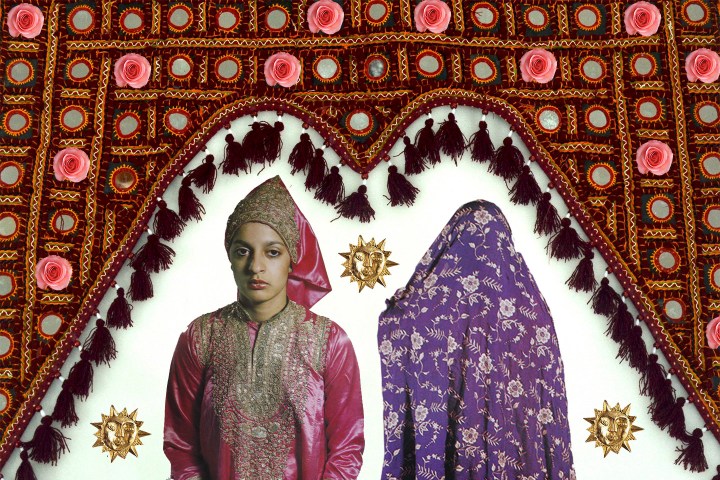

Mayat tells the story of South African Indian identity through fabrics and garments that have travelled across the Indian Ocean during waves of migration from South Asia to South Africa. Collage by Youlendree Appasamy.

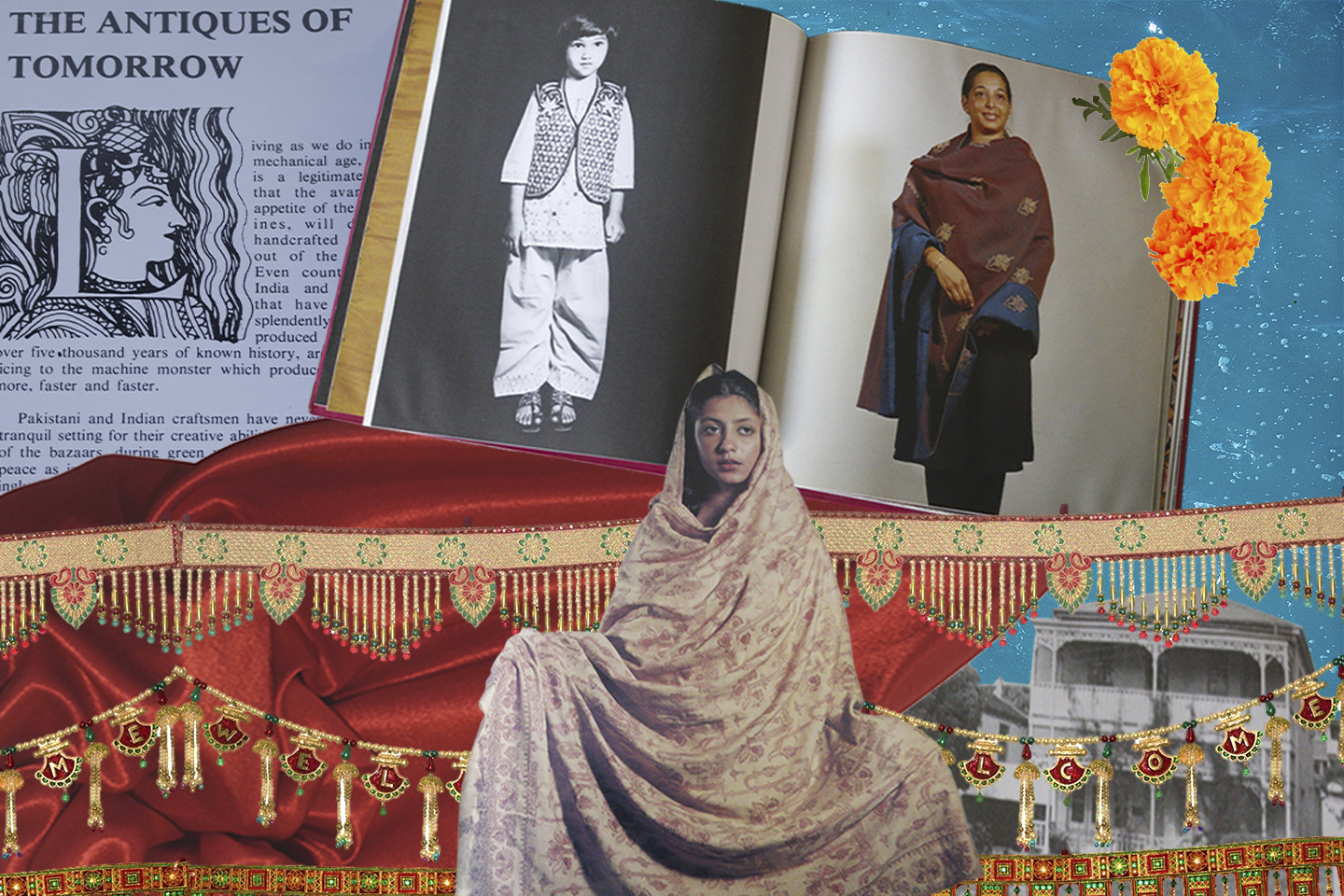

Sepia-toned family photographs from Mayat and her collaborators are woven through the text, providing context for the world in which these garments lived. “Nanima’s Chest is the first catalogue of Indian heirlooms in private homes … This book is important as it makes heritage accessible and in a small way helps break down barriers and counteract the notion that culture can be divided. Emphatically it says that these are ours, for us all to enjoy,” writes artist Andrew Verster in the book’s introduction.

Beyond a catalogue of dress and textiles, the book shows how textiles carry a living history. Culture, as evoked in the book, is active, looking both back and forward. In Nanima’s Chest there is no search for a pure or authentic culture, but reverence for the artistry in creating a bejewelled choli (sari blouse) or tus shawl, so that when fast fashion becomes common place – which is alluded to in the book – and elders die, knowledge about various dress and textiles doesn’t fade away.

Adding to this repository of work is The Odyssey of Crossing Oceans, Mayat’s latest book, which takes the social history of indentured and passenger Indian journeys further. Mayat’s cultural work is not yet done and at 95, she and the Women’s Cultural Group published the book this year. The Odyssey of Crossing Oceans tells the story of the spread of Islam across the Indian Ocean, as well as how trade influenced migrant’s lives, religions, families and traditions in southern Africa, western Arabia and India.

Cultural workers

Riding on the success of Indian Delights, a book on Indian cookery, the Women’s Cultural Group published Nanima’s Chest in 1981. Formed in 1954, the group harnessed the social power of friendships, family relations and informal connections to create a civic organisation.

In Gender, Modernity and Indian Delights, Mayat explains that the formation of the group cultivated and harnessed the talents of the “ordinary housewife, who was sitting at home … They had talent, [but] they didn’t even know what talent they had.” Thembisa Waetjen, co-author of Gender, Modernity and Indian Delights, explains in the book that “members were not merely practitioners, ambassadors and connoisseurs of culture. They were also producers, agents and brokers of culture.”

Their interpretations in Nanima’s Chest demonstrate how processes of migration shaped what certain groups of people in South Africa wear, and in the face of displacement such as the Group Areas Act, the book shows how archiving and personal memory can be made tangible through the tactility of cloth.

Forty years on, Nanima’s Chest serves as an invaluable print record of textiles from western India, Pakistan and Bangladesh found in the homes of Women’s Cultural Group members. Image taken by David Mann.

Composition and class

The items in the book are from members of the Women’s Cultural Group, and the South Asian heirlooms on display and textile histories it invokes largely come out of the group’s composition, their ancestries and class position.

“Many of the founding members were women of a middle-class background, being the daughters, granddaughters or great granddaughters of pioneer Gujarati traders and mostly married to professional or trader-class men of a similar background,” says Goolam Vahed, historical studies associate professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and co-author of Gender, Modernity and Indian Delights.

These traders arrived in South Africa via so-called passenger Indian migration, as well as through the system of indentured labour. Kalpana Hiralal, a historical studies professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, explains the differences in these migrations.

“Indentured labourers arrived as contractual labourers while the latter arrived as free Indians, under normal immigration laws, unencumbered by contractual obligations. Given their differentiated migration status, ‘passenger’ Indians kept close links or ties with their villages as many left their families behind when they initially migrated. However, in the initial period there were strong ties to India from both groups.”

Vahed adds, “We need to dismiss the idea that all indentured migrants were poverty-stricken while passenger Indians were wealthy. Uma Dhupelia Mesthrie, historian from the University of the Western Cape, has shown in her work that the majority of the passengers were working class.”

In Nanima’s Chest, Mayat refers to these journeys of migration and how heirlooms were passed down over time or collected through journeys to India – either undertaken by Indian South Africans visiting family members or by tradespeople visiting the subcontinent.

“These journeys led to the transmission and assimilation of Indian culture, heritage and practices in terms of food, dress, religious practices, cultural practices and more. That heritage still exists today, but it has also to some extent been modified or assimilated within a South African context,” says Hiralal.

Women’s agency in migration and labour

One of those traders was Jari Khala (Gold Aunty) who travelled across the then-Transvaal selling garments and textiles from India. “From dorp to dorp [town to town], she plied her wares. Trousers and dresses, stoles and shawls, waistcoats and fezzes embroidered with silk, gold and silver,” says Mayat.

Jari Khala’s relative freedom to travel as a single, divorced woman hints at a broader history of women within textile and cottage industries – both in rural India and urban South Africa. According to Hiralal, within the patriarchal societies of rural India, women both managed the domestic sphere and engaged in agricultural and subsistence work, which added to the household income.

“This was one of the reasons as to why for example some ‘passenger’ Indian women did not accompany their spouse to Natal. In many instances, they dominated the cottage industries in cotton spinning, weaving and dyeing cloth. Thus, working in the field, taking care of livestock, engaging in domestic subsistence activities were normal activities for women. It was income-generating and an enduring practice in rural India,” says Hiralal.

According to Vahed, in South Africa by the 1950s and 1960s, Indian women joined the labour industry through textile factory work in Durban and Cape Town and replaced many of the white women and women apartheid classified as coloured who constituted the workforce at that time.

“Most of these Indian women were descendants of indentured migrants and under Group Areas, lived in places like Chatsworth and Phoenix,” says Vahed. Many women were active in the trade union movement. They faced a tough job market, poverty and little access to education and literacy, so they entered the textile and canning industries. “These facts challenge the docility of women, as being passive and who had no decision-making powers in the migration process,” says Harilal.

Culture’s evolution

Speaking on the continuities of culture and how Nanima’s Chest fits into the tapestry of the books published by the Women’s Cultural Group, Vahed says, “Indian Delights is not just a collection of recipes, but it has become an artefact because it was a project that reflected progress and modernity on the one hand, with women being educated and being able to read for the first time, but it was also a project of preservation of generations’ culinary knowledge. Nanima’s Chest fits into this stable in terms of attempting to preserve clothing and traditional attires, and more broadly an aspect of north Indian Muslim ‘culture’.”

Culture is expressed in different modalities. Take, for instance, Verulam. Most of the residents in this small, sugarcane town in KwaZulu-Natal do not wear draped banarasi saris every day – you are more likely to find people wearing a knock-off bright blue Adidas tracksuit, or a polyester kurta top with jeans and Puma slides. The garments in Nanima’s Chest don’t fade into irrelevance as a result, but exist as an archive and ode to the people who wore and continue to wear them – perhaps not daily, but as part of the rituals of tradition.

“We are living in a different time, with photos taken and sent via social media globally within minutes. In most cases these photos are deleted as quickly as they are received. The importance of a book in print is that it helps preserve a slice of peoples’ heritage and culture, and can help to transmit knowledge, values and skills from generation to generation,” says Vahed. Traditions evolve over time, and Nanima’s Chest reflects the complex makings of culture on which those of South Asian ancestry in South Africa can reflect, question, critique and ultimately say is ours, for us all to enjoy. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.