Op-ed

Dear Aunti, with Love from Robben Island: Remembering Phyllis Naidoo

The Gandhi Luthuli Documentation Centre at the University of KwaZulu-Natal houses a treasure trove of correspondence between anti-apartheid activist Phyllis Naidoo and a wide network of friends and colleagues. The hundreds of letters, written and received by Naidoo over more than four decades, are potent testament to the contribution of women’s emotional and social labour to the liberation movement.

Annie Devenish is an historian and researcher with an interest in gender, activism and identity in the global South, and how practices of history can and should be harnessed to transform society.

“How can I share your grief at Steve’s death but to say that I wish you great strength… I’d like to walk back and come to you, to hold your hand” writes anti-apartheid activist, lawyer and writer, Phyllis Naidoo to a mutual friend after the death of Steve Biko in detention in September 1977. These words form part of a hidden treasure trove of correspondence spanning more than four decades, tucked away in the Gandhi Luthuli Documentation Centre at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

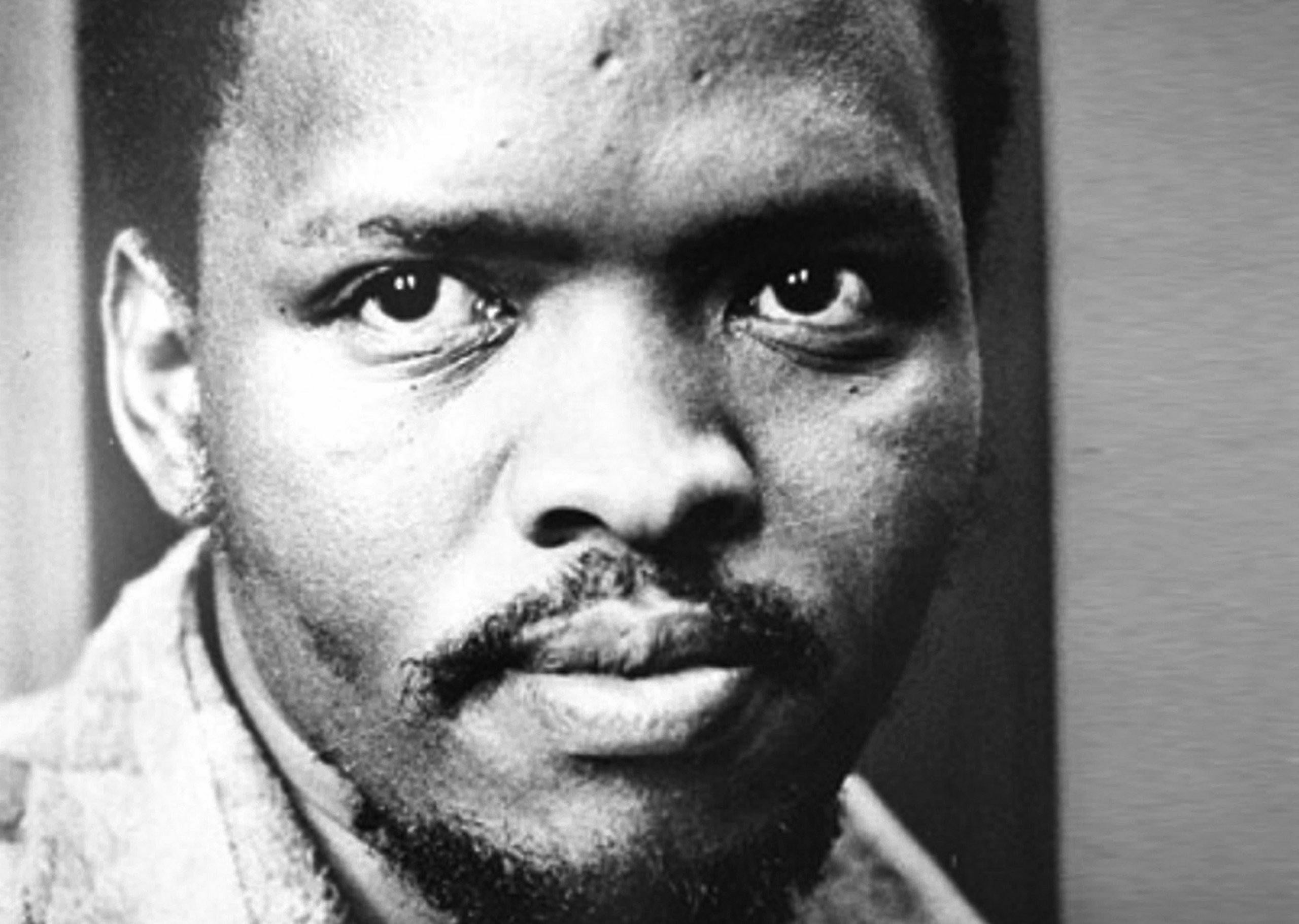

Steve Biko (Photo: biopgraphy.com/Wikipedia)

This collection includes hundreds of letters, both written and received by Naidoo, to imprisoned and detained anti-apartheid activists on Robben Island and their families, as well as friends and colleagues within SA and across the world. Many of these were written during her time under house arrest in Durban, and her 13 years in exile between 1977 and 1990 in Lesotho and Zimbabwe.

Trading in love, solidarity and practical advice, this correspondence reveals the importance of a politics of intimacy, and of the everyday struggle histories. As such they are a powerful reminder of the incalculable yet neglected contribution of women’s emotional and social labour to the liberation movement.

Phyllis Naidoo

Phyllis Naidoo was born on 5 January 1928 in Estcourt, in what was then Natal. Her father, Simon David, was a school teacher, principal and later an Indian school inspector. Her mother, a devout Catholic, stayed at home to look after their large family of 10 children. The family lived in Estcourt, Pietermaritzburg and later Tongaat. Phyllis’s grandfather had been a Tamil speaking indentured Indian and as a child she remembered him going into town to sell the vegetables that he grew in his farm garden.

After completing matric, there wasn’t money for university and so, encouraged by one of her school teachers, she went to work for a charity called Friends of the Sick Association (FOSA), which provided a centre and home for poor Indian TB patients. Soon, however, she became frustrated by the work of FOSA, which she came to see as merely addressing the symptoms of growing poverty and inequality rather than addressing the root causes.

This was a time when Indians in Natal were mobilising politically. In 1946 the Union government passed the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act, restricting Indian franchise and enforcing residential segregation. Many of her FOSA colleagues joined the Indian National Congress-led (NIC) Civil Disobedience Campaign to challenge the Act. It was this growing awareness that led Phyllis to join the Non-European Unity Movement in 1950 which brought her into contact with debates and study groups where she learnT “the mechanics of politics”.

The 1956 Treason Trial spurred her into more direct political action. At the time she was doing a Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Natal in the Non-European section. Responding to the plight of the stranded families of those put on trial, she organised a Human Rights Committee at the University and helped to raise funds for them. This was to be the start of a lifelong commitment to supporting political detainees, prisoners and their families.

Phyllis was also a member of the NIC. This is where she met her second husband, MD Naidoo, who was a member of the South Africa Communist Party (SACP). They were married in 1958 and in 1961 she joined the SACP herself. She began working with other activists to challenge the Bantu Education Act and also began supporting those who had gone underground after the banning of the ANC, SACP and PAC following Sharpeville in March 1960.

Banning and exile

In March 1966 she was banned herself and a year later her husband was charged and sent to Robben Island. Despite these trying circumstances, Phyllis continued to support those in the underground throughout this time. She also studied to become a lawyer. In 1973 she opened the legal practice, AJ Gumede and Phyllis Naidoo, in partnership with Archie Gumede, fellow anti-apartheid activist and lawyer in downtown Durban.

After four years in practice, Phyllis fled across the border into exile in Lesotho. This was in July 1977, following on the heels of the sentencing of the Pietermaritzburg Nine in the Natal Supreme Court in Pietermaritzburg. Phyllis had been part of the legal team involved in defending them during the trial.

Letters as networks of friendship and mutuality

“The terrible heartache of being here is best left untold… in one fell swoop I lost my children (3), my home, my friends and my country,” she wrote to fellow activist Malcolm Smart on 22 August, 1977, from Maseru.

It is in this context of exile, and the isolation and loneliness that accompanies it, that Phyllis turns to letter writing in order to reconstitute an emotional, social and ideological home for herself, her family, comrades and friends, while in exile – a home grounded on networks of friendship and mutuality.

Her American friend in Lesotho, Monroe Gilmour Jr, describes Phyllis as having “an ability to comfort and counsel other victims of apartheid”, stemming from her own experiences of separation, hardship and loss, as wife, mother and anti-apartheid activist.

The accused in the Pietermaritzburg Nine included Harry Gwala and his ANC comrades, all of whom had previous convictions for subversive activities and sabotage and were sentenced to prison terms of seven to 18 years for their terrorist activities. This was a huge blow for their families.

Elda Gwala, the wife of Harry Gwala, wrote to Phyllis in August 1977, “The way I was so happy to receive your letter I even kissed it… We were all shocked about the sentence of the nine accused. I was in bed for a week just thinking of what has happened… I hope you will keep on writing to us and send us some money because you know the condition this side.”

In September Phyllis responds, “Don’t fear we shall all be together again soon… You have to keep strong for all those children at home.”

Trading in love, solidarity and practical advice

For Phyllis, letter writing provided an emotional comfort, but it was equally a way to stay connected to her activism, by tapping into her networks, and drawing on these to provide much needed emotional, logistical and financial support to anti-apartheid activists and their families.

Many of Phyllis’s letters are concerned with organising funds and practical support to detained prisoners and their families. They channel money and instructions to colleagues in the country, to organise transport and permits for families to visit prisoners on Robben Island, and to arrange payment of children’s school fees and for food, clothing, and even birthday presents.

They also offered support to imprisoned and detained activists themselves; sending them letters and cards, arranging permission for them to study in prison, raising the fees for these studies, and ensuring activists had clothes, somewhere to go, and work, once they were released. When George Naicker and Kisten Moonsamy were discharged from prison in Durban in January 1978, Phyllis wrote to fellow comrades to ensure that they were there to receive them and bring clothes for them to wear. “Now George Naicker/Kisten Moonsamy should be in Durban for discharge on 26/2… Organise clothes for Kisten – George should be ok.”

In November 1982 Jacob Zuma wrote to Phyllis Naidoo from Maputo “My dear good sister I[t] was good to receive a note from you… I suppose this will be a surprise to you since you believe that I generally do not write. Perhaps your note is responsible in making me to write this short letter. If that is the case, you must then be a very strong force in a special way to me!” Phyllis was the only person to write to Zuma during his 10 years on Robben Island between 1964 and 1974, sending him an annual Christmas card.

Connecting and raising resources and awareness

During her time in exile Phyllis also maintained a global network of correspondents outside South Africa. This network stretched from Europe (including Germany, Ireland, Norway, and Copenhagen in Denmark) all the way to Australia, and from Florida and the Smoky Mountains in America, to Poona in the Northwest of India, down to Hyderabad and Cochin in the South, then onto Bangladesh, Ethiopia Gambia and Zambia. These networks were important for leveraging much needed resources to support activists and their families within the Struggle, both inside and outside the country, and for spreading awareness of the brutal apartheid regime internationally.

Reaching out across space and time, these letters are a powerful reminder of the abundant and selfless emotional labour that women invested in the anti-apartheid struggle. They show how personal relationships and friendships underpinned and sustained political activism in the public sphere, and in so doing, call for a complete reorientation of the way we write “political” history. While it is fitting that South Africa’s Women’s Day on 9 August remembers and celebrates the public face of women’s activism with the 20,000-strong Women’s March to the Union buildings in 1956, it is equally important that we begin to unearth and recognise these hidden contributions. DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thanks Annie for providing an insight into the courageous and unique life of Phyllis Naidoo.