BUSINESS MAVERICK ANALYSIS

Global trade fortunes diverge, but China’s share of the pie has proved surprisingly sticky

If there’s one thing the pandemic has taught us, it’s to expect the unexpected. This is no truer than in the trade world, where China has gained market share notwithstanding its progressive decoupling from the US. SA trade continues to ride high as advanced economies move further into deficit.

Current account balances are a good temperature gauge of external, inter-country economic dynamics — and there have been some unexpected shifts during the pandemic. Some of these belie seismic geopolitical developments and are not an accurate reflection of different countries’ relative economic performance.

Most surprising is the headway China has gained in the trade realm, particularly among advanced economies, including the US, when US-Chinese decoupling is, to all intents and purposes, already under way.

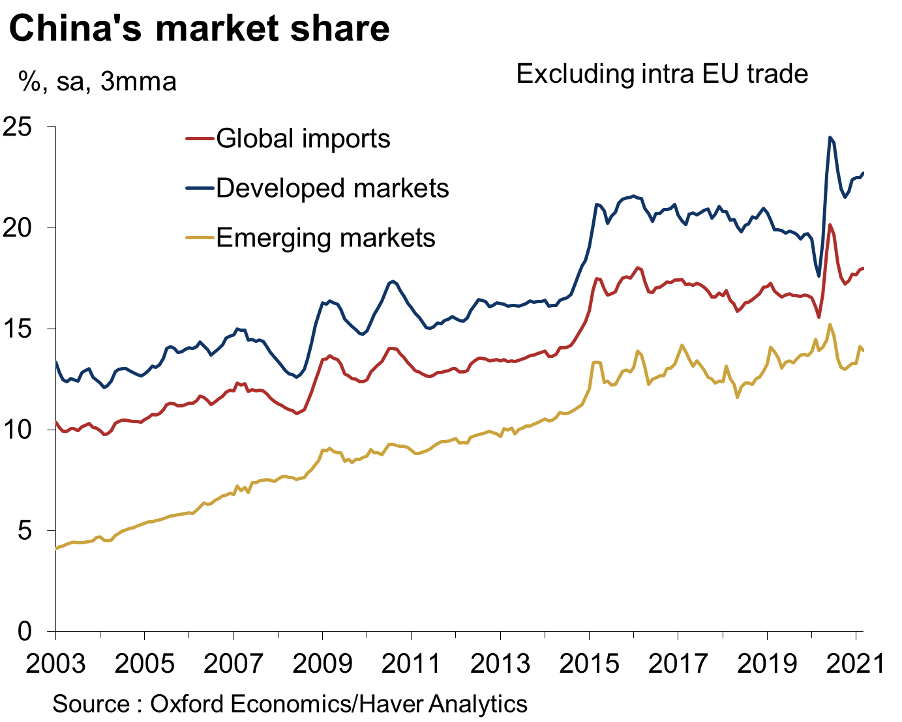

Recent research by Oxford Economics finds that China’s global market share has grown considerably to 18% over the past couple of years and that it has made the most significant trade gains in market shares in developed versus emerging markets.

According to the consultancy, China’s market share gains in developed countries “were triggered in part by the nature of the recent increase in demand for imports in the developed world, which was fuelled by a (temporary) shift from services consumption to goods consumption and a surge in work-from-home (WFH) demand”.

Despite Donald Trump’s call to decouple the US economy, the trade war in 2018 and an urgent desire to reshore supply chains, China’s exports to advanced economies have grown considerably over the past year and a half, as shown in the graph below. Emerging markets have not shown similar import demand for Chinese products.

According to Oxford Economics: “China’s strong export performance since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic underscores that the global supply chains developed in recent decades — and in which China plays a key role — are much “stickier” than many suspected.”

Given how significantly the US and China have upped the ante over the past few weeks, it’s highly debatable how sticky these will remain in the years to come.

Also released this week, the IMF 2021 External Sector Report reveals some fascinating underlying shifts in external trade and current accounts during the pandemic. Based on its research, the IMF calculates that the global current account balance increased in 2020 to 3.2% of GDP from 2.8% the year before and it is expected to widen further in 2021.

Most notable is how uneven the impact of the crisis has been across countries, with the US, France, UK and Canada found to have lower current account balances than warranted and Germany, the Netherlands, Mexico, Poland and Russia larger balances than warranted.

Fiscal spending programmes as well as other pandemic-related trends, like spending on travel, oil, medical goods and household consumption goods sectors are driving the divergence in countries’ current account fortunes, according to the research.

Says the IMF: “Despite the global recovery in merchandise trade, spending on services remains subdued, with global tourism arrivals far below their 2019 levels and sharp falls in trade balances for tourism-exporting economies.

“Oil exporters also initially saw sharply falling trade balances, but these gradually recovered after mid-2020 with rising oil prices. The lockdown-induced shift in household spending from services to consumer goods and the health-emergency-induced trade in medical products have triggered further movements in exports and imports.”

Meanwhile, in South Africa, bumper trade data in June highlighted that the country’s trade fortunes just seem to get better and better — and are likely to continue doing so until internal consumer demand for foreign goods regains momentum and begins to narrow the handsome trade surplus.

When that happens, South Africa will no longer be able to rely on bumper export receipts to bolster an economy already buckling from the looting and supply-side issues brought on at the start of the third quarter of the year.

But are these trends likely to continue?

South Africa’s widening trade surplus to a large degree relies on sustained high commodity prices, which may not continue to be the case if the Delta variant of the virus stalls economic recoveries around the world and undermines the consumer demand that is propelling most commodity prices to new levels.

Absa economist Peter Worthington sees the current account in Q2 and for 2021 as coming in at 8% of GDP (versus 6% previously) in quarter two and 4.7% in 2021 versus his previous expectation of 4.2%. He notes that if the second quarter comes in at his anticipated level, it will be the highest current account surplus “in democratic South Africa’s history”. His forecasts do factor in the short-term uncertainty introduced by the recent unrest in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng and the fact that the Durban port was not able to operate for some time.

The IMF expects South Africa’s current account balances, as well as those in India, Indonesia, Mexico and Poland to decline “as domestic demand recovers under current policies”.

For the rest of the world, the IMF projects that the US will see a current account deficit of 3.7% of GDP in 2021 versus the previous year’s 2.2% as a result of the country’s fiscal expansion outpacing higher private sector savings. It expects this deficit to start declining in 2023 to below 3%. In the euro area, the surplus is expected to increase by almost a percentage point to 2.8% of GDP this year and remain there for the medium term.

China’s current account surplus is forecast to contract by 0.2 percentage points to 1.6% in 2021, “as the effects of the decline in outbound travel, lower commodity prices, and a surge in pandemic-related exports wane, and converge toward about 0.5 percent of GDP over the medium term, with continued rebalancing toward consumption driven growth”.

All these shifts are not significant enough to change the picture of a world in which divergence is both the economic and trade watchword. Instead of these extremes balancing out, however, the very real prospect of a complete decoupling between the two superpowers, the US and China, promises further shifts from any state we may have experienced before. DM/BM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.