MAVERICK CITIZEN 168

Chris Hani Baragwanath hospital’s superheroes: Saving lives on the Covid-19 frontlines

Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital has come through a Covid-19 war and an insurrection. The frontline Gauteng hospital of a raging pandemic and a violent looting spree has dealt with overwhelming sickness and trauma. It has cared for the greatest number of cases of any hospital in South Africa. Nobody has been turned away. Many lives have been lost, but many have been saved, in large measure, thanks to health workers who have shown up despite massive challenges.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

This week I had the privilege of interviewing several of the doctors who have been leaders on the frontlines during an almost unprecedented level of demand for emergency services at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital. In the midst of their frenetic rounds I spoke to Dr Kavita Makan, the team leader of the hospital’s Covid-19 response, Dr Riaan Pretorius, the acting head of the trauma unit, and Dr Rachel Moore, head of the acute care surgery unit.

I asked them about how they had responded to three successive waves of Covid-19 and the recent spate of violence following the looting. These are their stories.

Chris Hani Baragwanath guards the entrance to Soweto, a city of more than 1.8 million people. It is famed as the largest hospital in the southern hemisphere, its campus the size of a small town. It has more than 2,800 beds and 6,700 staff. It stands to reason that during a pandemic, a giant hospital is going to have an even larger role to play in protecting life and health.

But, unfortunately, because of our history, Chris Hani Baragwanath’s mission has never just been to attend to victims of bugs and viruses. Going back to the days of apartheid, it has also had to deal with the oil spills of police violence, poverty and inequality. It has always been on call. But in the last year the demand has been unprecedented. Most recently, during the peak of the Covid-19 third wave in Gauteng, it was on the receiving end of both Covid-19 and the recent looting and violence.

But this didn’t deter those who work there.

According to Moore, despite the fact that the violence was literally on Bara’s doorstep, “people continued to come in to work across the board. Instead of staying at home, WhatsApp groups were buzzing, relaying reports on safety and alternative routes to work. It was difficult for nurses who lived in violence-wracked areas and couldn’t get taxis, but almost everyone who had their own transport came to work.”

This level of public service is testimony to the fact that those who work at Chris Hani Baragwanath know they are the guardians of life and death for millions of people living in its large catchment area.

The hospital can’t afford to seize, stop or fail. Yet, despite this, public hospitals and the people who work in them are often taken for granted. There is little knowledge of (and sadly interest in) what CHBAH does, or who does it, to fulfil its constitutional responsibility to ensure access to healthcare services.

Hopefully these interviews will help change that.

Dr Kavita Makan is a rheumatologist who has worked at Chris Hani Baragwanath since 2014. It is no exaggeration to say that Covid-19 changed her career and her life.

In July last year, her colleagues chose her to be the team leader of the hospital’s multidisciplinary response to Covid-19. She rose to the responsibility enthusiastically, but with little idea of just how big a challenge it would be.

On the day I spoke to her she was obviously exhausted. She had been on call for a week and said she was “physically and emotionally spent”. But behind her tiredness there was a quiet sense of accomplishment.

Our interview, she said, was almost the first time she had had to reflect on what they had just been through.

It was mixed with a feeling of disbelief.

“Because of the hospital’s size we dealt with the greatest number of Covid cases of any hospital in the country. It was an onslaught. People worked tirelessly, nonstop, with their heads down. Doctors, nurses and auxiliary staff worked beyond expectations.”

Of the more than 2,800 Chris Hani Baragwanath beds, she told me that internal medicine takes up close to 1,000 of them. At the peak of each wave of Covid-10, 400 to 500 beds were occupied by people with Covid-19. “We never stopped taking patients. We prioritised helping as many people as we could.”

Makan sounds happy to have the chance to talk about health workers, who are the “unsung heroes” of the Covid-19 response. She is at pains to stress that it was unprecedented teamwork that carried the hospital through three tsunami-like waves of Covid-19.

I ask her how they managed and she tells of how, early in the pandemic, when little was known about SARS-CoV-2, the internal medicine department put together a multidisciplinary team, made up of all the different disciplines of internal medicine, because managing Covid-19 would have an impact on them all. The team included cardiology, rheumatology, infectious diseases and haematology.

It was mainly made up of younger staff, like herself, because of the need to shield older staff who were known to be more vulnerable to severe Covid-19 disease. Then, “my name was put forward by my colleagues to lead the team”, and that’s what she has been doing ever since July last year.

The team was a big one – more than 60 doctors and 100 nurses – but, even so, “patient numbers were well beyond the staff available”.

Makan recalls how each wave of Covid-19 (there have been three: June to July 2020; November 2020 to February 2021; and June to July 2021) was distinctly different and required a different response.

In the first wave the team learnt by doing, by trial and error.

“To begin with, there was a lot of fear; there were challenges with PPE [personal protective equipment]; there was the challenge of integrating teams and working together. There was double, then triple the workload and we were psychologically hit very hard. But this was when we prepared and planned and developed important strategies that carried us through the epidemic.”

By the second wave they were more comfortable: “Although the numbers were higher than wave one, it felt easier; we understood the disease, we were able to innovate and learn, had the benefit of a donation of Tocilizumab [an expensive monoclonal antibody therapy that helped improve recovery time in patients with severe Covid-19]; we were able to use CPAP [continuous positive airway pressure] devices and some high flow nasal oxygen [HFNO].”

But the third wave came like a punch to the solar plexus.

“We were unprepared,” Makan says. “We went from 100 to 400 Covid beds in two weeks. We had to take over surgical areas and eventually the team worked to activate 180 beds in the new ABT [Alternative Build Technology] facility. The closure of Charlotte Maxeke [hospital] made it worse, and then the rioting was the last straw.

“Every day was a new drama. It was the most gruelling and demanding… People were pushed to their limits. We had to wear hats we never thought we would. I became an engineer, a planner and a manager – it almost made clinical medicine the easy part.”

“We had many hard days, but just as many successes. Seeing someone who was critically ill walk out is the greatest feeling of accomplishment.”

Once more, it was teamwork that pulled them through: “I met and worked with extraordinary people; I’ve seen leadership and depth in so many people, junior and senior staff alike.”

One of the miracles that has taken place at Chris Hani Baragwanath is that the hospital didn’t collapse under the weight of Covid-19. To the best of their abilities and energies, health workers ensured that other crucial health services continued.

Dr Riaan Pretorius is a man who doesn’t waste many words. He’s been a trauma surgeon at Chris Hani Baragwanath since he qualified a decade ago. When we spoke he wasn’t much interested in talking about himself. Instead he was straight to the point.

“On Sunday [11 July] when the violence started, initially Helen Joseph Hospital bore the brunt. This was because the violence had started in the inner city. However, Helen Joseph was soon overwhelmed and by Monday it hit CHB with full force.”

Resuscitation is the medical term for “any injury that is critical” and must be managed as quickly as possible.

Chris Hani Baragwanath’s trauma unit is never quiet. On a “normal” weekday it will do eight to 15 resuscitations. On the weekends, that figure rises to 25 a day. On 11 July, the emergency department saw 115 people in 12 hours; and the doctors in the trauma unit carried out 46 resuscitations – 34 of the resuscitations were necessitated by gunshot wounds. Nine people had to be taken for laparotomies, a type of open surgery of the abdomen to examine the abdominal organs. Two people were dead on arrival.

Day two of the looting was not much quieter: “down” to 38. On day three, 13 July, it was 20 and by 15 July, says Pretorius, they were back to “normal”. But, during those three days, “the team were working 24/7, sometimes with four operating teams working at the same time”.

They had to call in extra support and reclaim surgical beds that weeks before they had “sacrificed” to the Covid-19 ward. According to Pretorius, “it was overwhelming. It felt like what we get on our busiest days in December when many people are fuelled with alcohol.”

Pretorius and other colleagues were surprised at the number of wounds from gunshots: most came from handguns, but some were from rubber bullets used by the police.

Another senior doctor told me that in one case a rubber bullet with its casing intact was found lodged in a person’s abdomen, “suggesting that it had been fired at point blank range”.

Pretorius doesn’t need to embellish or exaggerate. He seems to have come to terms with South Africa’s pathologies of violence.

“In South Africa people don’t respect life; they don’t expect consequences; there’s no accountability.”

He thinks “there must be some underlying anger in our country that gives South Africans a unique psychological profile. In lots of countries people get drunk, but they don’t shoot each other.”

In addition, poverty brings with it its own risks. In winter, for example, a common cause of trauma is burns as people try to heat shacks and homes. “That hasn’t stopped.”

But, he adds, in recent years “things have got worse” noting that nyaope [a street drug] addiction is a major factor, with the trauma unit often having to resuscitate “nyaope boys, who have been badly assaulted by the community”.

On the other side of the corridor from the trauma unit is the acute care surgical unit. At the height of the third wave, however, the two units shared the same space in order to make extra space available to accommodate the overflow of Covid-19 patients.

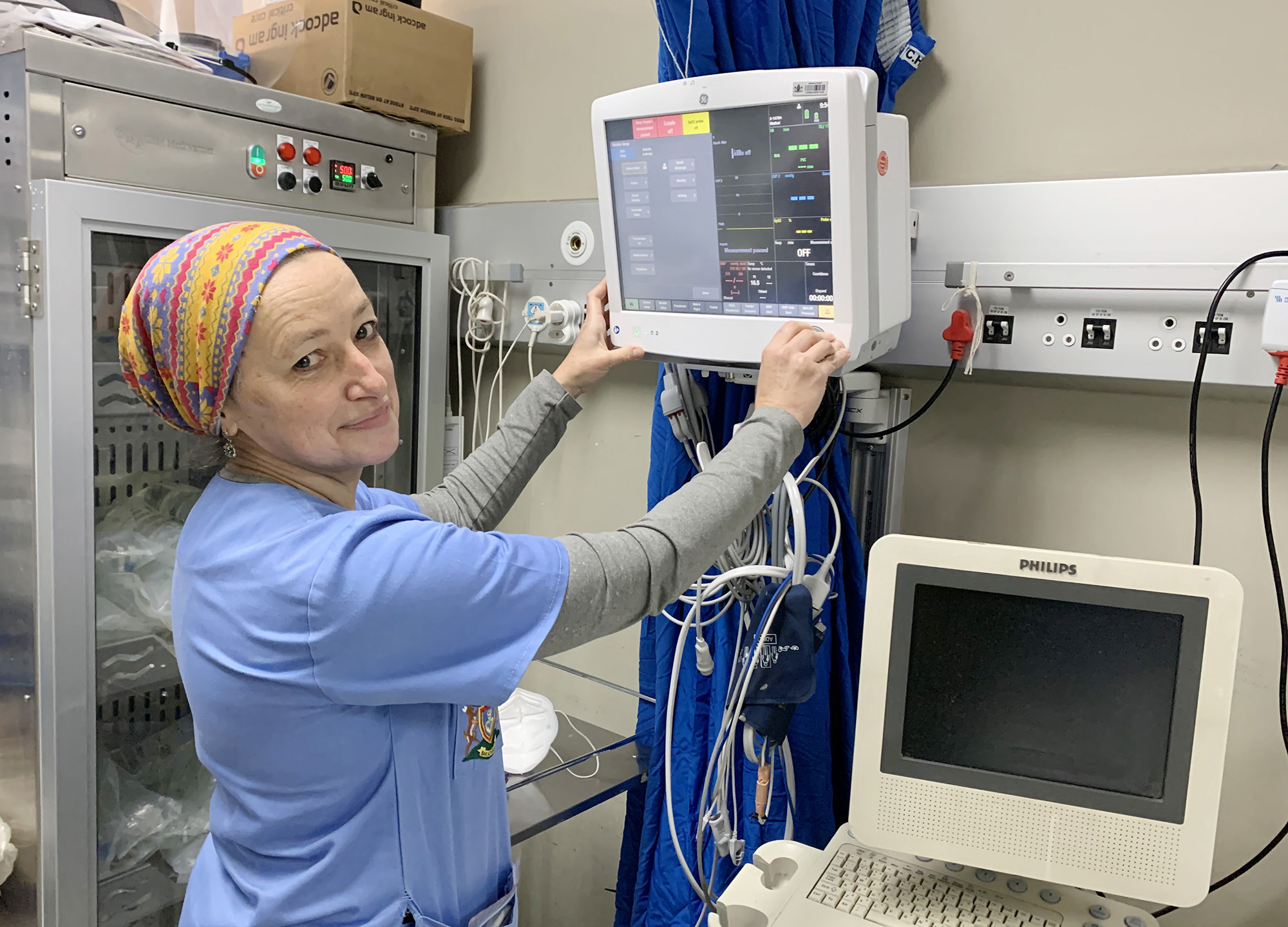

Dr Rachel Moore, the head of acute surgery at Chris Hani Baragwanath hospital. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

The head of acute surgical care is Dr Rachel Moore, a specialist general surgeon who, with close to 10 years at Chris Hani Baragwanath, is a veteran of another sort. Moore explains the relationship between the two units simply: “We handle the non-trauma surgical emergencies.” These are emergencies that are life-threatening but disease-related, such as ruptured appendices, diabetic feet and late-presentation cancers.

Their unit may not have been the frontline for the shooting and assault victims, but there is a symbiotic relationship between trauma and acute surgery, and the pathologies of pain that afflict the outside world.

“When trauma is up, we are quieter. Last week my unit’s numbers were down and have been throughout the recent Level 4 lockdown that started on 28 June.”

That’s because it’s more difficult to get to the hospital. But there’s a sting in the tail.

Moore explains that after the lockdown ends “we get a health backlash”, what she terms “the collateral damage of the pandemic, people who should have come earlier and now present as desperately unwell. This is the unseen side of the pandemic.”

She calls it “the non-Covid Covid-related fallout”.

“We always had a problem with people presenting later with serious illnesses than in the rest of the world, but now it’s even worse. We are seeing young people die of appendicitis… It seems unfathomable but it’s easy to understand. There are late presentations of cancers and a ridiculous number of melanomas … feet you can’t salvage. A 32-year-old died last week due to a neglected abscess.”

Moore notes that although the damage Covid-19 has caused to the management of communicable diseases such as HIV and TB is appreciated, the same recognition is not yet given to other medical and surgical emergencies. Like Pretorius, she is well aware of changing patterns in healthcare caused by the waves of Covid-19 and the social consequences of each successive lockdown. But something that should be of great concern to health planners is Moore’s description of how, from October 2020 onwards, the acute surgery unit has seen their load “plateauing at a higher level than previously; there has been a sustained increase in numbers”.

She thinks this is because of financial hardship: people losing jobs and their medical aids. In addition, the late presentation of disease means longer stays in hospital and intensive care, thus increasing costs.

As she tells me this, I wonder to myself why the Department of Health didn’t – and seemingly can’t – anticipate these challenges. Why doesn’t it learn lessons and why is its response always reactive?

In the face of a debilitating dysfunctionality in the Gauteng health department, it seems that the clinicians in our hospitals have to become planners, coordinators and carers all rolled into one. From my observations at Chris Hani Baragwanath and other hospitals, there is very little engagement between bureaucrats and the worker bees on the ground. Neither is there much understanding of what their colleagues are going through.

But Moore stays clear of politics in our interview and I don’t put these thoughts to her. Yet her answers seem to confirm my suspicions. When I ask how health workers cope under these conditions, she brightens up and talks about the “magnificent cooperation of the Covid response at Chris Hani Baragwanath”.

She says that internal medicine – “amazing colleagues” – are the frontline, “but they don’t have enough staff so we all pulled together. We assess wave by wave, and the response is clinician-driven.

“Clinicians always make a plan!”

Caring for the carers

I round up the interviews by trying to understand how health workers are coping with stress and exhaustion. Apart from their roles as doctors, they are still mothers, fathers, husbands, wives. Makan, for example, has a nearly four-year-old son.

Moore says that the first wave was “very, very hard”. The second wave was easier because they had learnt more about Covid-19 and could plan to meet it. The third wave, she says, “has been very difficult due to factors beyond Covid – the three-month closure of Charlotte Maxeke hospital and now the violence and looting”.

She commends the psychology and psychiatry units at Chris Hani Baragwanath for putting in place a care system for the hospital’s staff. But, she says, most health workers “put their head down, no matter how intense [the work]”.

After being witness to so much death and loss, Moore thinks that “if you stop and introspect and allow for the horror to register, then the unspoken fear is that you will collapse and that it will impact on your functionality”. She knows “it’s not healthy” and thinks “we will see a wave of PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] at some point”.

Makan’s response is similar. But what strikes me is a level of empathy and understanding of her colleagues that I am sure they felt too, and which accounts for their trust in her as their team leader.

“When you are in the midst of the crisis you don’t take stock.

“It’s only when you are in the trough that you acknowledge what you just went through. At the end of the first wave people were openly crying…

“So, as each wave came to an end, we have tried to find ways to help people to decompress. After wave one, the staff at Chris Hani Baragwanath joined together and won the title of best hospital in the Jerusalema challenge. That cemented camaraderie.”

During the second wave they introduced what she calls “Covid confidential”: sessions where doctors and nurses could “vent and share their experiences”. Then, when the Sisonke vaccination roll-out for healthcare workers started, “we were the first team to be vaccinated on day one. That recognition and the vaccine itself lifted morale.”

Now the third wave has subsided – admissions have halved to “only” 250 people (still more than most hospitals in the world) – she wants to organise a friendly soccer match and is hatching plans for how to celebrate the 80th anniversary of the hospital next year.

We finish by talking about “Bara” and why the three doctors, and many others, choose to work in the public health system, despite all its problems and pressures.

“Bara,” Makan says, “may not look like the prettiest hospital, but the medical care here is of a very high quality. Working here is an opportunity to help a lot of people … and that’s why you do medicine.”

Moore puts it another way: “South African clinicians are tough and resilient. What drives us is patient care. If we walk away, what happens? Patients don’t get to walk away.” DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider