OLYMPICS

The silent Games showcase the changing views and demographics of Japan

The 2020 Tokyo Olympics are generating some unexpected human stories, about Japan, and the lives of athletes in the Games.

A personal memory. There I was, perched precariously on my skis, right at the top of the course, poised at the jump-off point for the men’s giant slalom ski course — the actual Winter Olympics course — located in Japan’s Teine Highland ski resort on the island of Hokkaido. From the end of the course, way down at the bottom of the hill (maybe it really was a modest mountain?), it didn’t look so fearsome, I thought. It simply looked like an extended version of the shorter runs where I had been learning the rudiments of some very modest skills at skiing during the past several weekends. But up there where the Olympians had begun those blisteringly fast runs, looking down to the finish line, it now seemed like a nearly vertical, limitless drop into an abyss of white, with the trees flanking the course reduced to tiny models for toy train layouts.

“Okay,” I tell myself, “no more stalling, time to push off.” The honour of the US rested on my suddenly very nervous, less than skilful shoulders, knees, ankles, feet, and legs as I began my descent. “Take it slowly, find your rhythm, keep your balance, keep that centre of gravity low to the ground,” my inner coach kept whispering. “And don’t fall.” Since everyone was now watching my run from the finish line, if I fell I would easily be the most embarrassed person in all of Japan.

Eventually I found my pace going down that hill. I moved slowly, but I kept moving. But “slowly” was the key word here. After some minutes, the ski run managers and my coach were apparently starting to worry about what had happened to me. Where was I? Had I fallen and broken a limb? Worse, had I run into a tree or rock on the margins of the course and was lying unconscious? Or had I lost my nerve entirely and was now frozen in place?

Soon enough, one of the ski-lift workers came whizzing up to me (down to me, actually from the chair lift at the top of the course) to check if I was still alive, especially since they were getting close to the end of their workday and they wanted to inspect the course before dark. In the end, I seem to have set a course record there — and it is probably one that still stands unchallenged, after some 35 years — for the slowest descent on that particular course, ever.

By contrast, my four-year-old daughter, still too young to ski on her own, was taken to the top of that same course by the man who operated this sports park. This was the legendary Yuichiro Miura, the man who had been profiled in the 1975 documentary film The Man Who Skied Down Everest. He brought her down that same course in just a fraction of my time, safely tucked between his legs as he did a speedy run down the hill. He was, of course, someone who had been tackling this and similar hills since he had been just a little older than my daughter, and knew every bit of the run by heart.

By the time they reached the bottom, my daughter had a smile permanently pasted on her face, and a feeling that powered her on into snowboarding more than a decade later. Between us, we had conquered a real-live, genuine, championship Olympic ski run. Check that box!

Sapporo was the site for the 1972 Winter Olympics, in part to take advantage of the island’s natural beauty, but also to give the region’s economy a boost as a tourist and outdoor paradise since its economic life was still largely dependent on declining industries such as timber, pulp and paper, some agriculture, and the exploitation of a few primary minerals. As a result, they created all the stadiums, speed skating rinks, ski jumps and downhill skiing courses needed for an extravaganza of a winter Olympics.

Now Sapporo has more than a dozen ski lifts accessible by public transport and almost everybody, it seems, skis there. Of course, to prepare for the Olympics, it meant the city and the surrounding region had pushed ahead with upgraded transportation networks and facilities, including modern subways, spanking new hotels and parks, underground all-weather shopping arcades and downtown office buildings connected to those subways through weather-controlled tunnels, and the kinds of new roads that now, inevitably, all go hand-in-hand with a winning Olympics bid (or a World Cup rugby bid, for that matter, lest we forget).

Sapporo’s 1972 Winter Olympics had been staged just eight years after the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics. That particular Olympics extravaganza had been deliberately positioned as a kind of “coming out party” for Japan’s resurgence as a major manufacturing and financial power after the near-total devastation that had been visited upon the country as a result of its defeat in World War 2, less than two decades earlier.

A Shinkansen bullet train travels along an elevated railway track near Yurakucho station in Tokyo. (Photo: Supplied)

Modernist stadiums and all the other Olympic facilities were constructed bang on schedule, just like the Japanese do so many things. Acres of the near-shack settlements that still remained from the immediate post-war period were removed to make way for the new. And then there was the pride and joy of the new Japan, the “Shinkansen” — those now-famous bullet trains — brought into operation to coincide with this Olympics. The Shinkansen became both a symbol for the Olympics and a legacy for the country’s future. Eventually, this rail network reached much of the nation, complete with vast tunnels through the country’s mountain spine and to connect the islands of Kyushu and Honshu.

The Olympic movement, as used by host cities (and regional and national governments) that win the bids, has become a way of bulling through new construction such as those bullet trains. And they usually end up costing a fortune and registering major overruns and real deficits versus expected revenue. The 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles stands out as the only one of these in the modern era to show an actual profit. This was primarily because organisers undertook the unusual decision to minimise new construction and concentrate on renovating the city’s already plentiful existing stock of sports facilities. Given the city’s plethora of professional and university sports teams with high-quality facilities, that choice turned out to be a good business decision.

From where we sit now, the currently ongoing Tokyo Olympics almost seems to have come from a different era — and now seems increasingly cursed by circumstances. Pushed hard by then-prime minister Shinzo Abe, along with other powerful politicians, this second Tokyo Olympics was supposed to demonstrate in a visceral, concrete way that Japan was now back in business: bigger, shinier, newer, better than ever.

It was true that long gone were the feelings of the 1980s when Japan was the implacable economic competitor sweeping all before it, back at a time when it was estimated that the value of the real estate the Imperial Palace in central Tokyo stood on had a value higher than all the real estate in the entire state of California. But, fortunately, gone, too, would be the depressing feelings about all those lost years of economic doldrums or malaise when so many of the nation’s economic and manufacturing powerhouses were stuck in pause mode, or worse.

A passerby walks past an Olympic Rings display near the National Stadium, the main venue of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Franck Robichon)

As with their earlier Games, the country’s best architectural talent was put to work, the facilities were built on schedule; but then, just as the 2020 Olympics were right on the horizon, BOOM, Covid struck and the lockdowns began. Eventually, the Japanese and the International Olympic Committee reached the inevitable conclusion that the 2020 event would be required to suffer a postponement for a full year.

But by the time the organisers were ready to launch the now-delayed event a year later, the stubborn Covid pandemic had still refused to fade away (and now, a year later, still with so few Japanese fully vaccinated against it). To salvage what they could, the organisers took the unprecedented (and increasingly unpopular with Japanese citizens) decision to go ahead with the Games, but without attendance by fans.

Thus there is now the Olympics, but one with virtually empty stadiums, save for the competitors, officials and media. The opening ceremonies ultimately had fewer than a thousand people watching live in the stands — a smaller number than the athletes gathered together on the field. The athletes’ village had all manner of lockdown rules in place that have almost made it impossible for the kind of fraternising that is a hallmark of the Games.

The whole thing has been taking place without the kinds of cheering and emotional outpouring that encourages athletes to run, jump, throw, swim, dive, ride, and hit various kinds of balls and projectiles higher, harder, and faster. Watching the Games on television gives home audiences a chance to see it all, close up, but for the athletes, these Games must be deeply unnerving as they attempt to achieve their collective bests inside large, empty venues meant to hold tens of thousands of fans.

And, of course, the ticket revenue is now lost, and even some global sponsors such as Toyota have forgone the chances to advertise their participation in their home nation — although not internationally. For the organisers, by the end of things, the Games will lose billions of dollars, a cost that will eventually be absorbed by the Japanese taxpayers.

Paradoxically, so far at least, despite not appearing before the home crowd, the Games have been very successful for Japanese athletes. As things stood at the time of this writing, halfway through the Games, Japan was in a surprising third place in gold medals (behind the US and China) and with a considerable haul of silver and bronze medals in a wide range of sporting codes as well.

There is one other noteworthy feature of Japan’s presence in the Games. This is how much the home team is reflecting the (slowly) changing nature of Japan’s view of itself as an absolutely homogenous nation and population. In fact, a number of its best athletes have come either from what the Japanese call the hafu (or half Japanese) population or from among ethnic Japanese who have grown up abroad or now live outside Japan.

Kanoa Igarashi in action at the Oi Rio Pro surfing event in Rio de Janeiro. Igarashi has become the visible star of the Olympics souvenir and marketing effort, with his image appearing on everything from tote bags to banners and posters all around Tokyo. (Photo: World Surf League)

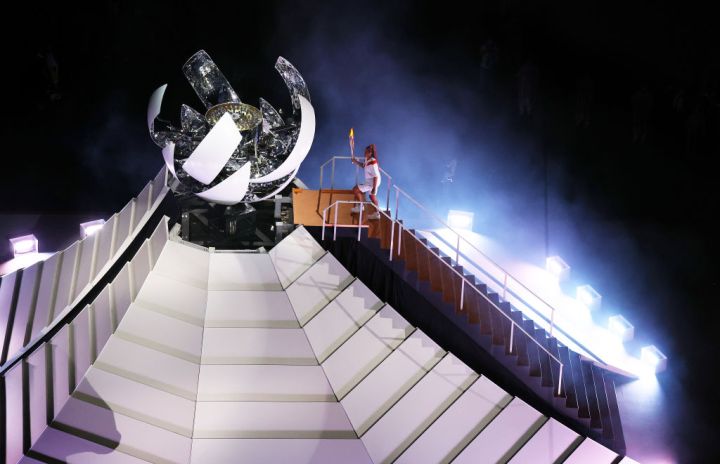

By now, Olympic Games fans surely know that Japanese-Haitian-American tennis great Naomi Osaka lit the torch to launch the Games officially on a billion global television screens (even if she has now been eliminated in the women’s tennis competition), while Rui Hachimura, a global basketball star with a Japanese mother and a Beninois father carried Japan’s flag into the arena during the Games’ opening ceremony. But there are also the Ghanaian-Japanese sprinter Abdul Hakim Sani Brown and the Iranian-Japanese baseball star Yu Darvish on the team. And Japanese-American surfer dude Kanoa Igarashi has become the visible star of the Olympics souvenir and marketing effort, with his image appearing on everything from tote bags to banners and posters all around Tokyo.

Despite the obvious examples of abuse and hate speech that even such stars as these must endure too often, change does seem to be in the air, from demographic trends, if not from obvious changes of heart on the part of millions of Japanese.

As The Economist noted, “There are also more foreigners in Japan than at any time in its post-war history. A stealth immigration campaign to make up for Japan’s shrinking population has seen the numbers of foreigners living there grow from some 2m a decade ago to nearly 3m today. That amounts to just 2% of the overall population, but the share is much higher among city-dwellers and the young: at least 10% of 20-somethings in Tokyo are foreign-born. (Japan does not collect statistics on the ethnic background of its citizens, only their nationality.)

“The stigma around marrying foreigners is fading: in 1993, 30% of Japanese approved of international marriages, while 34% disapproved; by 2013, the last year for which data are available, 56% approved and 20% did not. One in every 50 babies is now born to a mixed couple, up from one in every 135 in the late 1980s. As Mr Hachimura and his peers show, their potential is enormous.”

Simone Biles of the US competes on the vault during the women’s qualification of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games Artistic Gymnastics events at the Ariake Gymnastics Centre in Tokyo, Japan, 25 July 2021. (Photo: EPA-EFE / HOW HWEE YOUNG)

These Games have, of course, also highlighted the all-too-human frailties of those competing athletes. Gymnastics superstar Simone Biles has withdrawn herself from the competition over a psychological crisis (the “twisties” as she called it, of having lost that all-important muscle memory that brings together speed, movement, constantly changing orientation, and balance) that in another time might have been quietly swept under the rug.

Instead, this time around, Biles’ announcement is generating a groundswell of understanding and sympathy for her — and, by extension, for all other athletes who confront similar challenges and circumstances specific to their sports. Despite the absence of spectators in the stands, Biles’ honesty has touched millions, and it may, in fact, herald a better understanding by fans of the psychological stresses athletes at the apex heights of their respective skills often endure in order to respond to their inner competitiveness — and for the entertainment of fans and spectators.

In the end, the ultimate paradox of this year’s Olympics is that these Games may have come to focus on the more human stories rather than just who won what medal, even as so few people actually get to see those competitions first-hand. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.