LOVE, UNSTOPPABLE

On love across time and the Irish Sea

As with many journeys in life, the story of an unwed mother in 1970s Ireland took many surprising turns until, many years later, life came full circle in an ultimate tribute to lost love, sorrow, regrets… and more love.

In January 2021, Irish Prime Minister Micheál Martin formally apologised for the state’s “profound failure” in its treatment of unmarried mothers and their babies from the 1920s to the 1990s.

During this period, thousands of children died in Ireland’s Mother and Baby Homes, and “around 56,000 unmarried mothers, some as young as 12, passed through, and 57,000 children were born”, a report by Ireland’s Commission of Investigation found.

Ireland is estimated to have had the highest proportion of unwed mothers admitted to such homes in the 20th century, with many pregnant single women feeling they had nowhere else to go.

This is the story of one of those mothers, who walked away from her family, from her village, and left everything behind, carrying within her a baby she wanted to be born.

***

In 1967, Marion was studying to be a nurse. She was about to write her nursing finals, and had tagged along with her brother Tom, her cousin Liam and their friend Jim as they went partying in Belfast.

A few months later, Marion was pregnant with Jim’s baby. The pregnancy was unexpected; she wasn’t a married woman and having a baby as a single mother was not something that was tolerated – she knew being an unwed mother would bring shame on her family, affecting marriage possibilities for her extended family, too.

Raised by staunch Catholics in Belcoo, a rural village in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, she realised that her only solution was to leave for London to have her baby and put the child up for adoption there.

Before Marion left, Jim, knowing she was pregnant, had told her that he would “do the right thing” should she keep the baby. But for Marion “standing by her side” wasn’t enough – it wasn’t love, and certainly not the love she carried for him. She was young and hoped for more and so, one morning, she packed her suitcase and left.

On the outside, her plan was “simple”: she was leaving Ireland telling people she was going for nursing; once the pregnancy was over, she would come back and nobody would have known. Except that, while in London, Marion changed her mind – she wanted to keep the baby. And that meant that going back to her home in Ireland, unmarried and a single mother, was no longer an option; she would not return home until 30 years later.

She arrived at the Catholic Mother and Baby Home in Lambeth, London, where the sisters were firm but fair – she was fortunate, the home was very different to many mother and baby homes in Ireland. Marion was allowed to stay 12 weeks, six weeks before and six weeks after the baby was born; for the girls who decided their babies were going to get put up for adoption, the nuns were strict about not letting them see the infants.

There, all the women but Marion and an American girl gave their children up for adoption. It is impossible to express the pain they might have endured, the guilt they must have carried, the emptiness that must have filled their beings having to make such a decision.

Even though she could not return to Ireland, nobody really cared in London; it was a fresh start, she wanted to be judged on how good she was at her job, not the “mistakes” that she’d made having a baby.

On 9 March 1968, Marion gave birth.

That baby was me, christened Josephine Terese Parker.

***

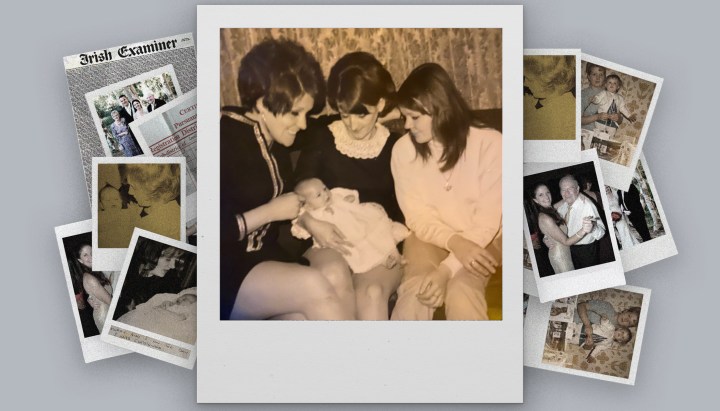

I was named after Marion’s best friend, Josephine, who reckoned she knew even before Marion did that she would keep the baby.

The decision my mother made to keep me still threatened to derail her plans of studying to be a nurse, until Josephine and two other nursing friends rallied, offering to stand by her and help. Jo, Hazel and Irene followed Marion to London and rented a flat together, telling the landlord that the baby was someone else’s and that they were just babysitting for some extra money. The four of them devised a shift system, making sure one of them was always home to look after the baby.

Needing the extra money to support herself and her baby, Marion then qualified to be a hairdresser on top of her nursing qualifications. One of her hairdressing clients, a larger-than-life Irish landlady named Rita, offered a room above the bar for the two of us rent-free, in exchange for Marion helping tend the bar. This gave my mother her first independence, a place of her own and a steady, growing income to save for her and her baby’s future.

Once she was fully qualified as a nurse, she was able to leave the bar work and continue nursing full time, leaving London for Cheshire with me as a toddler; I was now two years old. For the next two years, with the emotional support of a few family members in England who hadn’t shunned her, we shared some idyllic days in the countryside.

Then she met my stepdad – a part of the story we rarely discuss.

As I see it, she was grateful that a man would take on and marry a single mother in the early 70s. She felt a stepdad was better than no dad, and in fairness, she did love him. Sadly, I did not. He was an impatient, bad-tempered and unkind man whom I rebelled against.

***

At the age of 20, I decided to leave for a year and travelled to South Africa. I fell in love with the place, determined to build a life of my own here. It might have been the move, a new world opening in front of my eyes, but it was then, far from my country of birth that I felt the urge to know more about my biological father, and to reach out to him.

Marion had expected that I would, one day, be curious and ask to know more about my father; she asked my godfather Liam, who had remained friends with his varsity friend, to send me Jim’s address. Back then, in the 90s, the quickest way to get in touch was by telegram. My message was short: I told him that I now lived in South Africa and was emigrating to build my life here, but that I would be in the UK and Ireland in December. “I would like to meet you and perhaps get to know you,” I said – signing off, “From your daughter, Josephine.”

As an afterthought, I added my phone number, as I couldn’t bear the wait of not knowing if he would agree to or want to meet me.

Within 48 hours, Jim phoned back. I cannot recall much of that call, save that he said he would be delighted to meet me. Jim, who was in the throes of divorce, and losing custody of his three children at the time, was overjoyed to get to know his true first born.

When making the final arrangements for him to meet me off the bus from the ferry to Belfast, he told me he would be wearing a navy blue raincoat; I told him I would be wearing brown ski pants and an Aran jersey. But then, my mother insisted that to cross the Irish sea on a ferry in the dead of winter, I should put on jeans, a leather jacket and a scarf, which I did.

How would Jim recognise me then?

There were three men standing on the platform in navy blue raincoats, so I decided to wait and be the last off the bus so I wouldn’t approach the wrong man. Jim said the minute he saw me anxiously looking out from the bus window, he knew it was me as I looked just like my mother.

I was only 22, awkward and very nervous. When we arrived at a lovely semi-detached home in west Belfast, my half siblings were there to greet me. I tried to feel at home, but these were strangers, and it was all very surreal and strange.

We had a meal together and I was suddenly overwhelmed. I asked if I could call my mum to let her know I’d arrived safely. To my dismay, as I sat at the bottom of the stairs by the front door and dialed, Marion burst into tears upon hearing my voice.

Why? I asked, for she had been nothing but supportive of me making this journey. Because, she said, despite her always expecting it and genuinely supporting it, she thought perhaps with my father I would find love that I hadn’t with my stepdad, and was uncertain how that might affect our own close relationship.

I thought I’d made a huge mistake. When I returned, I asked if they would mind me turning in, claiming to be tired from the journey, but truly because I was heartbroken at mum’s tears and wondered if it had been worth my curiosity, sitting here with these relative strangers and hurting my mum as I felt I had.

Jim kindly showed me to my sister’s room with its pretty flowered wallpaper. I unpacked and went to brush my teeth. On my way back across the landing, I heard giggles behind the closed door of another bedroom, I knocked quietly and looked in. There were my late-teen siblings and a friend all in a circle on the floor. I saw my brother hide something. I asked if that was wine? He blushed and said “erm… yeah?”

To their delight, I told them I’d brought some South African wine, how about we open that up? I went in and got down on the floor with them, and we never really looked back.

I don’t know what time we got to bed that night, I do remember we heard a creaking on the landing and we all shushed in stage whispers, realising our father must be outside the door, but we couldn’t suppress our giggles. Later on, he told me he couldn’t care less what we were up to, it just made his heart happy to hear all of his children, finally under the same roof, laughing and happy, together.

My dad was a very kind soul. And my siblings were all very excited and fascinated by me. We found our way, and we became very close during that first visit. Over the years, and across the miles, my biological father, and my half siblings and I developed a loving and cherished relationship.

***

In 2007, on our first trip to Ireland together to introduce my then boyfriend Pierre, Jim and Marion both decided to welcome us at the airport. As we all went to my godmother Josephine’s home for a kitchen supper before Jim’s return to Belfast, I couldn’t help thinking: could there be a romantic spark? In fact, it simply was a truce among old friends that had allowed us all to eat together at one table. What a gift. It was enough.

Six months later, I got married in Cape Town, and once again, Marion and Jim met. At the time, Marion had separated, and Jim was still single. He walked me down the aisle and I remember that at some point during the evening reception my mother and my father danced together, eyes shining with joy.

But it was only some days later, when we said our final goodbyes to my father, as he was to leave for the airport early the next day, that I realised something had changed. As he disappeared, my mother’s face changed, tears rolling down her cheeks. She didn’t say much but the words she murmured spoke of lost love, sorrow, regrets and more love…

Life always takes us on surprising journeys and years later, here they were, at the marriage of their daughter, a life almost coming full circle – at least in her heart. And full circle it would come.

Eight weeks later, my mother called. The tears from only a few months ago had disappeared, replaced by sheer youthful excitement: she was going on a date and her date was Jim.

In fact, they rekindled their romance, a courtship that seemed to fill all that they had missed the first time. Jim was the opposite of my stepfather: he was kind, considerate, gentle and generous. Not perfect, but as near as, dammit!

***

In 2000, Marion had finally moved back to Fermanagh. In the village she wouldn’t have dared to go back to being a single mother with a child, now, nobody seemed to mind. The family elders were less inclined to judge her all these years later, and perhaps in secret, were proud that she had made a success of her life despite the “setback”.

Jim began spending the weekends with her in Belcoo, and would make the two-hour drive to Belfast on Sundays to help take care of his grandchildren during the week.

They were a good fit, and Jim had completely fallen in love with Marion, just as during all the years later, she had never stopped loving him. And thus followed several years of bliss, a lightness of being made of cherished moments.

Jim turned 70 on 31 January 2013. Later that year, we planned to visit our mutual American family with Jim and Marion, so Pierre and I decided against flying to join my siblings and the grandchildren for a surprise weekend at a lake house in Fermanagh. But behind the scenes we all planned, prepared and organised the celebrations together: we joined for a virtual sláinte across the miles, watching my parents beaming in their revived love. That year, he had decided to propose; he would finally marry the mother of his first child.

He had spoken to his children, he had spoken to their mother, so everybody knew that was the next step, they were looking forward to their winter years together.

On a cloudy Monday morning on 12 February 2013, as Jim got into his car to drive back to Belfast, he put his sunglasses in his breast pocket, despite the typical low Fermanagh skies, turned to Marion and said: “Our daughter always says, you never know when the sun might shine.” And with that, they waved a fond farewell as Jim drove back to Belfast, with plans to return to celebrate Valentine’s weekend together.

The following evening, while having a pint with his best friend, Jim had a heart attack. He was minutes away from the Royal Victoria in Belfast and the medical team did all that they possibly could to keep him alive.

A few hours later, he passed.

He never married my mother. But he was going to – and sometimes, knowing the intention is enough to fill the void he left when he died. As a reminder, my mother wears the Claddagh ring he never had the chance to give her. The heart is closed, as is the tradition for one whose heart is taken. Her heart remains yours, Jim. Forever. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

If this had been written on paper …the paper would be wet

With tears

What a beautiful, moving story. It reminds me of this lovely line in Max Ehrmann’s Desiderata

“Neither be critical about love; for in the face of all aridity and disenchantment it is as perennial as the grass.”

… a sentiment echoed in Corinthians 13:4-8

Tears in my eyes when I finished reading. Thank for sharing this heartbreaking yet heartwarming tale.

In this time of hate and such unkindness the reminder that love conquers as it endures is so uplifting and encouraging. Thank you for sharing. Marion, a true heart, a strong and loving mother.

Such a beautiful story Jo. Your Mum sounds warm and courageous and strong. Thank you for sharing it with us.