PODCAST REVIEW

This week we’re listening: On the real meaning of The Great Gatsby and clichéd sunsets

Alongside his new book of the same name, author John Green’s podcast, ‘The Anthropocene Reviewed’, is a testament to the splendour of ordinary life. In the episodes, Green reviews aspects of our world, giving them a rating out of five and leaving the listener with both sparks of joy and a little more literary knowledge to impress the local bibliophile.

Capacity for Wonder and Sunsets – The Anthropocene Reviewed

- Format: Single episode

- Year: 2019

- Listen on: Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you find your podcasts.

John Green’s narration is effortlessly soothing and ever enticing. His words carry the mark of a true storyteller, so that even when you are not entirely sure what point he is weaving, you are more than happy to sit and listen anyway. He does get there in the end, though in an entirely different way than expected.

Although, with a podcast series that “reviews different facets of the human-centered planet on a five-star scale”, I’m not quite sure what one does expect – when the objects of scrutiny are sunsets and humanity’s capacity for wonder.

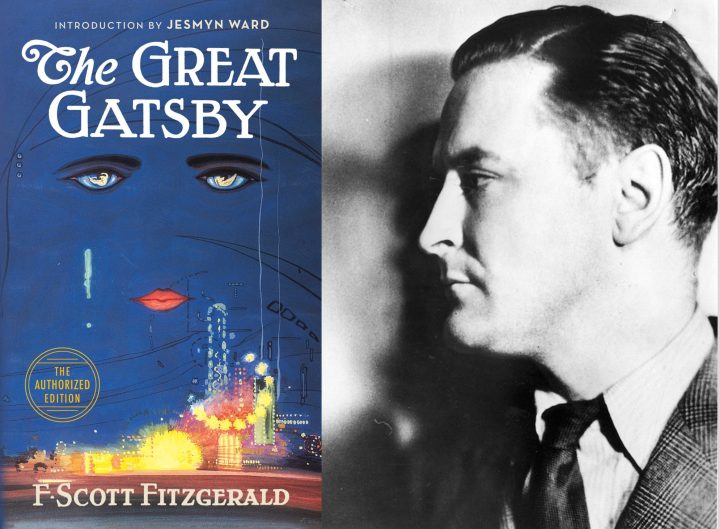

In the first part of the episode, Green comments on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in a literary analysis of the understanding of beauty and awe:

“For a transitory enchanted moment, man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

Green posits that the novel, almost one hundred years from when it was published, is still misunderstood – in fact, Fitzgerald once told a friend, “Of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about.”

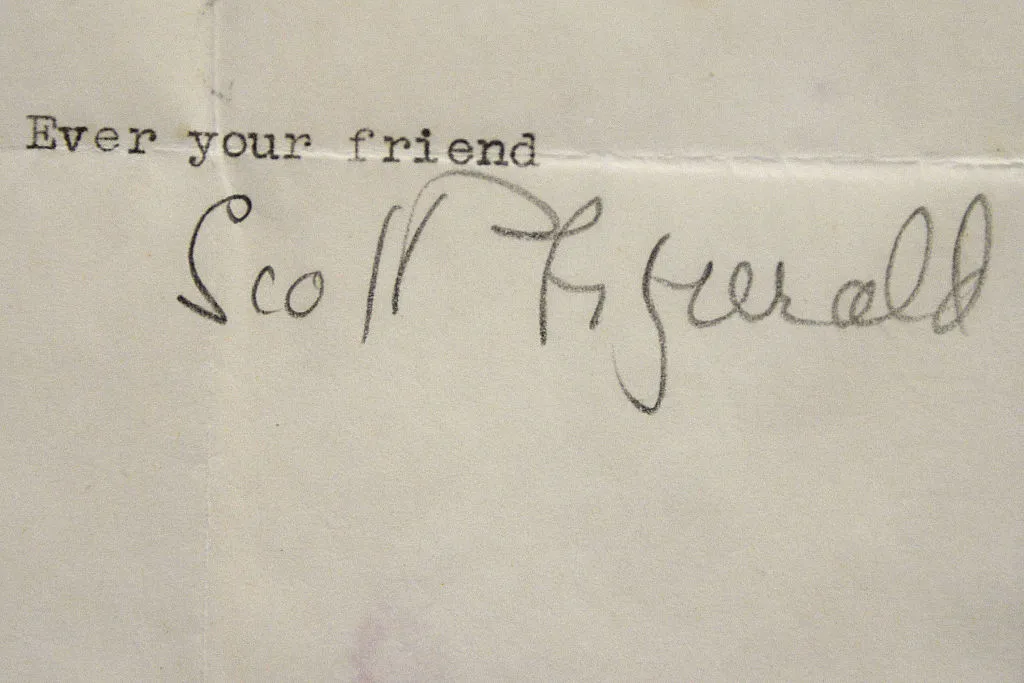

Typed letter signed by F. Scott Fitzgerald, one month before his death at the Rare Titanic Artifacts from Lifeboat No. 1 & Other Historic Autographs – Auction Sneak Peak at Lion Heart Autographs on September 28, 2015 in New York City. (Photo by Ben Gabbe/Getty Images)

Rather, the novel is a “critique of the American Dream” that “lays bare the carelessness of the entitled rich”, Green says.

But it is instead remembered for excess, the glitz and the glamour, a “celebration of the horrifying debauchery of the Anthropocene’s richer realms,” Green believes.

Consider the ending of the novel, where (spoiler alert) Gatsby is dead, all is silent, the lights are out and the party’s over.

“Here we are at the end of a novel in which everyone is trying to return to a past that never really existed, and our narrator is suddenly trying to return to a past that never really existed,” Green reflects.

“Maybe the novel knows that any attempt to hearken back to a Golden Age is doomed, and yet we go on hearkening anyway.”

The work is often used as a glimpse into Prohibition-era America and the “Roaring Twenties”, but almost a century later, reading Gatsby in that vacuum is an oversight. Because in 2021, not much has changed, really. We are still enchanted by the romances of Gatsbys and Daisys, and eyes are caught by things that sparkle even when, as the Shakespearean adage goes, all that glisters is not gold.

So what does this have to do with wonder?

Green recalls a moment with his son, as they walked through the woods.

“We were along a ridge, looking down at a forest in the valley below, where a cold haze seemed to hug the forest floor. And I kept trying to get my oblivious two-year-old to appreciate this extraordinary landscape. At one point I picked him up and pointed out toward the horizon and said ‘Look at that, Henry, just look at it!’ And he said, ‘Leaf!’ I said, ‘What?’ And again he said, ‘Leaf’, and then reached out and grabbed a single brown oak leaf from the little tree next to us,” Green relates.

What is so special about a leaf? To a toddler, everything, and as they looked, Green began to see what his son saw.

“Its veins spidered out red and orange and yellow in a pattern too complex for my brain to synthesize, and the more I looked at the leaf with Henry, the more I knew I was face-to-face with something commensurate to my capacity for wonder.

“The magnificence of that leaf astonished me, and I was reminded that aesthetic beauty is as much about how and whether you look, as what you see.”

Perhaps then we are too caught up in what we think we ought to be awed by. Suddenly, Green’s analysis of The Great Gatsby makes sense.

Was that not Gatsby’s whole mission, to capture the attention of his Daisy? And we look on, eyes wide at man-made splendour, when the real magic is in the beauty of an oak tree leaf, waiting for us to notice.

“How we pay attention and what we pay attention to ends up shaping the world we share in ways we often don’t pay attention to,” Green says, about his book, The Anthropocene Reviewed.

“From the quark to the supernova, the wonders do not cease. It is our attentiveness that is in short supply, our ability and willingness to do the work that awe requires,” Green says.

“Really, we are never far from wonders.”

Pay attention.

***

In the second part of the episode, Green ponders: “What are we to do about the cliched beauty of a really phenomenal sunset?”

Cliched beauty? He explains: “Whenever I see the sun sink below a distant horizon as the yellows and oranges and pinks flood the sky, I inevitably think, ‘This looks like a picture that has been extensively photoshopped’. When I see the natural world at its most spectacular, my general impression is that more than anything, it looks fake.

“The thing about the sun, of course, is that you can’t look directly at it – not when you’re outside and not when you’re trying to describe its beauty,” he says, before quoting author Annie Dillard:

“We have really only that one light, one source for all power, and yet we must turn away from it by universal decree. Nobody here on the planet seems aware of this strange, powerful taboo, that we all walk around carefully averting our faces this way and that, lest our eyes be blasted forever.”

Perhaps that is why we are drawn to sunsets, as the only time we can (almost) look right at it is just before it slips below the horizon, holding onto its mystery.

Moon rise in the Karoo Image: Emilie Gambade

“In all those senses, the sun is kind of like a god – as T.S. Eliot put it, light is the visible reminder of the Invisible Light. Like a god, the sun has fearsome and wondrous power. And like a god, the sun is difficult or even dangerous to look at,” Green poses, describing how throughout the millennia, humans have been so enthralled by the sun that it can be found immortalised in religion.

“No wonder that Christian writers have for centuries been punning on Jesus as being both kinds of Son. The Gospel according to John refers to Jesus as “the Light” so many times that it starts to get annoying.

“And there are gods of sunlight wherever there are gods, from the Egyptian Ra to the Greek Helios to the Aztec Nanahuatzin, who sacrificed himself by leaping into a bonfire so that he could become the shining sun,” he explains.

“But now we’re already swimming in sentimental waters; I’ve metaphorised the sunset. First, it seemed photoshopped. Now, it seems godly. And neither of these ways of looking at a sunset will suffice.”

Metaphors and musings aside, Green is unpacking the fleeting moments of a simple sunset and revealing the complexities that make them not so simple at all.

The next addition to the story of sunsets lies in science.

“Here’s what happens: Before a beam of sunlight gets to your eyes, it has many, many interactions with molecules that cause the so-called scattering of light. Different wavelengths are sent off in different directions when interacting with, say, oxygen or nitrogen in the atmosphere.

“But at sunset, the light travels through the atmosphere longer before it reaches our eyes, so that much of the blue and purple has been scattered away before it reaches us, leaving the sky to our eyes rich in reds and pinks and oranges.”

Sunset in the Karoo; Image: Emilie Gambade

Does this take away from the mystery and wonder? Green argues it doesn’t. Rather, it makes it all the more beautiful – in all its extravagant poetry.

“All I can say is that sometimes when the world is between day and night, I’m stopped cold by its splendour, and I feel my absurd smallness, and you’d think that would be sad, but it isn’t. It only makes me grateful.”

What is captivating about Green’s storytelling is his dedication to his subject and his passion in peeling back the layers of a daily natural phenomenon.

“We want to distill life down into single data points or elevator pitches but the reality of human experience is so nuanced and multitudinous,” Green says.

Toni Morrison wrote:

“At some point in life, the world’s beauty becomes enough. You don’t need to photograph, paint, or even remember it. It is enough.”

“So what can we say about the clichéd beauty of sunsets? Perhaps only that they are enough,” Green says.

“So I try to turn toward that scattered light… and I tell myself: This doesn’t look like a picture. And it doesn’t look like a god. It is a sunset, and it is wildly beautiful, and this whole thing you’ve been doing where almost nothing gets five stars because almost nothing is perfect? That’s b.s. So much is perfect. Starting with this.”

“I give sunsets five stars.” DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.