OUR BURNING PLANET

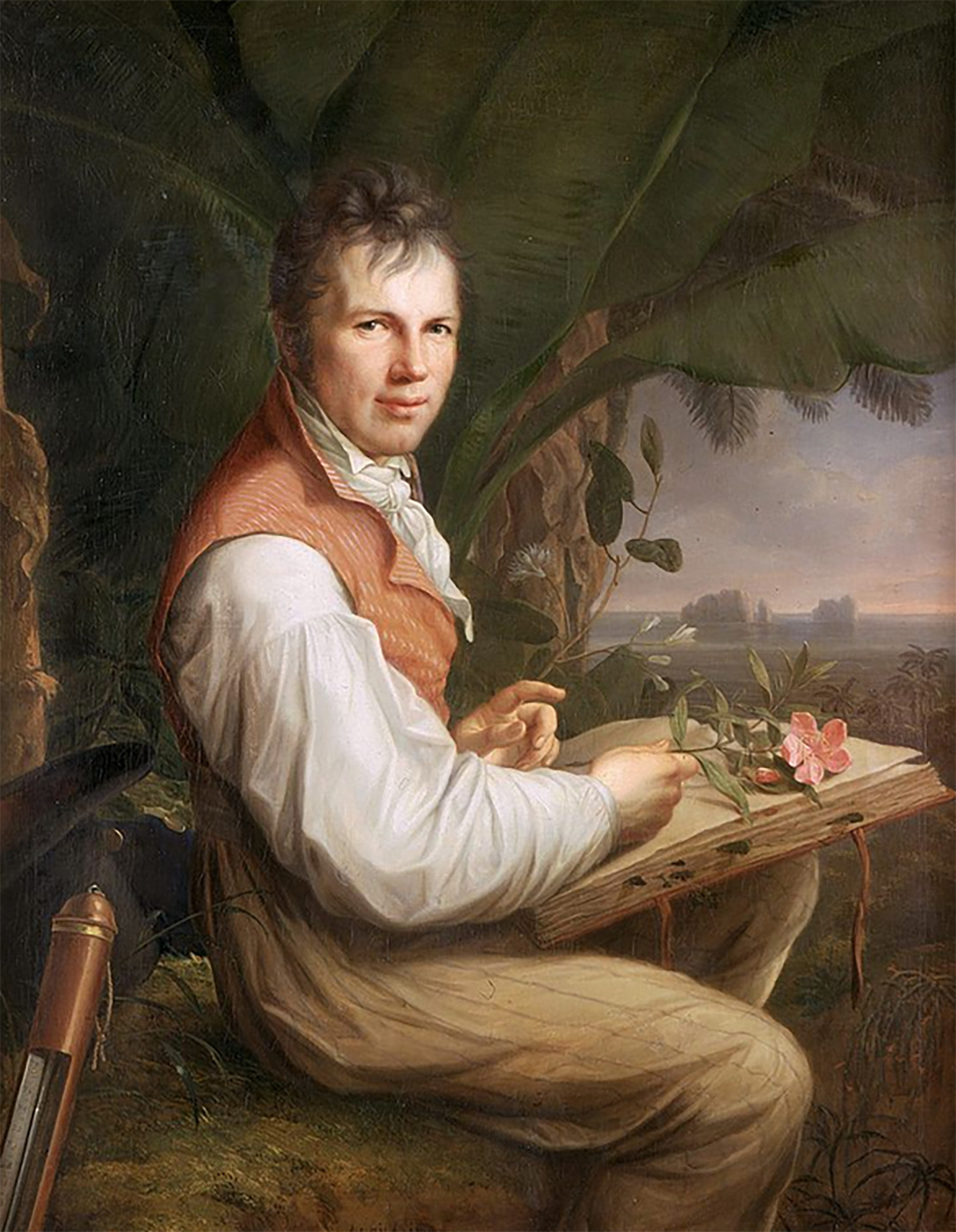

Nature’s Defenders: Alexander von Humboldt – the most important forgotten man of science

He was once the most famous scientist in the world. Now almost nobody remembers him, but his ideas are vital for our time.

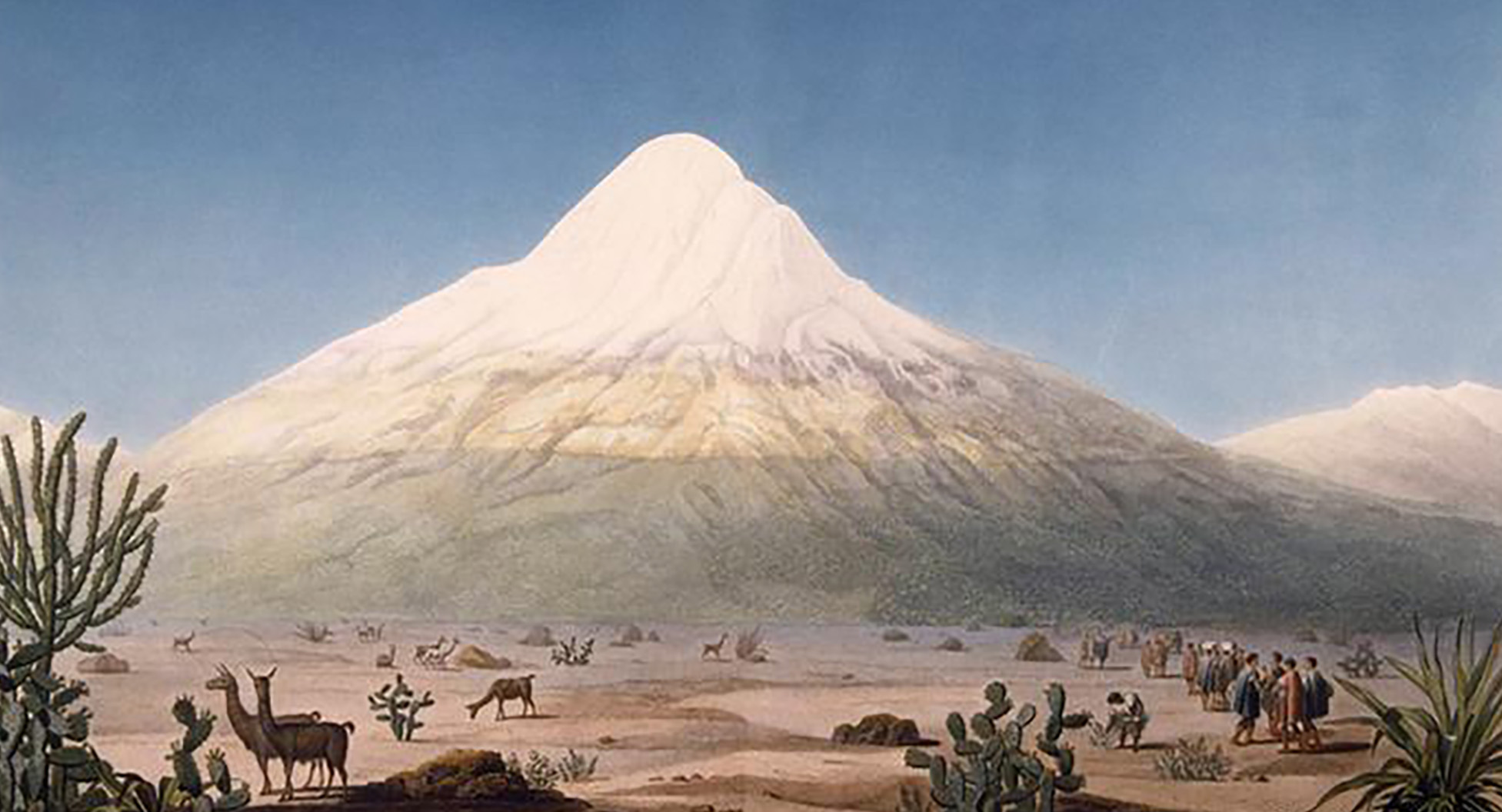

Driven by an insatiable desire to understand the world, Alexander von Humboldt and his friend, French botanist Aimé Bonpland, were dragging their oxygen-starved bodies along ever-narrowing paths up the Andean peak Chimbrazo, then considered the highest mountain in the world. It had never been climbed.

Their inadequate shoes were sodden with melted snow and ice crystals hung from their beards. They inched forward, sometimes crawling in a fog driven by icy wind from which their clothes gave little protection.

On their backs they carried a barometer, thermometer, a sextant, an artificial horizon, a cyanometer to measure the blueness of the sky, a notebook and a pencil. Pausing on precarious ledges, Humboldt set up his instruments with frozen fingers, took measurements and made notes on gravity, altitude and humidity and listed every living thing he saw.

At their highest point, 300m below the peak (an altitude record at the time), the fog lifted. It was 23 June 1802. Humboldt gazed down at mountain peaks and valleys below him and suddenly saw the world differently: life was a fragile, interconnected web, a living whole. This was its resilience and its vulnerability.

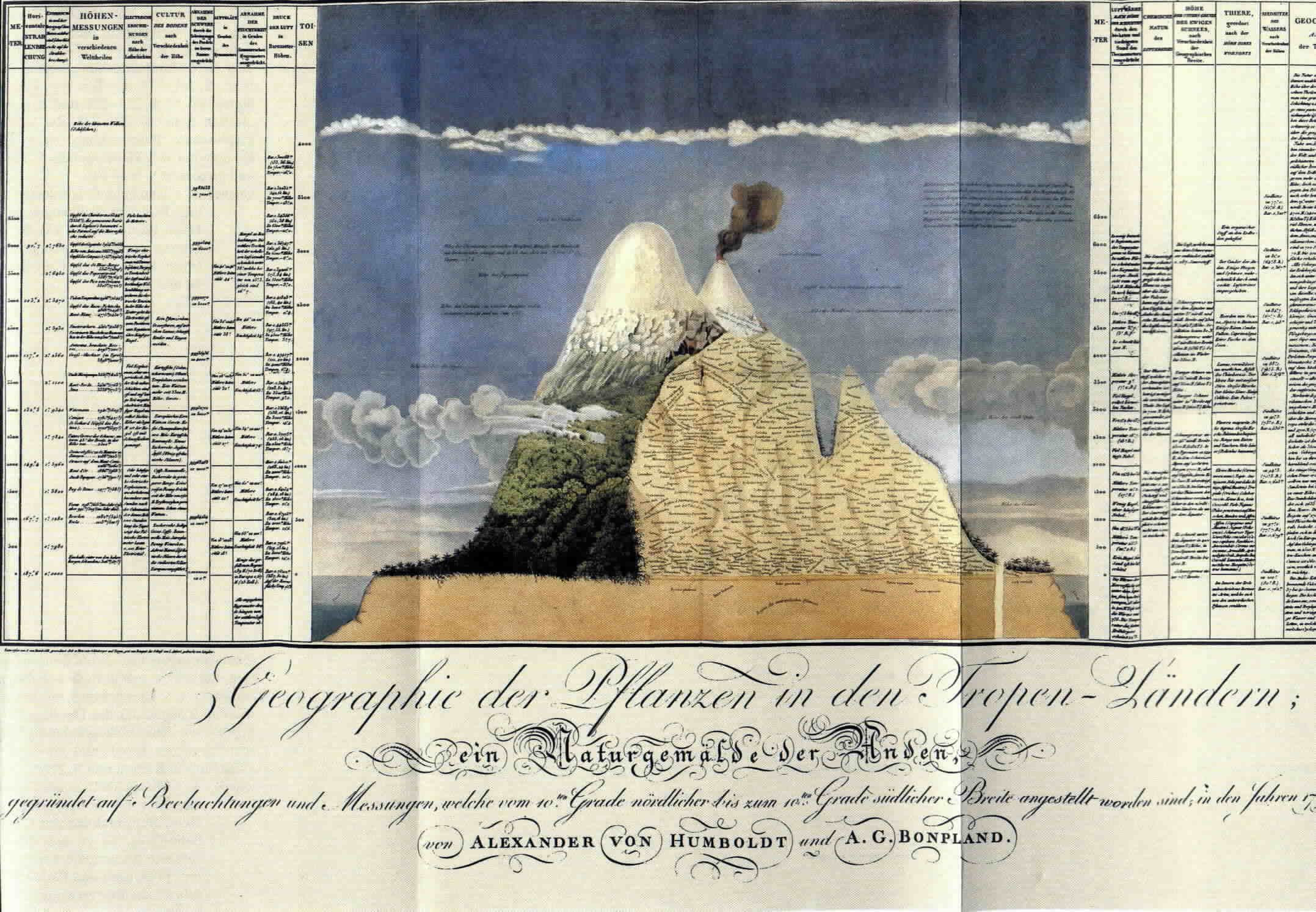

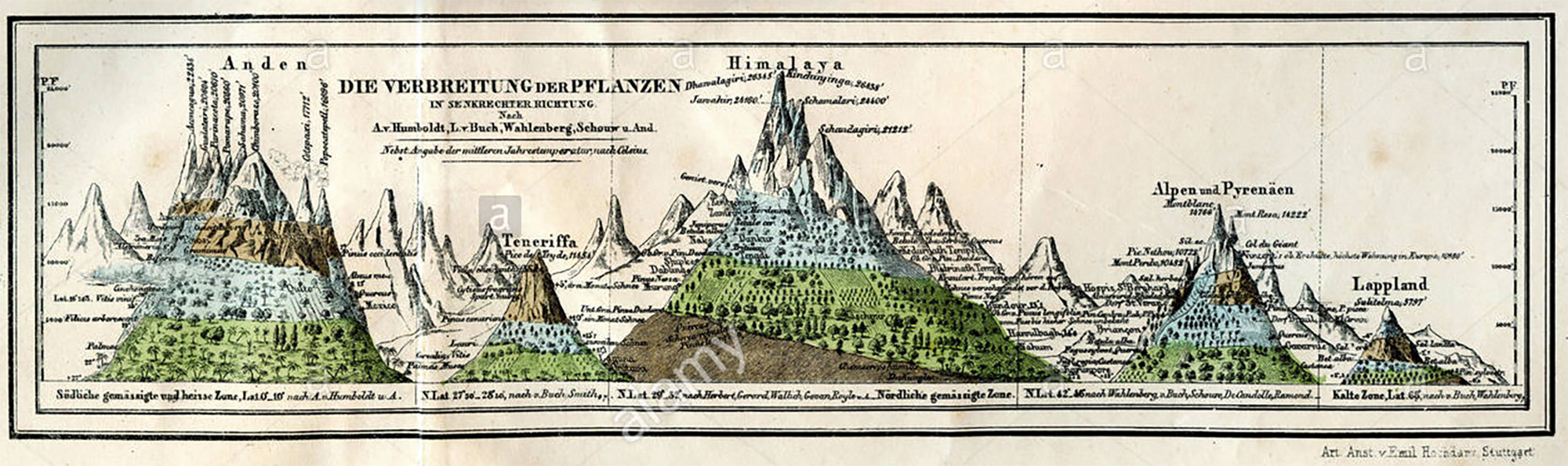

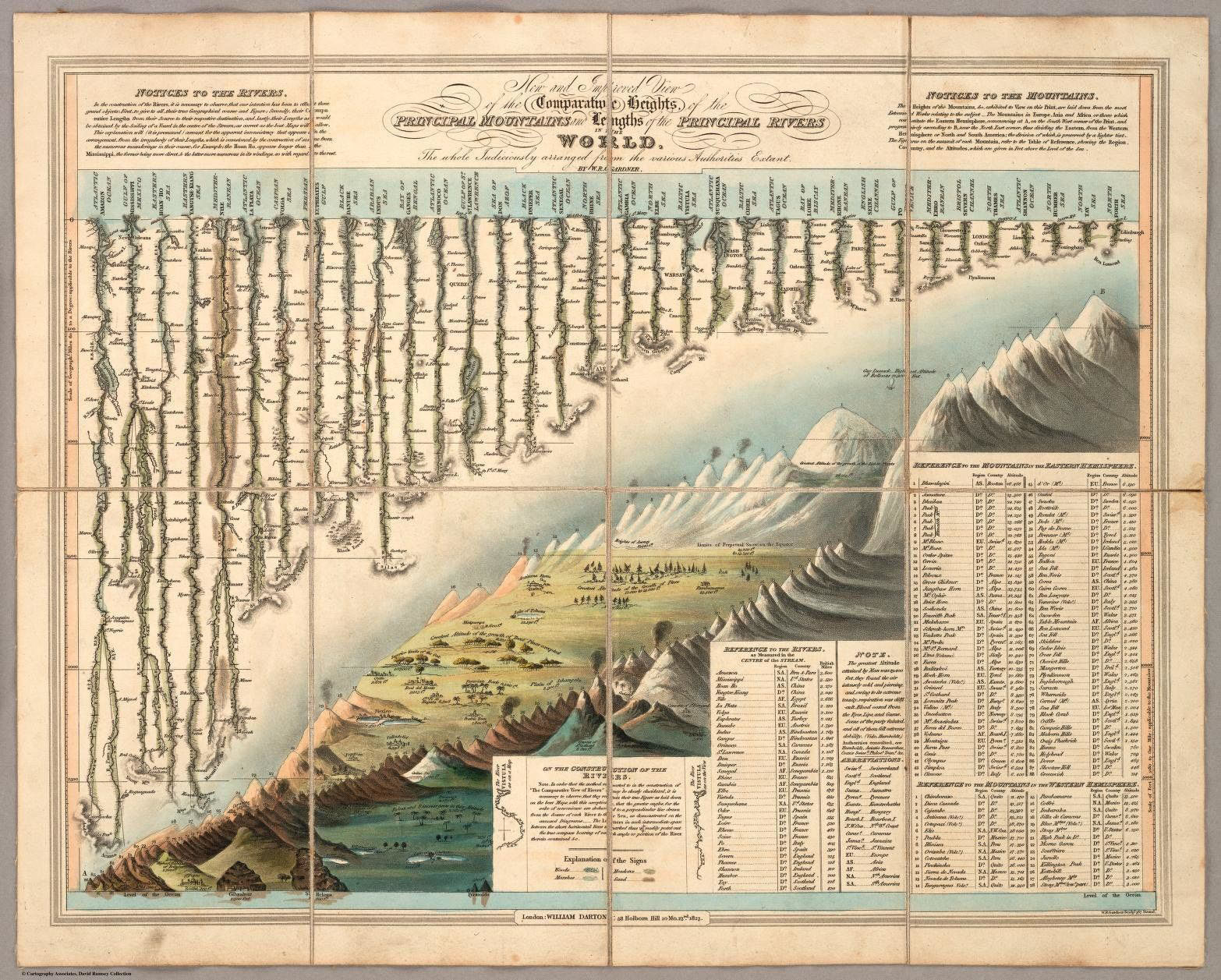

That flash of intuition was to become the anchor of his adventurous explorations across the globe and his prodigious writing. It predated James Lovelock’s Gaia theory by 172 years and an awareness of our precipitation of climate change by 200. It’s an idea at the core of modern ecology. Humboldt encapsulated the future notion of Gaia in a single sentence: “Every one thing exists for the sake of all things and all for the sake of one.”His depictions of that insight, called Naturgemalde, would also be the world’s first infographics. They were able to turn complex scientific data into clear, precise info-maps. To understand, Humboldt insisted, you had to see. The new maps shocked and enthralled the scientific world, which had never seen anything like them before.

Humboldt was born in 1769 into a wealthy, aristocratic Prussian family who owned an estate and castle near Berlin. He and his brother Wilhelm were educated by a string of Enlightenment tutors. Their father died when Alexander was seven and their mother provided all the boys needed apart from her love. Her only requirement was that they study and become government bureaucrats.

To appease his mother, Alexander did postgraduate studies in mining and joined the Ministry of Mines. There he invented a safety lamp and started a mining school with his own money. But his heart screamed to explore the world. He was, he wrote, compelled by a restlessness as if chased by 10,000 pigs.

His long friendship with Germany’s greatest poet, Wolfgang Goethe, deeply affected his views. It changed him, he would recall, from being a scientist based purely on empirical and rational methods to one who believed in imagination and emotional responses. This, he said, equipped him “with new organs” through which to understand the natural world.

When his mother died, Humboldt immediately set off with Bonpland carrying permission from the Spanish king to explore his territories in South America. “The only profession that combines science, emotion and adventure,” he enthused, “is that of an explorer naturalist.”

Over five years they travelled through what is today Venezuela, Cuba, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico and briefly visited the US. Humboldt swam next to crocodiles, was nearly killed by a jaguar and paddled down rivers never before documented.

He came back to Paris in 1804 and was greeted as a hero. His boxes were full of notebooks, with hundreds of sketches, several thousands of observations on astronomy and geology and more than 60,000 botanical specimens. He brought back about 6,000 different species of plants, a third of which had never been studied or even seen before in Europe.

Humboldt set to writing the first of which would be many books, each of which would produce giant leaps forward in science. He noted how plants and animals “limit each other’s numbers”, something which would be confirmed only in the mid-20th century by the biologist and bio-geographer Ed Wilson. He warned of “mankind’s mischief… which disturbs nature’s order.”

He wrote lyrically rather than clinically, noting how leaves unfolded “to greet the rising sun like the morning song of birds”. Rainbows on Orinoco were “optical magic” that danced in a game of hide-and-seek. “What speaks to the soul,” he said, “escapes our measurements.”

His findings were to utterly change 19th-century science of the natural world.

Humboldt had an eidetic memory and was able, as he said, “to run through the chain of all phenomena in the world at the same time”. He saw plants, not as individual specimens, but as types according to location and climate.

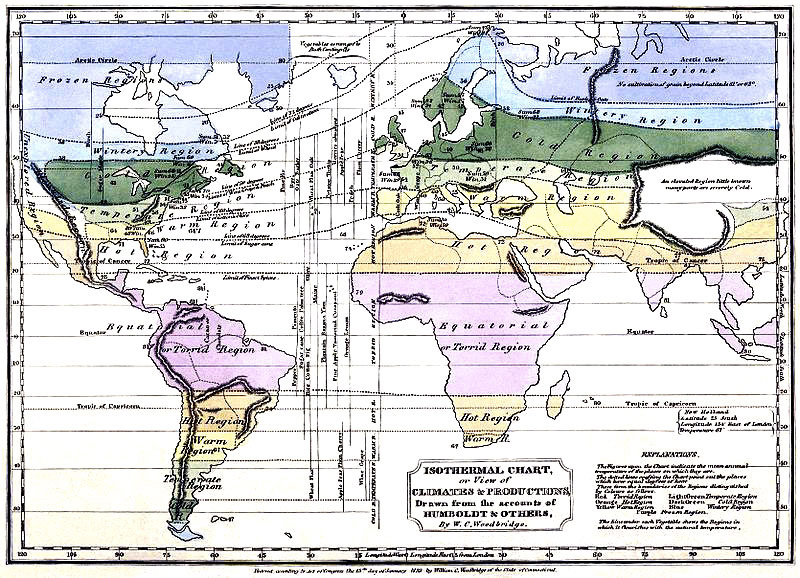

Noting threads of similar temperature across the globe, he invented isotherms, the lines of temperature and pressure we see today on modern maps. He also discovered the magnetic equator and provided the basis for our modern understanding of ecosystems.

He viewed everything, even the tiniest organism, in relation to everything else and part of a great chain of causes and effects. He wanted to understand how biological groupings change under the influence of altitude, climate and topography. “Rather than discovering new, isolated facts,” he wrote, “I preferred linking already known ones together.”

In Venezuela, he saw the devastating effects of forest cutback and warned of biodiversity collapse and the probability of human-induced climate change from the barren wasteland which reduced rainfall. He explained that forests generated rain and their destruction led to dry areas where soils washed away.

Meddling with the climate, he said, could have an unforeseeable impact on future generations. He listed the three ways in which the human species was doing this: deforestation, ruthless irrigation and the great masses of steam and gas produced in industrial centres. No one but Humboldt had looked at the relationship between humankind and nature in this way.

He was a man of contradictions. A fierce critic of colonialism and slavery, he supported revolutions in Latin America, yet was chamberlain to two Prussian kings. But above all, he shared his knowledge. He sponsored expeditions of young scientists from all nationalities and all disciplines – often with his own money. He wrote about 30,000 letters in German, French, Spanish and English and received many more than that.

During his long life, Humboldt travelled from the southernmost tip of South America to the eastern shores of Russia. He was an accomplished mathematician and was fascinated by scientific instruments. He measured, calculated, logged. But, for all that, he believed a great part of our response to the natural world should be based on our senses and emotions.

When other scientists of the time were searching for universal laws, Humboldt wrote that nature had first to be experienced through feelings. A whole section of his seminal work, Cosmos, is devoted to the literature, art and poetry of the natural world. He was that far ahead of his time.

His Views of Nature became an instant bestseller and was translated into 11 languages. The first volume Cosmos made him famous across the world: his publisher had never seen so many orders. It took readers from outer space to Earth, explored poetry, botany, biology, landscape painting, microscopic organisms, human migrations over time, vulcanism, geomagnetism and “the wonderful web of organic life”.

“External nature,” he wrote, “is that of unity in diversity and of connection, resemblance and order among created things most dissimilar in form – one fair harmonious whole.”

In a passage that could stand for the foundation stone of the future science of ecology, he writes:

“When we behold a plain bounded by the horizon and clothed by a uniform covering of any of the social plants; when we gaze on the sea where its waves, gently washing the shore, leave behind them long undulating lines of weeds; then, while the heart expands at the free aspects of nature, there is at the same time revealed to the mind an impression of the existence of comprehensive and permanent laws governing the phenomena of the universe… There is a chain of affinity binding together all nature.”

Fourteen years before Darwin’s path-breaking On the Origin of Species (and which would have been read by him) Cosmos laid out the foundation of the theory of evolution:

“The doctrine of evolution shows us how, in organic development, all that is formed is sketched out as it were beforehand, and how the tissues of both vegetable and animal matter are uniformly produced by the multiplication and transformation of cells.”

By the end of his life, he was an accomplished physician, geographer, historian, astronomer, ethnologist, mathematician, climatologist and volcanologist. He died in 1859 and was internationally mourned. A hundred years after his birth he was celebrated in the major capitals of the Western world with bunting, speeches and the unveiling of statues. The ocean current that runs up Chile was named after him, so were towns, rivers, mountains and universities.

But it’s fair to say that Humboldt’s revolutionary ideas are today unknown outside of academia and even then mentioned only in passing. However, though his legacy may not be obvious, it lives on in many forms. Charles Darwin said he would not have boarded the Beagle or conceived the Origin of Species without having read Humboldt. William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge used Humboldt’s ideas in their poems, Henry David Thoreau found in Humboldt’s books the inspiration for his brilliant tribute to wilderness, Walden.

The revolutionary Simón Bolívar, who liberated South America from the Spanish, called Humboldt “the discoverer of the New World”, and Goethe said an hour with Humboldt was the equivalent of eight days of reading books, spending a few days was like having lived several years.

Jules Verne used Humboldt’s descriptions in his books and his Captain Nemo, in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, had a complete set of Humboldt in his cabin. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring is based on Humboldt’s concept of interconnectedness. His ideas still speak to climate change, global biodiversity collapse and the spread of viruses like Covid 19.

Those were the sort of monuments Alexander von Humboldt would have approved of. His greatest legacy, however, is that he gave us our concept of nature itself. As Andrea Wulf noted in her compelling biography of Humboldt, The Invention of Nature, the irony is that his views have become so self-evident that we’ve largely forgotten the man behind them.

“It feels as if we’ve come full circle,” she writes. “Maybe now is the moment for us and for the environmental movement to reclaim Alexander von Humboldt as our hero.” DM/OBP

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Wow. Thank you.

Excellent article. I came across Hotel Humbolt at the top of El Avila National Park overlooking Caracas and the Caribbean. El Avila was known as the lungs of the city and the top was 2700m ASL. A suitable tribute to the man.

Hardly forgotten. Humboldt University in the centre of Berlin is a famous research institution which has produced over 50 Nobel Prize winners.

What a fascinating man Humboldt was. Thank you for this excellent article. I am happy to have discovered him.

He has been a hero of mine for many years. Thanks for bringing him back to life again in your excellent article.

I’ve been blown away by Andre Wolf’s biography, Invention of Nature, of this most extraordinary man….have just read it for the second time.