CARIBBEAN CONUNDRUMS

Cuba and Haiti: America’s troubled neighbours

The nations of Cuba and Haiti have long histories of interactions with the US, and generally without great success. What does history say to us? And what is next for those relationships?

Two Caribbean island nations — Cuba and Haiti — are both in the news, albeit for rather different reasons.

Aside from the difficult questions and choices the events in those two nations respectively pose for their inhabitants and rulers, they both may offer, even demand, very different challenges for American leadership, not least because their fates have been closely tied with America’s since their respective moments of independence from their former colonial masters. It is not as if the US can just walk away from engaging with either one of them. If nothing else, both nations represent pools of would-be emigrants eager to find a new home, and judging on history, that new home often seems to look more like South Florida or New York City than anywhere else.

First, though, some thoughts about the past. Back in 1969, leftist university students in America affiliated with the Students for Democratic Society movement who could come up with the scratch to pay for their transportation and upkeep, first started joining up with the “Venceremos Brigade” to travel to Cuba to work on the sugar cane harvest. This took place despite official US government disapproval and those travellers went by way of Mexico — then the usual arrangement — because of the US embargo already in place by then. As it turns out, we knew one of those students who, when she was asked what it had been like, after her return to school, summed it up by saying Cuba was glorious, but it was really hot.

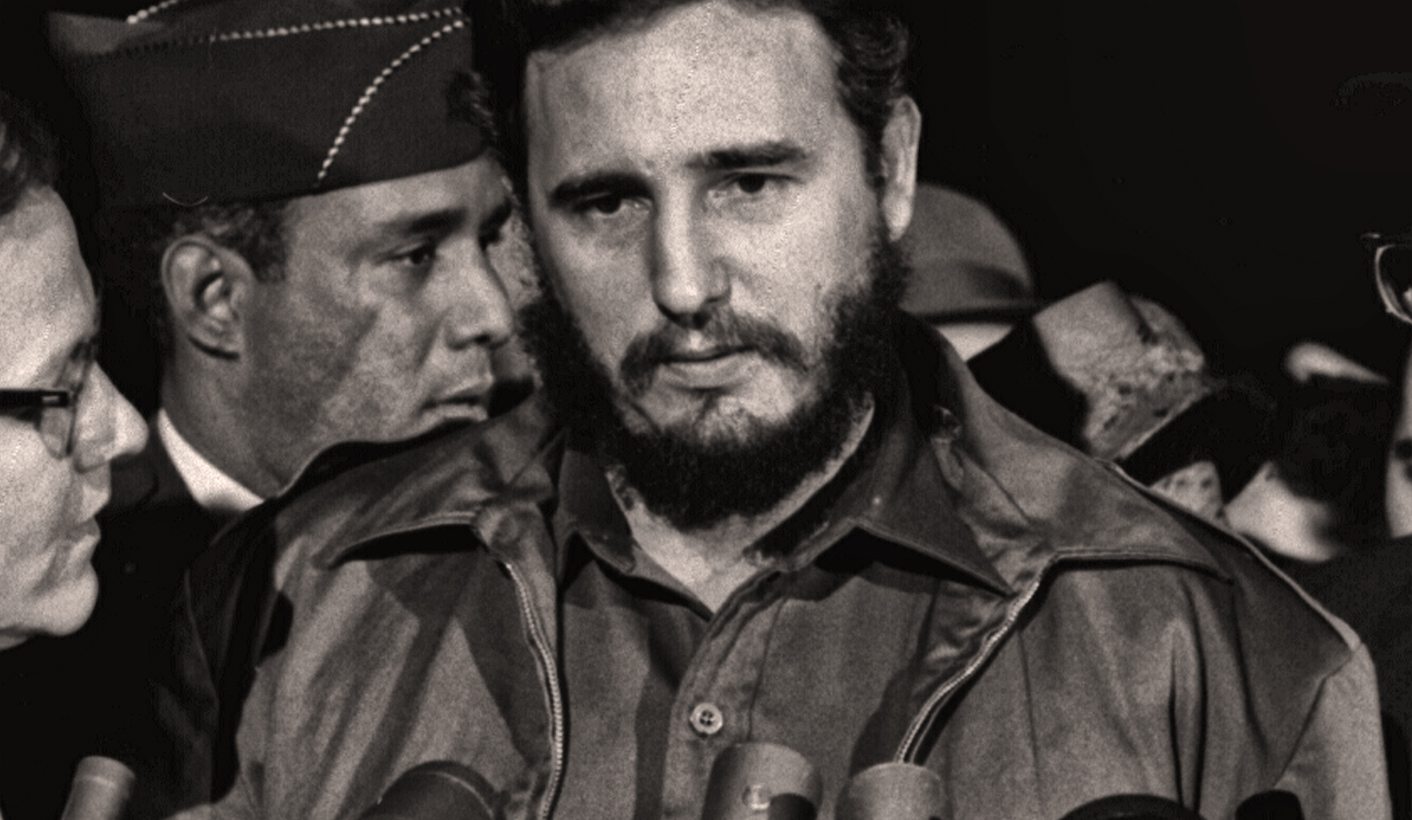

Fidel Castro. (Photo: Supplied)

Cuba, for many Americans, at least as far back as the late 1950s, was already high ground for international solidarity in the push-back against neo-colonialism. Then, when Fidel Castro and his guerrilla band, their beards, cigars, and fatigues rode into Santiago, and then Havana, and as the then-dictator, Fulgencio Batista, a man thoroughly in bed with the mafia, exploitive foreign and domestic business figures, and a number of American politicians, hurriedly departed over New Year’s Eve 1959-60, it seemed to so many that a new revolutionary age was dawning.

In an interesting footnote, remember Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Argentinian doctor and Castro acolyte whose thoroughly quixotic mission to lead another revolution, this time in the Bolivian Chaco wilds, ended in disaster and death. But his demise did little to dent his legend with young idealists or the heroic saga of Cuba for many, and it made him a pop star.

Even now, go to any T-shirt store in the world (I checked out in the store nearest my home) and there is Che’s face peering fiercely into the future he was certain he was about to make. Gracing sweatshirts, T-shirts and all kinds of other merchandise, his visage continues to give a boost to Che’s legend, the idea of revolution, and the pockets of T-shirt makers both. And, of course, every folk singer of the era worth their guitar had to be able to play that Cuban anthem, “Guantanamera”. (And for the older literary set, there was always Ernest Hemingway, sport fishing and living out his remaining days in Cuba — that is until he fled the new Cuba for Idaho.)

Of course, there are other Cubans that take up residence in the American mind. Fidel Castro’s revolution, as it moved forward, encouraged or drove thousands of middle- and upper-class Cubans to flee the country as their businesses, factories and family wealth was expropriated. (Fidel Castro’s pronouncement that he had long been a communist clearly did not help the country’s relationship with America during President Dwight Eisenhower’s last months in office either.) Most of the Cubans who settled in the US largely ended up in the southern part of Florida which was, after all, only 145km from Cuba and shared a similar climate.

On several later occasions, when the Cuban government chose to permit emigration to the US, thousands clambered aboard small boats, homemade rafts, and even the occasional inflated inner tube. Sensing an opportunity, the Cuban government also emptied prisons of those they deemed to be undesirables and sent them seaward to the US as well, that time becoming the influx of migrants dubbed the “Mariel boat people”.

Given the growing political heft of the Cuban-American population within the US, these latest arrivals were usually treated as political refugees, rather than just economic migrants, as might have been the case had they come overland across the Rio Grande River. Cubans have also enriched the ranks of professional baseball in the US (triggering a trade and immigration dispute) and a fierce rivalry between the two nations exists should they face each other in an international tourney.

Earlier, of course, back in 1961, there was the infamous Bay of Pigs — putatively secret — invasion. The idea, cooked up within the CIA at the end of the Eisenhower administration and sold to the new president, John Kennedy, as a surefire winner of a plan, had been to recruit an army from Cubans living in the US and then train them for a seaborne invasion of the island, with air support from some super-attenuated bombers, taking off from Central America.

The assault beach was the swampy Bay of Pigs on the southern flank of the island and, right from the first, things went awry. The planes failed to take off, supplies were lost, the element of surprise vanished quickly and the Cuban army’s resistance was far more effective than CIA planners had anticipated. By the end, nearly all the fighters had been rounded up or killed; the American official role in it all had been discovered and denounced heartily; and it took many months before the invaders could be repatriated back to the US to become a force of rigid opposition to any form of reconnection between Cuba and the US.

While the invasion failed completely in overthrowing the Castro regime, it did trigger a real sense on Castro’s part that a serious invasion by the US was now on the cards and he prevailed upon his sponsor, the Soviet Union, to station nuclear missiles on the island which could reach the US in a matter of a few minutes. There they could serve as a powerful response in the event of a second invasion. But it was a decision that in those American policymakers’ minds thoroughly unbalanced and destabilised the still-evolving nuclear standoff of MAD — mutually assured destruction — between the US and the Soviet Union.

Those missiles, discovered by American spy plane flights over Cuba in late 1962, set off the Cuban Missile Crisis that many believe had brought the globe closer to nuclear war than any previous Cold War confrontation — until the Soviet leadership blinked first. Ironically, it also led to the first limited nuclear test ban treaties as well as the withdrawal of the missiles. But it also confirmed in the minds of many American politicians that Cuba’s international behaviour would almost always be inimical to US interests — and vice versa.

A demonstrator during a protest march in Pretoria on 6 October 2006 looks at a Che Guevara T-shirt depicting a reproduction of the image by Alberto Korda. (Photo: Jon Hrusa / EPA)

As readers may recall, in the 1980s, in South Africa, many hailed the Cuban military engagement in the Angolan front fighting against the South African military as a form of international solidarity against repression or worse. The South African government — and America’s Reagan administration — saw this as proof of Cuba’s dangerous internationalist ambitions.

Throughout all that, the US embargo on Cuba continued, travel restrictions remained and it was largely until the Obama administration that a new approach became possible. Full — but tentative — diplomatic relations were restored and travel and trade efforts were made somewhat easier, along with funds for repatriations from Cuban Americans to their families and friends on the island.

Cruise ships began to make increasingly frequent stopovers in Cuba and officially sanctioned cultural exchanges even began. The Cuban government also began allowing the opening of privately owned businesses such as touring companies, hotels and restaurants, responding to the growth in tourism as well as the need to earn foreign exchange.

While Republican politicians have largely not joined the party, among many sectors of American society support for the still further loosening of embargo restrictions has continued to grow.

Agricultural commodity sellers and producers look eagerly at Cuba’s market. And the vice grip on US Cuba policy that has been held by an older generation of Cuban Americans has weakened with the passage of time. Moreover, younger Cuban Americans have increasingly come to support a US-Cuba relations reset. While that was halted under the previous US administration, such a shift may come again under the new Democratic president.

Nevertheless, representative of the older viewpoint of influential Cuban Americans, Florida and Texas Republican Senators Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz remain largely opposed to greater openings to Cuba and their voices are very strong on such positions, so a reset may only take incremental steps.

Of course, the two countries’ fates were intertwined before these more recent events. Following American independence, there were already ideas about liberating Cuba from its sclerotic, ineffectual Spanish colonial regime as the Spanish colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere crumbled. (Counterfactual historians have fun writing about a Southern victory in the Civil War and the conquest of Cuba by the South instead of the American purchase of Alaska in 1867.) In the real world, the local Cuban revolt against Spain from the 1870s onward captured American attention and even freelance war correspondents like the young writer Stephen Crane went there to cover the fighting.

The explosion of the US warship, the USS Maine, while on a port visit in 1898, became the proximate cause for a declaration of war against Spain and rather easy victories in the Spanish colonies of the Philippines and Cuba. Not too surprisingly, Cubans felt they had been fighting for years for their own independence which was only reluctantly confirmed several years later, but with the granting of a permanent naval lease for the US at Guantanamo, and a provision in the Cuban constitution that allowed considerable scope for US intervention in the island’s financial affairs. That brought the US-Cuban relationship pretty much up to where it was during the Batista regime.

Now, of course, there have been those large, generally spontaneous mass protests by ordinary Cubans all around the island aided by the use of social media. These demonstrators say they have been driven to anguish and frustration by growing shortages of food, fuel, energy, and even potable water. These problems have been exacerbated by the Covid pandemic that has caused a precipitous decline in tourism, devastating the earnings of many working in small businesses in the tourism and hospitality sectors.

At about the same time, a rise in racial tension on the island between Afro-Cubans and a more mixed race other half of the population (including the country’s elites), as well as a new assertiveness on the part of the former and anger they have not received their fair share of things also may further shake the foundations of the Cuban government. This is a government that is being led for the first time since 1960 by someone whose last name is not Castro — Miguel Diaz-Canel.

How the Biden administration should — or can — respond to all of this beyond expressions of public support for Cubans’ desires for greater freedoms is a challenge. So far, this has been one in which the US government seems, so far at least, unable to define a policy that in a way answers all the sectors claiming to have or wanting a hand in shaping Cuba policy. And, in fact, its actual tools for influence remain limited, mostly being in the form of the carrots of loosening restrictions on trade, travel, and financial transactions, when each of those could well be seen as victories for the Cuban government in its own domestic pronouncements.

On Thursday, the Biden administration tried to sort out a first response with economic sanctions on a select body of Cuban officials. As The Washington Post reported, “The Biden administration will announce new sanctions Thursday against a number of Cuban officials deemed directly involved in human rights abuses during a government crackdown on widespread protests earlier this month, a senior administration official said. The sanctions will initially affect what officials said were a small number of individuals from Cuba’s Interior Ministry and military forces. The measures come as President Biden is under increasing pressure from Congress, activist groups and Cuban Americans to take decisive action in support of the protesters.” That clearly is not a final answer.

The next island to the east is Hispaniola, and the western third of it is the desperate nation of Haiti. Buffeted in recent years by earthquakes, hurricanes, appalling governance, routine kleptocracy, and deeply entrenched poverty, Haiti is now undergoing yet another crisis in mis-government, this time by the assassination of its president by a group of thugs apparently recruited from among disgruntled Haitian-Americans.

Curiously, the numbers of Haitian- and Cuban-Americans in the US are roughly about the same, but the two communities have startlingly different political weights. Haitian-Americans are largely clustered in cities in the Northeast but have much less political heft than the Cuban-Americans, with virtually no public office holders among them. There are lots of popular musicians who claim Haitian ancestors, but that is not quite the same as political heft.

But like with Cuba, ties between America and Haiti also go back to the initial years of the US as an independent nation. In the 1700s, once it had been wrested from Spain, Haiti had been the jewel in the new French colonial empire. Built on the growing of sugar cane for sugar to meet the insatiable demand in Europe for this cheap sweetener, Haiti had become the world’s largest sugar producer and thus the most valuable of France’s possessions. When the French lost Canada and the Mississippi Valley to Britain and Spain after 1763, they still fought tenaciously to keep their hold on Haiti.

Haiti’s economy, of course, was almost entirely based on slavery of Africans forcibly brought to the island, the aboriginal inhabitants having largely died out or been killed. In the immediate aftermath (and influence) of the ideals of the French Revolution and the American one as well, Haiti’s slaves revolted against their oppressors. Many of the whites who had not died during the fighting emigrated to Louisiana and elsewhere, and, finally, by 1802, the former slaves had secured their independence.

They eventually defeated a crack French army that had been sent there to suppress the rebellion, although that defeat was aided by the endemic disease of yellow fever that killed thousands of French soldiers. What this defeat also did, however, was to convince Napoleon to sell French rights to the entire Louisiana Territory, right up through to Minnesota, to the new nation of America, territory France had regained from Spain just before. That purchase doubled the size of the United States, giving politicians and editorial writers the first real taste of the idea of a continental-sized nation, eventually reaching the Pacific Ocean.

Sadly, in the ensuing years, Haiti never actually gained stable, solid governments or much in the way of economic growth. Its forests were stripped of trees to make charcoal and its economy was routinely looted by politicians and friends. (A satellite photo of the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, its neighbour on the island, shows the sharp demarcation between the eroded, denuded land on the Haitian side and still lush forests on the other.)

Eventually, the US sent a force of Marines to run the place for several decades, and upon their departure, Haiti’s longest-serving despot, François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, took over the presidency and the looting. After his death, Haiti reverted back to older, unstable ways with a roster of short-lived administrations, amid the hurricane and earthquake damage — and the continuing departure of pretty much anybody who could leave to make a better life elsewhere, especially creating a Haitian diaspora in America. (Of course, Haiti also had to contend with a long-running debt to France over the cost of slaves liberated from the masters, but we can let the French respond to that.)

Over the years, Haiti has received foreign aid and the presence of experts from many sources, but seemingly without achieving much real progress amid the human and natural carnage. (We had friends who went there in an international medical aid team, and they were brutally killed as “collateral damage” amid a local dispute between rival gangs where they were working. Too much of Haiti’s history seems to be encapsulated in Graham Greene’s novel, The Comedians, or the film made from it, where pointless death and fighting seem omnipresent.)

Here again, the Biden administration is also facing choices, virtually all unpalatable.

Is it possible to bring Haiti on to a different economic trajectory and the creation of a semblance of political stability, but without a massive intervention that has never really worked out there previously?

Or, should the Biden administration elect to encourage other actors — but who might that be? — to take the lead in this newest version of a “Mission Impossible” of nation building — especially since the Biden administration has just explicitly ruled out nation building as an approach, at least for Afghanistan, but presumably applicable elsewhere?

The challenge, then, is to find some way and some coalition of partners that can improve the lot of Haitians, at least incrementally, rather than needing to prepare for waves of Haitian boat people heading towards South Florida, or drowning in the attempt. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.