OP-ED

July 2021 Zumite sedition and the emerging ‘politics of the mall’

While the politicians debate whether recent unrest in KZN and Gauteng amounted to a ‘failed insurrection’, and the ‘commentariat’ sagely pontificates, what has been missed is the most obvious — the emerging ‘politics of the mall’.

If we have one thing in common, it is the fact that we are all “mall rats” now. Sure, the few spend a lot, while the rest wish they could spend something. But what we all need can now be found at the local mall.

Surely we now need to ask the question: “why malls?” And surely that will provide a more significant material basis for debating the significance of these events than the political tropes derived from outdated largely Western theories of revolutionary change that we use as lenses for making sense of our complexified context.

There is near complete consensus among those who think about our economy that since 1994, two particularly important inter-linked dynamics have shaped our economic development trajectory — namely, consumerisation and financialisation. As the manufacturing sector has gone into decline, economic growth has been driven largely by consumption (consumers who buy more stuff).

That, however, would not have been possible if consumers did not have money. If the numbers of employed people are not rising, where does the money come from for all these increases in consumption? The answer is debt. Without massively expanding the amount of debt available to the expanding, increasingly multiracial middle class, the consumption-driven growth we have seen since 1994 would not have been possible. This, in turn, explains why the economy financialised.

Financialisation takes place when finance rather than primary production (mining, agriculture, etc) and manufacturing makes the biggest contribution to GDP growth. Unfortunately, services and finance-driven growth are not job-creating growth. Nor do they facilitate wealth redistribution — indeed, leaving existing land and property ownership intact is essential for the securitisation of the extended debt portfolios. Hence our so-called triple challenge — the persistence of poverty, unemployment and inequality.

At the core of South Africa’s Biggest Looting Campaign — better known as State Capture — was a political project to redirect the rents generated from financialisation and consumerisation into the hands of a political elite that felt excluded from the centres of financial power. Brian Molefe made that very clear during his remarkable testimony at the Zondo Commission about setting up a new bank for black capital; and the Gupta-compiled cheat sheet that Des van Rooyen was given just prior to his “weekend special” tenure as minister of finance included setting up a new state-owned national bank. And don’t forget the hoo-ha about the Reserve Bank’s so-called independence that our current Public Protector instigated.

What began as financialisation and consumerisation after 1994 became grand-scale looting during the State Capture years as the Zupta-centred power elite became impatient with “White Monopoly Capital”. When no one went to jail, everyone else was entitled to assume that looting is the South African way. (And now we debate whether this is insurrectionary… but I run ahead of myself.)

What needs to be recognised is that consumerisation and financialisation depended on the total spatial restructuring of consumption within South Africa’s urban centres. This was achieved by explicitly proliferating the construction of malls (many funded by the Public Investment Corporation) and concentrating the location of the supermarkets within these malls (funded mainly by private banks). The result was what UCT researcher Jane Battersby calls the “mallification” and “supermarketisation” of consumption.

Following the research by Battersby, just before the democratic era began, in 1992 less than 10% of all food was sold via the large supermarket chains in South Africa. The neighbourhood shops (the corner “caffee” and veg shop) and informal sector are where we bought most of our food in 1994. Only 10 years later, 60% of our food was supplied via the supermarkets. By 2010, 68% of all food was sold via the supermarkets (the highest in the world) and by 2017 75% of all groceries were sold via the supermarkets — the rest was distributed via the informal sector. However, without “mallification” this would not have been possible.

Retail space in 1970 was only 207,000m². However, as Battersby’s research shows, by 2002 it was more than five million square metres, and by 2010 a staggering 18.5 million square metres of retail space had been constructed. The proliferation of shopping centres after 1994 resulted in 1,053 by 2007, and then nearly doubling to 1,942 by 2015.

For those who think this was demand-led via the market, think again: total numbers dropped from 45,489 people per mall in 2007 to 28,321 in 2015. Overproduction because of easy access to finance has resulted in increasing amounts of empty space in malls. South Africa is fifth in the world when it comes to numbers of shopping centres. Shopping centres occur mainly in urban centres on land that needs to be zoned for this purpose by local government.

Even though local governments have no powers to determine the supply of food, by actively promoting mallification and supermarketisation, they have inadvertently been the primary drivers of restructuring food distribution to the majority of South Africans since 1994. And this has become synonymous in the minds of local politicians with “local economic development” (and more recently “township economic development”) — I recall the deputy mayor of Stellenbosch once saying to me: “How can we have development in this town without a mall?” Now we have two, and Stellenbosch is more unequal than ever.

Malls and supermarkets were the spatial fix that was needed to make consumerisation and financialisation work. They were also needed to reinforce the phantasmagorical consumer culture that has become the secular religion of the new debt-ridden, car-based, multiracial middle class that loves to “drive to park-n-shop”. But it was also needed to herd the urban poor (employed or not) into the proliferating “township malls” (promoted by local governments as “local economic development”).

The dramatic increase in the payment of social grants to 17 million South Africans created a consumer spend of R150-billion per annum. Christo Wiese may present himself as “bringing retail services to the poor”, but it was the social grants financed by the taxpayer that he cleverly raked into his gigantic treasure chest (which he later realised he needed to share by enriching his BEE partners).

Consumers needed to be herded into tightly controlled spaces to buy stuff from increasingly concentrated retail chains financed by powerful public and private financial institutions. The Public Investment Corporation (PIC), a public entity that invests government pension money, led the finance group that funded mallification, and the private banks funded supermarketisation. Centralised retail chains in centralised malls suited a centralised financial system. The neighbourhood shops (which used to be key donors for local civil society groups) went into decline and with them a key economic mainstay of community life. In short, consumerisation and financialisation led to mallification and supermarketisation which, in turn, has ripped the social guts out of local communities.

So the next question is whether these malls are, in fact, the engines of local economic development that developers, financial institutions and local politicians make them out to be. A remarkable Facebook post by Djo BaNkuna from Pretoria entitled The Dark Side of the Current Mall regime is worth quoting in full on this topic:

“A Mall is NOT development. Township Malls are instruments of poverty and exploitation. The sole purpose of a Mall is to permanently extract liquidity in the community ecosystem to the rich suburbs and offshore accounts. Once a Rand enters a Mall, that community will never see that money circulating in that community again. A Mall is like a fishnet, once the fish enters, it will never see the ocean again. Communities are poor because they do not have enough money in circulation. Shoprite shall never buy magwinya from Mrs Zulu, second tyres from Thabo or hire a cleaning company from Soshanguve. Mall money only travels in one direction from the community to the Mall, from the Mall to their wealth owners away from the township.

“One of the biggest mistake government is making is to continue to allow the proliferation of Malls in their current format. Members of the community do not have an emotional connection to the mall. For many, each visit to the Mall is like a visit to the zoo where they observe what they can never own. The Current Mall regime treat community customers as visitors than collaborators. They do not know who owns the mall, who sells in the Mall and who made the products being sold in the Mall. The Mall’s presence in the township is limited exclusively towards extracting value in the form of money. That is why Malls are seen as an external creation than a true part of the community (maybe with the exception of Maponya Mall).

“So, our celebration of the building and opening of a Mall is myopic, ill-educated and misguided. The celebration demonstrates how poor our comprehension and understanding of the basics of labour exploitation and profit making.

“What must be done? Introduce a policy on 70% local for certain goods/merchandise, force Malls to set aside 30% of floor space for local business. Restrict big cartel anchors like Checkers/Shoprite to one shop per mall per 20km radius. Do something! It is more complicated, but that is a start. Until then, just like cattle, we are grazers and consumers of the worst kind. We are producers of dung. As you know, cows end up in the slaughterhouse. We are busy celebrating our ignorance.”

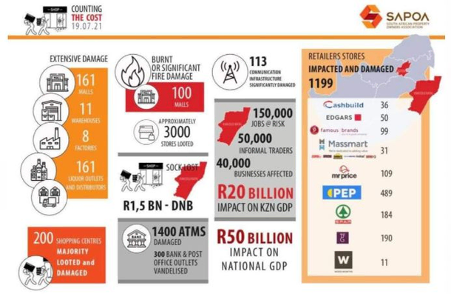

According to the SA Property Owners Association, 161 malls were intensively damaged, 100 burnt and more than 1,000 retail stores damaged, with Pep, Game, Spar and Mr Price the most targeted. (So much for the argument this was a food riot! People need clothes.)

So, we return to the question of how best to characterise what happened during that fateful week after Jacob Zuma was imprisoned. Those who argue that it is problematic to characterise the events as an insurrection have a point. An insurrection implies an orchestrated act of violence aimed at collapsing or overthrowing a state. Some of the tweeters may have used this rhetoric, but there is no evidence that the logistics were in place to execute such a plan.

There is more than enough evidence, however, that there was in fact a group of instigators with a political strategy who triggered mass looting by sabotaging key high visibility targets with the explicit purpose of subsequently broadcasting these acts via social media. Then, following the wildfire analogy, the looting spread uncontrollably as a conglomeration of people who did not have an explicit political agenda (criminals, petty opportunists in their Mercs and SUVs, and a large number of desperate people who just took the gap and made good) seized the opportunity of a dazed (and probably divided) security establishment to attack the malls.

Sedition, therefore, best describes what the instigators had in mind. Sedition is organised action aimed at calling for or catalysing violent acts against the state to achieve a political objective. This may intentionally or unintentionally catalyse an insurrection or even a coup d’état, but this may not have been the original explicit intention. Sedition could also be an assassination or sabotage of infrastructure to secure a concession.

In short, what started as an act of sedition to secure Zuma’s release, triggered waves of mass looting of malls by many whose intentions were primarily acquisitive. But this then begs the question: why malls? Don’t get me wrong: I am not suggesting the attackers of malls understood that malls have become the epicentre of a failed post-1994 economic development strategy that has resulted in the persistence of poverty, unemployment and inequality. No.

Malls were attacked because they have become the epicentre of everyday economic life in post-apartheid South Africa — it was not factories that were attacked, as often happens in industrialised societies (because we did not build them). Malls are, quite simply, where the stuff of everyday consuming is now located. And as Djo BaNkuna put it, “the community do not have an emotional connection to the mall”.

That may change now, because the politics of either looting or protecting our local mall has now become the epicentre of middle-class politics. That does not mean working-class people are not at the barricades of protection. But in the final analysis, the sedition failed because the mall-centred consuming middle class felt attacked. Who would have thought back in 1994 after buying bread at the local “caffee” that by 2021 community organising would be about protecting the malls, complete with T-shirts boasting #no looting in my town?

What the July 2021 “Zumite sedition” and subsequent mall looting should signal for us all is the end of an economic development strategy premised on debt-financed consumerism that was spatially fixed through twinned strategies of supermarketisation and mallification.

To think these grocery fortresses (that need protecting now by police and army) surrounded by masses of poverty-stricken people in the most unequal society in the world can continue as lodestars of local economic development is a form of extreme stupidity. It is now, also, a security risk.

The solution lies in redirecting financial resources into the “real economy”, with a focus on production. We also need to rebuild the local neighbourhood retail centres and corner shops. We should have done this long ago, but as Djo BaNkuna proposes, it might not be too late. The PIC could take the lead by refusing to fund the next mall. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Spot on. The big supermarkets control the food chain while mall owners control public spatial planning. They can do as they like. The very heart of the ‘Far South’ which should have been the urban centre, but is designated in planning terms as a ‘node,’ is in reality a parking lot with two malls.

Thanks Mark, a fascinating analysis. My impression however, is that the violence was more orchestrated than you are allowing for.

Fascinating explication and analysis, thanks

This is the kind of essay I want to read in the DM – counter-intuitive and thought-inducing – to help me make sense of the world we live in today. I read and was very impressed by that post by Djo BaNkuna and shared it, to mixed response.

Malls are destroying our inner cities, by drawing people to it, and away from the high street. The result is a something like an ‘anti-gentrification’ (some might say liberation) of what used to be the main business district of a city or town. Companies headquartered in the city soon follow, leaving entire office blocks vacant. Landlords drop their standards, and rent to people who might work there, but also live there. This vacuum is further filled by criminal activities like drugs and prostitution, which drives most restaurants away, resulting in less people on the street at night, and more illegal activity. Ironically small grocery stores also return, owned by Somalis and Pakistanis, to serve the new clientele that have replaced the shopping middle class. City planners are very much complicit in this trend, because they allow and even push for mega malls like V&A Waterfront and Century City. This trend has even more impact in our medium-sized towns like Worcester. Even a small town like Caledon now brags with a mall. Meanwhile the municipalities neglect their high streets, rife with potholes, blocked drains and uncollected rubbish. The character of the town changes, and the money heads for the mall, just like Djo says.

Hmmm…. what sprang to mind as i read your comment – is this a convenient way for an inept local authority to pass the buck? If the middle class are inhabiting the malls which are maintained privately, does it take attention away from neglected town centres?

White Monopoly Capitalism must look in the mirror and finally take responsibility make amends. SA CEOs are among the highest paid in the world. Allow and support politics to make required laws for justice. Remember ‘trickle down’ does not work.

Fascinating dissection of the “shopping mall” in the context of spatial apartheid and ownership. Thought provoking, thanks.

Excellent article, a different lens through which we can view the actions in KZN and Gauteng and be far more critical of “development” in our cities and who really benefits.

Great article Mark. This is the kind of input that is sorely needed by a host of decision makers ranging from politicians to banks, investors with a sense of morality, and city and town planners. To expose the general public to these trends is also much needed to develop an understanding of the world around us.

Exceptional article. The same principle applies to national chains in small towns. Fast food chains at service stations etc, PEP and mini supermarkets take all the money that was circulating in small towns out of the small towns. Previously local entrepreneurs made the profit and circulated much of it in the towns but in respect of fast food chains, money from the passing trade is just shipped out of the town as soon as it is spent. When one drives through these towns, the locals are just wandering around the main road doing nothing because there is nothing to do. Its a tragedy and a contributing factor to migration to the cities.

We seem to be losing sight of the employment opportunities provide by local malls, and the recirculation of the wages paid (however meagre), back into local communities.

Secondly, local malls in townships have enabled people to shop locally, and save on the high transport costs in travelling from say, Soweto to Johannesburg to do their basic shopping, as in pre-mall times.

I would also posit that the large chains, with their economies of scale, have brought lower prices to local shopping malls, especially in foodstuffs and basic clothing.

Insightful and on the money. Been watching and worrying about Mall proliferation for 10 years now, thinking it was driven by life insurance companies funding balance sheet assets to house their loot. Congratulations. Interesting how so much commentary and focus is (correctly) on corrupt politicians, but not much on the deeply corrupted, power and money hungry corporates who feed this not so subtle looting. Until we shift that system, we (in fact the world) are doomed to continue plundering, leveraging and destroying our resources for self and shareholder gains.

Professor Swilling is way off the mark here. Supermarkets are an enormous benefit to the poor. They bring an enormous variety of essential goods at the best prices to a poor community in an efficient way. They are the anchor tenants of malls which can then support smaller specialist shops all in one location. That an academic being paid with taxpayers money can think and preach that the destruction of supermarkets and malls in poor areas will be beneficial to those communities by forcing them to rely on “local” shops selling a smaller variety of more expensive essential goods is deplorable.

I think the real issue is that they don’t recirculate as much wealth in the community as locally owned businesses would. In other words, fewer of the poor will stay as poor, and in time will be able to afford more.

Supermarkets operate on thin margins and deliver value for money to the comsumer. That’s what matters most to the consumer. Small shops requiring higher margins are not the answer for a poor community.

Three points in response to Mr. Young: 1. What about the argument that mall shopping is extractive in that money goes in but doesn’t circulate back into the community? (Even mall salaries from jobs they provide don’t do that if they’re then spent in the mall.) 2. Please show us where the author says or implies that “the destruction of supermarkets and malls in poor areas will be beneficial to those communities.” If their non-existence is (controversially) a benefit to poor areas, it (uncontroversially) doesn’t follow that their *destruction* is a benefit. Nor does Swilling suggest otherwise. 3. Is “an academic being paid with taxpayers money” meant to have certain views? Is Mr Young really suggesting we follow the Chinese or Soviet models of “academic freedom?”

1.So you should treat your community, however that is defined, as an island and make and sell everything within the boundaries of that community. This then leads to wealth and prosperity within that community. What nonsense. This is called mercantilism and has been discredited centuries ago.

2. You cannot just ignore the context of what has just happened to malls in poor communities.

3. Yes an academic can and should hold whatever views he likes but he is also subject to criticism and ridicule for what he says. I don’t know how you inferred that I propose censorship. I do not.

1. I was asking a question, not taking a position. If Swilling’s idea is nonsense, it’s his nonsense, not mine. I did think it was interesting, though, and was curious what Mr. Young’s response to it is. I guess we now know, though it strikes me as a caricature of his argument, not his argument.

2. Mr. Young doesn’t come close to answering my request. He attributes this to Swilling: “the destruction of supermarkets and malls in poor areas will be beneficial to those communities.” My question was where and how Swilling suggests that. The correct answer is that he does not, so here again we have a straw man.

3. Mr. Young says this: “That an academic being paid with taxpayers money can think and preach [insert deplorable view here] is deplorable.” This suggests that such academics have a responsibility to think and preach certain things and not others (from which it does *not* follow that censorship is justified). Mr. Swilling’s view apparently fails that test. Hence it is deplorable. But this makes a complete mockery of academic freedom. Of course such views are open to criticism (though ridicule is best left to the school playground). But not because they come from an academic being paid with taxpayers’ money. All that is just an unhelpful red-herring.

1. I answered your question. The notion that economic activity should be confined or maximised within your local community is nonsense and that if money goes out of your community it is “extractive” (your term) is also nonsense. The very computer or smartphone you used to make your comments was not and cannot be made in your local community. In buying this device you allowed an “extractive” transaction to take place. 2. Take a look at the image associated with this article showing the Alex Mall which was destroyed by looters. Prof Swilling is implying that this might be good for the community of Alex. I beg to differ. 3. Academics can say what they like. However if they say that economic activity should be confined to their local community and poor consumers should pay more for food in order to keep money within the boundaries of their local community then I suggest that taxpayers’ money is being wasted on this academic’s salary. Academic freedom does allow academics to espouse ridiculous and harmful views and at some point this is wasteful.

Mark’s argument is founded on an understanding of “circuits of capital.” Value circulates through economic systems in various forms, including labour and capital. When ownership of capital is primarily local, it leads to reinvestment within that local circuit of capital. When ownership of capital is externalized, i.e. when local circuits of capital are incorporated into larger ones, the disposition of capital is no longer subject to local decisions. That’s why in the end Mark’s policy recommendation is for the state to intervene to regulate how capital generated in Township malls and supermarkets is distributed. Left to the free market, it will leave those local areas and be invested elsewhere.

On the other hand, Mr. Young is stuck in an ideological cul-de-sac. He has no understanding of where wages come from, or how the pattern of investment of capital determines where wages grow and where they shrink. Instead, like the right-wing competition theorist Robert Bork, whose ideas have helped to destroy the U.S. economy and bring about political collapse, he only understands prices, not value. Sure, products at a ShopRite may be cheaper than those than a spaza, but focusing on that variable only inevitably leads to the impoverishment of local economies … and thus, to the looting of malls.

Excellent articel. Makes a lot of sense to me! These same for applies for David Gant. Maybe another Codesa, but soonest, will assist the weak government to put through meaningful reforms.

Very important contribution Mark. Thank you.

Will the likely increase in online buying increase consumerisation and financialisation further?

Setting aside sedition vs counter revolution vs insurrection – because I think it was a mix of all three – I buy your basic argument about malls and consumerism and the changed nature of capitalism and consumerism, but also find this (forgive me) somewhat reductionist. Only in the sense that this last 10 days had multiple criss-crossing elements – looting of malls by the poor and excluded was the Steve Bannon ‘dead dog’ trick – throw a dead dog on a table, everyone runs around screaming, no-one stops to ask – who threw the dog? So how were malls so professionally opened (to allow looting)? Why did security cameras go, immediately; followed by their recordings; followed by the back-ups of their recordings? Could it be that a pretty sophisticated criminal game was at hand, for which looters were a very useful screen while weapons and high end goods were being stolen, loaded up and taken away? And if malls were the sum total of the problem, why were cell-phone towers attacked, along with reservoirs and sub-stations? That isn’t sedition, I’m afraid. None of this contradicts your arguments about malls – but the argument about malls doesn’t fully explain why happened for the last 10 days.

I am sure that the widely published extravagant remuneration of CEO’s of Shoprite, Pick & Pay and others was a contributing factor. They are the face of their businesses, therefore the indirect targets of those whose daily lives are a struggle for survival.

Just last year PnP dropped exclusivity contracts at malls where they are tenants. Maybe it needed to happen 20 years earlier. A small step but one in the right direction.

I say the following in the knowledge that globally, the tide is already turning against malls, but I am unclear as to where it is leading us. Malls have their cons as listed, and their pros. However, at a higher level, they are Efficient. If your system is capitalism, and your capital is seeking a good return, this is where we have got to. It is just that the production and logistics is further afield than the local community. Amazon is another example of efficiency, capitalist style. Of course money is power, and too much is concentrated in the few, and there is also monopoly formation, but this is the nature of constructive destruction. We cannot squeeze the toothpaste back into the tube, nor should we want to. Having that powerful innovation system, it is up to government and society to harness the power for everyone’s good.

Thank you Mark for a most helpful analysis. Something has to change about the way we move forward as a country. Whether it’s the malls or not clearly we can not continue as before.

This was super interesting. I agree with David Everatt thought that it doesn’t adequately address the more organised elements of the upheavals, like the looting of 1000 000 bullets from the Mobeni warehouses, or the Mail & Guardian’s seemingly well-substantiated suggestions that this was possibly intended as just the first stage of something bigger. Also, although the analysis of the economic and community effects of malls was very enlightening, if you say that the people who did the looting don’t understand that, then how does this explain why they chose malls to loot? By saying ‘Malls were attacked because they have become the epicentre of everyday economic life in post-apartheid South Africa…Malls are, quite simply, where the stuff of everyday consuming is now located. And as Djo BaNkuna put it, “the community do not have an emotional connection to the mall'”. – do you mean people just went to wherever the could get stuff, and didn’t feel bad because they had no connection to the place? Ok, well, people also looted non-mall shops, warehouses, petrol stations, etc. Very small towns in KZN that don’t have malls were also decimated. So then?

Mark, it would be interesting to study the intersection of financial capital and development finance/urban planning in India, where the state has recognised the importance of preserving small-scale local commerce. What accounts for the different trajectories? What are the institutional differences?