NATURAL WORLD

A delight in backwater kayaking

There’s just something about a kayak and a wild stretch of water that makes life worth living.

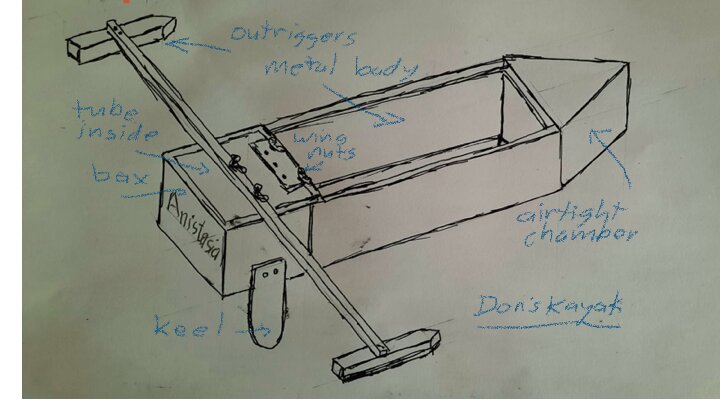

When I was about 10 my father acceded to my persistent pleas for a canoe. Not living in a place where such things could be bought, he had a friend solder up a sort of galvanised box with a flat bottom and pointed front.

We tried it but it shipped water at the rear. So we added an enclosed whisky crate at the stern containing an inflated car inner tube. That held it up behind, but with a flat bottom it was unstable, so my dad attached – with wing nuts – a beam ending in outrigger floats made from two pieces of roof truss.

Each addition required a trip to the nearby Bongolo Dam with the contraption tied to the roof rack. The end result was not pretty, though it looked rather like the spaceship Anastasia from my favourite Dan Dare comic. I was well pleased.

Being by now heavy and too unwieldy for constant transport, we hauled it to the inlet end of the dam and hid it among the swampland and riverine forest in a place only we knew. I would be dropped there on Sunday mornings and, quite alone, make my way along a secret path carrying my paddles made from circles of floorboard on a broomstick and a lunch tin containing tomato and cheese sandwiches and a Coke.

Don’s kayak. Image: Don Pinnock

I’d drag my canoe into the water and push off into the mysterious swampy wetland. The silence was both scary and delicious, broken by the occasional calls of laughing doves or the sudden flurry of wings when I disturbed a roosting cormorant, little egret or frog-hunting grey heron.

It was during these quiet paddles, or sitting on a fallen tree munching my sandwiches, that a delight in backwaters was born. I remember a thunderstorm brewing over the distant mountains one March. Both air and water were perfectly still under an overcast sky – mid-afternoon had all the serenity of evening. A giant kingfisher’s kek-kek-kek seemed to echo from shore to shore.

The dam was as smooth as a mirror and the clear portion of the air above it seemed shallow and darkened by clouds. The water, full of light and reflections, was a lower sky itself and so much more compelling. I sat, spellbound, and only when lightning drilled into a nearby hill did I remember that I was in a metal canoe.

Years later, driven by my backwater passion, I was in a kayak on the Palmiet River facing what seemed a more immediate danger than lightning.

Good winter rains had fallen the week before and that night it would snow. One can become lyrical about the beauty of the scenery around Kleinmond, but right then the Palmiet River was simply a ditch sluicing countless tons of water off the mountainside.

The tea-brown stuff was being whipped into an ugly froth, hurtling over, round and under obstacles, going left, right, downstream and even upstream, forming high-speed vees, holes, strainers, rooster tails, standing waves, surges, pillow waves, eddies, aerated bubble banks and nasty barrel rolls known, appropriately, as washing machines. I was heading for a gargling vortex which kayakers call a hole.

Earlier, we’d been coaxed and chivvied by our guide to do things he thought would be necessary to stay alive while hurtling downstream. He’d kicked off with a nice little lecture on the various ways we’d be likely to die.

So when I hit the water I was filled with images of smashed shin bones, dead kayakers held underwater by “strainer” branches and – after viewing some photos of lifeless human flotsam – an almost hysterical fear of weirs. But what kept me awake the night before was ravenous holes.

A hole is essentially a whirlpool laid out on its side, with its axis of rotation perpendicular to the main current. It’s a cylinder of water and froth that recirculates constantly in position, like one of those giant spinning brushes in a car wash. For a good approximation of how it feels to drop into one, you could take a pass through a car wash on your bicycle.

Holes, according to an authority on the subject named William Nealy, have to do with vortical hydraulics. The velocity of water dropping over an obstacle is far greater than the water velocity below the hole. This creates an excess of piled water with nowhere to go. Gravity pulls some of it upstream and the water rolls under, down through the hole again, driving the cycle even further.

Experienced white-water kayakers drop into holes on purpose, using their precarious equilibrium for blatant shows of hotdoggery. A novice sucked into a sticky hole does a brief ballet of catastrophe and disappears into the maw. You have an emergency.

River kayaks were once long, narrow tubes of fibreglass. These days they’re spoon-nosed, spoon-tailed, flat plastic creatures that have more in common with propellers than things in which Inuits chase seals. There’s a good reason for this.

Drop a Pyranha, Perception or Dagger into a hole and its nose will go down like a shovel, its tail will go skywards and you’re in an ender. Lift your right knee and go into a pirouette – if you can – and the game’s on.

Viewed from the side, a modern river kayak looks rather like a double blade, so there’s not much resistance when you pirouette over your ender. An ender, then a pirouette, then with luck a reaching reverse stroke and you can drop straight back in the hole. Another ender and pirouette, then a cartwheel, a barrel roll, another ender, a full spin, another cartwheel… A novice’s nightmare becomes a river-jock’s delight.

But me? I’m a backwater guy with dam training used to water staying where you can see it. By frantic flailing of my paddles I missed the hole and nibbled the edge. I heard the sucking and shied away but fell out anyway. Fortunately flowing water tends to spit unwelcome objects into eddies, which is where I became reunited with the kayak.

It got me interested in moving water though. Water’s strange stuff. In a glass or frozen or boiled it’s reasonably straightforward. But when it starts to flow the physics of water becomes unspeakably complicated. It’s for good reason that fluid dynamics is one of the most complex branches of physics.

It obsessed Leonardo da Vinci. When he wasn’t painting, planning a sculpture, constructing a war machine for Ludovico Sforza, dissecting corpses, designing a helicopter, grinding lenses or planning some great building, he could be found peering into rivers. He’d sprinkle grass seeds into flowing water to see what happened to them in whirlpools. Or, with superhuman quickness of eye, he’d sketch patterns in the near-infinite complexity of fluid vortices.

Image: Supplied

I have since run rapids in slower rivers and crossed bits of ocean in a sea kayak. I also did a memorable trip along the waterways of southern Madagascar and across the lake of elephant ears (they’re plants) while lemurs and chameleons peered speculatively at humans splashing around below them.

But I have retained my childhood love of the majesty and mystery of a meandering wetland, lake edge or slow, stately river drawing life towards it from the surrounding countryside.

Early paddlings on my gawky Anastasia predisposed me to enjoy the writings of the American writer Henry David Thoreau. He withdrew to Walden Pond in the mid-19th century because “I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived”.

Deep in the mangroves, Madagascar. Image: Don Pinnock

It slowed him down to walking speed, taught him how little of the bounty of the earth it took to sustain him and how the rhythms of the seasons were also the rhythms of his heart.

“Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in,” he concluded. “I drink at it; but while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is. Its thin current slides away, but eternity remains. I would drink deeper; fish in the sky, whose bottom is pebbly with stars.”

That’s backwaters for you… DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Beautifully written – makes me want to get out on the water again soon

Hello Don. I see from your article you are a Queenstonian. What years were you there? I used to live in the Bongolo basin.

Another great article from you. 👏

The problem with the cheese and tomato sarmies my mom made for me, I found, was that by lunch time the tomato had attained a stale malodour and the bread was soggy. BTW, have you ever read the story about when Graeme Addison gets caught in a hole on the Orange River? Great fun.