RUMI-NATIONS

On reading poetry and quarrelling with myself

If I had my way at the moment I would only write poetry and I would only read poetry.

Before I sink into the big sleep

I want to hear the scream of the butterfly

This is not a strategy to escape the harsh realities of a crisis of violence, criminality and inequality in our country or a universal free-fall of civility and civilisation. In fact, it is the opposite; it is my strategy to try to communicate better and better to hear, understand and connect with the things the world is trying to convey to us through our primary medium of communication: words.

No violence starts without words. There’s no problem there. Words are the most powerful weapons we have. But how do we use words to heal and to ignite and propel change? As a writer and an activist, I am fearful that bad reading habits — haste in particular — is neutralising the restorative power of words. We write so many words to audiences who don’t connect; to a news readership that often skim-reads, anxious for ‘news’ and ‘hard facts’ — but not for meaning.

In the midst of universal urgency brought on by the inequality crisis — upon which Covid settled like a bird of prey — I want more slowness, not just more speed; more acknowledgment of uncertainty and vulnerability than pre-cooked prescriptions.

For my 57th birthday, I was given a book called A Little History of Poetry by Oxford professor John Carey. Despite the craziness around us, I made time to read it from the first line to the last line. Many of the poems and poets it traverses are familiar to me, but nonetheless, it shifted my sensibility. I found it talking to all my worries about words. For example, amongst its many riches, I came across a poem by Robert Graves, called The Cool Web said by Carey to be a “poem about the impossibility of writing poetry”. Graves regrets “the cool web language winds us in”, lamenting:

But we have speech to chill the angry day,

And speech to dull the rose’s cruel scent,

We spell away the overhanging night,

We spell away the soldiers and the fright

Egged on by the power I feel in some of my fellow poets I’m also beginning to rebel against the artificial certainty of writing prose. There is something in its construction that feels intrinsically false: There must be full stops to every sentence — whilst there are no convenient full stops to experience. There must be logic, progression, a teleology that ontology would deny.

There must be rows of paragraphs, like terraced houses, always a beginning and always an end.

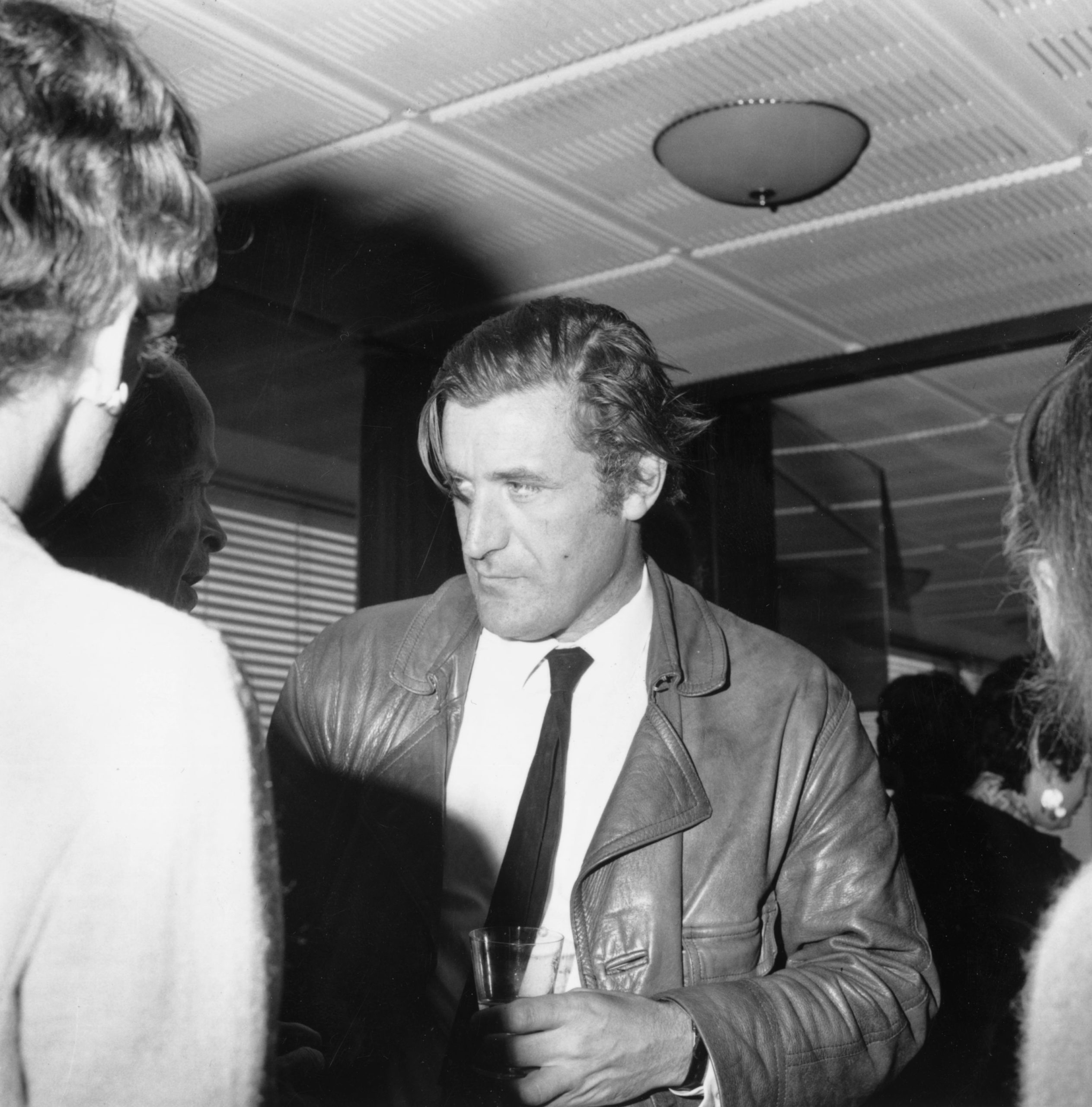

Not by accident perhaps, I came across Ted Hughes quoted as writing that “words are continually trying to displace our experiences. And in so far as they are stronger than the raw life of our experience, and full of themselves, and all the dictionaries they have digested, they do replace it.” I make a pencil mark beside his words. NB.

British poet Ted Hughes (1930 – 1998), later to become poet laureate, at a party. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

To this, I find I prefer the adulteries of art, malformed words, broken rhymes. I want to escape what DH Lawrence (in his poem Snake) calls “the voices of my accursed human education.” I can suddenly understand why Samuel Beckett shrinks the universe in Endgame and his broken play, Not I.

Playwright and writer Samuel Beckett (1906 – 1989) attending a first night performance. Original Publication: People Disc – HA0042 (Photo by Reg Lancaster/Getty Images)

At this moment of existential crisis we have to unlearn to understand; disconnect to (re)connect. Or as Paul Evans puts it in his 2020 collection, Poetry Rebellion, we have to “rewild” the spirit and our imagination.

***

These thoughts had been gathering for many months but have been solidified by two recent experiences.

Firstly, I have been reading poetry with my son, Aidan, ostensibly to help him prepare for matric. I’d like him to understand the swell that wordplay engenders, the rhythms that emerge; how images words create and their sounds combine; how the best images are often the broken ones; how we find meaning when we have to look for it rather than we are told it.

We read the set poems together, out loud and then reread them line by line, word by word. Even tired old, I found what came to life amazing.

In his prescribed readings I discovered such ostensible opposites as British poet Carol Ann Duffy, writing about love and language in her terse poems Syntax and Text; then on to Tatamkhulu Afrika, writing about disappointment (in Nothing’s Changed) and the dignity of the poor. I found my way back to Nigerian writer, Wole Soyinka’s ‘Telephone Conversation’, an ironic disquisition on ‘whiteness’ and racism, written in 1962, decades before it became ‘woke’ to wax unlyrical about ‘whiteness’. And yet the language and description was so last Tuesday and next Thursday. The racism Soyinka described could have belonged to many of the people I see and hear every day. He mocks it gently and authoritatively.

Wole Soyinka takes part in a debate at Liberatum Berlin hosted by Grey Goose vodka at Soho House Apartments Berlin. (Photo by Andreas Rentz/Getty Images for Grey Goose)

Reading poetry with my son and simultaneously journeying with Carey through his Little History reminded me of the sweep of poetry.

I forgave Carey for his Eurocentrism, he doesn’t know better, it’s for someone else to fill the gap, including with a little history of African and Eastern poetry.

I felt so glad that schools still teach poetry, but I wished it was more than a tick box in our accursed and out-of-kilter human education. Developing a lifelong relationship with poetry depends on how it is shared (not taught) and read with you as a child. For most children, it’s a passing blip. A strange and anachronistic bauble on your education: often made a test of memory, not meaning. Something needing speed to pass through and pass, not slowness.

***

My second experience was a few hours spent watching the majesty of sunrise in a corner of the Pilansberg. As the sun crept over the alkaline perimeter and into the volcanic bowl it encompasses, it brought to life shades and shadows, a thousand greens, a grazing herd of elephants. But it also brought trauma: That there could be such tranquility and splendor, yet over the hills, not even a crow’s fly away, the same land had been despoiled by platinum mines, degraded by poverty and the violence that trails in its wake. Blood and earth. Marikana.

Lines from Jim Morrison’s prescient poem, When the Music’s Over, floated into a space he would never have thought his words could have found:

What have we done to the earth?

What have we done to our fair sister?

Ravaged and plundered and ripped her and bit her

Stuck her with knives in the side of the dawn and

Tied her with fences and dragged her down

All this took me back to the sweep and “crazy clairvoyance” of the poetry contained in Carey and Evans’ anthologies. Both are encyclopaedias of emotion, portkeys to another way of feeling history, not as something detached from us but as variations on recurring themes of the human being; instincts and emotions that we can’t escape because they are wired into us — love, justice, celebration, loss, community; each playing over and over and over again. The variations emerge mainly because human agency and technology changes the physical world around us, the world we inhabit. But such is the speed of that change in recent decades that poetry itself is changing again.

When in Ode to the West Wind ‘red Shelly’ wrote

O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

He knew the answer to his own question.

But now — because we didn’t read or heed generations of poets — the world is weird, out of sync. Parts of the world skip spring and in others spring now consumes rather than regenerates. Nature is eating itself and us, rivers and seas carry poison rather than restoration; it causes grief, before communion, winter pinches, there are more “houseless heads and unfed sides”, justice is an abstract notion dreamed up by poets of an earlier age.

In this context poetry, as a history of human feeling, provides us with the means to separate thoughts and step back from the maelstrom of the moment, to see ourselves as one more species of animals in the game reserve of planet earth.

Yet when all is said and done it is those core human emotions and the natural beauty that surrounds us that may (note I do not say “will”) save us from ourselves.

Carey devotes a whole chapter to WB Yeats, himself an epitome of the vagaries of emotion and belief that infect the “foul rag and bone shop of the heart”. He quotes Yeats as writing that “we make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, out of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.”

Which brings me back to my quarrel with myself.

Prose or poetry?

At 57 I desire to bend the arc of the universe towards justice in the world as desperately as I did when I was 15; the only thing that has changed is the world around me and, contrary to my youthful hopes, it has become more divided and desperate. Carey quotes the poet Keith Douglas as saying: “I see no reason to be either musical or sonorous about things at present.” Neither do I. And yet, with our unflinching focus on what is bad, and on critique, we also need to retrieve what is good, not as escapism, or denial, but as a source of energy to intervene in a moment of peril.

Evans, in ‘Rewilding the Rebel’, the introduction to his anthologic celebration of poetry, asks:

“So, should the poem go extinct? If all it can do is scrawl slogans on monuments to the fallen species it survives, doesn’t it deserve to die with them? Can the poem dare something more than hope?”

The answer is that a poem can do anything it wants to do. The problem is not the poem, it is the medium. It takes two to stanza. The problem is not necessarily the writer, but the reader. You have to want to read poetry, shake off notions that it’s archaic or abstract or self-indulgent. That there isn’t time in a day. The problem is the ability of the reader to receive and recognise the signals, to slow down, to make yourself vulnerable to connection. It is about good writing, not the form of writing.

What is the role of poetry? Perhaps the notion that something must have “a role is” part of the problem.

Poetry is to be. DM/MC/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a beautiful piece of prose in praise of poetry. I am just amazed that Mark could confine himself to a short piece when he is so aware of the sky-reaching hopes and joys and the bottomless chasms of despair offered by poetry. Beautiful Mark. Maybe DM could offer a weekly poem in addition to a weekly recipe,

Marie, I would second that request. And perhaps Mark would write a Short History of non-European poetry for us?

Thank you for this thoughtful piece. I particularly liked your reminder that we need to disconnect to reconnect and your view that we need to retrieve what is good, not as escapism, or denial, but as a source of energy. When doing comes back, so will singing.

Mark, thx, well said. Tatamkulu Africa, has touched me deeply years ago, and I think it is time to go back there, amongst others. The deepest emotions are usually moved by such poets. Regards.

Such an amazing piece and a complete eye opener for me who has neglected poetry for most of my life. Thank you!

“At this moment of existential crisis we have to unlearn to understand; disconnect to (re)connect. Or as Paul Evans puts it in his 2020 collection, Poetry Rebellion, we have to “rewild” the spirit and our imagination.”

To me this says it all; too many broken issues to unlearn, to banish from our cluttered minds; we seem to be stuck in a morass of subjectivity where everyone else is wrong, but I. Thank you Mark, for opening our eyes, again, to the beauty of words

A glorious reminder of what we miss when we focus only on the material world; this resonates with the need to embrace spiritual values amidst the endless torrent of words seeking to explain and justify what cannot be forgiven. Thank you, Mark.

What an inspiring ode to poetry. I just begun reading poetry again since highschool. Poetry can be a powerful motive force for deep introspection.