OP-ED

Reflections of a Wayward Boy: Bearing witness to the birth of Equatorial Guinea

The typewriter I had access to was in one of the locked offices and the post office, the only direct contact with the outside world, was closed. I was the only foreign journalist on the island and I couldn’t report on this most anti-climactic birth of a nation.

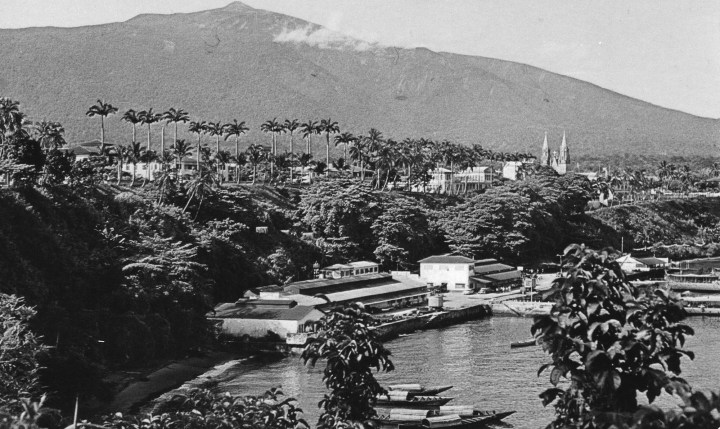

A subsidised third-class sea voyage in a Spanish colonial supply ship from Cadiz to the last sub-Saharan outpost of once imperial Spain provided an unexpected insight into the realities of race and class. It also gave us some idea of the history, geography and worrying potential of what was to become, in the most anti-climactic circumstances, the world’s newest independent state, Equatorial Guinea. We intended to stay there for just two days, but ended up stranded for more than two months.

The naval detachment in dress whites snapped to attention and presented arms as a gold-braided officer barked an order. Then, to a chorus of boos and jeers from hundreds of onlookers, the Spanish flag officially came down for the last time. That was Act 1 of Equatorial Guinea’s Independence Day, October 12, 1968.

Act 2 followed immediately: to loud cheers, clapping and some shouted jeers directed at the nervous-looking naval detachment, the Guinean flag was raised. And so the world’s newest independent state was born, with not even a whimper, let alone a bang. Barbara and I were the only pale faces in the crowd that milled about watching as the naval detachment shouldered their rifles and marched away toward the harbour and the grey warship anchored in the bay.

The symbolism of the event seemed to dawn on the crowd: to jeers, they had seen off the representatives of imperial Spain. With much chatter, smiles and laughter, groups began to make their way down the hill from what had been the governor’s mansion to the deserted town centre where every window and shopfront was shuttered.

The typewriter I had access to was in one of the locked offices and the post office, the only direct contact with the outside world, was closed. I was the only foreign journalist on the island and I couldn’t report on this most anti-climactic birth of a nation. So Barbara and I were swept along with the crowd into the back streets of Santa Isabel (now Malabo) to toast Independencia in the small bars crowded with jubilant Guineans. Many, with throat-cutting gestures, promised dire consequences for any remaining Spaniards, aware that half of the once 6,000-strong Spanish population had already fled.

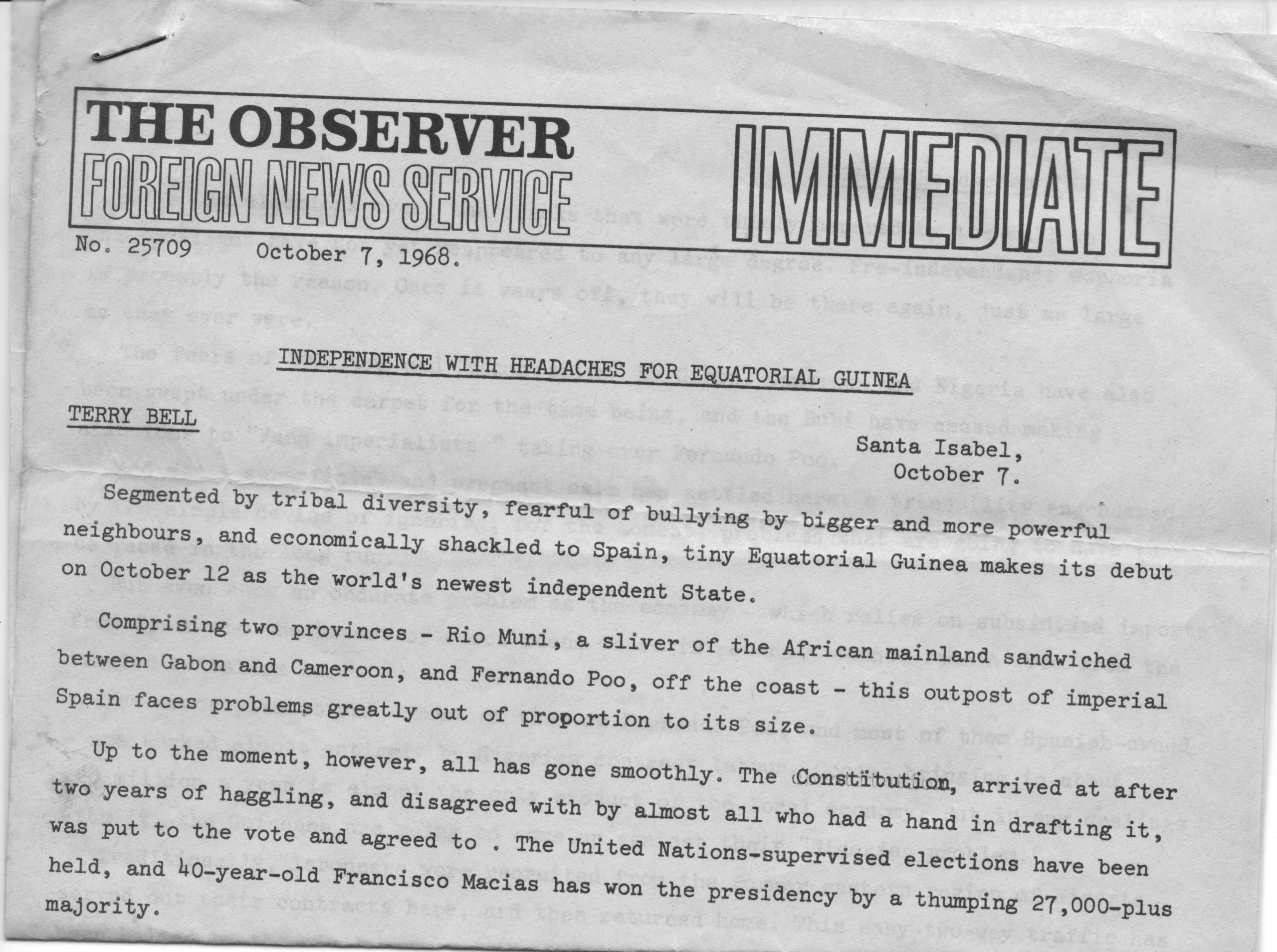

The opening lines of Terry Bell’s preview feature filed for the Observer Foreign News Service on the imminent independence of Equatorial Guinea. (Courtesy Terry Bell)

At least I had been able to send a typed pre-independence feature, carried by an oil company engineer flying to London, to be published by the Observer Foreign News Service. But this independence day was a highlight after being stranded for nearly three months on Fernando Poo (now Bioko) and just three days before we intended winging our way, via Douala and Kinshasa, to Ndola in Zambia, putting behind us all the trials and tribulations of the recent past. It would be a decidedly upmarket departure having arrived as third-class passengers aboard a Spanish supply ship that had taken a couple of weeks to ferry us from Cadiz via the Canary Islands and Liberia to Equatorial Guinea.

Third-class accommodation was cheap, but hardly cheerful: two-tier steel bunks very much below decks in the stern of the ship. Dimly lit, hot and stuffy, the male dormitory on the port side, female, opposite. Metal stairs led to a room with benches, stools and tables and a window overlooking the hold with the crane/mast at its centre, across which lay the two decks of first and second-class cabins and the bridge. Meals comprised some of the leftovers from the first and second classes. But it was here that we also received a first-hand lesson in matters of race and class, along with some knowledge of the people, the history and the geography of our destination as well as considerable help with my very poor Spanish.

When we boarded, along with a contingent of young Spanish naval conscripts from rural peasant and working-class families, we had only a vague idea about Equatorial Guinea, the last sub-Saharan outpost of once imperial Spain. We were not even sure whether we should disembark in Rio Muni, the sliver of the African mainland sandwiched between Gabon and Cameroon, or at the first port of call, the main island of Fernando Poo. Either way, we did not intend to spend more than a day or two in Equatorial Guinea before heading across the continent to Kenya.

The ship had sailed to Cadiz from the northern Spanish port of Bilbao with two Guinean third-class passengers who barely nodded in our direction when we boarded. They also never uttered a word to us or to any of the sailors, merely nodding curtly when they were greeted. They sat at a table in a corner of the room, talking quietly to one another and playing with poker dice. When, on the second night, we invited them to join us at what was obviously an alfresco film show, they merely nodded rejection. But a screen had been erected on the mast and rows of chairs set out on the deck above the first and second class cabins, facing it.

There were clearly enough seats, given the few passengers aboard, so Barbara and I led the group of sailors across the hold and up to the chairs. But we had no sooner sat down than a thin, sharp-faced man in a suit appeared and ordered us out. If we wished to watch the movie, we should sit below, on the hold. A clearly nervous first officer, in English and speaking on behalf of the captain, whispered that the man in the suit was “Guardia” (police) before virtually pleading with us to go.

As the sailors scrambled back to the third-class quarters, we left, but not before Barbara, glaring at the then smirking policeman, let fly with a string of expletives that ended, I recall, with him being dubbed a “fascist shit”. It was an outburst that was later to cause us some concern.

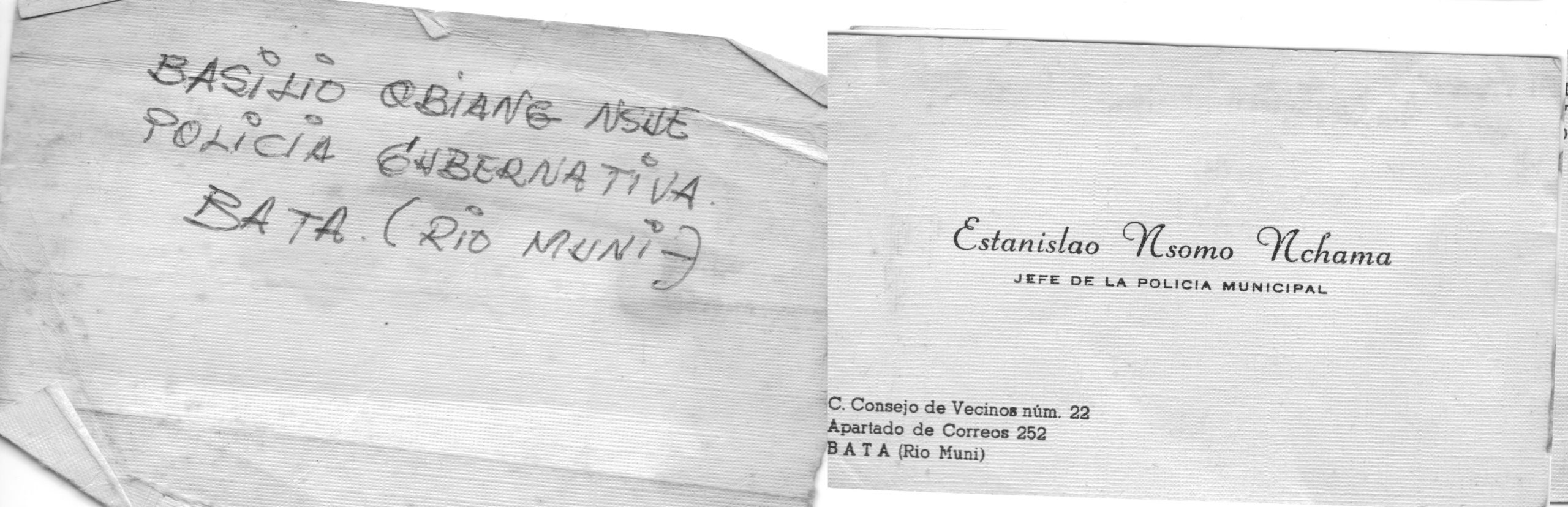

At the time, we were simply furious and tried to get the sailors to agree not to demean themselves by accepting such treatment; to boycott the movies. That was when Estanislao and Basilio introduced themselves and, hearing we were from South Africa, welcomed us as “fellow Africans” who were wasting our time trying to persuade Spanish conscripts not to be treated like dirt.

The business cards of Estanislao Nsomo Nchama (printed) and the handwritten one of Basilio Obiang Nsue, whom Terry Bell encountered during his third-class passage to Equatorial Guinea on a Spanish supply ship. (Courtesy Terry Bell)

Estanislao Nsomo Nchama was the chief of the municipal police in the mainland capital of Bata; Basilio Obiang Nsue was an officer in the national police. Both had been in Spain on specialist courses prior to independence; both probably outranked the officer who had lorded it in the first and second-class areas. “But,” said Estanislao patiently, “things will change.”

At least we had some idea of what to expect when we landed on an island that was then the base for an international aid airlift to civilians caught in the secessionist war raging in Nigeria/Biafra. Our new-found friends also advised us that it was best to disembark on the island, take a subsidised flight to Cameroon and make our way from there. We took their advice and decided to move as quickly as possible to get across to the east coast and then on down to Dar es Salaam. But a series of circumstances soon scuppered those plans and led to some fraught situations — and that memorably peculiar independence day. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.