MATTERS OF OBSESSION

La Mort du Prophète: Are the black holes more corrosive than the images they hide?

Raoul Peck reanimates archival footage in a meditative investigation of the fleeting and tumultuous rule of Patrice Lumumba, late prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo, whose fall from power and subsequent assassination were shrouded in censorship and mystery.

“A prophet foretells the future. But the future has died with the prophet. Whatever is said. His message has vanished, but his name remains. Should the prophet be brought back to life again? Or should the final traces of his memory disappear with the snow?” The lilting prose of Peck’s voice asks us, layered over slow footage of heavily clad bodies trudging through the icy streets of Brussels.

The prophet in question and the subject of Peck’s La Mort du Prophète is one Patrice Lumumba, an uncompromising and revolutionary figure who played a central role in the fight for the independence of the DRC in the early 1960s. Lumumba’s story is tragic, fleeting and complex. Assassinated under mysterious conditions, the power struggles that led to his demise were murky with the fingerprints of Western intervention.

Patrice Lumumba (1925 – 1961), Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo, is met by British statesman John Profumo (to left of centre) upon his arrival at London Airport, en route to the United Nations in New York, 23rd July 1960. (Photo by Douglas Miller/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In the preface to his book The Assassination of Lumumba, Ludo de Witte, a famous Belgian sociologist and historian, claimed that Lumumba’s death was “one of the 20th century’s most important political assassinations”. Lumumba’s story is impossibly convoluted, a truth that Peck’s experimental style and a-linear plotline embody.

Here follow the bare-bone facts.

Lumumba was elected prime minister under President Joseph Kasavubu in June 1960, the day the DRC officially shook off Belgian rule.

A visionary, Lumumba’s goal was the total independence (political, social and economic) of Congo from colonial powers. A goal that, for obvious reasons, did not sit well with the Belgians, who were under the impression that they would get what Jean Kestergat, an international correspondent from Belgian (interviewed for the documentary in 1981) calls the “Belgian Bet: a Congolese government, a Congolese parliament, with an administration which would contain a large Belgian presence.”

Almost immediately after Independence Day, Moïse Tshombe, a politician from the province of Katanga, took advantage of unrest in the army to carry out a secession. The province is the richest in the nation; the newly instated DRC could not afford to lose it. The secession also gave the Belgians an excuse to send troops back into the country under the guise of protecting Belgians from harm. The troops they sent, however, landed almost exclusively in Katanga and blatantly fought to oust Lumumba.

Lumumba, in an attempt to halt the conflict, appealed to the UN, which was wholly unhelpful and, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “condescending and assertive”. This effort having failed, Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union for help.

At this point the Western powers (spearheaded by the US) got involved. It was 1960, the Cold War was raging and the Red Scare was in full swing. Further, Peck’s voiceover tells us, the raw materials used by the US to make the atomic weapons detonated in Japan at the end of World War 2 came from mines in Katanga; it’s clear that while the official reason for US concern was “saving Africa from communism”, the world superpower had a vested interest in retaining some hold over Congo.

The Western powers encouraged Kasavubu to dismiss Lumumba as his prime minister, which he did. At the same time the CIA was providing funds and weapons for the Congolese army, now headed by Colonel Mobutu. With the backing of an army fuelled by US money, Mobutu took control of the DRC and Lumumba was put under house arrest.

The story comes to its tragic end when, in January 1961, after a turn of events that led the UN to officially recognise the new DRC government headed by Mobutu and Kasavubu, and the separate rule in Katanga of Tshombe, Lumumba and a few of his associates were flown as prisoners (with no objection from the UN, despite their knowledge that this would surely be a death trap) to Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi), the capital of Katanga and the hearth of Lumumba’s most bloodthirsty political enemies: Tshombe and the Belgian soldiers.

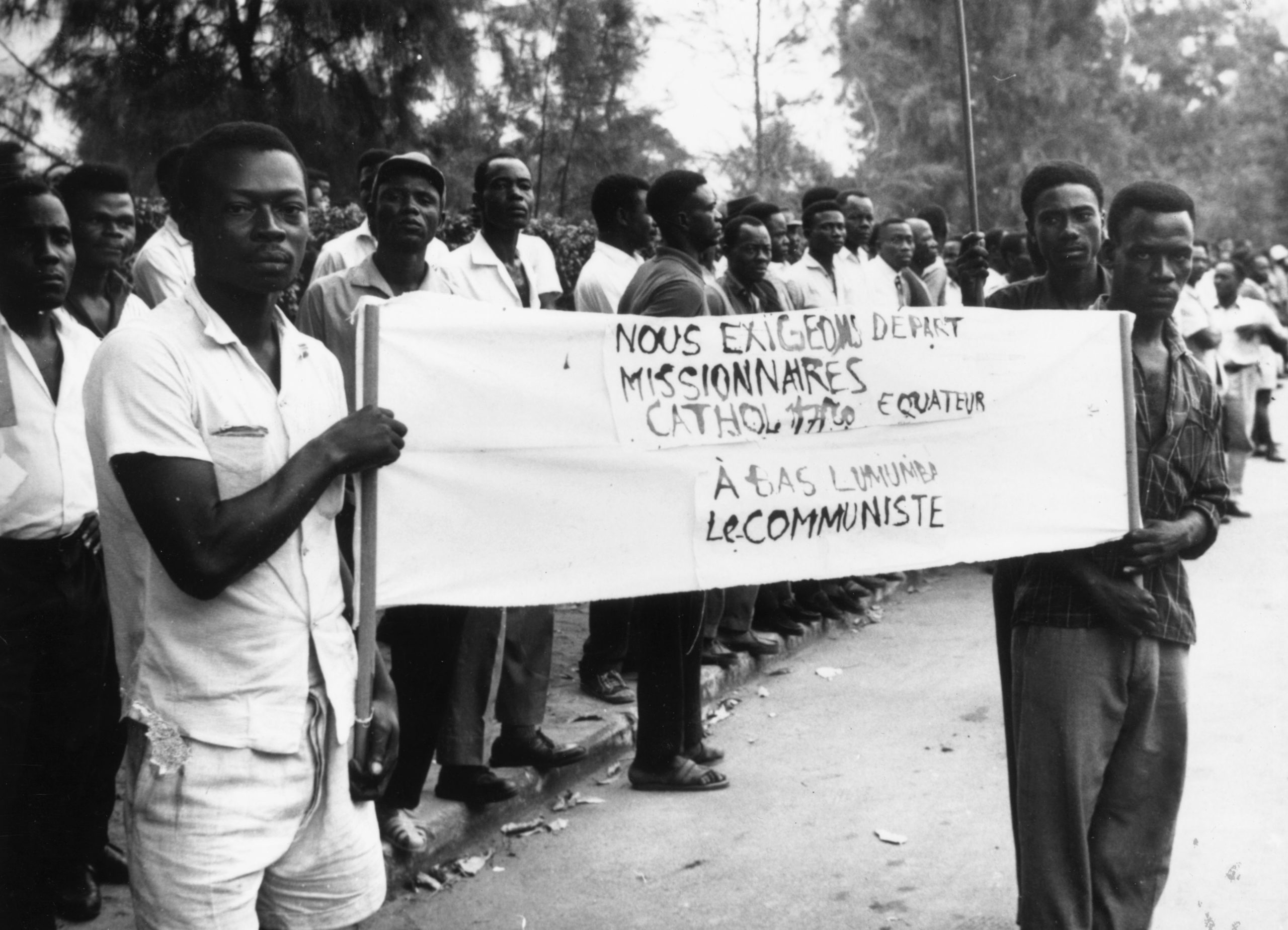

Demonstrators in the Belgian Congo protest against Congolese National Movement leader Patrice Lumumba, the day before the country gained its independence as the Republic of the Congo, and later, Zaire. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Unsurprisingly, Lumumba and his associates were executed (after being tortured/interrogated/starved/beaten for days) by a Belgian firing squad.

It’s the disturbing knowledge of what happened after the execution that gives Peck’s documentary the true source of its power.

A few days after the executions, after the bodies of Lumumba and his partners had been buried in shallow graves, the firing squad returned, under the direction of Belgian officers, to dig up, hack to pieces and dissolve the corpses in acid. The official announcement of the death came only a month later, and the Katangan government claimed that Lumumba was killed by unnamed villagers after escaping from their custody.

Like Lumumba’s body, much of the evidence behind this story was destroyed, the remaining facts twisted and mangled by Western journalists into something resembling a dark fiction. “Few events in recent history have been the target of such a ferocious campaign of disinformation as the war waged by the Belgian establishment against the first Congolese government of Patrice Lumumba,” writes De Witte. “In an attempt to prevent another Lumumba ever appearing again, his ideas and his struggle against colonial and neocolonial domination had to be purged from the collective memory.” But this purge left gaps and tears in the fabric of history, what Peck refers to as “black holes”.

“Should the prophet be brought back to life again?” Peck asks his audience.

The ghost of Lumumba dances through the documentary. Peck reminds us that the prophet’s murderers were unable to show his body. He says, over footage of a man and a woman waiting at a train station in Brussels, “he [Lumumba] roamed this city, returning to tickle the feet of the guilty”.

17th February 1961: A group of women in Accra, Ghana, during a mourning parade for Patrice Lumumba, the murdered former Premier of the Congo. The slogans read ‘Mobutu and Tschombe must be hanged,’ ‘Kasavubu the traitor’ and Hammarskjold must be sacked’. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Peck resurrects the prophet. He carves pieces of the truth out of old pictures of Lumumba, sound bites, interviews, small video clips, video footage from his [Peck’s] own childhood home in Kinshasa and visuals of Belgian citizens walking around in Brussels. He builds a full and comprehensive story about the rise and fall of Lumumba out of anything he can find. That is to say almost nothing. That is to say the smallest traces left behind after attempts at erasure.

“Are these black holes more corrosive than the images they hide?”

More than anything, La Mort du Prophète is a story about silences.

A haunting part of the film comes near the beginning, in a depiction of Lumumba’s speech on Independence Day. He gave what Peck’s voice-over refers to as “an unconventional speech […] He is about to say things best left unsaid.”

The beginning of the speech, documented in black and white – a moving picture with sound – is fairly conventional: Happy Independence Day, Lumumba is saying.

Then the screen goes black, and Peck’s voice-over returns: “The images have been lost… the voice still remains.” We watch a blank screen as Lumumba continues on to the controversial part of his speech, the brutal truths that the Belgian Kingdom has been trying to sweep under the rug for centuries. “We have known ironies, insults. We have had to submit to beatings, morning, noon and night, because we were negroes,” says Lumumba’s formless voice. The blank screen is a clear indication of attempted destruction of the evidence of this pivotal moment. This is a truth half-destroyed. In leaving the screen blank, Peck does not try to fill the hole that was created in this destruction. Instead, he makes viewers aware of it: there is no denying that something really awful is being covered up. History is a winner’s game, Peck is reminding us. Those who are in power can control what those who are not are able to see.

“Are these black holes more corrosive than the images they hide?” If you are innocent, then why keep secrets?

Lumumba’s story is not alone in its nefarious censorship, but it’s particularly important. As Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja wrote in The Guardian: “In Congo, Lumumba’s assassination is rightly viewed as the country’s original sin […] It was a stumbling block to the ideals of national unity, economic independence and pan-African solidarity that Lumumba had championed, as well as a shattering blow to the hopes of the Congolese for freedom and material prosperity.”

The nation has been wracked by conflict on and off ever since. Peck’s La Mort du Prophète reminds us that history lives on in the present, and the parts of it that are purposefully erased and silenced, like black holes, are particularly corrosive. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.