TRIBUTE

Mzilikazi James Khumalo leaves the podium for the final time

The passing of South African composer and educator Mzilikazi Khumalo requires that we understand the importance of what he achieved and how many mountains he had to climb to do so.

Linguist, educator, composer and humanist Mzilikazi James Khumalo passed away on 22 June 2021, bringing to a finale a rich intellectual and cultural career that connected strongly with the nation’s artistic heritage and then touched audiences around the world. (His wife Rose, a constant companion for half a century, also slipped away just a few days later.)

Beyond his academic work, his considerable energies focused on preserving the musical heritage of the nation and then in bringing that heritage – most especially the Zulu musical legacy – to the attention of the rest of the world. The well-deserved international reputation of his two major works, the oratorio or musical epic, uShaka kaSenzangakhona, and the opera, Princess Magogo, have sometimes overshadowed his many other activities; but, taken together, his collective efforts have been an important element in nurturing an emerging South African national cultural identity.

Mzilikazi Khumalo was born on 20 June 1932 into a deeply religious family of pastors, then living on a KwaZulu-Natal farm owned by the Salvation Army, as the eldest in a family of seven children. In that family, each child learnt to play musical instruments and, over the years, he studied music through the Royal School graded lessons and examinations as well.

In her published tribute in City Press this past weekend, his sister, journalist Nomavenda Mathiane, wrote of her brother: “My life with him began in the early 1950s, when we were living in Western Native Township, where our parents sojourned while in charge of the Salvation Army church. Cramped in this tiny, two-bedroomed township house, life seemed to be a perpetual struggle. We watched our parents battle to make ends meet on a meagre church salary. However, in hindsight, those were the best times of our lives as a family. We enjoyed many evenings of song, laughter and breaking bread.

“At that time, Mzilikazi had completed training as a teacher at the Pretoria Normal College, where he studied with Desmond Tutu, [and writers] Doc Bikitsha, Stan Motjuwadi and Casey Motsisi, to mention but a few. Bhuti was an all-rounder. He was not only an academic, but a sportsperson who played tennis and cricket – and boy, did he look great in his white cricket outfit!

“He then taught at Wallmansthal Secondary School while studying for a BA at Unisa. In the tiny Western Native Township, Mzilikazi was one of the few to acquire a degree.”

In conversation, Mathiane added that as the family expanded and as he grew up, Mzilikazi Khumalo naturally came to exercise a kind of parental responsibility over his younger siblings. In his adult years, he regularly paid close attention to the welfare of all the members of his extended family. Mathiane said her sibling always showed great familial pride in each person’s accomplishments, regardless of whether they were scholarly achievements or their work as a carpenter.

Given the realities of apartheid South Africa, an intellectually curious Khumalo directed his ambitions towards becoming a teacher. Then, after teaching in a township high school, he eventually moved on to the University of the Witwatersrand where he became a language instructor (and eventually professor) in isiZulu as well as other African languages. His postgraduate research and writing concerned tonology, an aspect of the discipline of linguistics that focuses on the interplay between intonation and meaning in spoken language – a topic that may have had some special relevance in exploring a fuller understanding of the texture of communication in the various African languages he knew, and in many cases, the distinctive clicks that formed elements in the aural landscape.

Then, in the early 1970s, he became a special Fulbright lecturer in the US at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Illinois, for their African languages programme, and I first met him shortly after his return to Johannesburg. A few months later, one of the tasks for our embassy office was to interview and recommend applicants for the national slate of Fulbright scholarship awards for postgraduate degree studies in America. A key step for would-be candidates was a screening interview conducted by a panel of South African former Fulbrighters.

Given 1970s South Africa, the country’s racial realities would almost inevitably have meant such panels would only consist of white academics. But having now met Khumalo, and having learned of his US university teaching experiences, it seemed entirely appropriate to ask him to serve on our screening panel. But that encounter with him actually gave me no hint of Mzilikazi Khumalo’s life in music, let alone how just important that role would be for the nation.

In a nation that seemed headed towards open conflict, for many participating choristers, black and white, it was the first time they had joined together in a musical activity with people of different races.

By the time Mzilikazi Khumalo had become a university lecturer, he had already had a long engagement with choral music, including his first compositions and leading his own choir. But his musical efforts became increasingly important for the country because of his central role in the “Nation Building” Choral Festivals. A brainchild of the late Aggrey Klaaste, the editor of The Sowetan in 1989, the festivals became a musical contribution towards healing rifts in a troubled nation in the final years of apartheid, at a time when it seemed entirely possible a real civil war might well erupt.

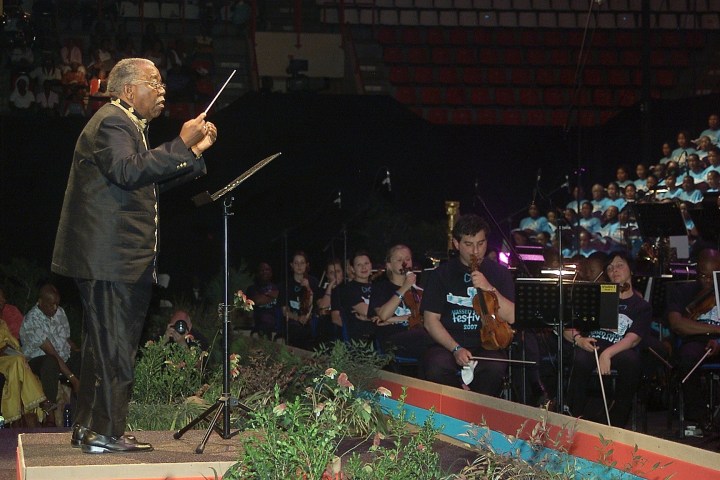

Dr. Mzilikazi Khumalo on March 30, 1988 in South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

Klaaste had brought Khumalo together with classical and choral conductor Richard Cock and another conductor, Danny Pooe, to create the festivals. Describing those efforts, Cock explained how seriously Khumalo had taken on this responsibility – the two men travelled around the countryside, despite the difficult conditions of that time, to audition potential choirs for the festival. Thereafter, Khumalo would visit each of the choirs chosen for the festival, before they all came together in Johannesburg for the performances, to ensure every choir was correctly preparing the music he had selected which all the choirs would sing in unison with their hundreds of voices.

In a nation that seemed headed towards open conflict, for many participating choristers, black and white, it was the first time they had joined together in a musical activity with people of different races. Those divisions Khumalo and his colleagues had sought to erase through music was also a response to the way earlier nonracial and multiracial cultural activities in the country that had been forced to wither under apartheid.

Along the way, Khumalo also came to have an increasingly influential role in the South African Music Rights Organisation (Samro). One such project, again in association with Cock, was a series of carefully edited compilations of traditional and composed melodies, along with full piano accompaniments. They were printed with the notes for the singers in both Western-style staff notation and, significantly, tonic solfa notation. The latter is the syllabically based notation – do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do and other related syllables for sharps and flats – African choirs and singers have traditionally used as the notation they sang from, rather than that lesser-known staff notation. For Prof Khumalo (and by now, everyone called him that), it was crucial to have both forms on the pages together to ensure the nation’s music would be accessible to everyone who wished to perform it, regardless or whether they had been exposed to staff notation.

Andre le Roux, who had worked closely with Mzilikazi Khumalo while Le Roux was a senior officer at the Samro Foundation, said of the older man’s presence there: “When I started at Samro in 2006 he was there and firmly entrenched as Samro vice-chairman, Samro Endowment for the National Arts vice-chairman, composer in residence of sorts and authority on all things choral, musical, African and indigenous. He was the wise man of music that many came to see and drink from his cup of wisdom. The difficult discussions we had were numerous but entertaining and I often felt like a student in his presence being gently mentored and at times castigated.” But never ignored.

Then, following the establishment of the nation’s nonracial democracy, Khumalo also became an active participant in the special commission that created the country’s new national anthem, drawing the nation’s anthem of struggle and hope, Nkosi Sikelel’ Africa, with Die Stem, the official theme music of the apartheid regime. The new, combined anthem had multilingual lyrics and a musical bridge to bring the two songs together into one combined anthem. While the new anthem remains controversial for some, for most South Africans it has become a tangible musical symbol of national reconciliation.

Of course, all along the way, Khumalo had also been working on his own composing. His first composition was Ma Ngificwa Ukufa in 1959 followed by other works for voice and choir such as Five African Songs that included a setting of the traditional melody, Bawo Thixo Somandla, further arranged for orchestra by Peter Louis van Dijk.

Then there was the song cycle composed on the legacy of songs by Zulu Princess Magogo, the daughter of King Dinizulu (Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s mother). Magogo’s father had tasked her with devoting her life to preserving the Zulu musical heritage at a time in the early 20th century when the Zulu nation had reached its lowest ebb.

A key element of Khumalo’s work [is the way] in which he has been trying to craft a South African nationalist musical repertoire out of indigenous materials as well as Western musical techniques in much the same way Romantic-era composers throughout Europe (and then in the 20th century in America) attempted to achieve.

Over the years, for Khumalo’s musical oeuvre, the accompaniments or orchestrations for his works – either in voice and piano settings or set for full orchestra, chorus and solo voices – had been arranged by Western-trained composers and orchestrators such as Van Dijk and Peter Klatzow. (As a footnote, credit between composer, orchestrator and arranger can sometimes be a vexed issue, but consider Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. The composer had originally written it for piano and after his death, others arranged it for full orchestra, with one arrangement, Maurice Ravel’s version, the one the world usually hears. But no one argues Ravel’s arrangement detracts from Mussorgsky’s own vision.) We should see Khumalo’s compositions as beautiful works further enhanced by the talents of skilled orchestrators to achieve their fullest realisation.

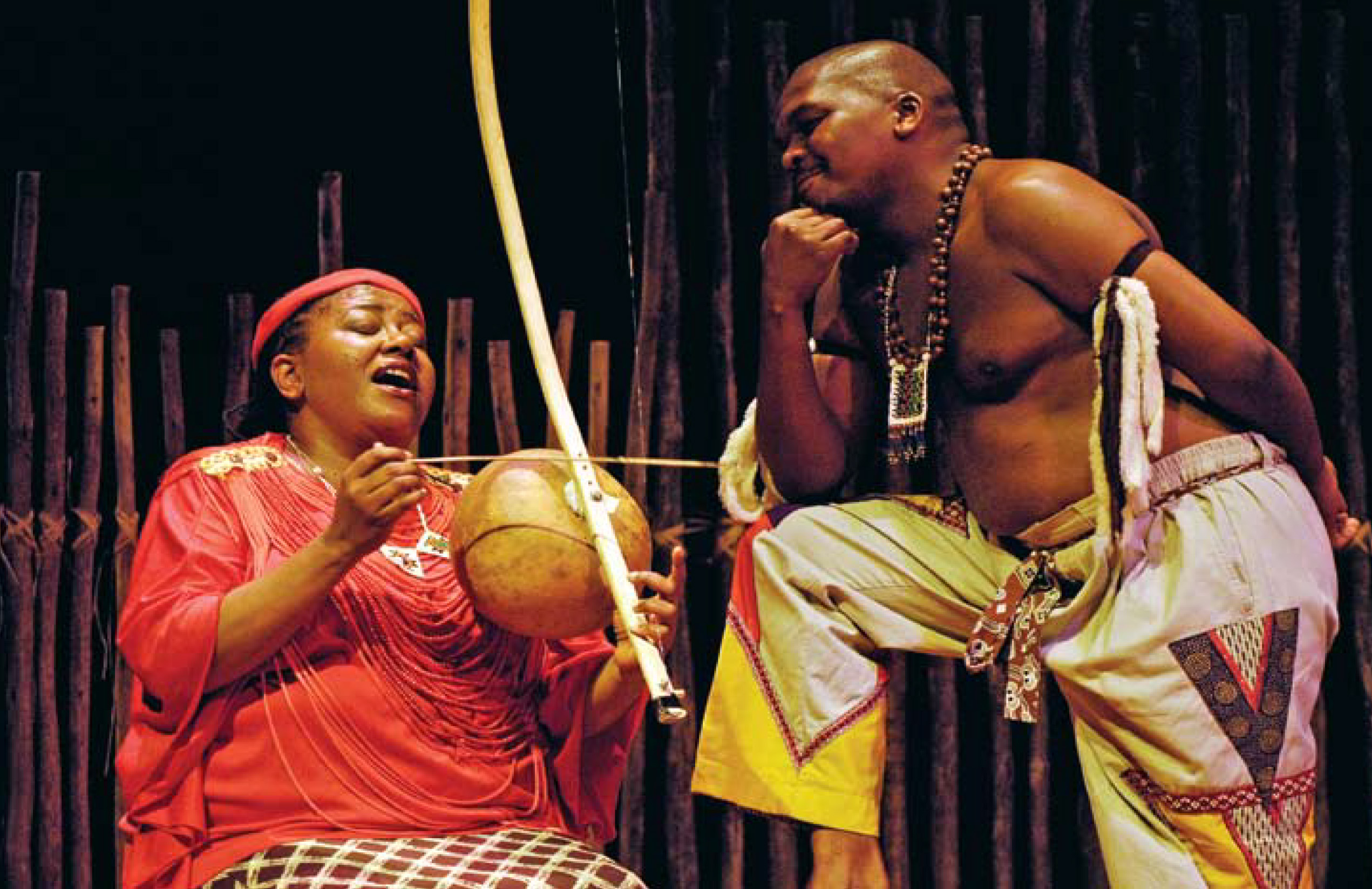

Sibongile Khumalo as Princess Magogo and Ntsikelelo Mali as Ndwandwe at Het Muziektheater, Amsterdam, in 2006. Image: Opera Africa

As a composer who had taken great pride in his Zulu heritage, Mzilikazi Khumalo was now sketching out a much larger work than anything he had previously tackled. This became uShaka kaSenzangakhona, a secular oratorio, or perhaps just a unique musical epic work. This work would tell the rise of a powerful king, Shaka, the man who had forged the Zulu nation, up until he met his death at the hands of an assassin. This work, uShaka, was composed to the extended poetic saga written by renowned Zulu poet Themba Msimang. Eventually, after Khumalo had set out the vocal lines for soloists and chorus, the question of the best orchestral underpinnings became important to the full realisation of the work.

In a review of a performance of uShaka several years ago, I had written that this work was strikingly reminiscent of the musical nationalism of 19th-century Europe, when I noted that “a key element of Khumalo’s work [is the way] in which he has been trying to craft a South African nationalist musical repertoire out of indigenous materials as well as Western musical techniques in much the same way Romantic-era composers throughout Europe (and then in the 20th century in America) attempted to achieve. Such composers used the folk tunes and melodic textures of Scandinavia, Central Europe, and then further East, as nationalism became an increasingly potent political force translated into artistic and cultural modes of expression.”

Princess Magogo tells the story of the Zulu princess from both a historical and personal perspective by combining the musical traditions of Europe and Africa. Image: Opera Africa

Initially, composer Chris James had been tasked with that challenge, but as there were concerns about his orchestral contribution, including a sense by the composer that the orchestral and choral parts were insufficiently integrated, as well as a feeling that the harmonisation of the orchestral accompaniment of the singing had not achieved what Khumalo had intended for his composition in his own mind.

At that point, American (but locally based) conductor Robert Maxym was called upon to work on an orchestral score that would respond to those challenges. As Maxym explained it, to get a better understanding of what Mzilikazi Khumalo had had in mind for the orchestral textures Maxym would now create, the two men sat together to listen to hours of recordings exploring two and a half centuries of choral/orchestral textures – from Johann Sebastian Bach on through to Gustav Mahler and Alexander Zemlinsky. They did this to ascertain precisely what Khumalo really wanted his work to be like as a fully realised, fully orchestrated work, with all the right orchestral bells and whistles. When the two finally listened to the two last composers on their list, Khumalo told Maxym that, there, in between Mahler and Zemlinsky, that was the texture and style he wanted to achieve for uShaka.

The opening music of a performance of uShaka

It then fell to Maxym to work out those textures in deference to that instruction. Eventually, with a fully completed score in hand for the orchestral musicians and a tonic solfa/staff notation score for the voices, rehearsals could begin in earnest, even though the composer, as he listened to rehearsals, sometimes made yet further changes, when he was not yet completely satisfied with the resulting sounds.

This is probably not how classical musicians usually rehearse a massive composition, but it all came together for enthusiastically received, live performances – with energised audiences sometimes jumping right in to ululate and whistle at the logical places. Eventually, too, funds were found to record the entire work for commercial release. (Listen to samples of that recording here.)

The stirring finale of uShaka

But Khumalo was not yet finished with composing massive musical works honouring his heritage – and creating wonderful music. For this second work, it would be an opera based on the life story of Princess Magogo, her own compositions and the difficult challenges of her times.

Poet laureate Msizi Kunene had first proposed the idea of such a work to Mangosuthu Buthelezi and the Zulu royal family, recommending that the new, Durban-based opera company, Opera Africa – headed by Sandra and Hein de Villiers and Professor Khabi Mngoma as chairperson of the opera company – be the organisation to take on this challenge. Poet Themba Msimang would again be called to write the libretto, and Mzilikazi Khumalo was the inevitable choice for composing this work. Durban-based playwright Themi Venturas would direct the work once it had been composed. With all this support, the project began.

Mezzo-soprano Sibongile Khumalo (the daughter of Khabi Mngoma but no relation to the composer) was the only choice as the lead, coming off her already considerable triumphs with Opera Africa and as a Standard Bank Young Artist awardee. Sibongile Khumalo had already appeared in those previous opera productions by the Opera Africa company and in performances of uShaka, and even more importantly, as a child, she had met the royal daughter and heard the music composed by Princess Magogo directly from her. Conductor Michael Hankinson was then brought to provide the orchestration required for a full-fledged opera, once Khumalo had composed the vocal music.

Describing the importance of this work, once it was completed and being performed, the eminent South African musicologist Christopher Ballantine had written in a review of it for Opera magazine: “If, as so many in South Africa hope, the 21st is to be the ‘African century’, this opera is likely to be looked back upon as an important early herald.”

Magogo’s initial performances around South Africa were very successful with audiences, and its uniqueness as a musical work had attracted growing foreign interest as well. In 2004, the project was picked as a centrepiece for the 100th anniversary season of the Ravinia Festival in Chicago, US. Ravinia is one of America’s most popular summer music venues. Reflecting on that choice, the man who was then the festival CEO, Welz Kauffman, wrote to us to say: “I was fortunate to bring Magogo and uShaka to Ravinia in 2004 and 2006 respectively, both of which were American premieres… Never before nor since have I had the pleasure of such transformative experiences with works of art. And to be able to actually present Opera Africa and their amazing artists and to spend time with Mzilikazi and Sibongile (and Sandra and her husband) – suffice it to say, unforgettable.

“And these experiences – both the staged performances and, importantly, the new relationships built with the Chicagoland community – continue to pay rich dividends today. Ravinia is thought of in a completely new light of diversity, inclusion and access, and the work we were able to do internally following the Opera Africa residencies have remade this institution, the oldest summer music festival in the United States.

“There are so very many examples I could provide you – packed houses of kids from disadvantaged parts of Chicagoland having their first Zulu experience at the historic Auditorium Theater in downtown Chicago; the dancers and drummers performing for the public out of doors on Daley Plaza, the very centre of Chicago commerce and government; visits by the Company to the major African American houses of worship including the fabulously musical United Church of Christ; my colleague Christine and I being taught some of the dances (Christine great, me not so much, but wonderful!); the first rehearsal of Magogo with the remarkable Chicago Sinfonietta in the pit – the Sinfonietta being the only orchestra in America specifically designed to engage musicians of colour – again, astonishing…

“And all of this prior to the performances themselves. And with the Magogo company with us, I asked Sibongile if she would do a concert in our intimate 850-seat theatre with jazz legend Ramsey Lewis on the piano – an unforgettable concert… ”

The city’s leading newspaper, The Chicago Tribune, added that Kauffman “saw Princess Magogo as an opportunity to open Ravinia’s gates to an even more ethnically and culturally diverse public. ‘It’s a piece that’s emblematic of everything we’re trying to do at Ravinia these days in terms of community outreach and education, even as it reminds people of Ravinia’s heritage as an opera presenter,’ Kauffman says.” Partly based on the extraordinary success of the opera in Chicago, two years later, the Ravinia Festival brought a full cast of uShaka for its audiences to enjoy as well.

In recent years, Mzilikazi Khumalo had been in poor health and had not composed additional works before his passing. Still, as Bongani Ndodane-Breen, one of the country’s leading next-generation composers (with operatic works on the lives of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Chris Hani, and an oratorio on the Freedom Charter already to his credit, among other works) wrote to me when he had learnt of Mzilikazi Khumalo’s passing, to offer his own judgement of the larger impact of the older man’s achievement.

As he said: “Although Khumalo’s output features celebrated vocal music, other composers collaborated with him in the realisations of his opera and oratorios as instrumental music was not part of his development as a composer. Apartheid South Africa had very restrictive access to quality higher education for black musicians where skills such as orchestration were developed. This did not deter Khumalo from establishing himself as a visionary choral composer capable of conceiving music for large-scale forms such as opera and oratorio…

“It is significant to point out the bridge Khumalo created in South Africa between choral music composition and opera as we are now seeing a new generation of black South African composers (recently Sibusiso Njeza’s Amagokra at Cape Town Opera) who were inspired by Khumalo’s Princess Magogo. Khumalo’s approach to oratorio and opera was catalytic in a nation with such talented singers, rich in untold history and unexplored mythology.”

An epitaph like this helps sum up the impact of Prof Mzilikazi Khumalo and his music on South Africa and the world – and how it will reverberate for years into the future. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.