OUR BURNING PLANET

CITES has failed the natural world. Here’s how it can be fixed.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, based in Geneva, was set up to protect endangered species, but it has as many holes as Swiss cheese and in places is plain rotten. Can it be saved?

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) was set up in 1975 to protect wild species from overexploitation, with 183 signatories agreeing to abide by its conventions. Now, nearly half a century later, it’s no longer fit for purpose and its regulatory model is no longer valid.

Legal trade, often in luxury goods, is decimating species. So is the parallel illicit trade, which is estimated at between $100-billion and $250-billion a year and which CITES has failed to prevent.

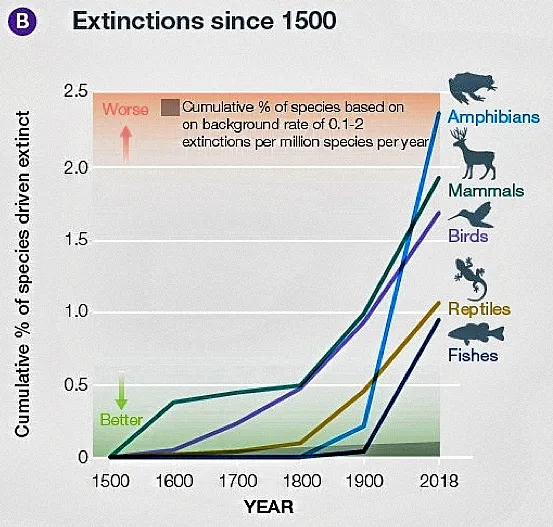

According to the Global Assessment Report by the International Panel on Biodiversity, nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history with trade being a key driver. As biodiversity crashes across the planet, many species are facing extinction — a situation CITES was created to prevent.

CITES, a UN organisation, has two core regulatory categories based on listing. Appendix I precludes all commercial trade in the species, while Appendix II requires the exporting country to grant export permits only in cases where doing so would not be detrimental to the survival of that species.

All signatories are mandated to set up a national scientific and management authority that decides on the species needing protection and has the authority to grant permits for import and export.

If the legal wildlife trade is combined with the estimated value of the illegal markets, the annual value of trade in wild flora and fauna would be about $450-billion. (Photo: Supplied)

But there are roadblocks. CITES doesn’t have enough money to function effectively. Its annual budget of $6.2-million derived from membership fees only allows for employing the Geneva-based staff in the Secretariat. It’s not even enough to cover all costs of running the Conference of the Parties every three years.

The result is that assessment is inadequate and protection of species generally relies on often poor national governments or NGOs and philanthropists. Developing countries carry most of the costs of implementing the convention, but get no funding to do so.

Not unconnected is the inadequacy of funds to fight poaching. The illicit drug trade is estimated at around twice the illegal wildlife and timber trade. But the World Bank estimates that just $260-million a year is allocated by governments and foundations to fight this illegal trade, while $100-billion is made available to fight the illegal drug trade.

CITES contains no mechanism for its implementation — it’s left up to signatory countries. It has no enforcement capabilities and relies on member countries enacting enabling legislation and policing.

Many have woefully ineffective controls. Most of the source countries of wild species have inadequately resourced scientific and management authorities, so can’t assess whether export is detrimental to a species. Of the signatory countries, 85 have no dedicated enforcement authority.

It gets worse. Permitting has not been digitised in most countries and relies on national paper-based systems. Permits can be and are copied and forged. Claiming that illegally harvested wild specimens are “captive bred” can be as easy as putting it on the export permit, which can also be reused or “lost” when convenient.

Furniture accounts for about $20-billion of the annual trade in wild flora and fauna. (Photo: Supplied)

And there’s the problem of scale. There are simply too many species registered with CITES to regulate. In 1981, there were just 700 under its protection, today there are 38,700 — and it’s growing.

The Convention uses a blacklisting process that establishes what’s forbidden, not what’s allowed, with the burden of proof lying with those who oppose trade. This involves lengthy debates — often many years long — on the status and listing of each species. With members meeting only every three years, there’s no way assessments can be completed on tens of thousands of creatures urgently in need of protection.

A species waits on average 12 years after being designated as threatened by trade on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List before it gets a CITES listing. In some cases, a CITES listing can take up to 24 years.

Legal exporters and importers of wild products easily circumvent CITES regulations. Despite most of the trade being for luxury consumption, businesses are free-riding and do not have to care about CITES. To them, compliance simply consists of obtaining CITES export or import permits.

The supply chain in endangered species is therefore invisible, so how can CITES or business prove these processes are sustainable?

A new direction

There’s clearly an urgent need for a total reset, and the roadmap has come from an Australian NGO, Nature Needs More (NNM), which found the state of CITES and its part in biodiversity collapse alarming. After an extensive study in which more than 100 stakeholders in conservation were consulted, it has produced a blueprint, Modernising CITES, calling for an urgent overhaul and new principles, which was released on 30 June 2021.

“Without a radical departure from the current state,” says the report’s introduction, “we will not be able to arrest the decline in populations. Without an intact biosphere, human survival will be at risk and without implementing effective protections now, the trend on biomass extraction will make widespread collapse of ecosystems inevitable.”

The difficulty of renegotiating the articles of the convention, it insists, is insignificant compared to the risk of mass extinctions, catastrophic ecosystem failure and food chain collapses.

The Global Assessment Report concludes that about 25% of all animal and plant species are already threatened with extinction. According to NNM, this “makes a mockery of the idea that any of our current practices, including ‘direct exploitation’ or ‘legal trade’, are indeed sustainable. Sustainable use is just a convenient story to keep us from questioning the reality of unsustainable over-exploitation of wildlife.”

(Graphic: From the IPBES report)

The steps being suggested to fix CITES are innovative and far-reaching, but will take a lot of convincing of governments and businesses profiting from the status quo.

It will be crucial, says the report, to start by making no trade in any wild species the default — called whitelisting. This is based on a Precautionary Principle where those wishing to use any wildlife product or species would first have to prove “no harm”, ensure its use is sustainable and pay for research to prove this. CITES would licence and monitor any trade through a centralised digital system, providing a revenue stream as well as end-to-end regulation and real-time monitoring.

Processing of applications would be professionalised and centralised through a listing authority which would set strict rules for applications and evaluate the proposals.

Businesses wishing to use a wildlife product would be grouped with others making the same request and a joint licence would be issued. This would avoid a licence for each end-user and facilitate better management. CITES licencing fees would be set to cover not just the work of processing applications, but also monitoring and enforcement.

Large-scale regulatory frameworks based on whitelisting for market access, says the report, are common in the pharmaceutical and aircraft component industries and these examples would be useful in designing a new framework for CITES. Such frameworks are largely funded by industry and yet keep industry at arm’s length.

A key change in the existing CITES system would be in the Appendix listing. A new Appendix I would afford species the highest level of protection, listing species that simply cannot be traded across international boundaries and may not be used for any form of commercial, educational or scientific exploitation.

It would cover all “rights” over a select number of species and therefore outlaw captive breeding, harvesting, cultivation, hunting, trade, keeping in captivity, use in medical and scientific research and trade in any derived products.

Included in this category would be species granted special status based on non-human rights or cultural significance and those that pose high biosecurity risks, especially in light of future pandemics of zoonotic origin such as Covid-19. Applications for such listings could be submitted by both governments and NGOs.

Fashion accounts for about $15-billion of the legal annual trade in wild flora and fauna. (Photo: Supplied)

The new Appendix 2 listing would be based on whitelisting with the burden of proof of trade sustainability resting with business applicants who would be responsible for all costs associated with producing the required supporting evidence. Until that is approved by CITES, international trade in every wild species would be prohibited.

The listing process would be completely transparent, with listing proposals, hearings, expert submissions and the final evaluation report made publicly accessible. This is essential in order to restore confidence in CITES processes.

All this would require that CITES moves from its archaic paper-based permitting to a global roll-out of an electronic permitting system. Integration with customs tracking would then become easy, using readily available smartphone or scanner solutions. It would also make it harder to launder illegal items into the supply chain.

Compliance would be essential, and the report proposes a framework that ranges from fines to the full suspension of trade.

To achieve the change, says the report, there needs to be a reliable, adequate funding stream for both the central CITES authorities and the national authorities. It notes that the legal wildlife trade is hugely lucrative. The best available estimate for its value is $350-billion for 2016. Of that, seafood earned about $300-billion, furniture around $20-billion, fashion $15-billion and the rest included pets, wild meat, ornaments, jewellery and exhibitions.

If that is combined with the estimated value of the illegal markets, the annual value of trade in wild flora and fauna would be about $450-billion. Charging fees of only 2%-3% of the value of the legal trade would raise at least $9-13-billion a year for CITES to regulate and enforce the legality and sustainability of the trade.

Making it all work will require separate divisions of CITES dealing with listing, compliance, monitoring, enforcement and distribution. These central authorities will work hand in hand with national authorities, with both funded by fees collected from all businesses involved in the trade.

But here’s where it becomes difficult. What will it take to make the transition to a new CITES happen? The first step, says the report, is to table a request for a comprehensive review of the convention and its effectiveness at the next conference in Costa Rica in 2022. This needs two-thirds support from voting parties — that’s roughly 100 countries. Support will be needed from the US, the EU and China as well as most African countries.

To do this, countries will have to take on board the adverse implications of continuing the unrelenting destruction of nature and pursuit of economic growth.

“We haven’t reached that tipping point yet,” says the report, “but ideologies at first die very slowly and then in an instant.

“The proposals presented here need to be thought about and talked about now. When the opportunity for radical change is finally on the table, most players will be familiar with a viable alternative. Then adoption and implementation can be rapid.”

The English version of the report was published on 30 June 2021, and NNM is having it translated into all the official UN languages: French, Spanish, Russian, Arabic and Mandarin. To get the traction it needs a global audience and some deep reflection. It’s the blueprint for saving wild species from a failing system — and us. DM/OBP

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

The annual value of trade in wild flora and fauna is about $450-billion … what a sad story this tells about our ignorance and greed. Spare a thought for all the associated suffering. Let’s hope CITES is transformed. Thanks for Don for your article.

I am exhausted. Imagine what it must be like working for CITES. I think the bell has been wrung. It may be defeatist, but most of the world’s population see no value in wildlife anyway. To try and protect it is to ruin your sanity. We have reached the end of the road

I had the dubious pleasure of attending the 2017 CITES COP in Johannesburg as an NGO delegate and was appalled at the bureaucracy and wheeler dealing. Currently, its just an excuse for thousands of delegates to gather and party while achieving very little. NNM is on the right track but to achieve this it needs a champion with huge stakes in the game. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if South Africa did this and restored its conservation reputation. Over to you, Barbara Creecy !!!

All species should have the same rights as humans.

The elephant in the room of this issue – and I agree that CITES is broken (I’m not sure that it was ever fixed) – is the fact that exploitation of wildlife is an age-old part of human history and remains embedded in cultures. The reason that such exploitation is now completely unsustainable is simply that there are now too many of us, and the scope of exploitation is no longer local, but global. Loss of biodiversity is not yet recognised as a priority by most people, and certainly not by governments. How one gets the issue to the top of the global agenda, along with climate change, poverty, etcetera, and against the inertia of culture, I really don’t know.