OP-ED

Not just an alternative to burial: a brief history of cremation

The practice of cremation, favoured by Hindus, Jains, Sikhs and Buddhists for millennia, but seemingly detested by many others over the years, is often simply held as an alternative to burial. But there’s more to it than that.

Recent images of massed cremation pyres reflecting the severity of the Covid-19 crisis in India have brought global attention to this ancient rite. Delhi’s largest crematorium, the Nigambodh Ghat, which used to require six to eight tonnes of wood daily now needs 80 to 90 tonnes – every single day.

Against this backdrop of smoke and political obfuscation, of bitter flames and exhausted ash, the practice of cremation, favoured by Hindus, Jains, Sikhs and Buddhists for millennia, but seemingly detested by many others over the years, is often simply held as an alternative to burial. But there’s more to it than that.

A man wearing PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) watches mass cremations in a disused granite quarry repurposed to cremate the dead due to COVID-19 on April 30, 2021 in Bengaluru, India. (Photo by Abhishek Chinnappa/Getty Images)

Sarcophagi burn at the cremation site during a Balinese Hindu mass cremation on August 18, 2013 in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. More than 60 corpses were collectively cremated to share the expense of the ceremony. Well known as Ngaben, it is one of the most important ceremonies for Balinese Hindu people, as they believe it will free the spirit from the deceased body so it can reincarnate. (Photo by Putu Sayoga/Getty Images)

It’s not much of a choice though, is it – burial or cremation? However, the idea of choice isn’t much associated with death anyway. We can’t choose to die or not. It’s a done deal. What sliver of choice we might have is to decide upon a healthier lifestyle with less risk. However, whether you smoke and drink or jog under ladders or eat your greens, the manner and the timing of your passing will be something over which you have little choice. No matter what you get up to, it seems, when and how you expire is decidedly uncertain, except in cases of tragic self-will.

Even a healthier lifestyle isn’t much of a choice, and besides, most people can’t choose one anyway. For the most part then, death can visit at any time. On the way to the shops or on the way to the bathroom. Choice and death are only acquainted in macabre jokes and last-meal requests from inmates-on death row.

However, lack of choice doesn’t stop when we do, but extends beyond death, too. For most followers of Islam, Judaism, traditional African religions as well as Christians of different stripes, inhumation (a fancy word for burial) is preferred, even mandatory, while cremation is strictly taboo. Why?

For these faiths, burning a corpse is understood to be a defilement of the body, which is regarded as the temple of God, a holy vessel animated by a divine spirit which departs upon death, perhaps to return. One does not tamper with God’s creation, is the prevailing belief. The Prophet Muhammad taught that to break a man’s bone in death is the same as to break it in life.

The body, made in God’s image, must therefore be kept intact for all sorts of afterlife activity. In an article, “Cremation Threatens Zimbabwe’s Ancestral Spirits”, former vice-chancellor of The University of Zimbabwe Gordon Chavunduka summed it up like this: “If the body is cremated, that spirit would be blocked. Although it would remain alive, it would be angered that traditional burial rites had not been followed properly and could return to punish the family and community.”

This is the story elsewhere in Africa, too. Local theologian Maake JS Masango acknowledges the same in “Cremation a Problem to African People”, where he foregrounds the problem of dwindling space for burial and somehow makes a case for change, with Biblical reference.

With not much land suitable for burial and sacred burial rites remaining inflexible, it’s urban planners and local governments that are becoming vexed the world over, while no one dares offend. Meanwhile, burial costs are rising. Burials are considered vastly more environmentally damaging than cremation, even with tightened furnace emission standards.

In Beijing, for example, where cremation is encouraged, a grave plot costs more per square metre than an apartment. In some German cities, gravesites must be leased, not bought, and bones disinterred and bundled up by a specialist when the lease expires, whereafter the information on the headstone is inscribed on the skull and placed in a crypt.

Susan Brice, director of cemeteries for the City of Cape Town, identifies lack of space as the biggest threat to the future of burial practices – as it’s been for the past 20 years. In an interview for my podcast, How to Die, she tells how this issue doggedly remains in the number-one spot on the agenda for each annual conference of the South African Cemeteries Association.

Cape Town, by the way, has about a 20% cremation rate, and although I think this information is out of date, it’s considerably higher than anywhere else in South Africa. Why? Lots of heathen ex-surfers, apparently, although Hindus, Catholics and Protestants are also quite happy to be cremated. The latter, especially, seem to have gotten their heads around the “from dust you came and to dust you shall return” thing quite early, to include ashes, while the Catholic Church only sanctioned cremation as recently as 1963, although it discourages the scattering of remains. For Catholics and many other Christians, and people in other faiths, too, it seems that culture and class can play more of a determining role than faith in the decision to cremate or bury.

But things can change and do. An interesting example is related in the consistently excellent 99% Invisible podcast, in an episode called “Life and Death in Singapore”. This tiny island, which takes 45 minutes to traverse in a car (with traffic, nogal) has a cremation rate of more than 80%. But it used to be 10%, about 50 years ago. So what happened?

In 1973, the Singaporean government decreed there would be no more ground burial at more than 70 cemeteries, due to lack of space for the living – the cemeteries were simply too big, some with gravesites 30m wide. Housing needed to be built, choices made, the living privileged over the dead. More than 100,000 bodies were exhumed and cremated from the largest cemetery alone, Peck San Theng, which was reduced to just 8ha from an original 324ha.

As you might imagine, this decision wasn’t widely welcomed, and although 50% of the interred bodies were claimed, then cremated and memorialised, the other half were not, and were cremated together and scattered solemnly at sea. (Perhaps this demonstrates that despite an avowal that burial is necessary, in many places, I think it’s a truism that graves tend to become neglected over time, within a generation or two, and then fall into disrepair. I think the German cities who lease grave space understand this.)

In Singapore, ancestor veneration was part of many religious practices on the island, which has been recognised as the most religiously diverse in the world. Here, then, it seems that choice was once exercised, then bluntly removed. The remaining land in Peck San Theng includes a new columbarium – a building for funerary urns, which was then without local architectural precedent. The same vigils and rites for the dead are now carried out in these narrow corridors perfectly well. People adapt.

People search for their loved one’s urn at the Bright Hill Crematorium & Columbarium during the Qing Ming Festival on April 4, 2013 in Singapore. (Photo by Suhaimi Abdullah/Getty Images)

Incidentally, in 2007 the Singaporean government sorted out burial problems at the remaining state-run cemetery where inhumation was still permitted. Buried people are interred in a grid-like set of crypts which must be evacuated after 15 years, consistent with the Islamic practice of recycling graves, whereafter remains will commingle.

This is similar to practices in modern Greece, where you have to pay good money to keep people in the ground, and exhume at your own expense, too. The first and only crematorium in Greece was built as recently as 2018, and is privately owned. There’s also a new crematorium in Israel, after the first was burnt to the ground by Ultra-Orthodox Jews in 2007, and which now operates from a secret location.

Ironically, it was the Greeks (but of the ancient variety) who favoured cremation as a way of honouring warriors slain in battle and repatriating their remains from distant lands many thousands of years ago. (Today, sending human ashes by courier is tricky and exorbitant, in the region of R15,000 on a popular route, at least double your average plane ticket. Can you imagine the paperwork at Home Affairs? That alone might be enough to kill you.)

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, “cremation [for the Ancient Greeks] became so closely associated with valour and manly virtue, patriotism and military glory that it was regarded as the only fitting conclusion for an epic life”. Early Romans adopted the habit, and although burial was still a popular option, they are credited with building the first columbaria. Now there’s a word you don’t hear every day.

Crematory practices in Europe soon declined with the spread of Christianity. Cremation became not only forbidden, but regarded as appropriate punishment for heretics, similar to burning at the stake.

Some people the church considered particularly nefarious, such as the dissident theologian John Wycliffe, were exhumed and posthumously punished with cremation, his body rendered to ash and scattered into a river to prevent any further corrupting influence. I suspect that the flames of cremation and of Hell were seen as one and the same, and in some places, still are.

Although there is plenty of evidence for cremation preceding the Ancient Greeks and Romans everywhere from Russia to Australia, it was the Italians who were responsible for the resurgence of crematoria in the modern era. A revolutionary furnace design by Ludovico Brunetti, shown at the Vienna Exposition in 1873, caused a sensation. The world’s first custom-built crematorium soon opened in Milan in 1876 and later the same year in Washington, Pennsylvania, where it was believed that “decomposing bodies” in local cemeteries were contaminating the water supplies and making the citizens sick.

This growing movement for the reintroduction of cremation in the 1870s contained vocal proponents of the “miasma theory”, which held that cremation would negate the foul air that caused disease. Although advocates of cremation at the time were all for its cleansing attributes and the idea of the purifying flame, they identified strongly as a secular intellectual movement that sought practical alternatives to the problems associated with burial at the time – namely, to “prevent premature burial, reduce the expense of funerals, spare mourners the necessity of standing exposed to the weather during internment, and urns would be safe from vandalism”.

Cremated remains that were added to the concrete of an artificial reef unit are lifted to be placed underwater in this undated photo from Eternal Reefs, Inc. The Atlanta-based company allows the deceased to spend the afterlife as part of an artificial reef, which serves as a home to fish and other marine life for at least 500 years. The Memorial reefs are deployed to permitted locations at sea where they are most ecologically needed. More than 1,500 different reef sites have been created worldwide. The sites are approved in areas designated appropriate by federal, state and local governments and are dedicated as permanent memorials while also bolstering natural coast reef formations. (Photo Courtesy of Eternal Reefs/Getty Images)

Cremated remains that were added to the concrete of an artificial reef unit are seen underwater in this undated photo from Eternal Reefs, Inc. (Photo Courtesy of Eternal Reefs/Getty Images)

Cremation is undoubtedly a cheaper and cleaner and more efficient way to dispose of bodies. Local prices for a “direct cremation” (the body straight to the crematorium soon after death, without a memorial service) are around R8,000 – although curiously, in this industry, you’ll get charged according to your socioeconomic status, I’m not sure why. Alternatively, you could have a more expensive “attended” or “unattended” cremation, which means the deceased is in a casket at the memorial service, or not.

In Japan, 99% of people are cremated, and elsewhere in the world, especially Switzerland, Canada and The Netherlands, it’s way more than 50%. In South Africa and the rest of the continent, cremation is a minority practice. It seems that it is still regarded as sinister, an attitude helped by superstitious misconceptions and conspiracy, the most common of which is that “the ashes are all just mixed up”. But why would they be? Do people think that the dead are not respected in crematoria?

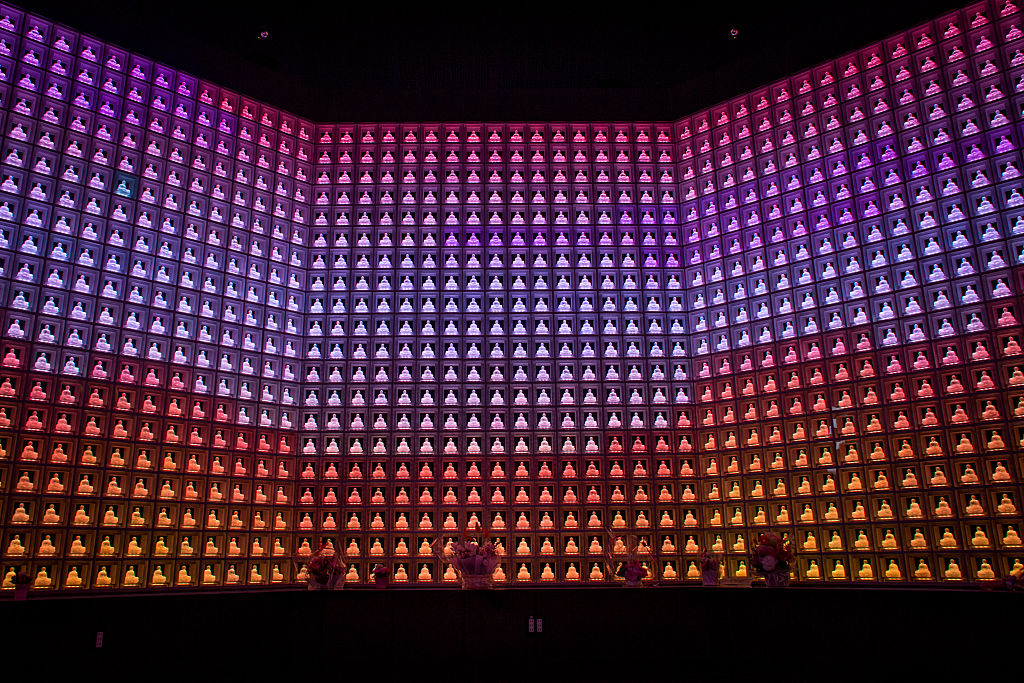

Flowers are seen placed in front of lit glass Buddha statue alters inside the Ruriden columbarium on April 6, 2015 in Tokyo, Japan. The Ruriden, operated by the Koukokuji Buddhist temple, took two years to build and houses 2046 futuristic alters with glass Buddha statues that correspond to drawers storing the ashes of the deceased. An IC card allows the owner of the alter to access the building and lights up the corresponding statue. The ashes are stored for 33 years before being buried below the Ruriden, currently 600 alters are in use and another 300 are reserved. (Photo by Chris McGrath/Getty Images)

In fact, the process is highly regulated, and each corpse is provided with a unique marker, usually made of a firebrick or a metal that won’t melt at 1,000 degrees. Afterwards, this is located among the burnt remains, verifying the body which was cremated, which is now about 2.5% of its former weight. The remains resemble not pure ash but ash mixed with bits of disintegrated bone, which are further ground up in something called a cremulator, which looks just like a giant coffee grinder.

For cremation, the deceased is placed in a combustible coffin and loaded up in something called a retort – that’s the chamber in the cremator. I’m struck by the lovely choice of word – retort, meaning to “make return in kind” (from Old French retort and directly from Latin retortus, “turn back, twist back, throw back”.)

After the retort is “charged” with the deceased, incineration takes a couple of hours. Besides ashes and bits of bone, there may be some melted metal from fillings or jewellery that’s been missed, casket furniture (those horrible metal handles on coffins) and the odd surgical implant, like the titanium along my shoulder blade. The body organs vaporise, as do breast implants, but pacemakers can cause serious explosions.

And here’s where choice finally kicks in! What kind of “cinerary urn” would you like?

Designer Hazel Selina displays her ”Ecopod” environmentally friendly coffin, and an ”acorn” papier mache urn for cremation ashes April 8, 2001 as part of the ”Day for the Dead” event at The Natural Death Centre in Cricklewood, North London. The coffins and urn reflect a growing demand for environmentally sound funerals. (Photo by Sion Touhig/Newsmakers)

This is definitely something that can be acquired beforehand and stored in the garage. Some people get cremation jewellery made – and here, too, you have choice. Heck, you can even choose what colour your “ash scattering rocket” might be – a projectile which shoots up into the atmosphere and disperses you up there in the clouds. And if you’re really feeling sentimental, of course you can mix your ashes with your loved one and get an hourglass made, even though it will not tell accurate time.

Who said cremation couldn’t get creative? Given all these little bells and whistles, it’s a no-brainer why more and more people are getting cremated. It’s practical, and a growth industry around the world – just not here, it seems. And hey, it’s not just about lack of space, it’s about outer space! If you want, you can send some of your ashes into the galaxies where you came from – if that’s what you believe. Although by the time you die, who knows, your beliefs may have changed. DM/ML

Original design by Jade Klara

Sean O’Connor is an End-of-Life Carer (“death doula”) and hosts the How To Die podcast on Apple and Spotify.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Most fascinating. Thank you.

Seven billon bodies and counting to burn every 60 years or so; that around 300,000 every day. O o o the carbon cost (not to mention all the trees chopped down)! But there’s more to it. In the 1980s a bunch of Cambridge architectural students attempted to design an completely self-contained home. They found the most noxious thing they would have to find a way of disposing of was the human bodies. Best is return our bodies to the soil (aka star dust), but not in hard casks, rather paper, cardboard or linen, so it gets composted chop-chop – and plant a tree on top, either fruit or flowering (indigenous is always best). Let’s start a business, call it The Snuff Box.

maybe the best would be to go out with a bang and beauty. buy a few or many rockets, mix in ashes with the other stuff. light them, hear the swish and see them decorate the night sky. maybe do it all together as a festival. festival of lights and the dead.

In ancient India, in Buddhist practice, bodies were simply placed in distant sites so that the wild creatures that eat meat would have food. I can see no reason why sites in our mountainous areas could not be set aside for those who would like to be food for the rest of the world.