WELLNESS

Health tips: Languishing in a time of corona

If you’ve been feeling lethargic, foggy, unproductive and unmotivated, you might be languishing. And you are not alone.

Coined in 2002 by American sociologist and psychologist Corey LM Keyes, the psychological term “languishing” has recently made a comeback. Featured in a highly shared article in The New York Times by Adam Grant, organisational psychologist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, the term might explain the exhaustion and general mental lethargy felt worldwide after more than a year of a harrowing pandemic.

What exactly does it mean?

There are five definitions of the word in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary: 1) “to be or become feeble, weak or enervated”, 2) “to be or live in a state of depression or decreasing vitality”, 3) “to become dispirited”, 4) “to suffer neglect”, and 5) “to assume an expression of grief or emotion appealing for sympathy”.

All of these are seemingly encompassed by Keyes’s use of the word as a category for a state of mental health, which he succinctly refers to as “the absence of mental health”, the absence of wellbeing.

The saying goes that the opposite of love is not hate (because these emotions have a similar relationship to strong, passionate reactions) but indifference. The opposite of love is feeling nothing.

Similarly, languishing is not exactly feeling bad, it’s just not feeling good. It’s indifference. As Grant describes it, languishing is the feeling of “meh”.

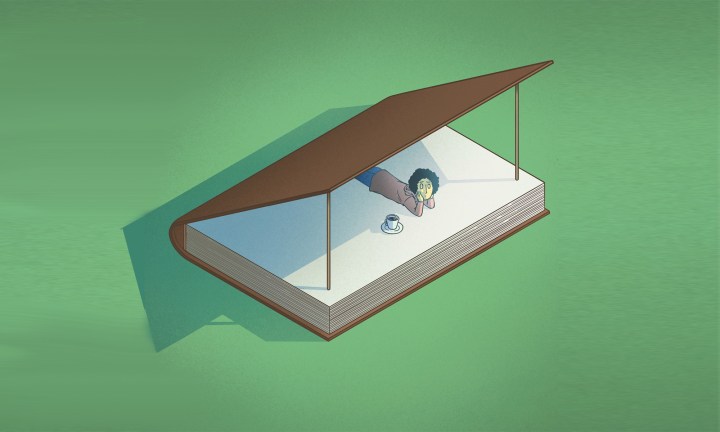

He says “languishing is a sense of stagnation and emptiness. It feels as if you’re muddling through your days, looking at your life through a foggy windshield.”

If mental health is thought of on a spectrum from depression (feeling despondent, drained, worthless) to flourishing (having a strong sense of meaning, mastery and mattering to others), languishing is “the neglected middle child of mental health. It’s the void between depression and flourishing”.

It may manifest as a foggy feeling, exhaustion or an inability to concentrate, which, of course, would dull motivation and disrupt your ability to focus. Perhaps you are having a hard time concentrating on your work from home, or feel totally unmotivated to get outside for fresh air. The absence of wellbeing, languishing, can be harmful in many parts of your life.

Why are we talking about it now?

The Covid-19 pandemic feels as if it has been dragging on forever. Every time we think we are out of the woods we get knocked down by yet another wave of sickness and disaster. Not to mention the other wild things that have happened since March 2020. It seems especially strung out in South Africa, while other parts of the globe (the US and Britain) are seemingly on the path towards opening up completely.

The main focus has been on the bodily illness of Covid-19, the symptoms and deaths rather than their undeniable effect on our mental health. In a sense we have been communally traumatised: it feels like no one has escaped unscathed from the clutches of the pandemic. If you think about the chronic stress that we have been living with for more than a year, it follows that we are all totally exhausted.

In a podcast, Feeling Foggy? It’s Not Just You, featured on NPR’s Life Kit series, correspondent Rhitu Chatterjee explains that there are a variety of reasons that this is true.

First, when we go through disaster situations, our brain (specifically the amygdala, which manages our reactions to panic) puts us into flight-or-fight mode. We are on high alert, or “hyper vigilant”.

“When you have increased vigilance your body basically uses more energy. For more than a year your body has been using more energy being vigilant. Obviously, that leads to the feeling of tiredness.”

Chatterjee also points out that “chronic, consistent stress causes low-grade inflammation”, a fact proven in this 2019 study. This subtle, barely noticeable inflammation will, in the long run, cause fatigue and have negative effects on mood.

Stress can also have a drastic effect on sleep patterns. A study titled “Chronic stress undermines the compensatory sleep efficiency increase in response to sleep restriction in adolescents” demonstrated that it wasn’t so much the hours that the teenagers in the study slept that affected their cognitive capability, but the quality of their sleep, which was eroded by exterior and controlled stress factors. Further, this 2020 study showed that stress, sleep disruption and heightened depressive symptoms often go hand in hand.

The bottom line is that when we are stressed we sleep less efficiently (whether little or too much), which leads to exhaustion and sometimes even more stress.

It makes almost startlingly clear sense that in these later stages of the pandemic, where the virus itself has lost a lot of its terrifying mystery, our tense, fight-or-flight panic mode is being replaced with exhaustion, indifference and “meh” – the chronic condition of languishing.

This non-wellbeing is not to be taken lightly. As Grant points out, people who are languishing now have a high probability of falling into depression or mental illness in the coming years. This might be because an absence of mental health is a lot harder to pinpoint, define and take steps to alleviate than a presence of mental illness. To Grant, languishing means “you’re indifferent to your indifference”, and this is a very slippery slope.

In fact, this 2002 study showed that “the risk of a major depressive episode was two times more likely among languishing than moderately mentally healthy adults, and nearly six times greater among languishing than flourishing adults”.

So…

What can we do about it?

According to Grant, just giving it a name, a definition, might help people who are languishing. “It could help to defog our vision, giving us a clearer window into what had been a blurry experience. It could remind us that we aren’t alone.”

Just knowing that you have a name to put on your feelings, one that others might share, will help you to be mindful about things in your life that make you feel better, or take steps towards allowing yourself to flourish.

These steps might include, as Chatterjee puts it, “the usual bucket of coping strategies”, typical strategies suggested for nurturing wellbeing, such as exercise, being outside, exposure to nature, healthy eating and social support.

They might also include what Grant calls flow time – doing an activity that completely absorbs you. True flow time should feel something like what this writer (a non-meditator) can imagine meditating would feel like; your sense of time, place and self melt away – there is nothing else on your mind but the task at hand. Unlike classic meditation, flow time can look very different for different people. It could take place playing an instrument, or knitting, or, as Grant suggests, playing a word game on your phone. As long as the activity has your full focus.

If you are struggling with a slump in productivity, Grant suggests working a few hours of uninterrupted time into each day. According to this study by a software company in India, the productivity of its employees went up 20% when the company made it a policy for them to spend a few hours of uninterrupted time on one task every morning. People are much more productive if you concentrate on one thing at a time.

Which is important because a sense of progress is one of the most essential factors in daily joy and motivation. If you can get something done, even if it’s small, it will help your mood immensely.

Which brings us to another tip that Grant imparted: create small, achievable goals and stick to them. He suggests goals of “just manageable difficulty”, not too hard that they are impossible and will leave you feeling defeated, but hard enough that they are challenging. Aim for goals that “stretch your skills and heighten your resolve”.

Having an appreciation of the smaller things in life can extend past goals and tasks. Chatterjee suggests that savouring and celebrating small things and practising gratitude can have a positive effect on our wellbeing – sentiment backed by this study in 2003, in which randomised groups of people wrote out either their burdens and complaints, or what they were grateful for. It found that “the gratitude-outlook groups exhibited heightened wellbeing across several, though not all, of the outcome measures across the three studies, relative to the control groups”. In layman’s terms, actively practising gratitude might very well help alleviate feelings of “meh”.

Finally, Chatterjee suggested making some kind of change. It’s been a long year with more than the usual number of toils. Maybe we should all try something new. Keyes agrees, suggesting that the key to wellbeing is an interest in life. The pandemic has been hard because many of us have not been able to pursue our interests. “The first key to feeling good about life is to seek out new interests.”

If you think you are languishing, like a lot of us, these are a few small steps that might help you get out of your slump. That said, if you fear that you are slipping into depression, or any other kind of mental illness, please contact a professional healthcare worker or psychologist.

Chatterjee also reminds us that once things get back to normal, we will bounce back. “What we know from tons and tons of research into how people react to traumas, things like terrorist attacks or natural disasters, we know that over time the vast majority of people will bounce back. There is tremendous human resilience in us. As we gradually return to normalcy, most of us will be able to bounce back.” DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

An excellent and practical article. Thank you! Now I have a useful name for that meh!

Amazing that I came across this article just as I was feeling so incredibly “meh”. Thanks DM, some incredibly useful tips here.

Great article! I live in a retirement complex and everyone is holed up in their apartments. Those that keep themselves occupied with activities such walking outside, drawing , knitting , seem to be in a better space than the ones who are watching tv 24/7. The bad weather adds to the “ meh” feeling , but

even a few stretching exercises helps.