OP-ED

Monty Naicker and the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign — ‘memory against forgetting’

Seventy-five years ago this month, The Natal Indian Congress, led by Dr Monty Naicker, launched its campaign of passive resistance as a protest against the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act which excluded Asiatics from the occupation of controlled areas in and around Durban.

Selvan Naidoo is a board director of the 1860 Heritage Centre. Kiru Naidoo is the author of Made in Chatsworth and adviser to the UKZN Special Collections. The authors will launch a pictorial book later this year to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign.

The tortuous question of land in South Africa is an emotive issue that touches at the heart of its people. The world over from Kumari Kandam to Aleppo to Jericho to displaced settlements like District Six, Sophiatown and Magazine Barracks, disputes and wars have been contested and are still being fought over land and territory. The potential danger that this dispute poses may very well lead to an implosion of our beloved country if historical redress and sensitivity are not managed appropriately some 27 years into our democracy.

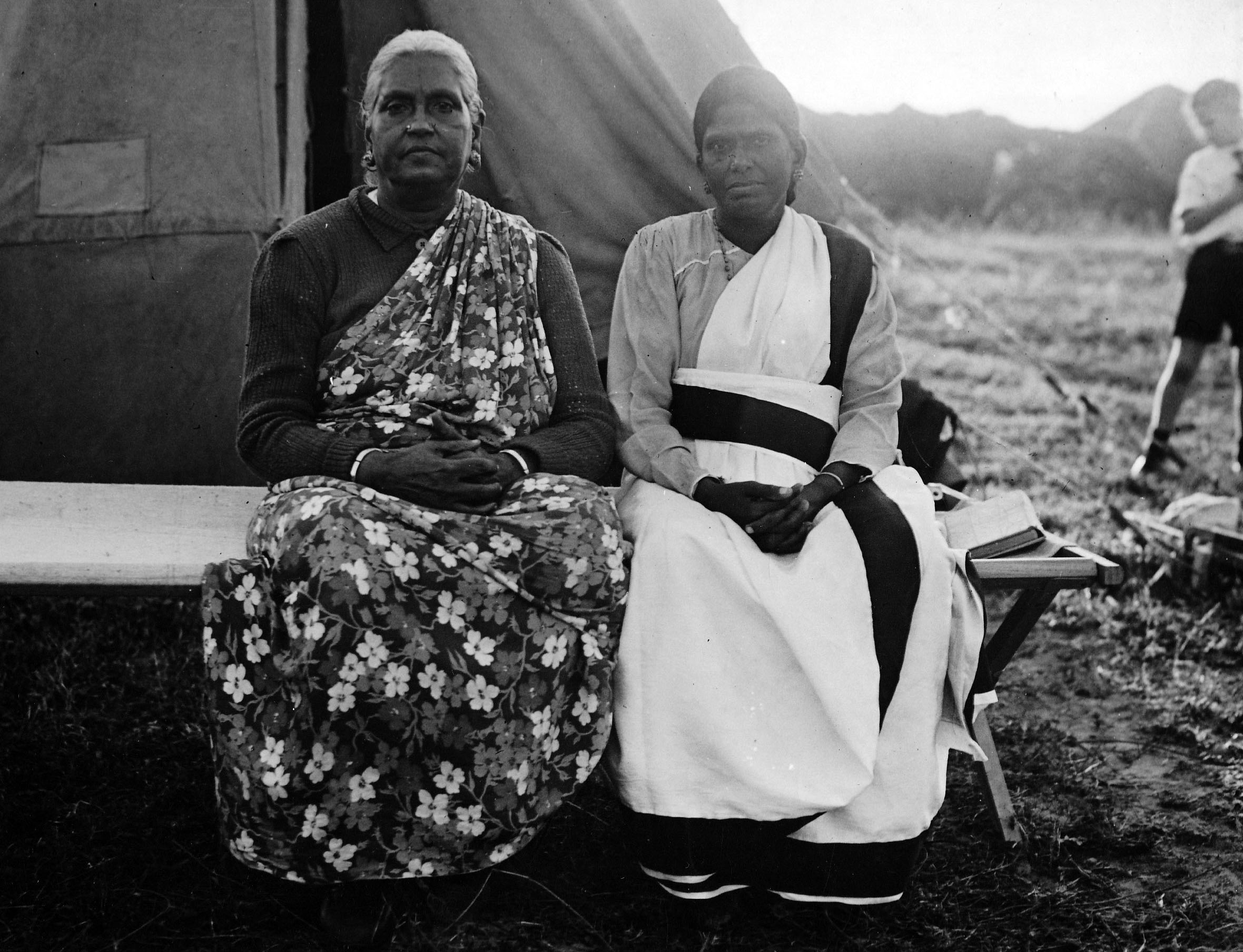

Passive resister Gadija Christopher and Dr K Goonam at the Passive Resistance Campaign of 1946. (Photo: SS Singh Collection)

In narrowing our focus to this question of land dispute, we turn our attention to our ancestry of indentured workers who arrived here in 1860 to grow the ailing colonial economy of KwaZulu-Natal. Sunday, 13 June 2021 marked the 75th anniversary of the passive resistance campaign of 1946. The Natal Indian Congress launched its campaign of passive resistance as a protest against the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act which excluded Asiatics from the occupation of controlled areas in and around Durban.

Before this, the main areas that Indians occupied were beyond the Umgeni River, in Riverside and Prospect Hall and further inland at Duikerfontein and Sea Cow Lake. Springfield and Sydenham were also predominantly Indian. Indians also settled in areas such as Mayville, Cato Manor, Clairwood and Magazine Barracks, and the Bluff.

Even though informal segregation existed at this time, it was not until 1922 that the first major restriction came about when the municipality reserved the right to exclude Indians from purchasing any municipal land. The Slums Act was passed in 1934 to improve conditions and to facilitate “slum clearance” within the city.

Behind this veil, the Slums Act factually meant the expropriation of Indian property. The municipality’s rationale for this expropriation was cleverly masked as the city’s cleanup and industrial expansion. Ironically, as late as the 1970s Indians in places such as Tin Town in Springfield still lived in shacks without basic services.

By 1936, only 20% of Indians owned houses in Durban that were made of brick, stone or concrete; the rest lived in wood and iron structures. The colonial government did not provide electricity to these residents as they did not trust that the Indians could handle it.

The 13th of June 1946 was declared as Hartal Day when 20 Indians began the Passive Resistance Campaign on Thursday night by pitching five tents on vacant land in a controlled area at the junction of Gale Street and Umbilo Road and camping there. This group of 20 men, under the command of Dr GM “Monty” Naicker, chairperson of the Natal Indian Congress, kept the strictest discipline. Dr Naicker remarked that if and when he and his men were arrested or removed from their camp “another 20 would move in to take their places”.

Monty Naicker and fellow passive resisters set up tents at Umbilo, Durban in the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign. (Photo: SS Singh Collection)

A few years earlier the Pegging Acts of 1942-43 gave the government the right to remove and destroy shacks and homes in some areas under the pretext of improving unsanitary living conditions. By 1946, the Passive Resistance Campaign became a major focus of Indian community activism to contain the aforementioned “Indian penetration”.

The Ghetto Act paved the way for the Group Areas Act passed in 1950, which proclaimed large parts of previously owned and occupied black areas to be now exclusively occupied by white residents. This meant that the communities who were not classified white who found themselves in these areas would have to be moved to other areas designated as “Indian”, “coloured” or “African”.

The Ghetto Act caused a major uproar and led to the two-year Passive Resistance Campaign from 1946 to 1948 when several thousand Indians courted arrest. Despite the protests, the act was passed in 1948. The Group Areas Act formalised the process of separate development. By 1950, the Group Areas Act displaced thousands of Indians and Africans from their homes and businesses.

Indians were removed from areas such as Mayville, Cato Manor, Clairwood and Magazine Barracks, and the Bluff. By 1950, there were adverts in the newspapers for an exclusively Indian suburb called “Umhlatuzana”. Later, Red Hill and Silverglen (later Chatsworth) were also advertised. Reservoir Hills, which was also declared an Indian area, was available for the more well-to-do Indians. In the north of Durban, La Mercy and Isipingo Beach were also designated Indian areas. In Merebank, purpose-built houses replaced the poor settlements and by the late 1950s, a reconstructed Merebank offered cheap houses for which the purchaser had 10 years to pay.

Passive resisters from the 1913 Gandhi-led strike at the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign. (Photo: SS Singh Collection)

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign, the Sites of Struggle Collective marked the 75th anniversary of the 1946 passive resistance against racial segregation on Sunday, 13 June 2021 in Chatsworth.

Collective spokesperson Zandile Qono, whose family was a key part of the campaign, pointed out that the current generation needed to honour the history of the Struggle for a nonracial society. “Our activism must serve as memory against forgetting that people lost their lives, went to prison, were thrown out of their homes and had their lives destroyed by a racist government,” said Qono. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.