OP-ED

When genocide hits home: My hometown was an integral part of Canada’s attempt at cultural erasure

The discovery of the remains of 215 children in the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Reservation School in western Canada confirmed what that country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission had concluded: The school was part of a cultural genocide committed against Canada’s Indigenous People. Growing up in Kamloops, I must have driven past the school’s impressive main building, made of local red brick, with its granite chimney and stone details, hundreds of times.

Dr Terence McNamee is a Global Fellow of the Africa Program at the Wilson Center (Washington, DC), based in Johannesburg.

Nothing prepares you for the moment your hometown becomes infamous.

On 28 May 2021, news broke that the remains of 215 children were discovered buried in the grounds of a school in Kamloops, a former “pulp and paper” town of about 100,000 people, nestled in a wide valley at the confluence of two branches of a large river that runs through the southern interior of British Columbia, Canada’s westernmost province.

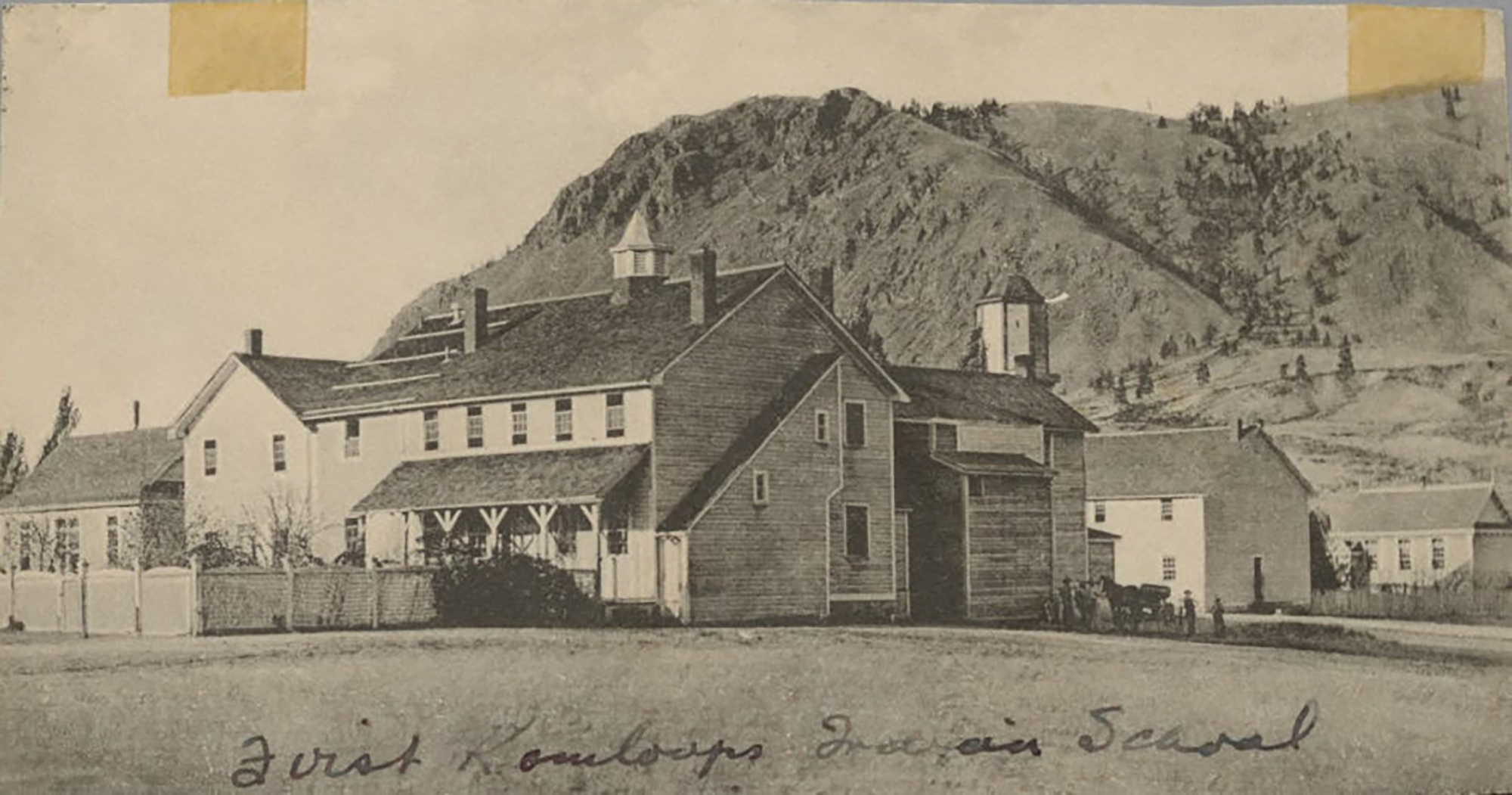

The school — the Kamloops Indian Reservation School — was opened in 1890 and operated as a boarding school for Canadian Indigenous children until 1969. For a time, it was the largest of more than 130 residential schools established across Canada by its federal government in the late 19th and first-half of the 20th century, to which as many as 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit (groups of Canadian Indigenous people) children were forcibly sent. It was run, like roughly two-thirds of schools in the residential system, by the Catholic Church. The rest were administered by Anglicans, Presbyterians and other Christian faith groups.

Growing up in Kamloops, I must have driven past the school’s impressive main building, made of local red brick, with its granite chimney and stone details, hundreds of times. As a toddler in the early 1970s, I splashed about in the school’s outdoor swimming pool with my brothers and sisters. Today my nephews play football on the surrounding fields. On a mountainside golf estate overlooking the school, my parents can sit on their balcony on summer nights listening to drummers and singers from the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc band (‘band’ is a Canadian term for First Nations communities). Band members gather on the adjacent Pow Wow Grounds to create sacred harmonies linking their ancestors with the heartbeat of Mother Earth.

The shocking find in Kamloops, revealed after the local band hired a private firm to use ground-penetrating radar on the site, confirms what Canada’s own Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) concluded in its final report published in 2015: the school was part of a cultural genocide committed by the federal government against Canada’s Indigenous People. Elder members of the band were not shocked; they had been talking about missing friends or siblings for decades. But no one was listening. Or no one cared. The discovery of the buried children, some as young as three years old, has changed all that.

***

Canada’s TRC was established in 2007 in the wake of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the largest class action settlement in Canadian history, resulting in more than $3-billion paid to claimants. For the next six years, the TRC travelled across Canada and heard from more than 6,500 witnesses about their experiences as students or relatives of students who attended residential schools. The TRC’s final report included 94 “calls to action” (or recommendations) to further reconciliation between Canadians and Indigenous People.

One nationwide study conducted at the start of the TRC hearings suggested that fewer than 5% of Canadians were aware of the brutal history of residential schools. By the time the final report was published, awareness levels had risen to roughly 60%. Today, no one asks why former students are called “survivors”.

An undated photo of the Kamloops residential school. (Photo: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

Once mandatory attendance became law in the 1920s, Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families. Parents could be jailed for refusing to let their sons or daughters be taken away. Once boarded in their new schools, children were prevented from speaking their native language or practising their own spirituality and customs.

Physical and sexual abuse by their church-run staffs was common. So too was tuberculosis, malnutrition and other diseases resulting from poor living conditions. In the 1940s, death rates within residential schools were up to five times higher than among Canadian children as a whole. Conditions at one school on Canada’s western coast were so harrowing that it was known as Alcatraz; at another school, 3,000km to the east, a makeshift electric chair was used by school authorities as a form of punishment. Survivors have recounted incidents of suicide and murder. Across the country, many children ran away from their schools and vanished. Some froze to death or drowned while trying to escape.

All this in the name of assimilating indigenous children into Canadian society. For much of the 20th century, this is how federal officials would explain why the residential school system was established: assimilation. Its aim is described less politely today: “to kill the Indian in the child”.

Between 1900 and 1950, “Indians” comprised roughly 1% to 2% of Canada’s total population. Compared to its big projects of nation-building in the 20th century — bridging the French-English divide, throwing off the British imperial yoke — Ottawa’s attempt to eliminate Canada’s original inhabitants as distinct peoples was a (monstrous) sideshow. Government officials told themselves that their goal was to bring Canada’s Indigenous minority — brought to heel by disease, conquest and various treaties in the previous century — into the modern, Euro-Christian-based world. This would justify, in no particular order: the dismantling of traditional governmental and legal systems; various forms of social engineering, from forced sterilisation to population removals; denial of basic rights; repression of culture and language; destruction of family units.

From here, an unbroken line stretches to the present day. Canada’s First Nations, Metis and Inuit are disproportionately represented in most indicators of a miserable life: they have vastly more children in care facilities, more youth committing suicide, more adults in the criminal justice system, more women being abused, more alcoholism, more homelessness, more unemployed. The intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous Peoples with its attendant psychological and social problems, not least a collective loss of pride and self-respect, was amplified by Canada’s unwillingness to face up to its past for decades. Survivors and families finally given a chance to share their stories publicly during the TRC did so at great cost: the reliving of hell.

The news from Kamloops has exacted a similar toll. The former chair of the TRC, Senator Murray Sinclair, an Anishinaabe and a member of the Peguis First Nation, received hundreds of calls from survivors in the days after the unmarked graves were found. “I just sit and listen while they cry.”

Formal inquiries into historical crimes tend to privilege one kind of death: state-sanctioned murder. Madeleine Fullard knows this better than anyone. She is the head of South Africa’s Missing Persons Task Team, established in the wake of its own TRC, to investigate political cases of missing persons from the apartheid era. In recovering the remains of more than 160 people over 15 years, Fullard has stared into still-deeper pits of inhumanity: the thousands of men, women and children who died as paupers. Displaced and neglected, their lives torn asunder by a racist system, they ended up in the same unmarked soil that Fullard’s team has had to sift through to find the “important” victims.

As in South Africa, there was a hierarchy in death in Canada. Lives not valued ended up under orchard fields or football pitches. The “exhumation” of unidentified remains, Fullard explained to me, “is an act of reinstating citizenship”: you will not be lost forever, your life mattered. She notes that 20 years after 9/11, forensic experts are still trying to identify every fragment of human remains found at the site of the attacks in New York and Washington. Work on the more than 1,000 victims who still need to be identified will continue for years. Their relatives can find some consolation in knowing that they have not been forgotten. Healing in Canada will require the same commitment to its missing.

One of the six volumes in the final report of Canada’s TRC is titled “Missing Children and Unmarked Burials”. The commission found that at least 3,200 children’s deaths were registered at the schools — the last of which closed in 1997 — amounting to one in every 50 students enrolled in the residential system during its existence. For around half of those registered deaths, no cause is given, and for a third, the name of the student was not recorded. But since the commission ended, Sinclair believes that the true number of students lost is likely much higher. Based on survivor testimonies, huge gaps in available records, and similar practices at Indigenous schools not considered under the TRC because they were run by provincial governments or religious orders without federal support, he estimates that it could be five times that figure.

Canada is bracing for more anguish.

Experts and survivors have been saying for years that surrounding many of Canada’s worst Indigenous schools lie cemeteries of missing children. “Subjected to institutionalised child neglect in life, they have been dishonoured in death,” the TRC report acknowledged. Families that have struggled without closure or resolution, clinging to the faintest hope that their loved ones are alive, somewhere, are caught in a vortex of loss.

Margaret Randall captured this type of trauma well in her poems on Argentina’s Dirty War. “Disappeared” became a transitive verb in Argentina to describe how the military junta dealt with more than 30,000 political opponents — many of whom were thrown out of planes into the Atlantic Ocean during so-called “death flights” — in the 1970s and 1980s. Randall’s poems spoke to the desolation experienced by families of the missing. She writes in As if the Empty Chair, “We cannot move on, for where would they find us when they stumble home?”

Kamloops is thought to be the tip of an iceberg. So shot through is Canada’s horror and shame, an accelerated national effort to determine who died, how they died and where they are buried is sure to follow. Technology can help provide some of these answers. But it is of no use in tackling the baser question: why did Canada, long seen by other nations as a beacon of fairness and decency, look away for so long?

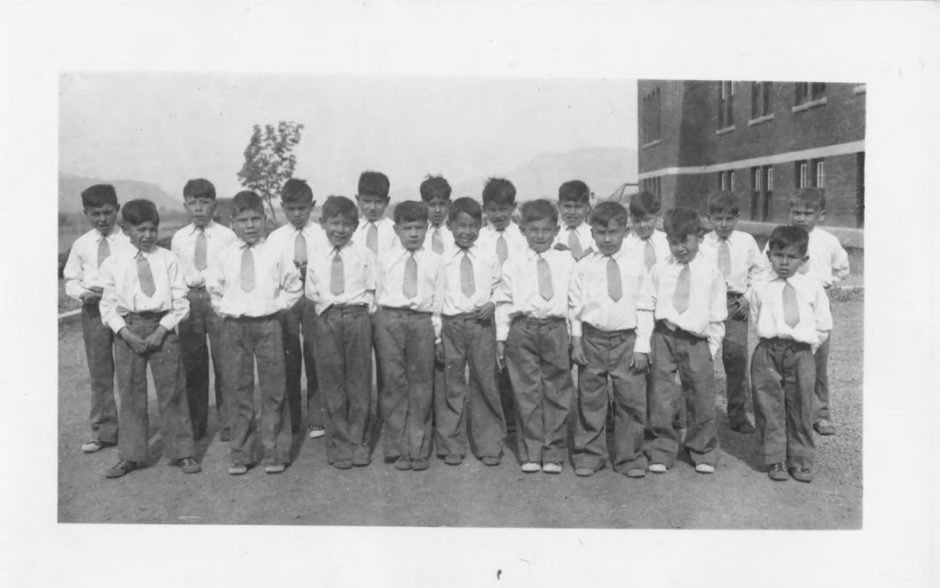

Male students at Kamloops residential school in 1944. (Photo: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

***

For 20 years after the end of World War 2, Germans tried to forget the Holocaust and other horrors inflicted by the Nazis. It was the children and grandchildren of Germany’s wartime generation, influenced by the film and literature of the time, and leaders like Willy Brandt who in 1970 fell to his knees in front of a memorial for the Jewish Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, asking forgiveness for Nazi atrocities (in which he played no part), who drove the sweeping working-through — or processing — of the country’s past known as Vergangenheitsbewältigung.

Susan Neiman, in her book Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil, hails the courage of this vanguard, who older Germans disparagingly called Nestbeschmützer or “nest-foulers” for digging up history that they wanted to forget. Today, Germany’s attempt to grapple with Nazism, instilling an ethos of remembrance rather than evasion, is a standard-bearer worldwide for how nations can confront historical evil and systemic oppression. Making German schoolchildren visit a concentration camp or Holocaust museum hasn’t inoculated the country against extremism. But it has helped build, from tyranny’s ashes, one of our most resilient democracies; and ensures that Germany’s culture and politics remain ardently informed by its past.

Guilt, responsibility and atonement sit less well in other countries. The United States and Britain, fortified by myths of a “shining city on a hill” and a “new Jerusalem”, still fall well short of Germany’s accounting and memorialisation. But the legacies of slavery and empire are being pushed to the fore by younger Americans and Britons. Australia has apologised for its Stolen Generations — the thousands of Aborigines forcibly taken from their families under similar assimilation policies as Canada — but there is much unfinished business. As for Japan’s whitewashing of its imperial crimes, or Italy’s playful attitude towards its fascist past, no reckoning is in sight.

For the more than 40 countries that have held truth commissions since the end of the Cold War, results have been mixed. Some, like South Africa’s, have helped countries move forward despite their limitations; others have only pretended to address past injustices and abuses to legitimise a new political order.

Sinclair said in 2020 that Canada’s TRC “could have been done better” but “we now have a population of people in Canada who are actively talking about reconciliation and are openly supporting it.” A year later, spontaneous vigils and ceremonies are being held across the country. Memorials have sprouted up in Kamloops and seemingly every Canadian city and town. Masses of children’s shoes and Teddy bears have been laid out over fields, monuments, and on the steps of churches and federal buildings, where flags flew at half-mast. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who regularly speaks of the need to recast Ottawa’s relationship with Indigenous People, said Kamloops was “a painful reminder of that dark and shameful chapter of our country’s history”.

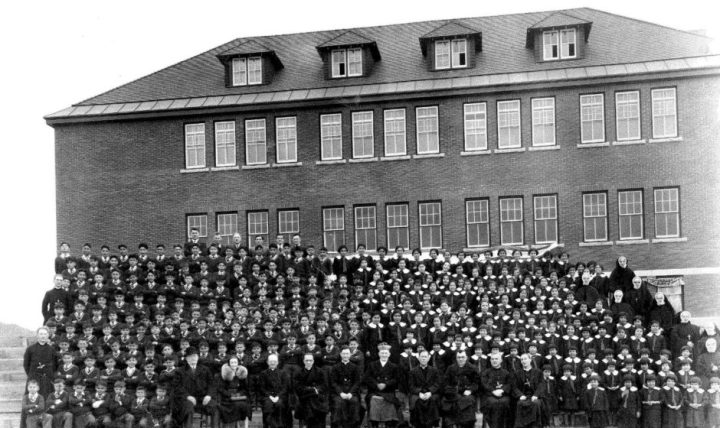

A photo from 1931, taken at the Kamloops residential school. (Photo: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

Trudeau is good at public rites of penitence, even if references to our “dark chapter” sound increasingly tawdry given the sluggish progress on the TRC’s 94 calls to action. He is also right to rebuke Canada’s collaborator-in-genocide, the Catholic Church, for doing less than required — including withholding school records and not formally apologising — for reconciliation. Since 2017 Trudeau has pleaded with Pope Francis to say sorry. The Vatican’s culture of secrecy and fears of mass litigation make him unlikely to oblige. Expect more weighty expressions of regret when other missing children are found. But no apology.

I hope I am wrong. This is not a moment for spin. The Vatican would be risking a lot if it acknowledged the church’s role in systematic oppression and potentially crimes against humanity. But historical shifts demand grand symbolic acts. Unless the church accepts that truth is more important than consequence, wounds will fester.

An undated photo of a classroom at Kamloops residential school. (Photo: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

***

Yet even grand gestures are not enough for reconciliation. Deep civic engagement and introspection are needed. As everywhere, no one wants to peer into wretched corners of their past. For most Canadians, bathed in the nice stories we tell ourselves, which are affirmed by a (mostly) admiring world, this is hard. Perhaps especially for teachers. Canada is a nation of teachers. Paid well, they command broad respect and share a strong commitment to an equal chance for all. Learning that vulnerable students were “disappeared” under their noses has been shattering.

For the nearly 40% of Canadians who are first- or second-generation immigrants, at least some distance can be put between their histories and the discovery in Kamloops. But for those of us fiftysomethings whose parents, and their parents before them, were born in Canada, a lot of questions have arisen in the past few weeks.

My first memory of learning about “Indians” in our hometown is coloured by envy. I loved to go fishing with my dad. But there were lakes and rivers around Kamloops that we didn’t have permission to fish in. Only “Indians” could. They had special rights; it was their land. And it wasn’t just fishing. They got free education, right through university, we were told. There were other entitlements, too. I remember thinking that there must be a good reason that this tiny minority of our town was favoured.

The history that we were taught in schools confirmed why. The vast expanse now called Canada was inhabited by myriad Indigenous tribes, some of whom were wiped out by European colonists, others stripped of their lands through treaties to make way for Canada’s westward expansion. Eventually, we learned, Ottawa made amends for conquest. The result was a raft of new laws, or enforcement of older ones, securing various cultural, political and land rights for peoples we were no longer supposed to call Indians.

Rights did not translate into better lives, however. Their situation remained desperate. Poverty, poor health and violence against women were rife. In Kamloops, the drunk and homeless sleeping rough in the town centre were mostly First Nations. At least that’s how I remember them. They looked pitiful; lifetimes of hurt were etched on their mottled faces. But it never occurred to my young self to ask why pain ran so deep in their communities. The few First Nations people that I knew personally were high achievers. Their success probably concealed the bigger picture in my mind.

In high school, one of my close friends was of Ojibway descent. I can’t recall her being second best at anything. She would graduate top of her class in medical school and become the first female General Surgeon of First Nations descent in Canada. Our local parliamentarian, Len Marchand, was a family friend. He was both the first “status Indian” to serve in Canada’s parliament and the first to sit in cabinet, as a minister in several posts under Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Justin’s father, in the 1970s. A member of the Okanagan Indian Band, he would later become a senator.

As a teenager, Marchand attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School for one year, in 1949. In his memoir, he writes glowingly of the Catholic sisters and brothers “who meant well by us, they genuinely cared about us”. He makes clear that he suffered no abuse at the school. One wonders what generations of Indigenous students might have achieved if Marchand’s experience was the norm. Evidence presented at the TRC suggests that it was not.

Education was the main source of my obliviousness. The history of Canada’s residential schools was not part of our curriculum. Selective remembering or wilful forgetting? Likely something more banal: no one thought it was very important. The numbers were small enough to omit from the uplifting sweep of a nation’s progress.

As happened in Germany, curricula in Canada have been injected with some painful truths. Atrocities committed against Indigenous People are now woven into the nation-building narrative taught in schools, rather than kept separate as a footnote. Survivors are now sharing their experiences with students.

Outside the classroom, pathways to reconciliation are thornier. Few if any countries have been as earnest and assiduous as Canada in trying to show their best selves to the world. Most Canadians still bristle at the idea that words like “genocide” and “colonialism” might apply to their country. It will take decades for such language to rest unopposed within the nation’s identity. If it ever does.

The lesson from Germany is to not be afraid. Canada need not be defined by the way it treated its Indigenous People. A dark chapter is not a whole story. As German writer Géraldine Schwarz observes of her own country, nations are strengthened in facing up to the ugliest periods in their histories:

“Keeping memory alive is not a moral accessory to look good. It helps us, together, to shape the future. It guides us to understand the world instead of suffer it, to avoid mistakes, to identify dangers — those that come from others but, above all, those that come from ourselves. It helps us to live more consciously.”

***

“Don’t get out of line, because there’s a graveyard and there’s also the river,” recounted one survivor to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation recently. This was the warning she received as a newly arrived six-year-old at the residential school in Kamloops.

The river she is referring to is the south branch of the Thompson River, which runs maybe 50m from the school’s front doors. Plenty of old photographs of the school have emerged since the discovery of the students’ unmarked graves last month. They include photos taken in the early 1900s up to just before the school closed roughly 50 years ago. In many, the school’s priests, nuns and students of the time are posing in rows at the front of the building. In none of the images that I’ve seen is the river visible. But brooding in the background of some photos are Kamloops’s sparsely forested mountain peaks, named Peter and Paul. It could be a scene from my own childhood. The lower parts of Mt Peter and Mt Paul are now speckled with houses, including my parents’, and a golf course. Otherwise, little has changed. Some trees on the mountains have been lost to fires over the years. But most of the trees have survived. Dotted around gullies and cliff edges, they seem frozen in time. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Welcome to civilisation and to planet Earth where homo sapiens are doing the most horrible things to each other and where most pretend this type of human behaviour was something far removed from the modern era.

No-one wants to admit that we are a murderous species, but that’s why we are on top of the food chain. And for in case you wondered, this type of behaviour stretches accross race, gender and religion.

Sad, very sad. Why have colonists, throughout history, acted in such a cruel and brutal manner to the people and nations they conquered? Why the hatred? Why the need to annihilate others completely? the vanquished are always regarded as non-citizens. Yet they were the original inhabitants. Even in this moving article the is the distinction between Canadians and First nation people. Canadians obviously referring to white settlers (Europeans and British). How tragic that even in 2021 we cannot make the mind shift and live in harmony with all people. Just like the faith, they all apparently follow, taught them. Why are they not more Christian in their actions and thoughts?

Why do colonists in a new country, feel we have the right to commit genocide against the original people. Kamloops Indian Reservation School in western Canada was part of a cultural genocide committed against Canada’s Indigenous People. Ref. “Dm 2021-06-14-when genocide hits home…”

In South Africa – the white and black colonists committed cultural genocide against the Khoi Khoi and the Khoi San as reported by many SA history books. The San were particularly hard hit because their vast hunting lands were desirable for farms. When the San resisted they were hunted down like vermin and were murdered. Pre-history indicates that the San were the original occupants of South Africa and the first people in Africa, possibly the mysterious primeval people in the “Out of Africa theory”, who then went on to populate the world.

Personally I have a deep fascination for the San – their harsh life-style, there mysterious language which appears to be like no other language – not even the Khoi Khoi click language is similar. I have read most literature with regard to the San. I even have a copy of Bleek & Lloyd’s Specimens of Bushmans Folklore 1911, collected from San incarcerated in Cape Town. presented with English on one page and llKung San Language on the other facing page. A Wonderful piece of work.

How could we have murdered these very special people – a priceless remanent of a community of wonderful beings who who have lived here for hundreds of thousands of years.