REFLEXIONS: READING IN THE PRESENT TENSE

Finding one’s place in the present

Locked down, locked in, many of us have had time to read more books than ever before. Readers, passionate about their own favourite books, are curious to know what writers have been reading during this bleak and lonely period. What was already on their shelves, what did they borrow, buy or read online?

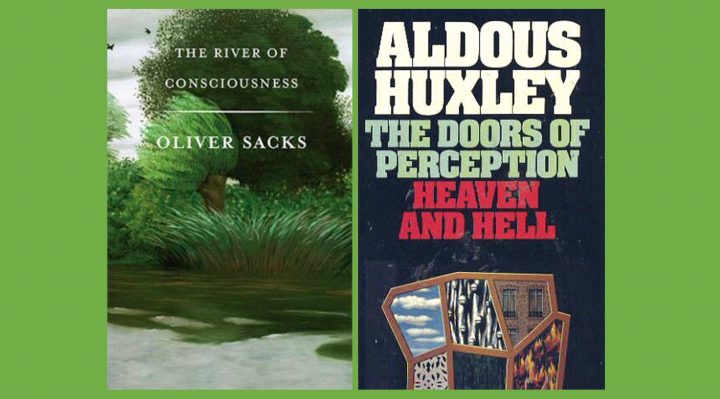

In this, the second series of Reflexions: Reading in the Present Tense, Ingrid de Kok and Mark Heywood continue to invite established and younger writers and other creative artists to reflect on a text that moved them, intellectually engaged them, frightened them or made them laugh. Our reviewer today is Rehana Rossouw who reflects on The River of Consciousness by Oliver Sacks and The Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley.

***

A breakdown followed by a lockdown sounds drastic, but it wasn’t. The government-mandated response to the pandemic was a welcome respite from a world gone coup-coup crazy. From the safety of our couch, my partner and I laughed at Donald Trump, gasped at footage of fires devouring huge forests and gawped at the soaring Covid-19 numbers.

Just slightly ahead of the curve on climate change and zoonotic viruses, we retreated a year before lockdown from the foul Johannesburg petri-dish to a village on the Garden Route. Our smallholding borders a game reserve stocked with the big five and other magnificent animals. There are sheep on the property to the right of us, a herd of goats to the left. The Outeniqua Mountains loom above, there’s a triangular slice of the sea below.

We aim to grow most of the food we eat, and a fat surplus for the needy in our new community. That will require the use of about a fifth of our land. The rest will be left largely as it is, covered by dune strandveld, a tiny and endangered biome in the fynbos kingdom. After we joined the ranks of the 2% of South African landowners who are female, the first task was to rescue the fynbos that lay buried under invasive wattle, pine and thorny hakea trees.

Our horticulturalist, Marcia Visser, and her energetic team set to work last September, when the first lockdown ended. She wielded her shrieking chainsaw like a sword, ululating with delight each time a mature tree came thudding to the ground. Trunks and thick branches were placed along the edges of the kloof to create berms that arrest the rain runoff and direct it to the centre, where a grove of about 100 wattle trees dominated the sky and the loamy soil below.

A blackened dead tree, its girth about four times larger than Trump’s, stood cradled in the branches of younger wattles that encircled it. Apparently it was the mother tree; she had nourished her youngsters, shared with them her knowledge of the environment and warned them about threats. Visser recommended books about tree communities, communication and neurology. She has huge empathy for trees, but felled every wattle surrounding the dead mother, which she left on the ground to rot.

The alien tree clearance was one of two major lockdown projects. The other was shaking the tendrils of a breakdown that clung to my muscles in tight spasms. Four days after we came to live on the Garden Route, I joined a yoga group that meets on the banks of an estuary dotted with flamingos and kingfishers. It helped me regain control of my breathing and banished the shallow panting that had been my oxygen intake for years.

The outstanding team of doctors who diagnosed me with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and treated the symptoms of my breakdown were all in hearty agreement that the cure was a piece of land where I could create a new basket of wholesome memories. One of the doctors suggested Oliver Sacks’s collection of essays, The River of Consciousness, a book I had once read and was on my shelf. It again provided the reassurance that severe mental injuries can be understood and cured.

The first essay in the book, titled “Darwin and the Meaning of Flowers”, affirmed my decision to purchase rural land as an antidote to my stressed life. Sacks examines Charles Darwin’s career as a botanist, an intellectual pursuit that outstripped his more famous adventures in biology and geology, and which provided hard evidence for his theories of evolution. Sacks describes one of his many experiments seeking to prove that the roots of plants acted like sense organs that directed growth and movement: Darwin lay face down on his lawn, painstakingly transferring pollen on flowers that differentiated from each other.

Flowers, Darwin said after years of careful study, were “wholly intelligible as products of accident and selection, of tiny incremental changes extending over hundreds of millions of years”. All living things were descended from a common ancestor, he declared, and all are related to each other.

More than two centuries after Darwin’s observations were published, scientists have established that plants and animals share 70% of their DNA. They confirmed that plants appeared on Earth nearly 100 million years ago and forged symbiotic relationships that directed the development of all other species on the planet.

Sacks concludes that this knowledge of his biological antiquity traced to the beginning of life on Earth, his biological uniqueness as a result of variation and his biological kinship with all life “roots me, allows me to feel at home in the natural world, to feel that I have my own sense of biological meaning, whatever my role in the cultural, human world”.

Another essay in The Rivers of Consciousness, “The Fallibility of Memory”, warns that recovered memories of experiences so traumatic that they are defensively repressed can be implanted in people with PTSD. Events are not directly transmitted or recorded in our brains, Sacks explains, but are experienced and constructed in a highly subjective way and reinterpreted or re-experienced when they are recollected. “The only truth is the narrative truth, the stories we tell each other and ourselves – the stories we continually recategorise and refine. The wonder is that aberrations of a gross sort are relatively rare and that for the most part our memories are solid and reliable.”

All memories are constructed by “what we read, what we are told, what others say and think and write, as intensely and richly as if they were primary experiences”, Sacks continues. “It allows us to see and hear with other eyes and ears, to enter into other minds, to assimilate the art and science and religion of the whole culture, to enter into and contribute to the common mind, the general commonwealth of knowledge.”

Another member of my medical team suggested that I research the benefits of psychedelics in the treatment of PTSD and anxiety. This led me to another book on my shelf, its slim pages read frequently over the decades: Aldous Huxley’s twin essays The Doors of Perception, and Heaven and Hell. In them he argues that mescaline and lysergic acid are drugs of unique distinction that should be exploited for the “supernaturally brilliant” visionary experiences they offered users, and as cures for mental illnesses.

Administered in suitable doses, Huxley claims, mescaline profoundly changes “the quality of consciousness”, yet is less toxic than most other substances used to treat mental problems. After taking mescaline, Huxley describes the experience of travelling inside his mind to a “perpetual present made up of one continually changing apocalypse”.

He communed for hours with a vase of flowers in which he discovered “the divine source of all existence”. His eyes locked on three flowers “shining with their own inner life and all but quivering under the pressure of the significance with which they were charged”. Huxley concludes that mescaline “lowers the efficiency of the brain as an instrument for focusing the mind on the problems of life”.

US pharmacologists and psychologists began experimenting with mescaline in the 1950s, but their early breakthroughs were suppressed by successive government wars on drugs. The Guardian reported in May 2021 that ketamine, psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms) and MMDA had been approved for use in the UK and the US as treatments for complex PTSD and depression. In 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration awarded therapy status to psilocybin as a treatment for treatment-resistant depression. In December 2019 a ketamine-like drug – esketamine – was licensed for use in the UK as a treatment for major depression. “It starts working in hours, compared with weeks or months with traditional antidepressants,” The Guardian reported. Brain scans show that substances like LSD weaken the influence of prior beliefs that the brain uses to make sense of the world. Research trials on the impact of psilocybin, combined with therapy, resulted in marked reductions in patients’ depressive symptoms within weeks of use.

Medical professionals in South Africa are also mobilising for the use of psychedelic drugs in therapy, the radio station Cape Talk reported in October 2020. They have launched the Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy Initiative of South Africa and expect government approval for psychedelic treatment within three years.

The Garden Route has several eccentric communities: the deluded ivermectin fanatics, the CBD cure-all crowd who treat their pets with the products too, the gone-with-the-fairies living in the dense forest. Finding magic mushrooms wasn’t hard at all. Our purchase coincided with the release of Fantastic Fungi, a documentary that sets out to show how mushrooms can save the world with their networking abilities. The film’s footage of growth and decay is spectacular, as is its depiction of mycelium, a network of kilometres-long branching fungal colonies that play a vital role in the decomposition of plant material. Their fruiting bodies live above ground – the profusion of mushrooms found in nutrient-rich soil.

Mycelium operates as an underground internet, linking the roots of different plants. By tapping into the fungal network, trees and plants assist their neighbours by sharing nutrients and information – and sabotage unwelcome pests and plants by spreading toxic chemicals. I wanted to tap into this community, using magic mushrooms as a conduit.

My experiment was doomed to failure. Impatient for results, I swallowed far more mushrooms than Huxley and other experts prescribed. Instead of communing with me, the plants and trees on my land rushed up to my face in a fantasia orgy of swirling colours. It was overwhelming so I retreated and eventually finally found comfort curled under a blanket. With eyes tightly shut I watched as the infinite space behind my eyelids flamed burnt orange, I followed black tendrils swimming and dancing in its fire. Could they have been mycelium threads?

After four months, at the end of the second lockdown, Visser and her team had cleared our land of alien invaders. They fed a chipper for days with the remnants of the trees they had hacked out. The chipped detritus was returned to the land to create new topsoil. Within weeks the spectacular results of their work emerged, hidden in the dense shade of the remaining indigenous trees. First to arrive were flat-topped mushrooms that travelled along the trunks of felled pine trees, their fiery orange hues matching the landscape behind my eyes when I disappeared into a fungal psychedelic fantasia. Toadstools came next, growing in shy clumps in the deep shade. Long white tendrils appeared in the leaf mulch left behind by the wattle grove and gobbled it all.

Visser planted our first batch of replacement trees, yellowwoods, silver trees and keurboom. The indigenous Cape beech and camphor trees that had led misshapen lives under the canopy of aliens reared up in the summer sunshine to claim their space and sprouted younglings in their shade. Insects and golden orb spiders took up residence and birds came to feast on the wild peaches.

Walking on my land now I often find myself lost in reverie. But unlike past moments of forgotten time, I am no longer ripped from the present to dwell in the trauma of the past. A clump of mushrooms, the flutter of butterfly wings and the shimmering chests of sugarbirds transfix me and drag me into a wonderful present, into an environment that is teaching me how to recover and live in harmony with all other life forms. There is no need for psychedelic enhancement. I have come home to the shelter of my biological roots where my eyes are fixed on a riot of colours that signal the true meaning of life. DM/MC

Rehana Rossouw, a journalist for three decades, has a master’s degree in creative writing from Wits University. Her first novel, What Will People Say?, won the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS) prize for fiction in 2017. Her second novel, New Times, was longlisted for the Sunday Times Literary Awards in 2018. Her first work of nonfiction, Predator Politics, was published in 2020.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.