YOUTH DAY

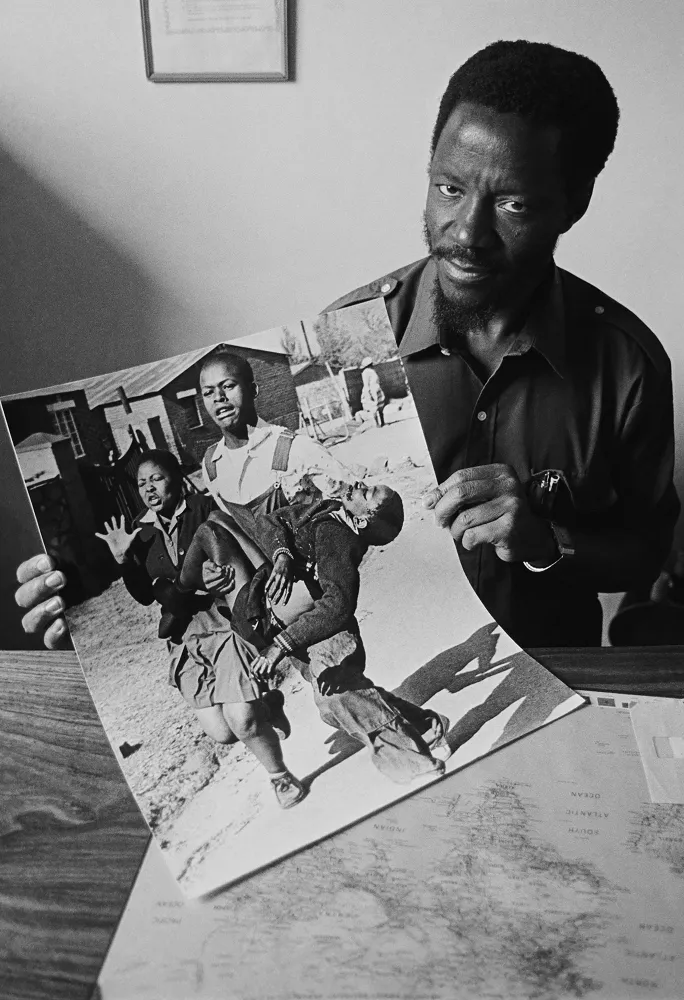

Hector Pieterson and the 16 June photograph that changed everything

Photographer Sam Nzima was in Soweto on 16 June 1976, when police opened fire on schoolchildren protesting against Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. His photographs from that day – including the iconic image of Hector Pieterson – were published around the world. Although his work helped open up opportunities for other black photojournalists, Nzima left the profession as a wary and bitter man.

The first photograph captured their innocence – a sea of smiling faces – as the schoolchildren began their march.

Photographer Sam Nzima had stepped away from the crowd, on to the side of the road, to shoot the black-and-white picture. It was possibly one of the first he took on a morning that would change everything forever. By the end of that day, he would be famous – and a marked man.

Nzima is known for taking the iconic photograph of the mortally wounded Hector Pieterson on 16 June 1976, but his other images, which are seldom seen, provide context to that fatal day and tell more about the man he was.

Nzima’s day had begun early.

The World newspaper had been tipped off that there would be a mass march of schoolchildren in Soweto to protest the compulsory introduction of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in schools.

Together with reporter Sophie Tema, Nzima headed out and met pupils at the Naledi High School in Soweto at 6am. He watched as the children wrote out the placards they planned to carry.

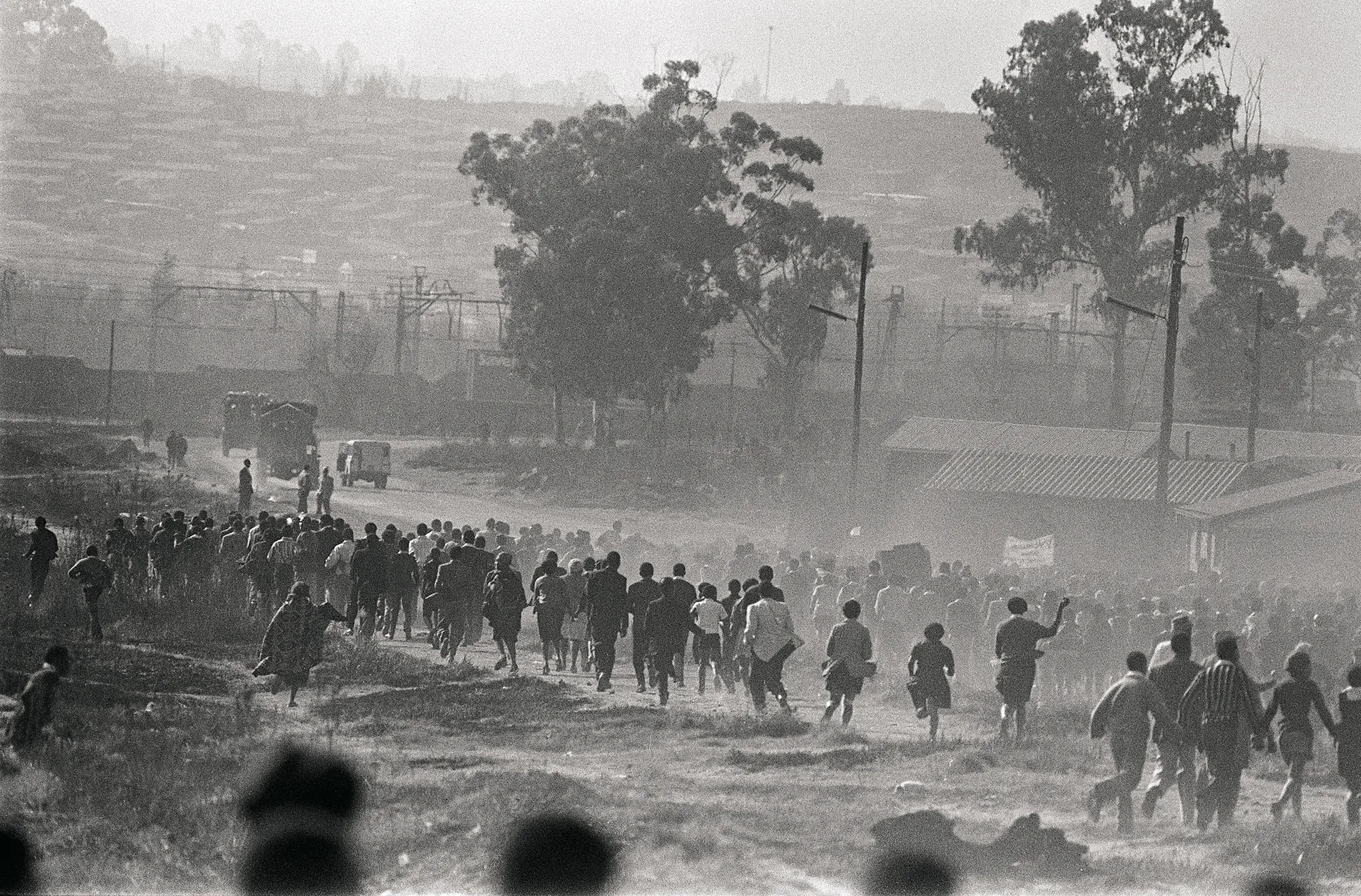

As the sun climbed higher in the winter sky, the students began to move. The plan was to head to Orlando Stadium, where they would air their grievances. As they marched, children from other schools joined.

At the Morris Isaacson High School, student leader Tsietsi Mashinini climbed a tree so he could be seen, and stressed to the 15,000-strong crowd that they should remain peaceful.

But, already, things were turning violent. Nzima’s Pentax camera turned to the skirmishes that were flaring. In one photograph, students, surrounded by swirls of tear gas, hold dustbin lids as shields as they throw stones at the police.

Then there is the photograph of the black police officer aiming his revolver at the students. Exactly when Nzima took these pictures on 16 June is unclear.

‘He’s not using a long lens’

Taking that image of the police officer was a brave act. And it is a photograph that James Oatway, who is of a new generation of photographers, finds particularly impressive. “To me, it is a very powerful picture because he’s close. He is not using a long lens; it is maybe a 50mm lens or less. And the cops are shooting, which makes it very unusual,” he says.

At Orlando High School, the children paused to wait for others to join the march. It was there that they heard the news that a big police convoy was on its way.

The students were told to disperse. Instead, they held their ground and sang Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, which Nzima would later say agitated the police commander who drew his pistol and fired. Then all hell broke loose as other police officers opened fire.

Students scattered as shots rang out; Nzima hid in a house.

The Young Lions wanted to stop Peter Magubane from photographing on the morning of 16 June 1976. Magubane explained to them: ‘A struggle without documentation is no struggle.’ They agreed and issued an instruction that photographers and journalists be allowed to document the march. (Photo: Peter Magubane)

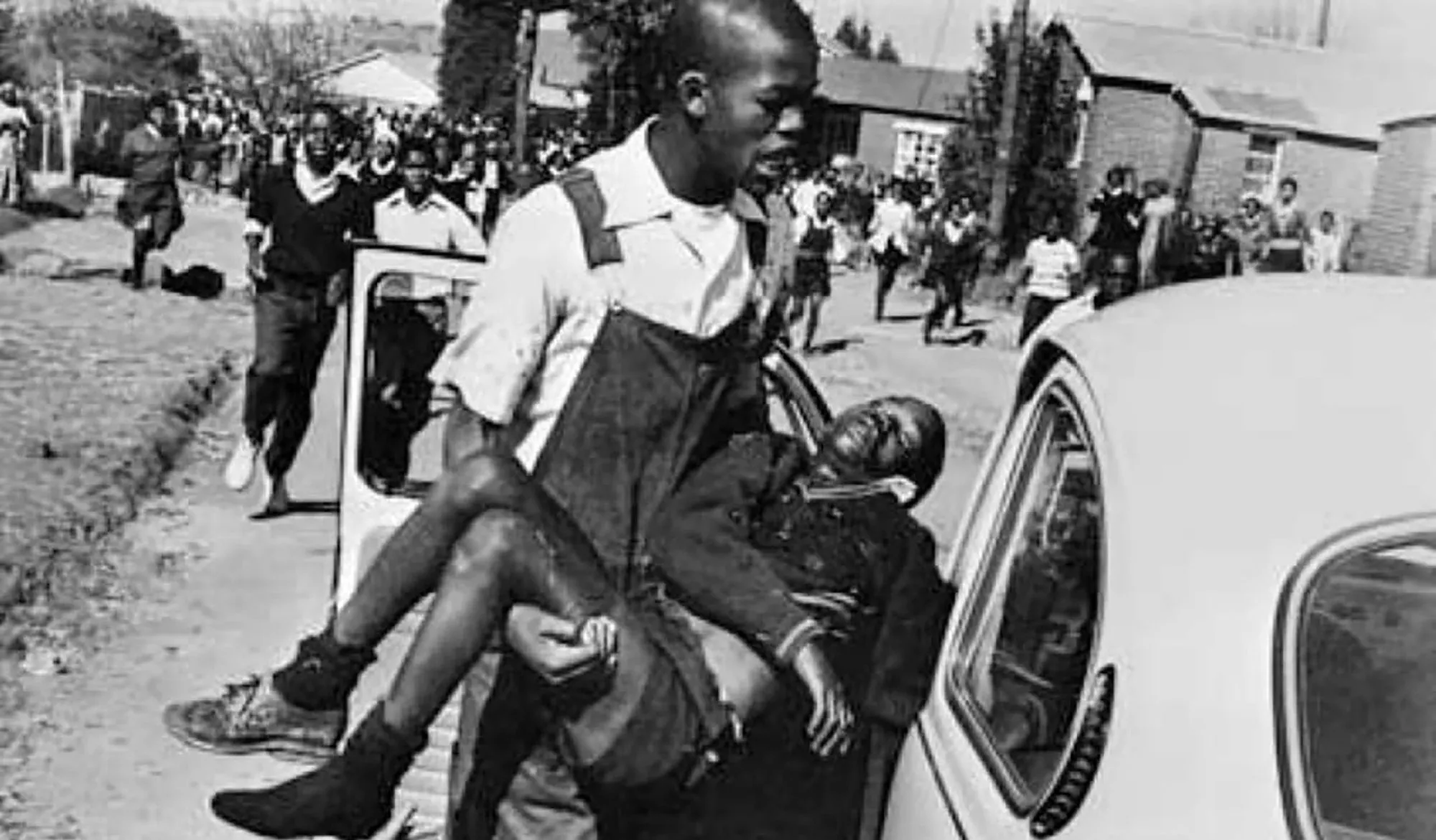

“I got out from the house. The police had ceased firing, and I saw a little child falling down. There comes this tall boy Mbuyisa [Makhubo] and picked him up. As Mbuyisa picked him up, I went with my camera,” Nzima would tell a reporter from Forbes magazine in 2014.

Nzima would later tell that, in those frenzied moments, he just took six frames of Hector Pieterson.

His first photographs were taken from a distance, as Nzima closed in on Makhubo, who had Pieterson in his arms. A wide-angled shot reveals the masses of children behind him, running up the street. Nzima would later say that police were still firing.

“Remember, his camera is manual focus, and he is shooting fast action. That is a serious talent,” says Oatway. “And his adrenaline would have been pumping.”

Nzima got in closer, stepped to the side of Makhubo, and, there, he got it – the photograph that would come to symbolise the struggle against apartheid.

Photo that went around the world

In the decades since the picture was taken, the image has been reproduced millions of times. The photograph has been scrutinised for symbolism; it has even been compared to the image of Mary carrying Jesus.

But the Hector Pieterson caught in Nzima’s lens in those moments was already dead or dying. A 12-year-old boy who, his sister Antoinette would tell the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) years later, had joined the march not out of political conviction, but out of curiosity.

The last picture Nzima took of Pieterson is of the boy being bundled into the VW Beetle Tema was driving. His eyes half-open, his school shoes flecked with blood. He was rushed to a nearby clinic, where he was declared dead.

Last breath of Hector Pieterson in the arms of Mbuyisa Makhubu in Soweto on 16 June 1976. (Photo: Sam Nzima)

Fearing that the police would confiscate his camera, Nzima hid the film in his sock and made his way back to the offices of The World. There, after much debate, editor Percy Gobozo decided they would run the Hector Pieterson picture on the front page.

From there, the photograph took on a life of its own, quickly appearing in newspapers around the world.

The others who were there

Photographer and historian Omar Badsha has researched which photographers were in Soweto that day. It appears that, besides Nzima, there were just two others – Peter Magubane and Alf Kumalo.

Peter Magubane was in Orlando West on 16 June. He would tell of his experiences that day at the TRC hearings in 1996.

Magubane spoke of having to talk down a crowd who had pulled a Western Board official from a van and had wanted to kill him.

Later, he found police officers standing around the body of Dr Melville Edelstein, one of two white people who were killed on 16 June.

From very early in the morning of 16 June 1976, school learners began to make their way to the various meeting points for a mass demonstration to protest against the use of Afrikaans in ‘black’ schools. (Photo: PLP / Alf Kumalo Family Trust)

“I photographed that and went to near Tshabalala garage in Jabavu. There, I found the body of a man [who had been] driving a truck that belonged to his employer. He was asked to hand the truck over. He refused and said, ‘I am working for my children.’ He was mercilessly killed and set alight.”

He continued: “Soweto was a different place altogether that day. Police were not able to come into the township after they had killed Hector Pieterson. They were kept at bay, out of the township.”

Photographer Kumalo was also covering the march that Nzima followed. After Pieterson was shot, the students turned on him and stole his camera. Another student was going to knife him when someone recognised him and told the crowd not to touch him.

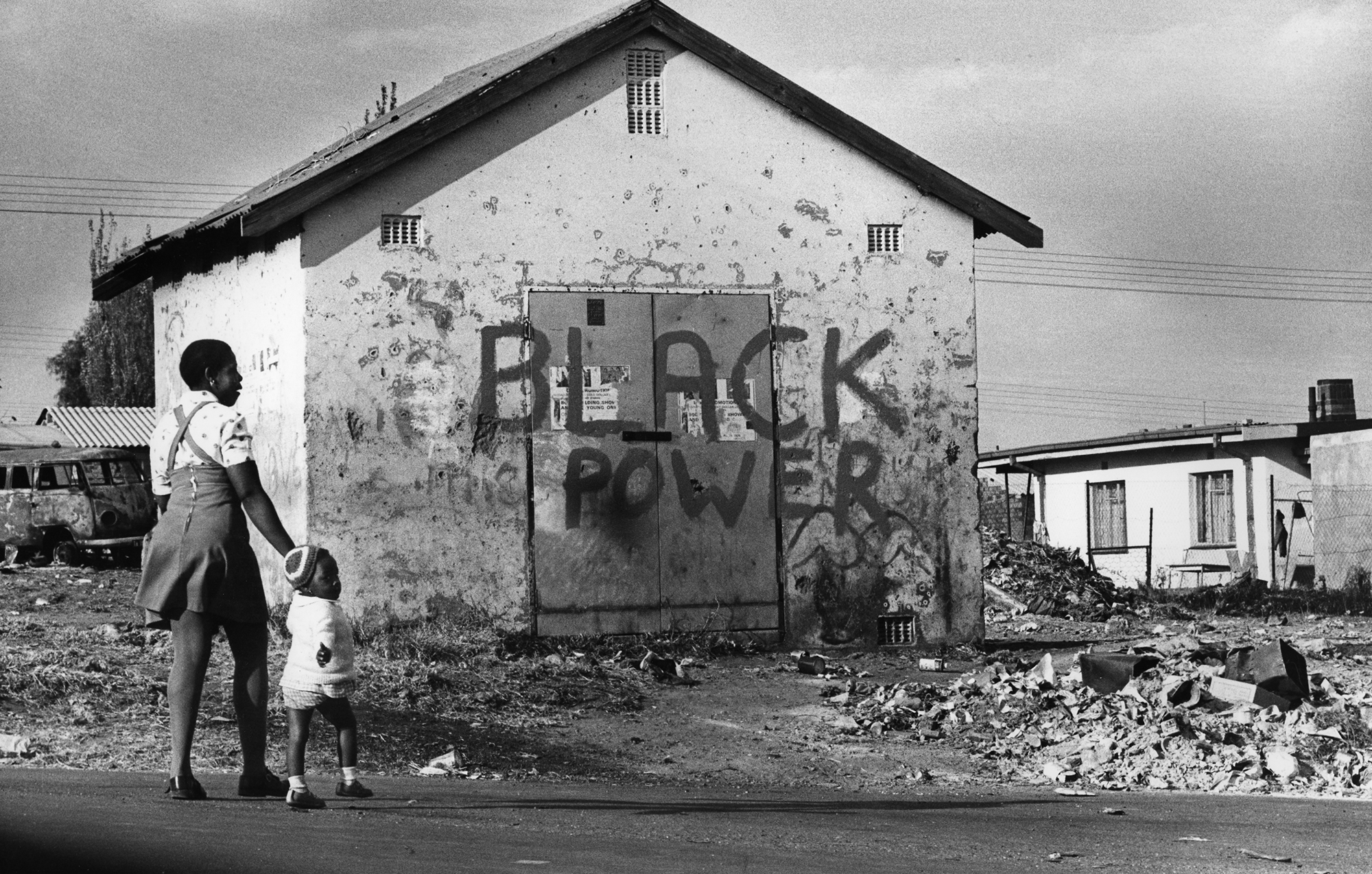

In the days and weeks that followed, Magubane and Kumalo would continue to photograph the uprising that spread from township to township, province to province.

But who wasn’t there was the man who had witnessed the spark of the uprising. Nzima had received death threats from the police and fled Johannesburg to his home town of Lilydale in Mpumalanga. There he stayed.

The three photographers in Soweto on 16 June 1976 would leave a legacy.

“June 16 opened the space for black photographers and journalists to find work in the mainstream and alternative press. This, because they couldn’t get white reporters and photographers in too many areas,” explains Badsha.

Those photographers would go on to photograph more of the atrocities of the apartheid state. And, as with Nzima’s photograph, they would appear overseas not only in newspapers but in travelling exhibitions that chronicled what was happening in South Africa’s townships.

But none of those images would have the impact and endurance of the Hector Pieterson photograph. Over the years, it has appeared on posters, it has been incorporated into artworks and stencilled on to T-shirts.

Late afternoon in Soweto on 16 June 1976. (Photo: Peter Magubane)

“The image reflects a lot of different things – the good, the bad, the meaningful and the flippant. And what it speaks to is the power of the image,” explains Professor Ruth Simbao of Rhodes University’s fine art department.

Preserving the legacy

Of the three photographers on the ground on 16 June, only one is still alive – Magubane is 89 years old. The task now is preserving their legacy.

The Soweto uprisings may still be in living memory, but Badsha points out that there is still much to be researched and learnt about the time. Photographic archives are being gathered and digitalised.

Photographer and archivist Paul Weinberg heads the Photographic Legacy Project, which is gathering and storing Kumalo’s collection.

It was said that Kumalo kept the majority of his archive in the boot of his car. “Let’s put it this way, Alf didn’t have a good system,” says Weinberg.

Kumalo and Magubane went on to write books and were fêted around the world, but Nzima became bitter. He saw his image being used over and over and, because he didn’t have copyright, he didn’t see any of the money the photograph was generating. When he appeared at the TRC in 1996, Nzima was asked if he would return to photography. “No, I don’t want to,” he said.

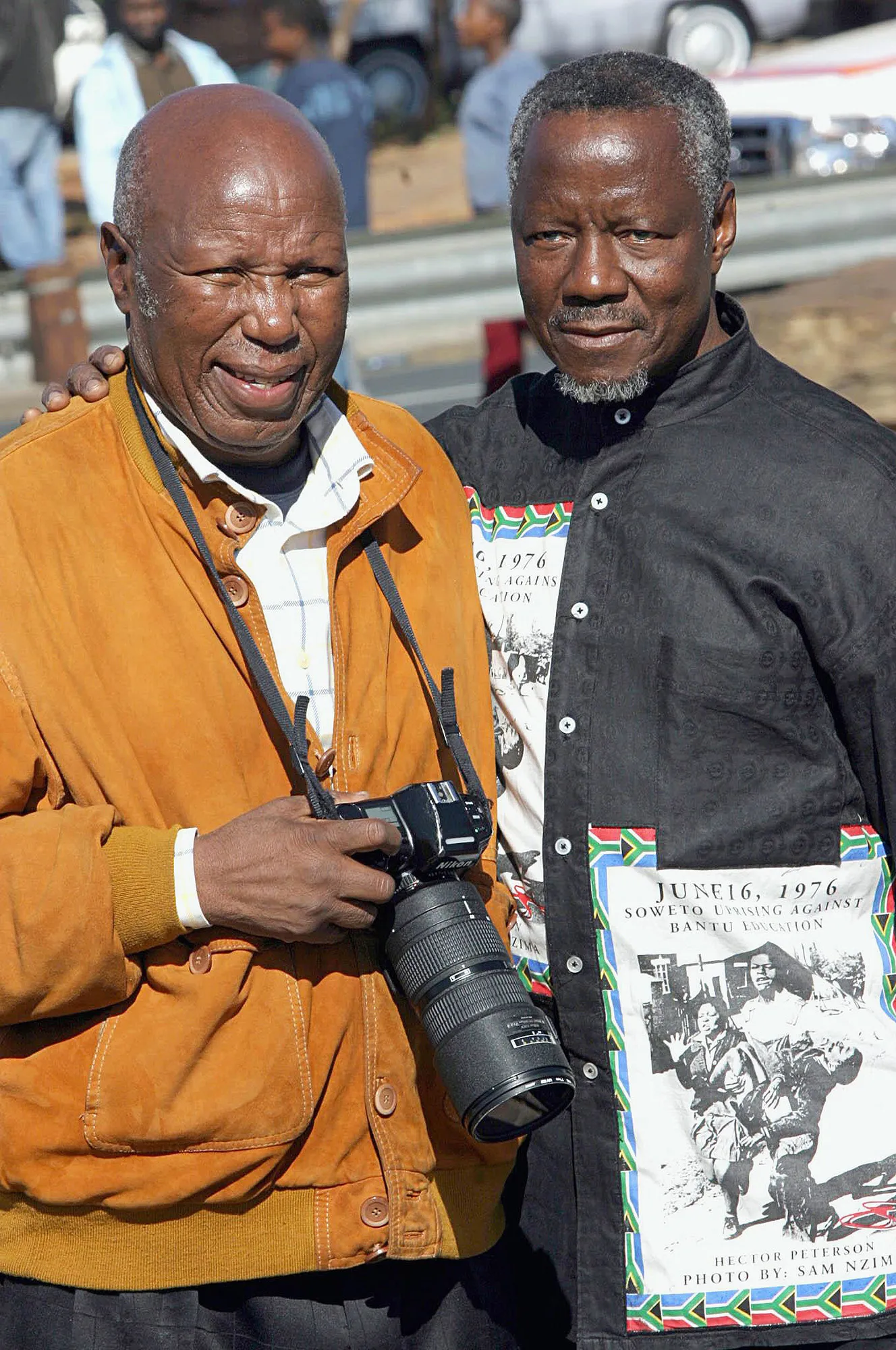

Veteran South African photographers Alf Kumalo and Sam Nzima, both photographers of the Soweto uprisings of 1976, celebrate Youth Day on 16 June 2005. Nzima’s photograph of Hector Pieterson is printed on his shirt.

Nzima would finally get the copyright for this photograph – thanks to a conversation, overheard by chance, in The Star newspaper’s syndication department.

“I heard one of the women who worked there talking about selling Sam’s picture and selling it for a ridiculously low price,” says Robin Comley, who at the time was photographic editor at The Star.

With the help of The Star’s editor at the time, Peter Sullivan, they began working to get Nzima ownership of his picture.

“We did get copyright for Sam,” recalls Comley. “And then I had the very, very pleasant task of phoning him one day and telling him: ‘Guess what?’ This picture is now yours again. And he was speechless, as I recall, for a while.”

A new generation

Since then, a new generation of photojournalists has taken over from what Nzima, Magubane and Kumalo started.

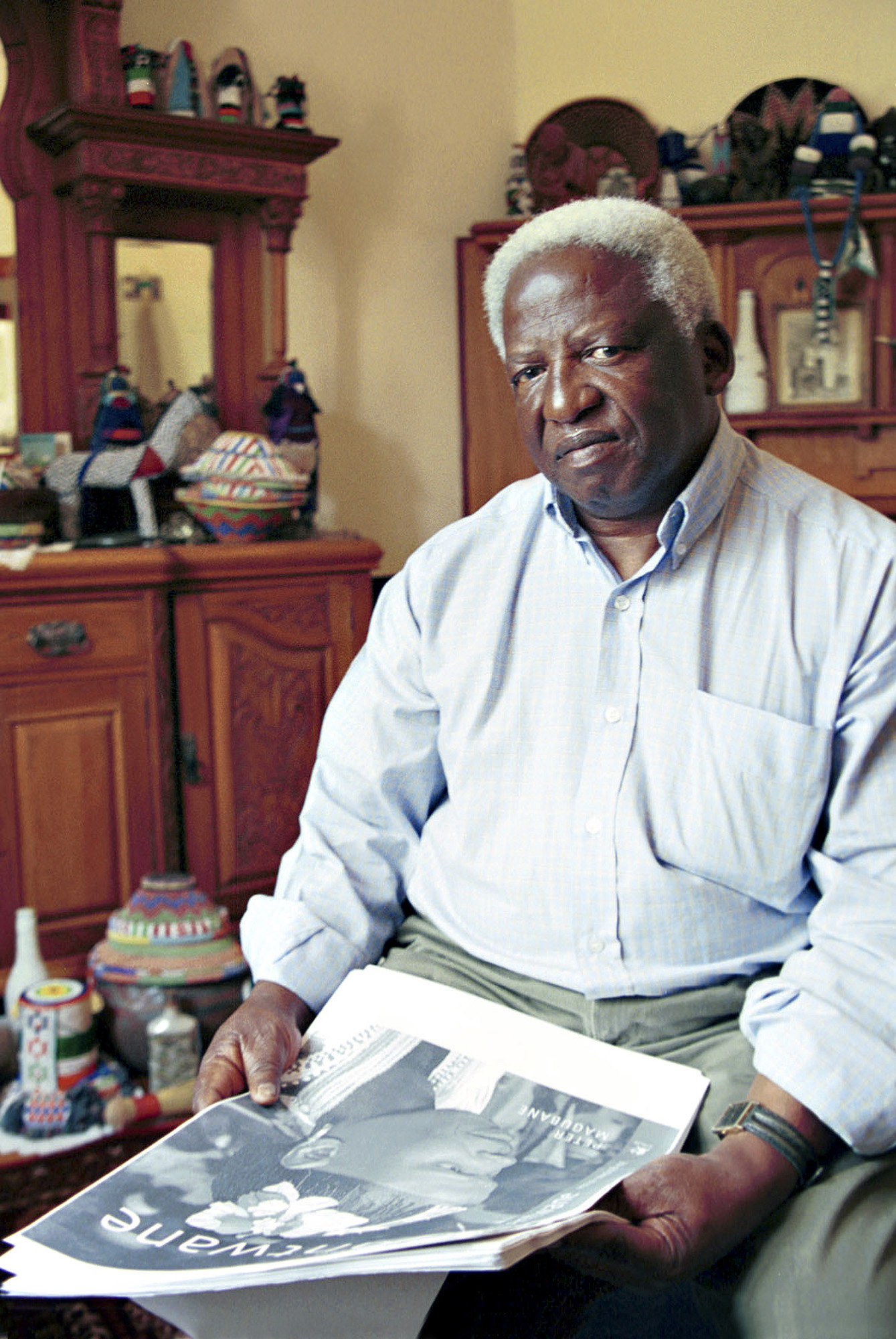

Well-known South African photojournalist and photographer Peter Magubane on 19 October 2000.

The march of technology – in the form of digital cameras – has made getting that picture easier. But with democracy came new challenges. There are still the bloody protests, but the focus of many of them has turned to foreigners who are seen as criminals and people who steal jobs from locals.

It was during a bout of xenophobic unrest that Oatway, like Nzima 39 years earlier, would take an iconic photograph of a mortally wounded man.

In Alexandra in Johannesburg, Oatway photographed the beating and stabbing of Emmanuel Sithole, a Mozambican trader. The incident took just 27 seconds.

After the photograph was published, Oatway was accused of not helping Sithole.

Many didn’t know that Oatway, like Nzima, put down his camera and tried desperately to save Sithole.

Oatway, together with reporter Beauregard Tromp, bundled Sithole into a Sunday Times staff car and rushed to get him help.

They were eventually directed to Edenvale Hospital, where Sithole died shortly afterwards.

Not long after Oatway’s photographs appeared in print, he received a message from a journalist in Mbombela. The journalist told him that Nzima had seen the pictures and wanted to congratulate Oatway and tell him he had done an important job.

The former photojournalist who had forsaken photography had recognised a good image and its importance to South Africa and the world.

“And that really meant a lot to me, because I believe that photograph he took is one of the most important single images that has been captured in South Africa,” says Oatway. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

An outstanding article, deeply sad.