REFLEXIONS: READING IN THE PRESENT TENSE

Sol Plaatje under lockdown

Locked down, locked in, many of us have had time to read more books than ever before. Readers, passionate about their own favourite books, are curious to know what writers have been reading during this bleak and lonely period. What was already on their shelves, what did they borrow, buy or read online?

In this, the second series of Reflexions: Reading in the Present Tense, Ingrid de Kok and Mark Heywood continue to invite established and younger writers and other creative artists to reflect on a text that moved them, intellectually engaged them, frightened them or made them laugh. Our reviewer today is Jane Taylor.

***

My mother’s children were angry with me; they made me the keeper of the vineyards; but mine own vineyard have I not kept.

– A fragment from Sol Plaatje’s epigraph to his Native Life in South Africa, 1916.

I have been re-reading several of the works by Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje (1876-1932). What variety and surprise: proverbs, meditations on legal interpretation, reflections on Shakespeare, land rights.

Plaatje published widely, ran a newspaper, assembled a valued collection of Sechuana Proverbs, translated Shakespeare into Setswana, wrote about sex across “the colour bar”, about labour exploitation, and was the first African to write a novel in English. He was the first secretary-general of the SANNC, and a campaigner in England and North America for land and political rights in the emerging South Africa.

If Plaatje is much known in his own country in 2021 it is as the author of Native Life in South Africa, an extensive documentation and analysis of the impact of the 1913 Natives Land Act. The fragment that Plaatje uses from Song of Songs, as the epigraph to his Native Life in South Africa, is at the head of my review here. It anticipates the intergenerational crisis that is one element of the legislation’s legacy.

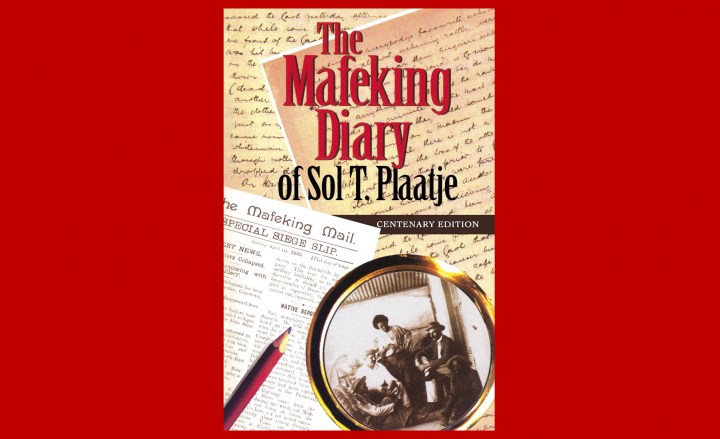

I have invoked Native Life in South Africa to prompt the reader of this review to imagine the breadth and range of Plaatje’s writings. My review, however, focuses on Plaatje’s lesser-known text – timely for our lives under lockdown – Mafeking Diary, a record of his experience of the siege of Mafikeng in 1899-1900. (The two spellings – Mafeking/Mafikeng – are evidence of the history of the place and they suggest something of the richness of linguistic heritage in the region. The colonial spelling was Mafeking – that is the version in the published edition that I have been reading.)

This Mafeking Diary is unique as the only surviving first-hand written account of the experience of the war from the point of view of an African. It suggests unpredictable insights into the current experience of the Covid-19 lockdown, through Plaatje’s observations on life and death under the siege.

Rather enigmatically, the first entry in the diary (Sunday 29th, 1899) appears to document the moment of Plaatje’s death from a Mauser bullet to the head. So uncanny is the description, that I quote the episode in full:

“After I left Mr Mahlelebe yesterday I came through the jail yard onto the Railway Reserve’s fence as Mauser bullets were just like hail on the main road to our village. I had just left the fence when one flew close to my cap with a ‘ping’ – giving me such a fright as caused me to sit down on the footpath. Someone behind me exclaimed that I was nearly killed and I looked round to see who my sympathizer was. When I did so another screeched through his legs with a ‘whiz-z-z-z’ and dropped between the two of us. I continued my journey in company with this man, during which I heard a screech and a tap behind my ear: it was a Mauser bullet and as there can be no question about a fellow’s death when it enters his brain through the lobe, I knew at the moment that I had been transmitted from this temporary life on to eternity. I imagined I held the nickel bullet in my hand. That was merely the faculty of the soul recognizing (in an ordinary post-mortal dream) what had occasioned its departure – for I was dead! Dead, to rise no more. A few seconds elapsed after which I found myself scanning the bullet between my finger and thumb. It was but – a horsefly.”

This is evidence of a deft and wry story-teller. We are gulled into the diarist’s presentist and delusional thinking. Plaatje is inside the event, and so are we. He does not unfold his narrative from the reassuring temporality of full knowledge and recollection. Rather we live with him in the immediacy of that tap behind his ear. The “realisation” of his death plays in his mind, as a recurring trauma.

With such episodes, Plaatje reveals to us the structure of haunting persistence.

“Our ears cannot stand anything like the bang of a door: the rat-tat of some stones nearby shakes us inwardly. All of these things have assumed the attitude of death-dealing instruments and they almost invariably resemble Mausers or Dutch cannon.”

He is living in a world destabilised – such as we might recognise in a post-Covid experience. Common-sense wisdom urges us “not to take things for granted”; but the turmoil that has been visited upon the world since December 2019 suggests that life is not sustainable unless a fair proportion of daily existence is held precisely by that which is “taken for granted”.

As the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein intuited, our practice of daily life relies on what we might characterise as Certainty. (Wittgenstein had himself fought in World War 1, on the Eastern Front.) Plaatje’s diary, by contrast, shows us the human capacity for survival in extreme crisis.

What a melancholy gift:

“We have on this day received more shells than on any other occasion since the 25th ultimo. But we are gradually getting used to them and it is getting more like a holiday than a siege.”

There are unlikely celebrations of the everyday. On Friday, 17 November he notes:

“What a lovely morning after yesterday’s rains. It is really evil to disturb a beautiful morning like this with the rattling of Mausers and whizzes and explosions of shells.” Plaatje’s is no myopic vision – he is living in the presence of death, that is certain, and he notes many morbid horrors:

“I learnt that the first shell of this morning burst near one of the railway cottages and killed a young fellow by blowing off his belly and pitching his intestines onto the opposite roof. [I]f we are going to die at this rate I am sure there will only be wounded people hopping about single-armed and with amputated legs to tell the history of the siege.”

Plaatje observes that time itself is difficult to grasp. It “is very difficult to remember the days of the week in times of war”. He cites a friend who has mislaid time: “What, Sunday? He thought it was Thursday (Ha! Ha!)”

That sardonic inscription of laughter suggests a derision arising from the fact that one’s self clings to calendrical time only with difficulty outside of the habits of relation and sociality. These things we now understand as a result of the pandemic. There is testimony aplenty of how difficult it is under lockdown to recollect whether an event passed a week, a month or a year ago.

The diary is a profound document of a critical phase in the history of settler-colonialism in its particularity at the turn of the 20th century. Plaatje includes letters and notices from Colonel Baden-Powell, who was overseeing the British camp during the siege. He copies out in full Baden-Powell’s letter to General Snyman, the Boer commander, Plaatje revealing the rich complexity of his thinking about his historical moment. This is how he introduces that letter (8 December 1899):

“As a rule the ‘Native Question’ has, I believe, since the abolition of slavery, always been the gravest question of its day. The present siege has not been an exception to this rule for Natives have always figured pre-eminently in its chief correspondence.”

The Tshidi-Barolong, (of whom Plaatje was a self-identified member) aligned themselves with British interests. Some other Barolong, however, were fighting alongside the Boers. This complexity prompts us to hold in mind the contradictory contexts of imperial conquest.

Plaatje’s record also makes available some of Baden-Powell’s propaganda interventions.

The British colonel’s post to “the Burghers of the Z.A.R” (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) attempts to undermine Boer resistance by asserting that German, American and French interests are aligned with the British. Yet the logic of a British self-legitimating plunder is explicit in Baden-Powell’s argument: “France has large interests in the gold fields identical with those of England; and Italy is entirely in accord with us; and Russia sees no cause to interfere.”

John Comaroff, when a young anthropologist, came across the diary in an old scrapbook in the possession of Plaatje’s grandson. It is a document of extraordinary compassion, grieving for allies and enemies, as well as the suffering of animals. It provides a record of shocking misery, much of it the result of starvation: Plaatje notes “I long for food”. As supplies are diminished, norms and habits are shifted, and we are aware of the sadness in the writer’s observations:

“I saw horseflesh for the first time being used as human foodstuff. It looked like meat with nothing unusual about it,” that is, until he glimpses “their long ears and bold heads, and those were the things the people are to feed on. The recipients, however, were all very pleased to get these heads and they ate them nearly raw.”

Recent scholarship has examined the uneven ways in which food was distributed within the camp between British and the allied Barolong hostages of the siege. This is perhaps implicit in that indication of “the people” who are the recipients of the horse heads. Plaatje observes on Sunday, 13 January, when meat rations are reduced, that “there is a great difference between white and black even in a besieged town”.

The centenary edition has footnotes full of linguistic scholarship and historical richness. The notes also reveal Plaatje’s open-hearted and generous sensibility, even under conditions of siege. When a Boer spy is arrested by the British (see Tuesday, 16 January), Plaatje tries unsuccessfully to save the man’s life. The footnotes inform us that Charles Bell, Magistrate of Mafeking, comments “that all Plaatje had ‘inherited from those German missionaries was their absurd benignity and nothing more’.”

Now is the time to read Sol Plaatje’s The Mafeking Diary. DM/MC

Jane Taylor is a scholar with an interest in the history of diaries and confessional texts. She currently holds the Andrew W Mellon Chair in Aesthetic Theory and Material Performance at the Centre for Humanities Research at UWC, where she develops creative enquiries into the histories and futures of material culture. Taylor has two published novels (The Transplant Men and Of Wild Dogs – which won the Olive Schreiner Award), wrote Ubu and the Truth Commission, and the libretto for Confessions of Zeno. Recently she has been writing lecture-performances, bringing her scholarly and creative practices together.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.