MATTERS OF OBSESSION

Taxis and art: Rethinking ‘Cape Malay’ and ‘Coloured’ identity

Artist Thania Petersen has embarked on a project to bring art into minibus taxis. As a pilot for the project, she covered a taxi in artwork that interrogates the construction of ‘Cape Malay’ and ‘Coloured’ identity and proposes a way forward.

Since the beginning of May 2021, one particular minibus taxi that traverses the route between Hanover Park and the Cape Town city centre has been covered in artwork by Cape Town-based artist Thania Petersen. The 40-year-old artist’s work has been collected and exhibited widely, from the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town to the World Cultures Museum Rotterdam in the Netherlands to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC, through to Brazil’s Oscar Niemeyer Museum Curitiba, to name a few.

Self-portrait 1, from the artist Thania Petersen’s 2015 photographic series, ‘I AM ROYAL’

Her practice, which incorporates photography, video, performance and multimedia installations, tackles issues of identity, often referencing cultural and religious practice among Muslims, as well as South Africa’s “coloured” or “Cape Malay” community, both terms she doesn’t consider to be appropriate in identifying what she proposed should be called a “creole community”.

It was her latest video art piece that sparked the idea to make her work accessible to the thousands of taxi commuters who might otherwise not see it. “After I made the film I thought, ‘okay, so the film is going to the Smithsonian in Washington…It’s here, it’s there’, but the place that inspired it has no access to it; that made no sense to me, I felt uncomfortable. And I thought, How can I get this to be seen? And then I thought, well, the taxi makes sense. Because the taxi was my inspiration in the first place. If it wasn’t for the taxi the work wouldn’t exist,” Petersen explains.

The taxi will continue its usual commute, covered in the artwork for six months. The project was launched as part of Cape Town’s (Un)Infecting the City festival. Image: Knut Otto

Through the use of vinyl, the exterior of the taxi is covered in stills from Petersen’s film, named Kassaram, a “Malay” word that Petersen says she understands to mean “when things are upside down, out of place, or things aren’t as they should be. I don’t know if there’s a sort of ‘proper meaning’, but that’s the way we understood it. My great grandmother would say to me, ‘I’m awake and your bedroom still looks like a kassaram, or this place is a kassaram.’ So that’s what I called the film because things are not as they should be; the way we live is not right.”

The film, which will play in the taxi for a period of six months, is a 12-minute long audio-visual feast that takes viewers through several “stereotypes that were used to create and impose an identity on us as a community,” Petersen explains.

“I researched old paintings, old drawings, you know… it’s about that representation up until Irma Stern. You know you always get the typical ‘Malay’ lady in the Medora, the Moslem teacher with the students. So it’s all these stereotypical things which are drawn from particular paintings and drawings, and how a creolised community had been divided through the arts; how the arts and media and image-makers in a sense, have created who we are, supposedly, to the world and represented us in a particular way, and how this representation has deteriorated to suit different agendas over time.”

Indeed, in the first few minutes of the video, Petersen is seen in several costumes, playing out happy dancing stereotypes reminiscent of the characters depicted in some of Stern’s paintings from the 1920s. Her husband and her children are also seen playing the role of the “Muslim teacher with the students”, while a choir plays string music in the background, specifically the music of the Cape Malay choir.

A screenshot from Thania Petersen’s video art film, Kassaram.

“The Cape Malay choir is quite a thing. And the reason they rock their bodies when they sing, is because the movement is reminiscent of the ocean and the movement of the ships that people were brought on across the Indian Ocean; and they sing in the same tone that we make dhikr [Islamic devotional acts, in which phrases or prayers are repeated]. That in itself is layered…it’s a long story.”

Petersen explains that while the style of the music was not new, it was I.D. du Plessis — the early 20th century Afrikaans poet and writer, and head of the Institute of Malay Studies at the Cape Town University in the early years of Apartheid — that formalised it. Du Plessis went on to become secretary and adviser for Coloured Affairs. He played a significant role in establishing Cape Malay cultural identity, such as the designation of Bo-Kaap as a Cape Malay area under the Group Areas Act.

As reported by Rebecca Davis, who wrote in 2019: “But Du Plessis was not some non-racial altruist hiding in plain sight in the middle of a crazily bigoted government. His reasons for helping the Cape Muslims in this respect were, in fact, deeply racist. From his writings, we know that Du Plessis had an exotic, almost fetishistic view of the group he called ‘Malays’, whom he viewed as a quaint, spiritual, colourful, docile people who were a cut above all the other people of colour in the Cape.

“If the Bo-Kaap had social problems, he blamed them on the influence of Africans and non-Muslim coloured people in the area, writing in 1947: ‘Shebeens have sprung up in clusters, wine is brought in from Monday to Saturday… dagga smokers make the Malay Quarter unsafe, and an influx of natives has added to the housing problems of the Malays.’”

Says Petersen, “Using the music in this instance is all about the construction of being Malay and Cape Malay and being orientalised in an African landscape, to other us.”

It is also thinking that informs her aversion to the terms coloured and Cape Malay, preferring creole instead. As she explains it, “creole is more representative, it speaks to a people who belong and are from the space they are in, as opposed to being called Cape Malay which suggests that we are from elsewhere. Yes, our ancestry is from all over, but we exist in this space only and we are indigenous to it, because this was the start of this mixing in a sense. And in that sense it is an African creole, we are African, not Malay or European.

“You often hear creolised people identifying their ancestry as being German or Indonesian, it’s always from somewhere else. But the idea of creolisation doesn’t take you away from your ancestry. It acknowledges that but it still centres you and grounds you and gives you a sense of belonging to the space that you exist in.”

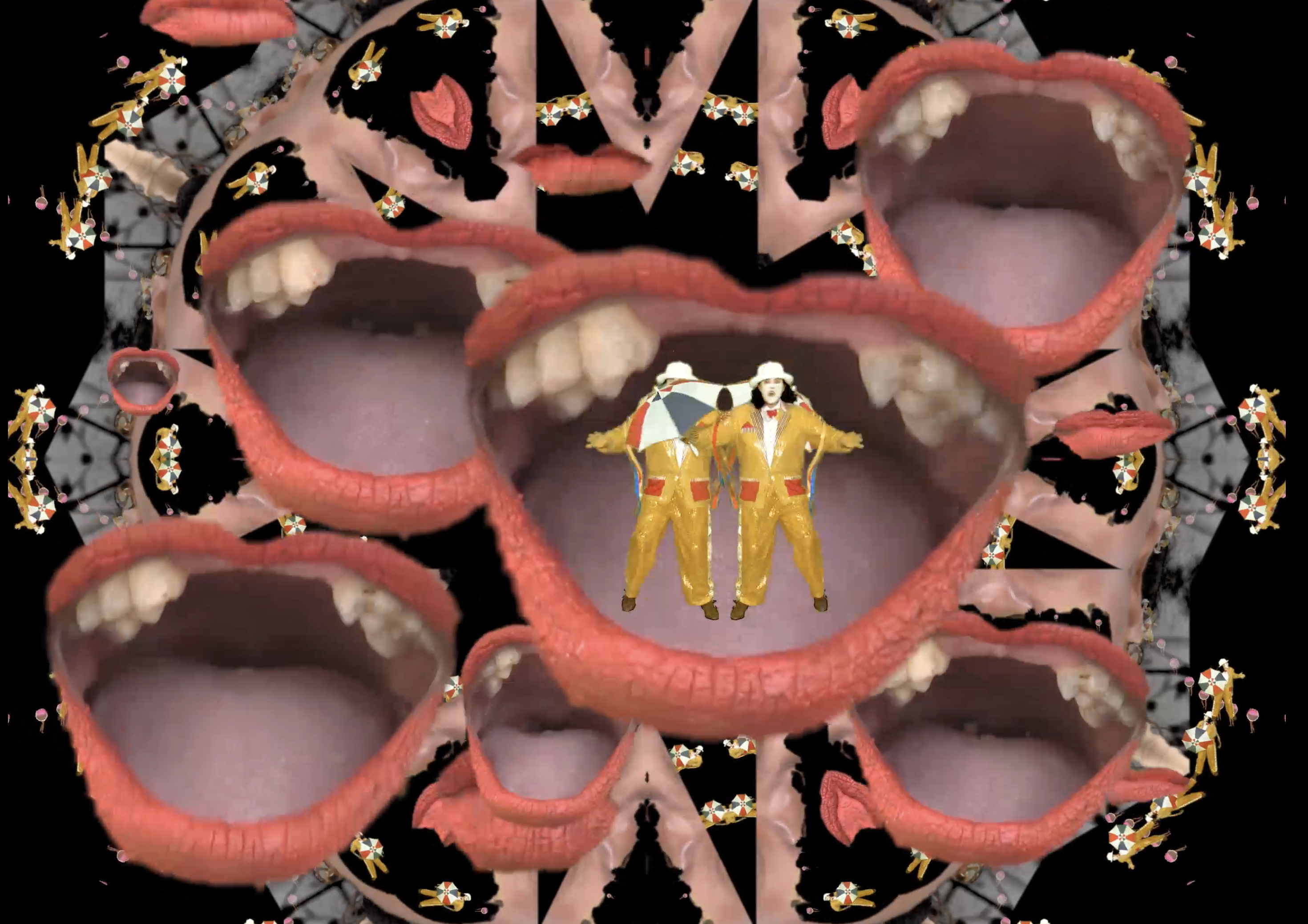

Throughout Petersen’s Kassaram, there are numerous images, each a reference to the history of the construction of “coloured” and “Cape Malay” identity. But in its third and final act, the mood and the sounds shift to something that gets progressively darker. At first, Petersen dances in a costume, such as the ones won by participants in the annual Cape Town minstrel carnival, to the eclectic sound of the music usually played at the carnival. Then the sound shifts into EDM (electronic dance music), followed a minute later by footage of the death of gang leader Rashied Staggie, who was kicked, shot, and burnt to death in the middle of the street by members of People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (Pagad). The image is juxtaposed with Petersen dancing in her minstrel costume, and images of red lips opening and closing, with missing front teeth, while the EDM’s bass thumps in the background, inspired by the sound favoured by taxis with bass-heavy speakers.

A screenshot from Thania Petersen’s video art film, Kassaram.

“When you see those mouths [in the film], that is when we begin eating ourselves. When we’ve been put so far into the ghettos, and we start killing ourselves and we start doing the work that oppressors did to us ourselves,” says Petersen.

In referencing familiar images, Petersen says she is looking to reframe some perceptions associated with them. For instance, the missing front teeth, a controversial practice of removing the front teeth, often derogatorily called a “passion gap”; while there are various theories among history buffs as to the history of the practice, one popular and oft-quoted origin story, which Petersen subscribes to, is that slaves removed their teeth to take back their bodies from the slave owners.

The taxi features elements of Thania Petersen’s Kassaram. Image: Amin Gray

Says Petersen: “A lot of people when they think of people in the Cape Flats pulling out their teeth, they associate it with gangsterism and ugliness. The way I understand the reasoning is that it was because in the days of slavery, they were branded on their teeth. So when they escaped, they pulled out the teeth, to cut themselves from the slave owners. This was like an act of liberation. The reason why I’m using this as an icon is because I realised that if you mainstream something, if you mainstream iconography, it loses that stigma of ugliness.”

She hopes that this will be a pilot for a programme that can spread across Cape Town and the country, with many more artists and taxis participating.

Petersen says: “We’re hoping that over the six-month duration of this first project, we will get more taxis on the road featuring work by more artists. That’s the big idea.”

Although the current taxi will continue transporting commuters on its route over the six month period, the project was launched as part of the Cape Town public arts festival, (Un)Infecting the City (previously Infecting the City, curated by Professor Jay Pather, who is also the director of University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Institute for the Creative Arts (ICA).

When Petersen embarked on the project, realising that she did not have the funds to bring it to make it a reality, she contacted Pather, who loved the idea and brought it on board as part of the festival.

“Jay really enabled the pilot taxi for the project that we’re hoping is going to go on until we take over the whole transport system of South Africa,” says Petersen. With the help from (UN)Infecting the City, Petersen was then able to get funding that would get the artwork on the taxi. However, she is clear that this is not a profit-driven initiative. “I’m not taking a salary out of this and neither is anyone else. Even the people that did the vinyl gave it to us at a [significant] discount.”

Hers is also not the only video that will be played on the 22-inch screen that has been installed in the taxi; filmmakers Khalid Shamis and Kurt Orderson’s have both “generously lent their films to [be shown] for free. Even going forward, I doubt if anybody’s gonna make money out of this, but I would like to get to a place where people will be compensated for their time and efforts, including the artists. I don’t want to phone artists up and say ‘come do this taxi but there’s no money for you’, that’s horrible,” says Petersen.

The pilot minibus taxi belongs to a husband and wife team of taxi entrepreneurs, Ziyaad and Fatimah Dyason. When she called them up and proposed the project, it turned out they were familiar with her work, and as a child, Fatimah used to play around Petersen’s uncle’s bakery in Mitchells Plain.

Thania Petersen (left) standing with taxi owners Fatimah Dyason (middle) and Ziyaad Dyason (right). Image: Amin Gray

“She told me ‘We’ve been following your work. We love your work. And of course, we will do this. How many taxis do you want?’. I was like, ‘Oh my god, this is amazing.’ And then her husband phoned me to say you can do whatever you like, we want nothing in return, except that we don’t have a loss of income and my drivers are not disturbed.’ And I was like, fair enough. And so they’re actually in a sense now patrons of the arts,” says Petersen.

As the project develops, Petersen hopes to have variety beyond visual art. “I am hoping to work with poets as well. Imagine a whole taxi with poetry; even stitching the poetry into the seat covers so that when you’re sitting there you can read; and then having the poetry readings on the screen. It’s endless. You could have theatre productions and dance productions on the screens. Imagine one day you can choose what taxi to climb into based on whether you feel like theatre or poetry or an art documentary that day,” says Petersen. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Fantastic project!

A worthwhile antidote to the layers of revisionism that cloaks the people of greater Cape Town. Thank you for this. Camissa.

How awesome and fantastic….i read the 1st paragraph and thought, why do we obsess about race and culture and bemoan endlessly our oppression, by I suppose, Our Masters.

Stereotypes, prejudice, perpetual apartheid thinking – to clarify; the more we strive to illustrate/express our unique characteristics that identify a culture, thereby highlighting DIFFERENCE thwarts the idea of all men being completely equal.

In most modalities. ‘those people do this, and those people are like that’…how does this serve the idea of the universal set of ideas that classify us as human beings? No matter race, culture, income level, history, skin colour, customs, preferences, religion etc…

Morgan Freeman put it nicely; “if you want to end the race problem, stop talking about it”. (simple)

However, the valuable, unique, inehritance and celebration of untold history, culture and modalities of the cape malay are beautifully expressed in this article. Thank you so much!!! Sincere gratitude to Thania.

This topic engulfs me consistently. I avert victimisation notions these days and look at life for all that has come and gone as part of the clockwork operations of the universe and conscious evolution. It is what it is. It was what it was.