SHADES OF THE BIG BLUE (PART TWO OF TWO)

Defenders of the deep: protecting our oceans

Overfishing and plastic pollution are big threats to ocean health, but climate change and ocean warming are drastically changing our marine ecosystems.

As mentioned in our first story, Seaspiracy and the environmental impact of fishing, Ali Tabrizi’s documentary Seaspiracy, released in March, is an in-depth, albeit controversial, exposé of the vastness of the problems the world’s oceans are currently facing.

But what is the situation in South Africa and what are some of the solutions being implemented to help solve some of the issues?

Management and policy

Marine biologist and WWF’s Environmental Behaviour Change Practitioner and WWF-SASSI (Southern African Sustainable Seafood Institute) Manager, Pavitray Pillay explains that because 50% of South African fish stocks are imported and 50% is exported, when it comes to management policy, South Africa has an extensive, well-outlined policy in the Living Marine Resources Management Act 1995.

However, based on the research done at SASSI coupled with Pillay’s experience, it seems that South Africa is still struggling with fisheries policy monitoring and enforcement.

Pillay adds that the government has to up its game with middle actors in the supply chain because regulations are not as rigorous for retailers and suppliers as they could be.

“There is still a lot of work to be done in these areas locally. You have to make sure you put up observers on boats, you have to make sure that they are reporting back, that data is coming back to fisheries, that that data is looked at with a critical eye and you have to have recourse if a fishery does transgress and it has to be recourse in such a way that it hurts the fishery because then they won’t do it again,” says Pillay.

Seaspiracy also trivialises and in some instances, fails to dive deeper into the work various NGOs and governments are doing, dismissing them as deaf and mute to the problems the oceans are facing and ‘allowing’ fishing industries to pillage the oceans.

“Tabrizi devalues the hard work that thousands of NGO experts, scientists, industries and governments have done for many many years; if we didn’t truly believe that we could have sustainable fisheries and well-managed resources in the ocean, we wouldn’t be doing the job we are doing.”

Your voice and your wallet hold power and these are choices you can make immediately. All of us acting, I like to believe, will have a cumulative, exponential impact that will help with change right at the source which is on and in the water.

Being in the WWF network but also having worked at a university and various programmes around the world, Pillay says this was “very disheartening” for her.

“I have seen firsthand what real success can look like when you get it right. When all of these people in these various spaces pull together and work together,” Pillay adds.

One case in point is WWF’s SASSI.

SASSI is not an eco-label. It is a voluntary compliance programme that, in South Africa, is working with major retailers like Pick n Pay, Food Lover’s Market, Spar, Woolworths, and the Shoprite Group to uphold their commitments to more sustainable seafood.

“It is what we call a time-bomb commitment which means by a certain time their seafood on the green list will be eco-label certified, or it will be within a credible fisheries improvement project. Bringing in a certified fishery is expensive so your middle to low-income retailer often cannot afford to have an MSC or ASC certified product on the shelf. So SASSI, although not an eco-label, offers an alternative way to trace sustainability,” says Pillay.

SASSI is working with many fisheries which are striving to be under improvement or are currently under improvement. This enables fisheries working with NGOs, government or a community to put measures in place to ensure that they have minimal environmental and social impact. Pillay explains that these improvements can include communication to ensure that fisheries don’t set lines at night, avoid using bird scaring devices and put observers and cameras on board as a monitoring technique.

The marine biologist also advises downloading the free SASSI app guide. The SASSI app allows you to check the sustainability of your seafood choice in real-time. All you need to do is look at the product labelling which should tell you the species’ common as well as scientific name, the species’ country of origin, and the capture or production method used.

The status of the fish you are wanting to buy will appear with either a green dot (‘best choice’), orange dot (‘think twice’) or a red dot (‘don’t buy’).

“If you see the fish is listed as red, make a decision not to buy the fish and to tell the retailer that it is on the red list and question them so that the retailer is aware that the species should not be available for consumption,” says Pillay.

“While no certification schemes can be 100% perfect whether it is a certification scheme for the oceans or for agriculture, it can be the best practice at the moment and that is what we strive for, it is what we want. As long as we can move and be agile with what is happening in the seas, with the fishing, there’s compliance and there’s enforcement…that’s why those standards exist, can you imagine if they didn’t?” she comments.

It is clear that there are problems around bycatch; there are issues around critical species like sharks, dolphins, whales and turtles; there are issues around human rights infringements; and there is illegal, unregulated, unreported fishing.

Pillay says this information is not new.

According to her, what’s needed now are ways in which monitoring of the supply chain can be solidified in order to find management, compliance and enforcement solutions that speak to one another. In addition, it’s vital that pressure is applied to retailers to commit to sustainability and refrain from selling illegally caught species.

“Your voice and your wallet hold power and these are choices you can make immediately. All of us acting, I like to believe, will have a cumulative, exponential impact that will help with change right at the source which is on and in the water. That means looking at innovations like aquaculture as a responsible, active source — not an irresponsible one. Know the consequences of your diets. And know that when an industry is no longer supported it is not just the industry that suffers but millions of people’s livelihoods are affected,” says Pillay.

“These decisions have knock-on effects with far-reaching consequences and unfortunately far more in developing countries than in developed countries. But there are things we can do about it and are doing about it, they’re just not as easy as not eating fish,” Pillay adds.

On plastic and ghost fishing nets

Ghost nets are commercial fishing nets that have been lost, abandoned or discarded at sea and are responsible for trapping and killing marine life or smothering coral reefs. These nets pose a problem because they are made from plastic which does not biodegrade.

Seaspiracy claims that at least 46% of plastic found in the ocean consists of fishing nets while playing down the problem of land plastic in the oceans — a statement inspired by a paper by Laurent Lebreton.

Pillay says that what we need to realise is that this number is modelled using only the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (the world’s largest collection of floating debris found in the North Pacific Ocean). In other words, this is not a number based on physically counting each and every ghost fishing net in the ocean.

A movement called the Global Ghost Gear Initiative has done extensive work across the world’s oceans, as well as in the garbage patch and estimates that fishing gear accounts for numbers closer to 10% to 20% of all marine plastics globally.

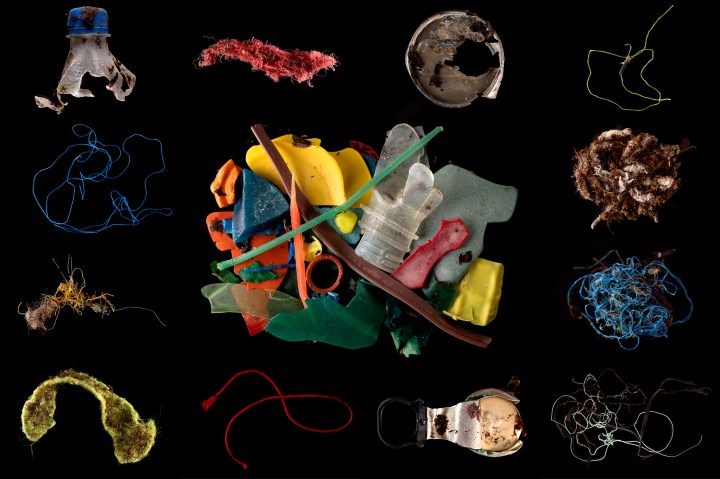

“I was weary because plastic is a problem. By no means is it any smaller in its scale of problem to overfishing in the years we’ve seen it. We know for a fact that 80% of all plastics in the oceans is land-based plastic consisting mostly of packaging, tyres, single-use plastics like straws, water and cooldrink bottles,” says Pillay.

While ghost gear and ghost fishing nets are perhaps not as big of a problem as Seaspiracy made them out to be, marine biologist and conservation coordinator managing the turtle rescue, rehabilitation and release programme at the Two Oceans Aquarium, Talitha Noble, points out that the more realistic number of 10% of all nets and 30% of all long lines becoming ghost gear, is still astounding.

“Ghost fishing is particularly dangerous to turtles because they are air-breathing and the nets drown them. Whilst turtles can hold their breath for hours at a time when they are stressed it is much harder and so they often drown quite quickly. We haven’t seen all that many incidents of entanglement. The reason for this I reckon is that most ghost gear is quite far out to sea and so when turtles are entangled, they will die before they (could) strand anywhere,” says Noble.

Image: Maryke Musson

Image: Maryke Musson

Pillay further explains that the danger linked to ghost gear is that it ‘continues fishing’. Because fishing nets are plastic (nylon) and light, these nets float and cause entanglements, which means sea creatures like seabirds, seals, turtles, dolphins and larger fish get caught up in the nets which can lead to suffocation.

A turtle has a harrowing time trying to survive, Noble explains, adding that “only one to two turtles in 1,000 make it to adulthood”. Apart from facing natural predators like sharks, seabirds and strong currents when growing up, the hatchlings and young turtles have another formidable predator to beware of: plastic.

Noble says that turtles are indicators of ocean health and that recent findings on plastic are not a good sign. From the research they have conducted at the Two Oceans Aquarium conservation facility, Noble says this season 342 pieces of plastic have been found to have been ingested by hatchling turtles. Thirty-three out of 52 of the rescued turtles have excreted plastic. One turtle, in particular, passed 46 pieces of plastic through its digestive system.

“Some of the hatchlings have eaten more plastic than protein in the first two to three months of their life,” comments Noble.

The tale of Annette (Annie), the 52kg loggerhead turtle has become somewhat of a legend at the Two Oceans Aquarium. Annie was found by the Kommetjie National Sea Rescue Institute (NSRI) team in 2019 stranded on the beach tangled up in a ghost fishing net together with a seal. The seal was cut loose and returned to the ocean immediately. However, Annie required serious attention and entered into the Aquarium’s rehabilitation programme — a process that would last one and a half years until her release at the beginning of this year.

“In South Africa, you find that our trawl industry will actively go and look for their trawl net if it detaches because it is so expensive to lose. There are other fishing companies that go and send their broken nets and other fishing gear to be fixed, or overseas to a country where it can be recycled,” Pillay points out.

Collecting waste and recycling

Good On You — a platform that provides fashion brand ratings and publishes comprehensive evaluations of fashion brands’ impact on people, the planet and animals — mentions on its material guide an innovative textile yarn called Econyl. The yarn gets a “good” rating for its recycled and regenerated characteristics.

Econyl is a recycled, regenerated nylon yarn made from synthetic waste like fishing nets, industrial plastic and waste fabric supplied by Italian firm, Aquafil. The regenerated nylon yarn is used for textiles and in the automotive sector as carpets.

“Econyl regenerated nylon is a yarn entirely made from nylon waste such as fishing nets, fabric scraps, old carpets, plastic components (so, not only fishing nets but 100% from nylon waste). Most of the fishing nets we use in the process are coming from fish farming and only a small amount are ghost-nets,” explains Aquafil customer communications support officer, Martina Santoni.

Santoni adds that Aquafil collects Nylon 6 waste from all over the world through different initiatives and projects such as the Healthy Seas initiative, where volunteer divers recover abandoned or lost ghost nets from the bottom of the seas in Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Greece, and Croatia. Similarly, Net-Works, which was founded by Interface with the Zoological Society of London, is a social initiative to empower coastal communities in the Philippines and Cameroon to collect and sell discarded fishing nets. Furthermore, Aquafil Carpet Recycling facility — established in Phoenix in the US — allows Aquafil to recover nylon waste from old carpets.

According to Good On You, this model of regeneration “focuses on six steps that form a closed loop which uses less water and creates less waste than traditional nylon production methods”.

The process involves the collection of waste (fishing nets, fabric scraps, old carpets) which is then washed and shredded, depolymerised (deconstructing the composition of a substance) to extract the nylon, polymerised (combined) and transformed into yarn, which Santoni says is “naturally white”, and made into various textile products.

“Nylon 6 is a very special plastic material. Thanks to its chemical composition (the structure of the molecules) we can regenerate it an infinitive number of times without losing performance and qualities. Indeed, Econyl regenerated nylon performs exactly the same as standard nylon from fossils and could be regenerated infinitely,” says Santoni.

While Good On You pegs Econyl as an overall “fantastic initiative that is helping to clean up our waterways and repurpose trash that would otherwise end up in landfill”, there is one pitfall linked to the textile yarn and that is the issue of microfibers, that are plastic particles that synthetic fibres release in a machine wash or dryer.

Image: Atlas Label (Photograph: Alex Oelofse)

An example of a local brand using ECONYL is Cape Town-based swimwear Atlas Label, founded by Cristina Rovere; the label is committed to producing high-quality, environmentally-friendly pieces from considered fabrics and materials and is producing their locally-made swimwear range from Econyl. Luckily, swimwear does not require regular washing but Atlas Label’s swimwear comes with care instructions that specifically state to not machine wash or tumble dry their items.

Another threat to our oceans: climate change

Researcher and Data Analyst at the Beach Co-op — a South African non-profit clean-up and ocean ecosystems awareness project — Dr Ffion Atkins also points out that climate change is massively affecting the oceans.

Atkins explains that the ocean can buffer a lot of the impacts of human activity and that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports that the ocean has already absorbed 20-30% of excess atmospheric CO2, but this comes with profound and potentially devastating impacts.

“Overfishing and plastic pollution are certainly big threats to ocean health, but by far the most significant threat is global (and ocean) warming, and how rapidly things are changing. Ocean acidification, reduced primary productivity and dramatic shifts in marine food webs (from phytoplankton to apex predators) are just some of the impacts caused by climate change,” Atkins says.

“Species will not only have to adapt to a changing thermal environment but to increasing acidity as well. Now add other major pressures such as overfishing or plastic pollution on top of that and we radically reduce the resilience of marine ecosystems to cope with (and adapt to) the unprecedented rate at which climate change is occurring,” adds Atkins.

The team behind The Beach Co-op has developed the Marine Debris Tracker app as a tool that makes data collection easier for the non-profit, while connecting data collected by The Beach Co-op to a global community of marine debris data collectors, to better understand the litter problem and how to relieve it. The Beach Co-op says that most of what is recorded in their beach cleanup initiatives comes from the 12 most commonly found plastic items on beaches, known as the ‘Dirty Dozen’ (46% of total items) or other items of plastic (43%).

“Every time someone uploads data, they are contributing to a global database and ultimately to a better understanding of plastic pollution. We focus our attention mostly on the Dirty Dozen. These are on-the-go food packaging such as sweet wrappers, lollipops, water and cool drink bottles and mostly come from land-based sources (especially around urban areas),” Atkins says.

“We do also record other items such as rubber, glass, fishing gear, personal hygiene and other plastic containers etc. but it seems we are not recording as much of that. Fishing gear accounts for 1.5% of all Beach Co-op data collected on the Marine Debris Tracker app. However, it’s important to note that our data will be biased to the Dirty Dozen because that is what we focus on,” adds Atkins. DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.