ANCIENT JOURNEYS

René Caillié’s incredible journey to Timbuctoo

When René Caillié was eight his father died in prison and his mother followed three years later. Living with his grandmother and sister in the French village of Mauzé-sur-le-Mignon, he dreamed of escaping through the pages of his favourite book, ‘Robinson Crusoe’.

“It inflamed my imagination,” he would write. “I felt an ambition to signalise myself by some important discovery springing up in my heart.”

At 16 with a few francs in his pocket he signed up on a naval ship heading for Saint-Louis. From there he took off for Dakar, then headed across the Atlantic to Guadeloupe, where he heard of Mungo Park’s fateful journey down the Niger River (he drowned).

In 1824 Caillié returned to Senegal with a plan to visit the African interior. The Paris-based Geographical Society was offering a 10,000-franc reward to the first European to see and return alive from Timbuktu, believing it to be a rich and wondrous city.

He spent eight months with the Brakna Moors living north of the Senegal River, learning Arabic and being taught, as a convert, the laws and customs of Islam. Having saved £80, he joined a Mandingo caravan going inland.

He was dressed as a Muslim and gave out that he was an Arab from Egypt who had been carried off by the French to Senegal and wished to regain his own country. Christians in West and North Africa were hated and, had his true identity been found out at any point on the journey, he would have been killed.

***

René Caillié set out from Kakondy in April 1827 and crossed Upper Niger into the Kong highlands in what is now the Ivory Coast. He spent five months in the village of Tiémé recovering from malaria, then set off for the city of Djenné.

René Caillié dressed in arab clothing. Picture is opposite page 74 in: Caillié, René (1830), Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo; and across the Great Desert, to Morocco, performed in the years 1824–1828. Vol. II, London: Colburn & Bentley.

In a period given to large-scale Western expeditions flying imperial flags supported by soldiers and teams of black porters, Caillié travelled alone. He fitted in with local populations and learnt their ways.

In Djenné, he wrote in his secret diary, “I was informed that the great canoe which was to convey us to Timbuctoo was in the port and ready for our reception”.

He paid his passage in cowrie shells and his canoe joined a flotilla of about 40 boats heading downriver together as protection from pirates “who often board their boats and commit acts of violence and robbery”.

Soon they were pounced on by a tribe called Soorgoos who demanded tribute of food and these tribute raids were to continue all the way to Timbuctoo. Being neither a local Moor nor African, Caillié was often treated little better than a slave and had to virtually beg for food.

Despite the danger of detection, he documented the journey meticulously, often writing hidden under a woven mat. He always held passages from the Koran beside his diary. If caught he could say he was transcribing it to learn it by heart.

Everything fascinated him, especially the canoes. “A vessel of 60, or 80 tons is about 90 or 100 feet long, 12 or 14 broad at midships and draws six or seven feet depth.

“These canoes are generally fragile and it is astonishing how they bear the heavy cargoes with which they are laden, which consist of rice, millet, butter, honey, onions, pistachios, cola-nuts, stuffs and various kinds of preserved articles. In addition to their cargo they frequently have on board 40 or 50 slaves. They scarcely make two miles an hour.”

Caillié, with limited cowrie currency, lived on a diet of dokhnou (a drink of millet flour, honey and water) and dried fish.

Postcard 380 by Edmond Fortier. View of the house where René Caillié stayed in 1828 during his visit to Timbuktu, Mali.

After weeks of extreme heat to which he was unaccustomed and near starvation, the Frenchman arrived in Timbuctoo. “On entering this mysterious city, which is an object of curiosity and research to the civilised nations of Europe,” he wrote, “I experienced an indescribable satisfaction. This duty being ended, I looked around and found that the sight before me did not answer my expectations.

“The city presented nothing but a mass of ill-looking houses, built of earth. Nothing was to be seen in all directions but immense plains of quicksand. Timbuctoo and its environs present the most monotonous and barren scene I ever beheld.”

Caillié reasoned that if he returned to West Africa the way he’d come, critics would claim he never got to Timbuktu, so he decided to join a caravan crossing the Sahara to Morocco. He bought a camel and, with midsummer heat in the 40s and feeling ill, he set off northwards with a 800-camel slaver caravan.

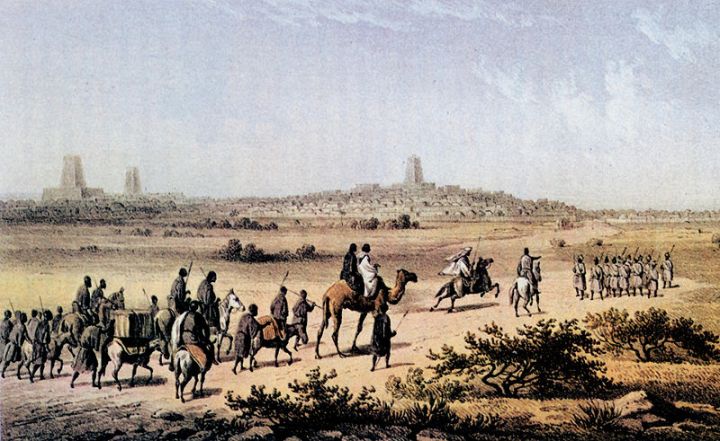

Poster Print of Mali/Timbuktu 1870. General view of Timbuktu. Image:

© Mary Evans Picture Library

From the outset he was treated badly by the Moors. “When the common people of these countries meet with a stranger, they think they may insult him with impunity,” he complained. He was amazed, however, at their navigation skills.

“It is by the pole star that the Arabs are guided in all their excursions through the desert. The oldest caravan conductors go first, to lead the way. A sand-hill, a rock, a difference of colour in the sand, a few tufts of herbage, are infallible marks, which enable them to recognise their situation.

“Though without a compass, or any instrument for observation, they possess so completely the habit of noticing the most minute things, that they never go astray, though they have no path traced out for them, and though the wind in an instant completely covers with sand and obliterates the track of the camels.”

FRANCE – CIRCA 1999: a stamp printed in France shows Rene Caillie, French Explorer of Africa, the First European to Return Alive from the Town of Timbuktu, circa 1999.

The journey nearly killed him. After many months, half-starved, dehydrated and unwell, he staggered into Fez, swapped his wasted camel for a donkey and headed for Tunis where the French Consul took him in and had him bathed, fed and reclothed.

On 28 September 1828, he set sail for Toulon and fame. He collected his prize of 10,000 francs from the French Geographical Society, wrote an elegant, three-volume account of his travels, received the Legion of Honour medal, a pension and other distinctions. He married, bought a house and settled down. His luck didn’t last. Ten years after returning, aged 39, he died of tuberculosis, his constitution weakened from deprivations suffered on the Sahara journey. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.