GARDENING

Bringing life back to the sterile suburban oasis

It’s an irony that many of our colourful and lovingly manicured suburbs are largely bereft of the birds, bees and wildlife that once enriched the lives of our parents and grandparents.

The thing is, you don’t have to look hard to discern the reason for this impoverishment. Quite simply, many modern gardens look neat and beautiful to many of us — but there is almost nothing for wildlife to eat. Nor many suitable places to hide or nest.

For several years I’ve taken a stab at reforming our garden (and my mindset) by gradually replacing exotic plants with indigenous ones, to make a bit more place for nature in the tiny urban space where I have a measure of direct control. To the dismay of a succession of our garden assistants, I have prohibited any poison or labour-saving weed-killers, so all weeds are removed manually and laboriously from bricked or paved areas.

But last week, relaxing outside just before sundown, I realised just how little has been achieved.

Sure, many of the exotic plants and alien invasive species are gone. But the old routines continue more or less every week. Hedges get clipped, the lawn is mown, ‘weeds’ are removed and fallen leaves swept away. Old habits and mindsets are difficult to break.

Like many other gardeners, I suspect, my mind remains hardwired by the compulsion to manage and to engineer my surroundings. Gardens are also uniquely personal havens, spaces that offer us an opportunity to express our sense of artistry and preferences within a wider world where choices are more limited.

The Flowers at Fancourt. George, South Africa. Image: Esteban Castle / Unsplash

Yet, despite this sense of failure and frustration, I have resolved to try a bit harder this year in the hope that my many neighbours and other gardeners across the country might also give some thought to collectively redesigning, reimagining and re-wilding their gardens.

It will not change the world overnight — nor halt the rampant, global decimation of much larger wild places by humanity — but just take a peek into your garden or those of your immediate neighbours. Chances are that many are still filled with plants from another continent.

Fragrant roses or camellias from the Far East. Lavender, oleander, jasmine and sage from Mediterranean Europe or a host of colourful shrubs, cacti or plants with delicately variegated leaves from Central and South America. Or aliens like frangipani, bougainvillea, poinsettia, bromeliads, dahlias or daffodils.

Kafui Yevu / Unsplash

Close up of trailing Namaqualand daisy (Dimorphotheca fruticosa). (Photo by Gallo Images / Home)

Fragrant and lovely to look at perhaps — but not much good for the survival of local birds, butterflies, insects and other animals that evolved over millions of years to be sustained by local fruit plants, local insects, local grasses, local flowers and local natural habitat.

This could change.

“If another 100,000 homeowners did just one wildlife-friendly act, just imagine the positive impact this would have on our urban wildlife …. Just plant an indigenous tree or shrub. And if you live in a flat, grow a bunch of (local) plants on your window sill or balcony,” indigenous gardens guru Geoff Nichols remarks in the wildlife handbook Bring Nature back to your Garden, first published in 1995 by Durban indigenous gardening champions Charles and Julia Botha.

The Bothas — who stopped using poisons and pesticides 30 years ago — say that transforming gardens from ecological deserts into biologically richer spaces is a slow process and does not have to happen over a single weekend or a single season.

“Don’t expect results overnight. Not only does it take time for plants to grow, but wildlife has to discover them. It is only the gardener who wishes time away in the desire to achieve results. To bring nature back to your garden you have to be patient,” they advise.

Pink proteas in a garden in Cape Town, South Africa. Image: Laura Flint / Unsplash

It can be done in stages, as time and finances allow, with the emphasis on planting a wide variety of shrubs and trees that provide fruit, nectar, seeds — and which also attract insects.

Durban bird lover Crispin Hemson, who lives next to the Pigeon Valley Nature Reserve, also suggests moving towards more “calculated neglect”, where gardeners are willing to tolerate more wild messiness.

For example, several bird species love to forage in the leaf litter that is too often raked away fastidiously in most gardens.

And when selecting new indigenous species, the advice from Charles Botha is to choose plants that are not just indigenous to South Africa – but indigenous to your particular area and climate.

In our garden, I have planted several aloes, thorn trees and other indigenous species from northern Zululand which remind me of some of the wild places that I love most — though I realise that this is not far removed from establishing an English country garden in Africa.

My wife would also like to see more colourful flowers and is loath to fell and replace one of our biggest and oldest (exotic) trees — so we have disagreements and reach compromises.

All the same, our garden is still largely devoid of indigenous food trees for wildlife.

Image: Jametlene Reskp / Unsplash

So, on the sly, I’m plotting to plant some small Natal figs (Ficus natalensis) in the clefts of some of the remaining exotic trees. Over time, these small figs will send out roots that will eventually strangle the exotic hosts and provide a larder of tiny, tasty figs for birds, bats and other small animals.

I’m also planning to set aside some (initially small) zones of the garden where seed grasses and other ‘weeds’ can run wild.

And then there is the question of chemical poisons.

Recently, Charles and Julia Botha have been re-emphasising the need to avoid any synthetic pesticides, as most exotic “pests” can be controlled without resorting to any kind of chemical pesticides in the average urban garden.

Image: Jonathan Rautenbach / Unsplash

Image: Thyla Jane / Unsplash

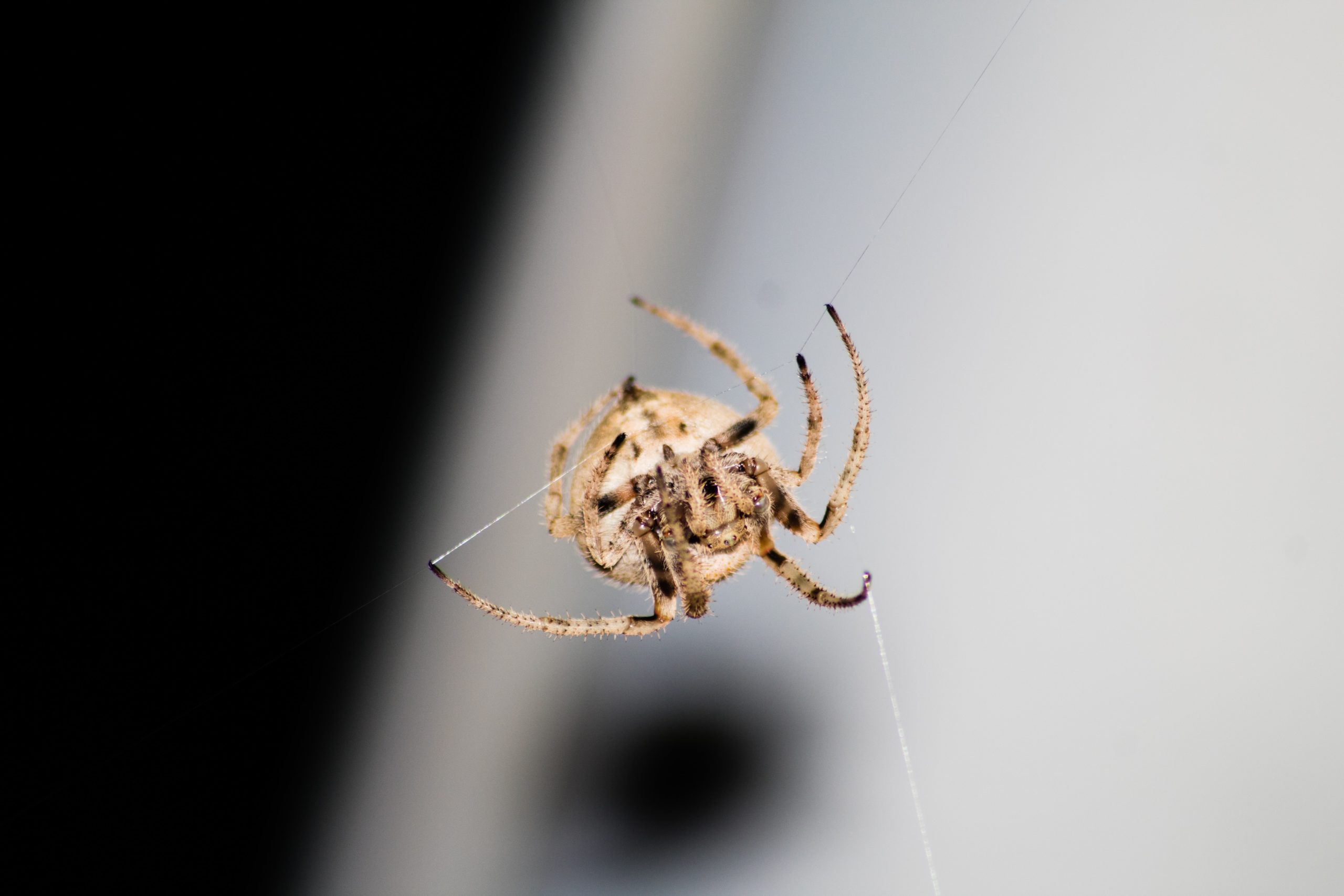

They note that insects are an essential food source for most garden birds and their fledgelings — including the fruit-eaters and nectar-eaters. So, if you don’t have a garden rich in insect life, the variety of bird species and other small wildlife will most likely remain low, unless there is a good insect food source nearby.

“There are many natural ‘controllers’ of pests in the garden in the form of spiders, mantids, centipedes and a host of other small creatures. However, when poison is used, these predators are destroyed along with the pests,” says Charles.

“Because we have not used any poisons whatsoever in our Durban garden, not even the supposed environmentally-friendly ones, for over three decades, we have an abundance of predatory insects.

“These, together with the birds, ensure that we have no problem at all with the usual garden pests such as aphids, ants, cutworms, crickets, caterpillars, etc. Some imported pests, like mealy bugs, are promptly removed by hand, but absolutely no indigenous creature is ever killed.”

If any of these ideas strike a chord, it might be worth consulting local experts and indigenous nurseries on what plants to choose when re-wilding your garden. DM/ ML

One useful starting point is buying the latest region-specific copy of Bring Nature Back to your Garden directly from the publisher: The Flora & Fauna Publications Trust, via Marylynn Grant [email protected] or visiting Anno Torr’s website.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

There is not enough benign neglect in the world.

There are a few no-maintenance, evergreen, perennials that are bird, bee and butterfly bombs … tops is ribbon bush (hypoestes aristata), especially in KZN

If space permits, a pigeon wood (trema orientalis) will bring bird life and spark a veritable indigenous green revolution around the tree …

Bulb fennel is another brilliant plant that sows itself, thrives even in the most solid clay soil with little watering, provides delicious bulbs (above ground) when sown first time AS WELL AS every time when cut down and allowed to grow out again (my favourite is fennel combined with lots of onions, tomatoe, garlic and chorizzo, serve with pasta, parmesan) . The flowers are a zooming daily party for every kind of bee and wasp, varieties which one often does not even know. It will flower for a long time on different levels for many months providing valuable pollen. The seeds are delicious breath fresheners and often used in Indian cooking for curries etc.

We have left a large part of our 2 acres in a small Zululand town to just be. But leaving be is not the same as neglecting – there is the never ending waging of war against the bugweed, lantana, jigijolo, litsia…..etc!

Another great resource is Gardening for Butterflies by Steve Woodhall and Lindsay Gray. Although butterflies are referenced in the title it is, infact, about gardening in a way that creates habitat for all creatures. In these difficult times our gardens, nature reserves and parks can be places to quieten the mind and offer peace and reprieve.