MATTERS OF OBSESSION

The outsider’s outsider: Andy Warhol, Fame, Glamour, Money, Art

Andy Warhol is a most curious figure in the history of Western art. No one could have been more different from the stereotype of the artists of the early 20th century, those figures obsessed with questions of aesthetics, the role of art in society, and concerned about larger questions about the future of humanity.

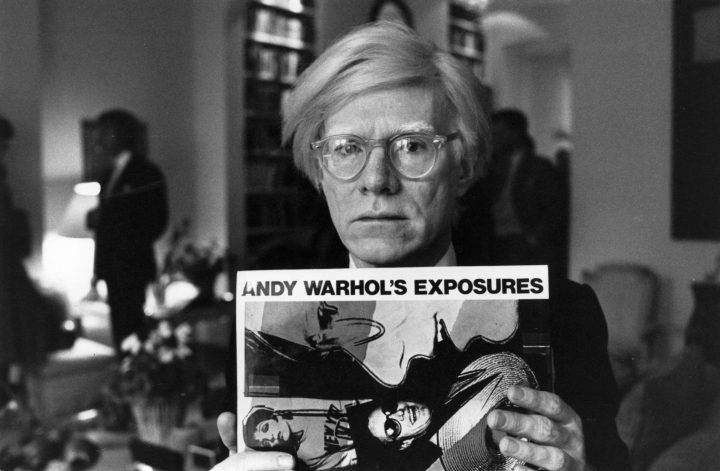

Andy Warhol was, from the start, concerned about fame, glamour and money, devoid of a philosophy of art – despite his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. And yet, it was Warhol, more than any of his contemporaries, who moved art from the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock to pop art, in the process replacing modernism, with postmodernism still playing itself out today.

The arc of Warhol’s life can be easily summarised: He was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928, the child of Czech immigrants. He was his mother’s favourite, his father being away for extended periods working in coal mines and on construction sites. He completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1949, after which he moved to New York, where he became a highly successful commercial artist, producing window displays and adverts for large companies for a decade.

He painted shoes for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, and designed footwear for manufacturer Israel Miller, graduating to LP album covers for the music industry.

In New York, Warhol was exposed to new trends that were pushing abstract expressionism off the stage. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein and others were beginning to produce works that would kick off the pop art movement.

In thrall to Rauschenberg and Johns, Warhol was not happy with his commercial success, and wanted to be recognised as a serious artist. He had an abiding respect for Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists, and he wanted to do something akin to what Rauschenberg and Johns were doing. Johns’s renditions of the American Stars and Stripes flag were pregnant with meaning, liable to be interpreted as patriotism but also as critique of US imperialism.

Warhol canvassed friends about ideas worth pursuing, ideas that would be different from those of his pop art peers, with one friend suggesting cans of food and dollar bills. Warhol’s big move was a series of works on these same themes: The Campbell’s Soup Cans, Dollar bills, Brillo boxes – all presented en masse, replicated and laid out next to each other, the Brillo boxes turning any gallery space into a supermarket floor. Indeed he participated in an exhibition that presented itself as a supermarket display.

A spectator walks past “Campbells Soup Cans” created in 1962 by artist Andy Warhol at the Andy Warhol retrospective exhibition February 5, 2002 at the Tate Modern Gallery in London. (Photo by Sion Touhig/Getty Images)

Between 1959 and 1961, “the seeds of a visual and indeed a cultural revolution were planted”, says philosopher of art Arthur C Danto in his book Andy Warhol. “A successful commercial artist became a serious avant-garde artist,” and the art world recognised the transformation.

Warhol’s Death and Disaster series was a turning point, presenting silkscreens of the electric chair as art, a modern recall of Hieronymus Bosch. The series began with the Marilyn Diptych, completed weeks after Marilyn Monroe died, and included car crashes and a suicide, among other gruesome images. Yet these were presented almost as advertisements, with a commercial feel.

This merging of the world of commerce with that of art was one of the significant effects of Warhol’s intervention. From there he ventured into “serious” art, and took to film in a big way.

By now Warhol had become an icon of the art world, not simply an artist but a celebrity much like those he admired and depicted: Marlon Brando, Liz Taylor, Liza Minelli, Elvis, Marilyn…

The Factory and after

Warhol had used assistants in his advertising work, and when he set up his Factory he adopted this commercial approach: He turned the production of art into a manufacturing process, unlike the process of individual production by 19th century artists. He reintroduced a process used in the Renaissance by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and others, who trained apprentices to undertake various tasks and acquire skills. Yet Factory works would be signed by Warhol, or more often by his mother, Julia Warhola, never by the apprentices.

Crucial to Warhol’s process was the silkscreen, a technology that allowed copies to be made with slight variations in each reproduction. This also allowed for sales to exceed the kind of transactions involving single works of art: Signed copies would allow for economies of scale.

Warhol’s Factory, meant to replicate the Hollywood studio and star system, was a magnet for deviants, those who failed or refused to fit into “straight society”. Addicts and misfits converged on his premises, a development that suited the supreme misfit, who provided a home to people who would honour his unwitting dedication to difference.

Warhol developed a following and became the centre of a movement in the arts that included film, photography, music and various forms of painting, resulting in what came to be known as Happenings. He was a facilitator and enabler, encouraging behaviour frowned on elsewhere, making connections between different disciplines and skill sets.

The Velvet Underground, one of the most innovative rock groups of the 1960s, was to introduce a certain nihilism into the Factory, although this was already part of Warhol’s makeup, evident in his Death and Disaster series. The band would become an inspiration for musicians who rejected the commercialism of more mainstream pop-rock music.

This was also the period that gave birth to the “superstar”, a phenomenon created by Warhol himself, one of the first being Edie Sedgwick, the haunted figure at the heart of the Factory who died in 1970 after a short and tragic life.

A photograph of Edie Sedwick is displayed at the Edie Sedgwick Exhibit opening party at Gallagher’s Art & Fashion Gallery on February 2, 2005 in New York City. (Photo by Donald Bowers/Getty Images)

Warhol’s relation to Edie, as she was known, has been the subject of much speculation, as well as a movie, Factory Girl. Warhol was captivated by her aura, her beauty and her energy, and not least her relatively aristocratic origin and network. Edie, coming from a family linked to those who arrived on the Mayflower, was a troubled being who had been abused by her father and lost two brothers to suicide. For a short time she and Warhol were inseparable, Warhol allegedly promising to make her a movie star. But it all went sour, and Edie’s descent into a drug-fuelled delirium would destroy her.

There were other dangers that lurked in the process of cultivating outsiders.

In June 1968 Warhol was shot by radical feminist Valerie Solanas, who was convinced he had stolen her script. A founder of the magazine SCUM (Society for Cutting Up Men), she believed men should be exterminated.

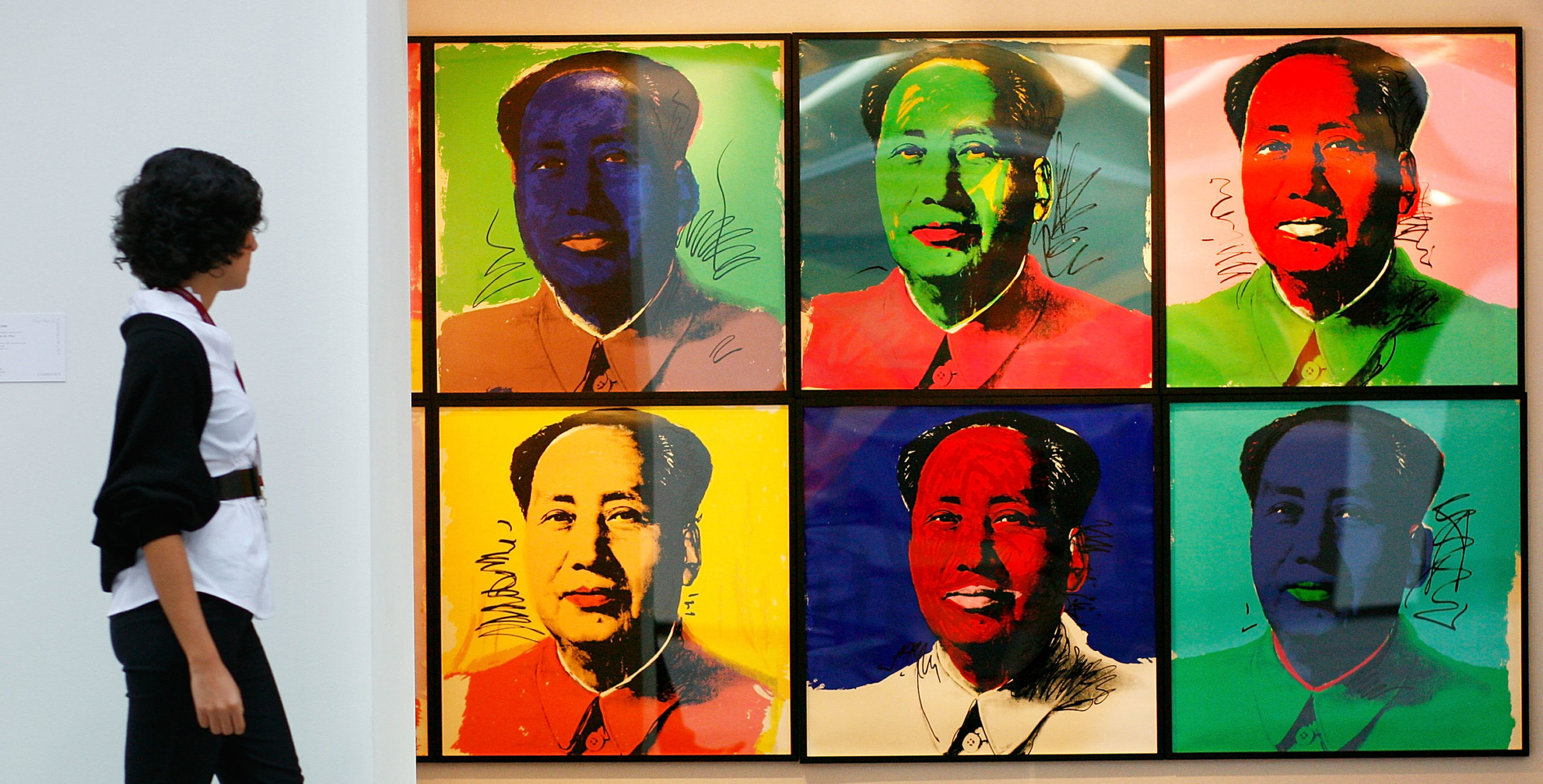

Warhol never really recovered from that near-extermination, but he got back to work a few months later. By the 1970s Warhol had “made it” – he was not only recognised as an artist but an icon, as Danto wrote. He cultivated famous personages and produced their portraits, from the Iranian dictator to one of Mao Zedong – who he did not meet.

Andy Warhol’s ‘Mao’ is displayed at Christie’s on February 4, 2008 in London. Christie’s Post War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale takes place in London on February 6, 2008. (Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

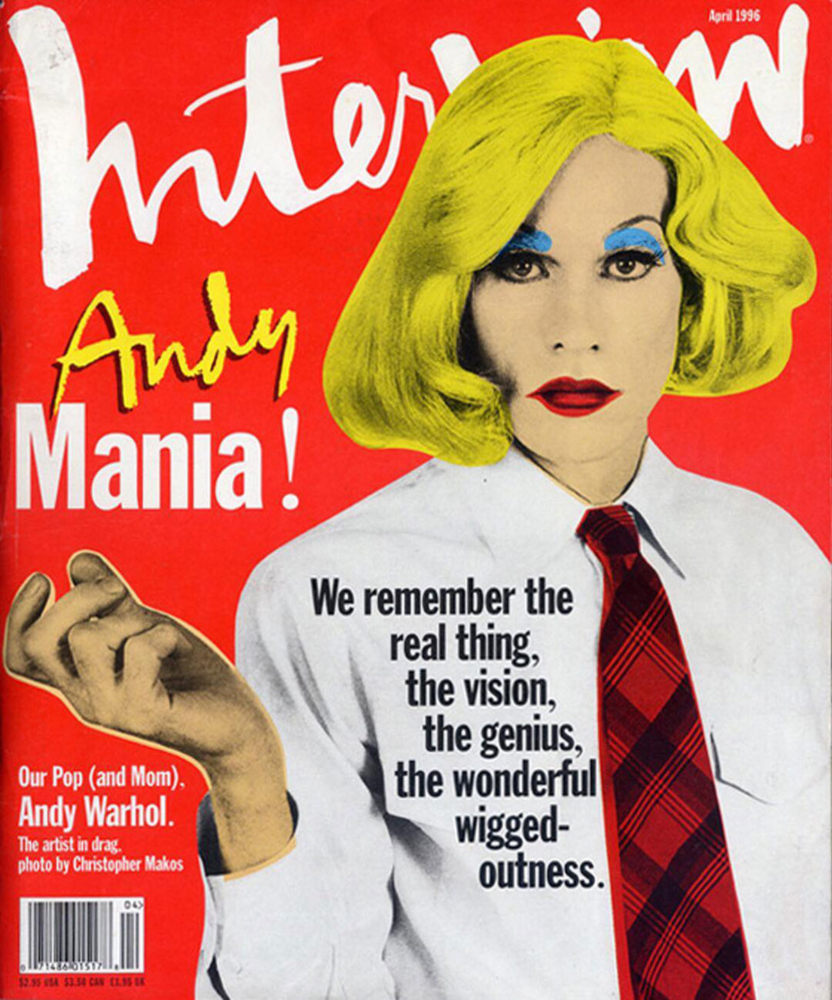

He began publishing a magazine, Interview, and brought out his book, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. It contains a series of reflections on Love, Beauty, Fame, and a few asides on Elizabeth Taylor. On Fame, he says:

“The people who have the best fame are those who have their names on stores. The people with very big stores named after them are the ones I’m really jealous of.” Hardly a philosophy of life, but revealing nonetheless.

Andy Warhol, photographed by Christopher Makos, on the April 1996 cover of Interview. Image via Interviewmagazine.com

He was a frequent visitor to Studio 54 as disco displaced rock music and brought a more hedonistic cocaine flavour into the music scene – very different from the more innocent sexuality of the flower power generation.

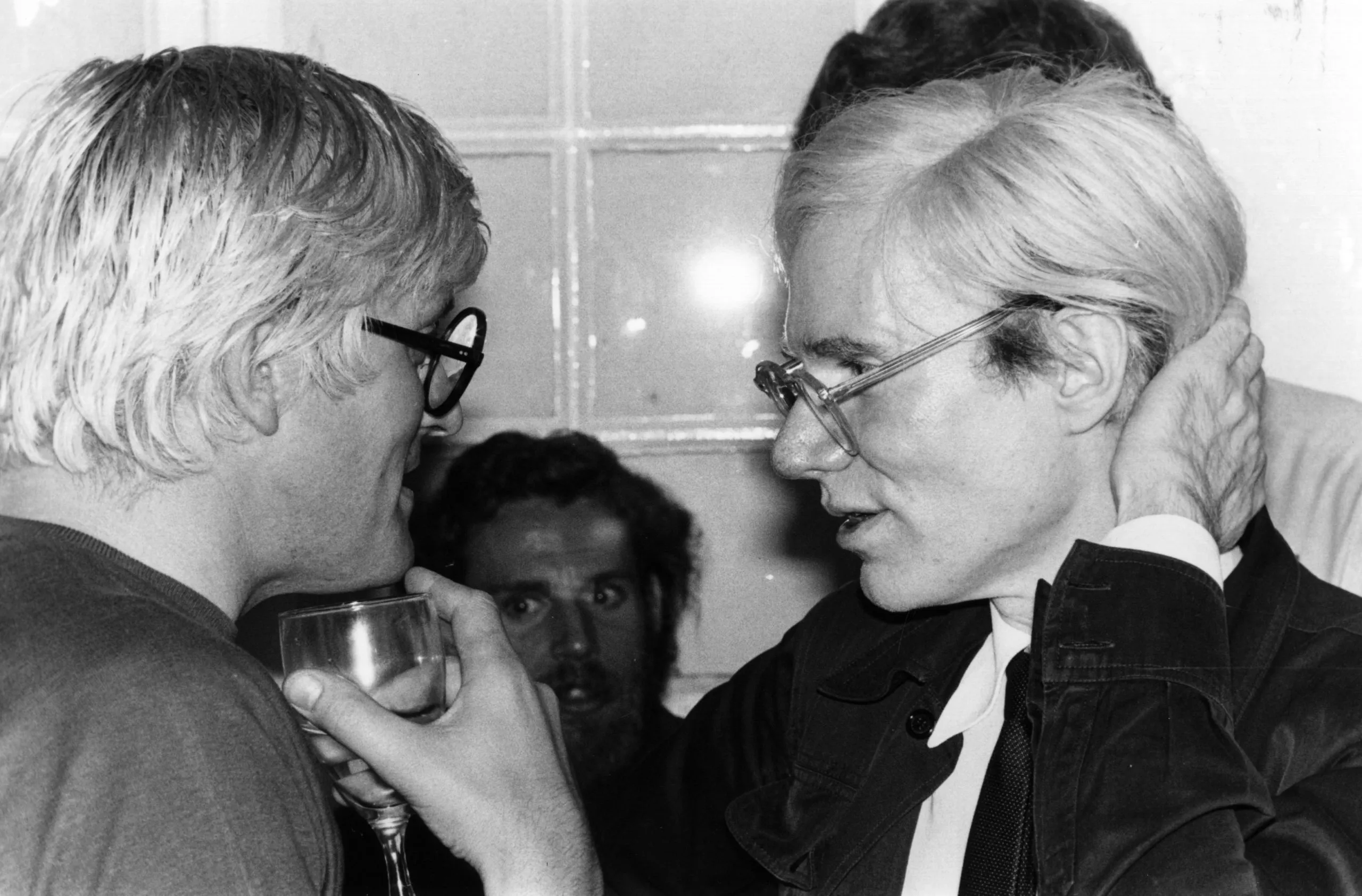

In the 1980s he worked with Julian Schnabel and David Hockney, and became a father figure to young Jean-Michel Basquiat. The pair produced collaborative works in 1984 and 1985, with Warhol constructing a work before it was defaced by the young maverick. They fell out when critics perceived Basquiat as Warhol’s “mascot”.

1976: English painter David Hockney, (left), and Andy Warhol. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Nevertheless, Basquiat was deeply affected when Warhol, at 58, died suddenly in February 1987, and his own death followed about a year later.

The Warhol persona

Warhol was a strange character, with a counterintuitive sensibility. While most would shun superficiality, he regarded it as something of value, pointing to the supposedly evident horrors of authenticity. Warhol hated scrutiny, and would often lie about his life – his origins, his beliefs, his very self. He hated the possibility of humiliation, which came naturally with fame, and he was gay, a fact he revealed in the subjects of his earliest films. Blow Job, for instance, focused on the face of a man undergoing fellatio. Averse to humiliation, he nevertheless laid himself open to it.

Andy Warhol’s first self-portrait (estimated £5-7 million) goes on view at Sotheby’s on June 23, 2017 in London, England. (Photo by Michael Bowles/Getty Images for Sotheby’s)

He was also frank about what he regarded as the vacuity of his life, it’s lack of content. Much of his work focused on the concept of nothingness – the emptiness of his obsessions: Celebrity worship, consumerism. He had a mania for collecting exotic objects.

He spent hours talking to friends on the phone, much of the time indulging in gossip and assorted banalities. His book on philosophy reflects his immersion in the banal, a kind of ritual he needed to partake in. He was much taken by kitsch and bad taste.

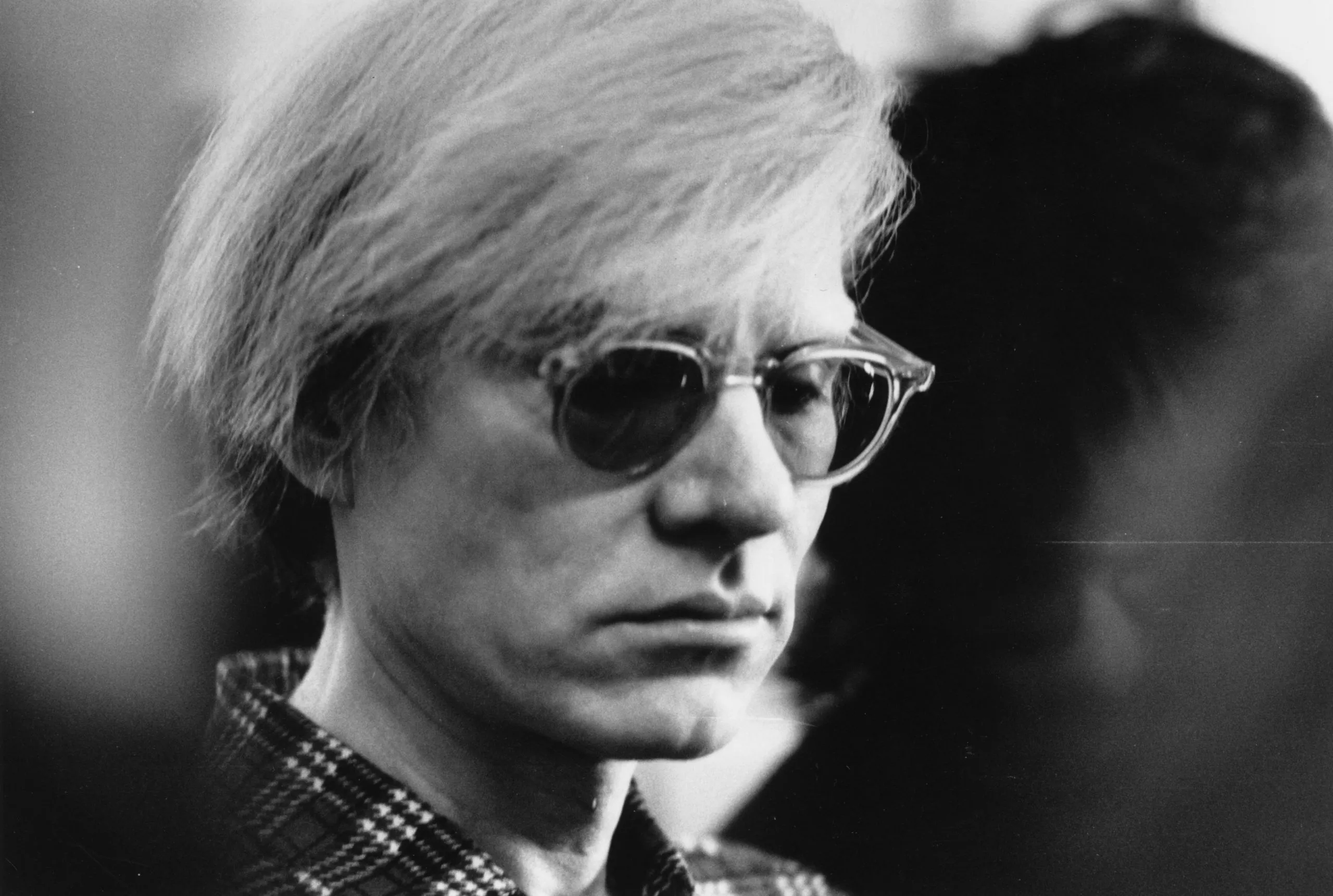

Andy Warhol in 1971. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Warhol was the outsider’s outsider, failing to fit in even with the rebels he was sympathetic to, such as Rauschenberg and Johns, whose ideology and style he could not agree with. His Czech immigrant roots ensured he would not oppose the ethos of Americanism, which he aspired to – he wanted to be American with an intensity only those excluded from it could want. Rauschenberg and Johns were critical of Americanism, especially the US involvement in Vietnam.

Warhol was obsessed with American celebrity, the ultimate sign of belonging. To be a celebrity meant being part of the unelected elect, the cultural elite who led lives in a sublime halo. Warhol was seduced by Hollywood, its stars occupying an empyrean region more hallowed than that of any other elite. He insinuated himself into the lives of Hollywood stars such as Liz Taylor and Liza Minelli.

Art critic Robert Hughes regarded Warhol as stupid because, he said, Warhol “had nothing to say”. But Warhol was not inclined to gnomic utterances, and his conversations were about gossip, sexual secrets, forbidden topics, all littered with wry observations.

David Bowie reported that when he met Warhol the artist was reticent, saying little. And when Bowie played his song Warhol to the artist Bowie wasn’t sure Warhol liked it. He couldn’t have: The lyrics are disparaging, mocking the artist as well as his art, with the lines:

“He’ll think about paint and he’ll think about glue/ What a jolly boring thing to do/ Andy Warhol looks a scream/ Hang him on my wall/ Andy Warhol, Silver Screen/ Can’t tell them apart at all.”

The uses of Superficiality

Warhol and the pop art movement changed the content of art works of the 1950s and 1960s. After the long reign of modernism, depicting abstract objects, pop art introduced new objects in art: The stuff of a world changing at breakneck speed from the dour colours of the first half of the 20th century to the proliferation of new commodities, of consumerism, of new forms of music and popular culture, of technicolour movies, cars. They also challenged the convention of painting, and Warhol’s silkscreens, serigraphs and other reproductive techniques made of painting just one among many forms of presentation.

Warhol’s artistic career began with Marilyn Monroe and cans of soup, Coca-Cola bottles, soap boxes, moving to car crashes and electric chairs, finally settling on Marilyn-like works depicting an endless stream of Hollywood and political celebrities in his final decade and a half. “More than anything, people want stars,” Warhol intoned.

A visitor to the Pop Art Portraits exhibition at National Portrait Gallery looks at Andy Warhol’s ‘Marilyn Monroe (Marilyn) 1967’ on October 10, 2007 in London. (Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

In the 1970s millionaires commissioned him to roll off their images on his silkscreens, and he produced portraits for a string of German businessmen. According to Fred Lawrence Guiles in Loner at the Ball, his biography of Warhol, the artist flew to Germany “where he executed more than 50 portraits” over 45 days, making $120,000 from each sitter, $4-million in six weeks.

He also painted arty types: Capturing Truman Capote, Roy Lichtenstein, David Hockney, Liza Minelli, Paloma Picasso and Mick Jagger.

Two gallery technicians adjust a painting by Andy Warhol entitled “Debbie Harry” in Sotheby’s auction house on June 17, 2011 in London, England. (Photo by Oli Scarff/Getty Images)

To modernise his country’s artistic culture, the Shah of Iran bought Warhol’s Suicide (Purple Jumping Man) for Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art, before commissioning him to silkscreen images of himself and his wife.

This was late capitalism in full bloom, and nothing embodied this better than Warhol’s Dollar Sign – simple presentations of the currency’s sign produced in the Raegan era – and his much earlier Dollar Bills series.

His Diamond Dust Shoes, part of a retrospective of his earlier interest, contained drawings of shoes overlaid with diamond dust to increase their value and glamour.

Culture theorist Frederick Jameson has compared the Diamond Dust Shoes (1980) series with Van Gogh’s rendition of peasant shoes. The former are the stuff of leisure, luxury and the fetishism of high culture, an exercise in pure commodification; the latter presents an organic relation to the earth, to food and sustenance and scarcity.

There were apparent exceptions: His Last Supper and his series Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century, among them Freud, Einstein, Kafka, Golda Meir and the Marx Brothers.

The prices paid for Warhol’s works are perhaps the last word, in a capitalist network, of opinion about his worth as an artist. It has been reported that he is the “highest priced” artist from the US.

One work with Basquiat, Zenith, sold for $11.4-million in 2014. A fat price indeed. But in the same year, Race Riot sold for a far fatter $63-million. Other works fetched even higher prices: Turquoise Marilyn sold for $80-million in 2008, Eight Elvises for a staggering $100-million in 2008; Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) went for a mere $105-million in 2013.

Such is the legacy of Andy Warhol. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.