FRIDAY ACTIVIST

Elma de Vries: ‘Do what your hands find to do’

Dr Elma de Vries is an activist in the public healthcare sector and among only a handful of health professionals championing the health needs of South Africa's trans community. Karin Schimke unpacks De Vries’ story.

When Elma de Vries was a very young doctor, she was idealistic and wanted to change the world. One day, feeling overwhelmed at her enormous caseload, she expressed her distress. Her boss at the time said something to her that has had a profound effect on how she lives privately and publicly, in work and in service.

“Elma,” he said, “just do what your hands find to do.”

She considers now that this way of approaching one’s work is what would, in modern terms, be labelled “mindfulness” — to stay within the moment one is in, instead of worrying about whether one is prepared for the moments ahead, or fretful about the ones just past.

Elma de Vries by the autumn-flowering small bush violet in her Mowbray, Cape Town garden. Her packed worked schedule, activism work and PhD studies mean that she takes downtime very seriously. ‘Green therapy’ – being in nature, hiking and bird watching – are the ways she unwinds from the never-ending grind of trying to provide dignified health care to people who face setbacks on every front in their daily lives. (Photo: Izak de Vries)

Another bit of advice came later and supported the first: a doctor sees many patients in one day, a supervisor told her, but for the patient, you are the only doctor they will see that day. Remembering this always brings De Vries back to the patient seated in front of her, waiting for help or guidance or medicine or just an ear. And that’s what she’s been doing for 27 years: serving patients in public hospitals and clinics.

Simply doing one’s job is not activism though. De Vries’s reputation as one of a tiny handful of go-to doctors for South Africa’s trans community is what elevates her dedication to equitable health for everyone from the prosaic to the inspired.

It has never occurred to De Vries to leave public health. She went into it wanting to help people, with what used to be known as “a calling” — a strong and persistent attraction to a helping profession. Speaking of a career as a calling most often has religious connotations, and De Vries grew up in a family for which callings defined lives: her ancestors were missionaries. Bittereinders. Diehards. People who did what they believed in, however hard the going was.

“As a white South African one has to reflect on your ancestors, and I’ve come to a place where I accept that they were children of their time and they worked with the worldview and insight that they had at that time. And my worldview is different; very different (to the idea they had) that the Christian Western perspective is the better one.”

Some years ago, Elma de Vries retraced her missionary grandmother’s footsteps as she arrived in Africa and set out for Beira. She feels it is important to reckon with your ancestors, who they were and what they did. As she sat on some boulders by Lake Malawi, she imagined her family’s past as a woven cloth streaming behind her. The further back the cloth was, the more monotone it was, but as the cloth came closer it brightened until, in her hands, it was all the colours of the rainbow. De Vries is now one of South Africa’s foremost medical activists in the area of LGBTQI+ health matters. And she wears her cloth of many colours with pride. (Photo: Izak de Vries)

She certainly identifies with the stubbornness of her forebears though. Toughing out difficult conditions to do what you believe is right is part of her genetic make-up, she says.

De Vries’s father was a dominee in the NG Sending Kerk in Riebeek West, the missionary arm of the Dutch Reformed Church. She herself has never stopped reading theology, or going to church, although the church she belongs to is radically different to the one she came from. Her mother was a nurse, and a deeply caring human being, according to De Vries, who is the eldest of the couple’s three girls. Caring and community were integral to De Vries family life.

Standing on the brink of adulthood, it was medicine, though, and not theology, De Vries chose to pursue, and her calling has given her 27 years of experience in the public health sector.

Did she ever consider going into private healthcare?

Never, she says, just as a rescue helicopter thumps noisily over the Mowbray garden where two socially distanced camping chairs have been set up beside a merrily flowering small bush violet, whose purple blossoms shiver in a chilly wind. She watches the helicopter pass and when the noise has retreated, she adds “And anyway, I’m bad at business.”

Bad at business is often very good for other things. Which brings our conversation around to how De Vries came to be one of South Africa’s foremost trans activists.

De Vries is a senior family physician at the Heideveld Community Day Centre in Cape Town and was appointed by Cape Town Metro Health Services to set up the Mitchells Plain Covid-19 field hospital, which she and a team managed to have up and running within two weeks during the second wave of the pandemic in December.

Besides her day job as an employee of the Department of Health, she teaches as a senior lecturer in the Division of Family Medicine at the University of Cape Town and is doing a PhD in Health Science Education.

Her legacy, however, is likely to be her work at the forefront of transforming medical health responses to people who seldom have anyone fighting in their corner: the trans community. She has been a trainer for gender-affirming healthcare with the non-profit organisation Gender DynamiX, as well as serving on its board, and was part of the Groote Schuur Hospital Transgender clinic team that lobbied the National Department of Health to have gender-affirming hormone treatment included in the Essential Medicines List, something that was achieved in December 2019.

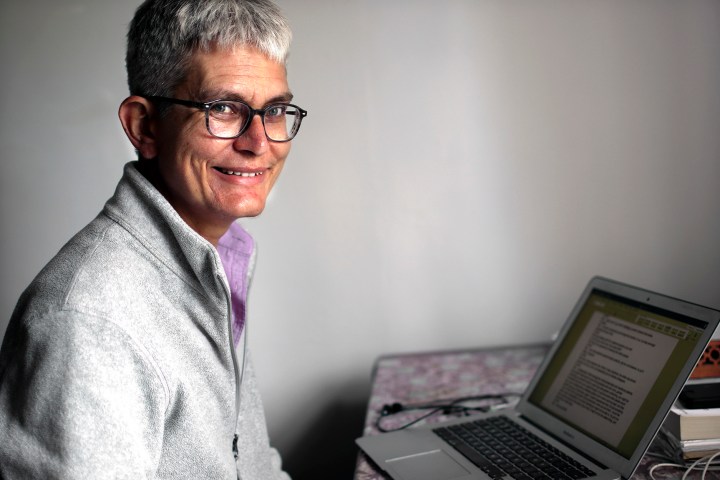

Elma de Vries is a family doctor in Mitchells Plain, Cape Town, and uses her spare time to address lacunas in the health system when it comes to the care of the queer, and especially the trans community. (Photo: Izak de Vries)

She is a founding member and secretary for the board of the Professional Association for Transgender Health in South Africa (PATHSA) as well as a member of the World Organisation of Family Doctors’ Special Interest Group on LGBT Health.

She is also one of two original co-authors of the first South African medical guidelines for caring for trans people at all levels of health services in South Africa, published by Gender DynamiX in 2013, and is part of a team currently developing national guidelines for gender-affirming care, coordinated by the HIV Clinicians Society.

It was through her church, and not through her work as a public family doctor that De Vries came to be in service of the health needs of the trans community. She attends Good Hope MCC, a Christian church that states love is its “greatest moral value” and that “resisting exclusion is a primary focus of our ministry”. This international church isn’t just welcoming of LGBTQ+ folks — diversity is built into its very structures.

“My entry into the transgender advocacy world was actually not with a patient but at church. The person who started Gender DynamiX, Liesl Theron, was in my church, and did a workshop on transgender health there.”

The workshop was a “wow moment” for De Vries who was struck at the time that none of what she was learning had been taught to her at medical school, “and yet here were human beings with medical needs that weren’t being met”. She needed to learn more, she said, and became involved with Gender DynamiX.

“Then I made a good friend at church who thought she was gay, though that had never felt quite right, and through watching a video we had in the church library, she realised ‘this is it! this is who I am!’. So I had the privilege of walking alongside a friend on their journey of expressing who they really are.”

But being one of a handful of doctors interested in the health needs of the trans community doesn’t necessarily make one a hero in everyone’s eyes. Trans people around the world have had bad experiences with health professionals, interactions that range from dismissive all the way through to outright abuse. The result has been deep negativity towards and lack of trust in health professionals.

Elma de Vries is a voracious reader and particularly enjoys reading modern theology. She and her husband live in a home where the walls are lined with bookshelves. (Photo: Izak de Vries)

Twenty-seven years in public health in South Africa will teach anyone patience, time management, effective listening, and how to hold on to a sense of humour. Certainly, these qualities are evident in the way De Vries interacts. Her mode of engagement is contemplative. She listens to questions quietly and doesn’t rush to answer. Her responses are always fluid when they come — like someone who knows what they think but is always willing to stop and reconsider.

When she is asked whether she thinks of herself as an activist, the question elicits a long and hearty laugh. One gets the sense that this is something she has pondered before anyone thought to ask the question. Why is she laughing, I ask?

“Because the fascinating thing is, I learnt about different ways of being also at church. We did a workshop on spiritual styles and it became clear that, even in church circles, there is an ‘activist style’.

“The activist style wants everybody to think like them, and to be an activist like them, and they are almost a little bit fundamentalist in the way they look at things. And people who have a more contemplative spiritual style, where things are more of a mystery and not as clear-cut, are sometimes judged by the activist-style people. I’ve experienced that.

“Some activists are so passionate about their cause that it’s easy to be judgmental of other people who don’t see things exactly the way they do. That is not true for all activists, though. There are activists who understand intersectionality and that so many injustices are interlinked. People have written about how it is necessary to have a more nuanced approach, but that might be difficult if it feels to you like you’re on the frontline fighting an unjust world.

“So, to answer the question about whether I’m an activist, I suppose it depends on how one defines activist. But yes, I see myself as an activist. Some radical activists may not regard me as the same as them, but in my field of influence I try to make the world a more friendly place.”

De Vries hasn’t only recently been trying to use her field of influence to make the world a friendlier place. She’s been doing it since her early days when she worked at Tshilidzini Hospital in Thohoyandou and became involved with the Rural Doctors Association, which advocated for better health provision for people who don’t live near major urban centres where health provision is more reliable. It was during this time that De Vries says she “found [her] tribe”.

“And my tribe is people who care and who want to make a difference.”

It has taken months to get the interview with De Vries and it only happens right at the very beginning of a short sabbatical during which she will be working on her PhD, which brings together all three of her roles as doctor, medical educator and LGBTQ+ activist, and the research of which will inform future generations’ engagement with the topic. She is a woman one would imagine is run off her feet, and yet she always seems calm. This is despite the fact that “there are moments when you look into the deep, black hole of desperation and you can’t imagine how people survive”.

She has an infinite number of stories of people whose struggle with health is only one of several, their lives a complex web of social, political, personal and interpersonal strife — in a country where an unimaginable struggle goes on daily, especially since Covid and its concomitant job losses, food insecurity and the innumerable stresses it has visited on people who were already under severe strain.

It distresses her, as it has most South Africans, to see how resources have been squandered in recent years due to corruption, but the anger it elicits fuels her determination to continue striving for equality in healthcare for all people.

“The woman who comes to my clinic with diabetes, who has a son in prison and a daughter on drugs deserves exactly the same healthcare as the woman in Constantia who lives in a mansion and doesn’t need to work. By all people, I mean all people. All includes everyone. Even cisgender, white men.”

She doesn’t let the abyss of darkness and desperation claim her, no matter how hard she works or how few hours there are in a day. She uses “green therapy” — hiking in nature, birdwatching — and reading to find equilibrium. She clearly regularly counts her blessings, which include a husband who not only shares the running of the household and family equally but steps in without complaint when her paid hours at work spill over into family time. She also has independent and supportive children, good relationships with her extended family, and “a job and a sense of purpose”.

To be overwhelmed, even during South Africa’s brutal second wave, just doesn’t seem to be an option De Vries entertains.

“One realises the limitations [of being a public health doctor]; that there’s only so much you can do. And sometimes that ‘so much’ can really make a difference. And that can also be satisfying. Even if it’s never entirely enough.” DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A giant of humanity who has the kind of reflexivity which few others delve into – our personal prejudices about so many issues ! Looking at some of the blase (unconsidered or not thought through) comments some correspondents post, this is the kind of contemplative individual we need more of.