MIND MATTER

Nation on the Couch: The things we don’t want to know

In a country saturated with social commentary, a new book offers an unusual perspective on our nation’s apparent madness and its various expressions and suggests that we share a political unconscious that it’s probably going to be hard for us to face up to.

South Africans share a political unconscious and until we stop to consider its destructive influence on our daily lives, we’re likely to continue bumbling violently along on our shared path towards some murky and worrying destination.

Our collective anxiety is high, whether we’re standing on the street corner hoping for piece work or taking our Rottweiler along on the leash when we go for a run.

Does psychology have anything to offer us to mediate this anxiety?

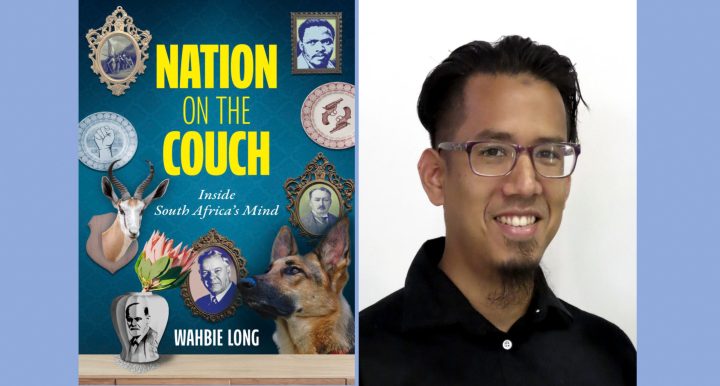

Wahbie Long, clinical psychologist and associate professor of psychology at the University of Cape Town, believes it does, as long as the discipline of psychology can make room for more than just individuals’ responses to the material circumstances of our social context.

Long, who is considered one of South Africa’s brightest academic minds and has received various honours, points out that sociology and social commentary ask and find answers for questions like why we “lurch from one social crisis to the next”, why we “brutalise each other, both interpersonally and structurally” and why we seem “condemned to repeat the wrongs of our harrowing past”, outlining all the governmental, structural problems in South African society.

Psychology, on the other hand, he says, tends to – if it considers politics at all – reduce the social to the psychological, forcing individuals to bear the weight of everything that ails them, without considering the social structures that shape them.

Long wishes to bring the sociological and the psychological view of the country closer to one another and for us to find new ways of thinking about ourselves and our relationships to one another. Because, he says, “unless and until we apprehend the monsters of our collective deep, the compulsion to repeat will not be going anywhere anytime soon”.

It’s a radical idea to put an entire group of people, particularly one as disparate and outlandishly removed from one another socially as South Africans are, on the proverbial therapy couch, as though the nation is a patient wanting to feel better, and yet Long manages this exercise convincingly, pointing to the needs and complexes that underlie the emotions that present – and often cause havoc – in our daily lives.

Nation on the Couch is hard reading at times. Hard the way that therapy is said to be hard. There are truths here people will not want to hear, much less break their head thinking about how to fix them. Long’s rigorous research, lucid arguments and accessible writing cut right through the lies we tell ourselves all the time and one is put in mind of the saying, which borrows from the title of a book by the feminist Gloria Steinem, that says “the truth will set you free, but first it will piss you off”.

Psychological language has become routinised. It’s as though there’s no other way to talk about our experiences other than through the language given to us by psychology.

To understand Long’s proposition requires the reader to understand a little about the unconscious mind, which he explains in the introduction.

Most of us believe our behaviour is controlled by our thoughts. We decide on a course of action and follow it. It’s all rational, we believe. We have a certain amount of power – some of us have more of it than others do, but we all have it, we believe – over ourselves and our decisions, and we choose to exercise that power by making logical calculations.

Psychology, however, indicates that we are not driven only by what we know. There are forces at work in us that push us in certain directions, make us avoid certain courses of action that would be beneficial to us, and which make us retreat from certain types of people or activities.

This is known in psychology as the unconscious, which is formed from beliefs and biases we aren’t even aware we have. It is that part of our mind which is below the surface of our understanding of ourselves.

Long extends this well-documented concept to propose that we also have a political unconscious. The things we label “senseless” in South Africa (violence, destroying university property, the greedy accumulation of assets via corrupt methods) are in fact, seen from a psychological perspective, not senseless at all.

But to understand them we need to bring them into the light, because, to quote writer James Baldwin, “not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced”.

Maverick Citizen spoke to Long about Nation on the Couch in more detail.

Were there any new insights for you as you were writing Nation on the Couch?

I’ve had these thoughts and hypotheses for some time, and I don’t see it as me discovering something unique. I get the sense that a lot of what’s in the book is stuff that people have actually been feeling in quite an indistinct way and for which, perhaps, there hasn’t been a language. Maybe this book gives those unformed thoughts a language, gives us a way to articulate things.

The impact of the book on me personally, though, was more the question of hope. That’s the part that I’ve really sat with. What does this book mean in terms of the future of this country? And you’ll know that the public discourse is saturated with that discourse: Where are we going? Are we going to survive? And writing this book I was able to answer that question for myself: Whether there is hope for South Africa.

I do think that by raising the possibility of a political unconscious you’ve given us new language for framing what ails us, one that connects the field of psychology with the field of sociology in a way it hasn’t been in the public domain. It’s good to have a common language for things that have been dismissed before, but psychological terminology is rife in public language right now, especially on social media, and I wonder sometimes whether the wrong use or overuse of certain words means that the very tool we need for understanding one another is being blunted.

The psychologisation of modern society, especially in the Anglophone world, has been going on since the Reagan and Thatcher years, and everything gets seen in psychological terms now. The same trite stuff comes up over and over again. Psychological language has become routinised. It’s as though there’s no other way to talk about our experiences other than through the language given to us by psychology.

The danger is that the work then might not get done. We label something and stop there.

The power of naming is not to be underestimated. To have an aspect of your experience named in a way that resonates with you is a powerful experience. That’s just the start, but that’s not where the work of therapy ends. One must not fall into a performance of the therapeutic language. There’s a difference in performing therapeutic language and actually using it to illuminate things and to change how you are in the world.

Is there such a thing as national identity? Does South Africa have one?

It’s the national question, right? Is there a South African nation, given how fractured this country is? And the very nature of the book points to that fracturing. Linguistically, when we talk about the nation, we imply that there is a whole nation to speak of. Yet, as one moves through the chapters, readers will get a sense that there are fissures in our nature and different constituencies are grappling with different questions.

I’m at pains to explain in the book that alienation is a bridging device that colours not just our internal worlds but our external worlds as well.

The chapter on shame, for example, is about the poor and working classes and the problem of violence, particularly interpersonal violence. The word violence gets used in very generic ways these days – symbolic, structural, interpersonal, gender-based – but that chapter looks at violence on an interpersonal level, inclusive of gender-based violence.

The chapter on envy looks at the rising black middle class and the question of inequality and perhaps, I suppose, symbolic violence. And the chapter on impasse looks at white South Africans and the question of ambivalence around, for instance, racial integration.

So there are deep fractures and the structure of the book attests to that. But in the same breath, there is something that unites us and for me it is the problem of alienation, which is not just a psychological condition.

The word “alienation” most often gets used as a feeling state. “I feel alienated from my spouse, or from my work, or my university. I feel alienated.” But I’m at pains to explain in the book that alienation is a bridging device that colours not just our internal worlds but our external worlds as well. And the condition of alienation, as opposed to the feeling of alienation is what affirms the unity of South Africa in quite a paradoxical way. We’re a nation because of our alienation. That’s what we have in common.

Is the easiest way to understand alienation “a relation of relationlessness”?

Exactly. When people use the word alienation colloquially, they typically mean “I don’t have a relation with something. I’m cut off from it. I’m estranged. I’m separated from it.” But that’s not how I understand alienation. I go with the definition of “a relation of relationlessness”. In other words, you have this relation with the external world or with yourself, but it’s characterised by relationlessness. In other words, it’s a completely distorted relation. It’s not an un-relation. It’s about a distorted form of relating to the external world and to oneself.

Would lack of reciprocity be a part of that distortion?

Certainly, that’s part of it: The question of recognition. When you are systematically and repeatedly disrespected and misrecognised by someone, then that relationship is distorted. Alienation is then built into that relationship.

The book is groundbreaking in terms of giving us as lay people a language for discussing what ails us, but it’s almost perverse in its directness.

On that point, I was actually thinking to myself recently, I wonder whether this book will become academics’ dirty little secret. Because it is a controversial book. Obviously. And I have this feeling that people are going to read it, but they won’t tell each other that they read it. They might think “this is really important for me”, but they might not necessarily want to talk to other people about what they thought of the idea of envy and fallism, or shame and violence.

I almost feel like some of the links drawn in these chapters might be a bit too much right now to be part of public conversation, and there might be a lot of missteps before we get there.

What is the most controversial thing you say in this book?

It depends on who the audience is. I think white people will be pissed that I suggest that they use dogs as a form of compensation. I think it would be upsetting for them. Some might snigger to themselves and take it in a playful spirit, and in fact some of my white students have said “guilty as charged, that’s me” and they’ve taken pictures of dogs off their WhatsApp profiles.

In the chapter of shame and violence, what worries me is I don’t know how many poor and working-class people would be in a position to spend money on a book like this, so I’m not sure how valuable the insights might prove in the life of the nation. Maybe it’s useful for affluent South Africans to know what drives interpersonal violence.

I’d say that to talk about envy, even in a Kleinian sense, and link that to fallism and the whole decolonial move, is pretty controversial. There are different points of controversy for different audiences, but I would say that for me as the writer, it is the connection I draw between envy and fallism and decoloniality.

My working life is based at a university, so obviously I’m going to be wondering, how are my colleagues and peers going to take this. Is it going to be met with a deafening silence, will there be an attempt to engage, will there be ad hominem attacks? I guess we’ll find out once a critical mass of people have read the book.

This is the question of our age though, isn’t it? I was very surprised, for instance, that you quoted from Disgrace, by JM Coetzee, the book that everybody loves to hate. Public discourse is generally avoidant. It hedges. It’s careful to the point of paralysis. So I’m really interested in finding out what the psychology is of going where others might fear to tread.

That’s a great question and it is one that I’ve thought about. I think that growing up in predominantly white schools in the early post-apartheid years left me with an acute sense of being on the outside. And what that meant, psychologically speaking, is that I spent a lot of time observing and I’ve got little doubt that it influenced my decision, at quite an unconscious level at the time, to become a psychologist, because that’s what psychologists do: We watch. We’re professional watchers.

When people hear about the outsider, they typically think “ag shame”, but my relationship with my outsiderness is something I’ve come to embrace. It’s what allows me to write and think and say the things I do. Because I don’t have a tribe, I’m not beholden. I’m able to think my own thoughts and not have to worry about who’s going to come for me. I can honestly say that “this is what I think, here are my thoughts”. I’m comfortable with being an outsider, essentially. I don’t feel, I suppose, the trepidation that other people might feel.

I could very easily face criticisms that I’m heavily dependent on dead white men and that therefore the entire argument falls flat.

But there’s another aspect to this. The word “courageous” has been used to describe not just this book, but much of my work over the past five or six years. I’ve wondered about this word and why people use it. Perhaps they think it’s courageous because they would never put their head on a block and say the things I’ve said, but I do worry about the characterisation of my work as courageous, because of what that says about the academy. What does it mean about our intellectual culture that if someone is just honest in the expression of their views, just honest, then it’s courageous?

I could write this book also because I was the recipient of a fellowship that allowed me to go overseas and escape the thought policing that has taken over large swathes of public interaction, not just in South Africa, but all over, and there is a culture of intimidation within the academy. When intellectuals are no longer able to say what they truly think, what is the intellectual project? Then it’s not worth the name. There is too much posturing and too much pandering.

But simply stating what you’re stating almost puts you in a grouping with the kinds of intellectuals who seem to be falling out of favour. The philosopher Peter Singer, for instance, who adheres to a private philosophy of “the greatest good for the greatest number of people”, which means that he gives away most of what he earns, said in a New Yorker interview recently that he and a few other academics are going to start a journal with rigorous peer-review systems built in, but in which they will allow academics and thinkers to anonymously publish ideas considered…

Heretical?

Yes.

What then is all the other stuff we’re writing? That we put our names to?

Is that the way to go, though? To not put your name to your idea because you’re afraid you’ll lose your job? One is struck by the fact that you make your observations in this book within the context of Western forms and expressions of knowledge and that in itself might render the whole project invalid in the eyes of some. Were you aware of that irony, and of the Catch 22 of this?

You mean in the sense that I’m quoting from the Western canon to build my argument? Ja. Obviously. I could very easily face criticisms that I’m heavily dependent on dead white men and that therefore the entire argument falls flat.

I face this situation with my postgrad students. I teach a course on philosophical and theoretical issues in psychology and what I’ve noticed in the past few years is that, for instance, I ask students to do book reviews, where they have to read a book on the history or the philosophy of psychology and they must present it to the class. I’ve noticed a trend where, when they sum up the review, they will say something along the lines of “we need to remember that the author is a white man from Europe and therefore his book is not relevant for South Africa”.

I take it upon myself to call students out on that. I tell them that that is not a critique. That’s just intellectual laziness. You’re not engaging with the contents of the book, you’re simply writing it off, based on the author’s demographic markers. But that’s what’s happening in the academy these days and it is dressed up as scholarship – that your identity markers will determine the value of your academic work. And it’s a tragedy.

I’m just in psychology, but if one moves between departments in the humanities, students speak the same language, and that comes back to the point of triteness of language over time. The race-sex-gender trinity is the only language students talk these days, regardless of what discipline they’re in.

Now when there’s only one language in town, regardless of the discipline, that’s a problem, because it suggests that there is a toolbox, there is one hammer in that toolbox and, by God, every problem in the humanities is going to be a nail – whether it is one or not – and we’re going to use our hammer.

The point you make about academics wanting to set up an anonymous journal. Yes, people might lose their jobs, but it’s difficult to lose your job in the academy unless you go out of your way. It’s hard to get fired. You might have a problem getting promoted for saying things that are not in keeping with the party line, as it were, but it’s hard to get fired. So I think that academics, particularly senior academics, don’t really have an excuse when they worry about intimidation or what the reaction might be to them expressing their thoughts on a matter.

You talk about the dangers of moral absolutism in your book. You also remind us, as we know from so much other learning, that we are not rational beings. That is comforting, particularly in situations where it feels as though interpersonal trust has been apparently irrationally overturned. We’ve all had the experience where you are interacting with someone in what feels like a situation of mutual confidence and suddenly things just go pear shaped, and you have no idea why. It’s comforting to think that something unconscious has been stirred which is why something irrational has happened, either on the other person’s side or on your side, and which you just can’t see clearly. But it still causes institutions and individuals huge damage. How does one come back from situations where the unconscious, whether personal or political, has arisen and is biting us?

I think that the general public doesn’t believe in the idea of an unconscious, because if we accept that there is such a thing as an unconscious and that we are largely irrational beings and that there is a lot going on outside our conscious awareness… to be convinced of that is a very humbling thought. The idea that I don’t know it all, that I have a very partial view of the situation… that’s hard. There’s been so much moral absolutism going on, at least in higher education, where people really seem to think that what they believe in is the whole picture.

I remember giving a seminar based on this book, before it was a book, at the University of the Witwatersrand, and one of the professors said, “I simply don’t believe that there’s something at the back of my head that I don’t know about”, and was quite clear that as far as he was concerned, he is 100% rational and always fully in control. Any psycho-dynamic therapist would have serious reservations about that. The understanding for psycho-dynamic therapists is that most of our mind is underwater.

The idea of an unconscious – a political unconscious in particular – would just make us, I believe, interpersonally a bit more hesitant, a bit humbler and a bit more curious, actually, about ourselves and about other people, as opposed to simply assuming things.

So the moral and social value of an idea like the political unconscious is substantial.

You speak in the book about “yielding, rather than asserting yourself aggressively”. One sees behaviour all around in public life that shows an absolute conviction that your experience of life is the only valid one. Asking people to “yield” seems like such an impossible thing to expect. It evokes the image of a dog rolling on its back to show submission. How does one yield, as an individual or as a group, without feeling like you are giving up your sense of self, without exposing your vulnerable underbelly, without sublimating, suppressing or minimising your Self.

The question of yielding is difficult for all people, not just white people, but also for black people. The underbelly is usually stuff we don’t want to show anyone and don’t want to admit to ourselves. You can only yield when you know the other person, when you are exposing yourself to someone you can trust. Someone who is not going to wound you even further. And so what yielding requires is a capacity to imagine that the person that you are with can hold you in your vulnerability. And how hard that is in a country like ours, especially across racial lines. It certainly is asking a lot.

We are talking about psychological trust and that is hard to build, especially here, but one of the lines I push in the book is that when it comes to hope, there are two things: Psychological hope and material hope, and we can’t pursue one at the expense of the other. That is why I think that if South Africans can, on a material level, treat each other better, then it makes the possibility of psychological yielding a little less fraught.

When our real attempts at connection and understanding are rebuffed, sometimes in ways that are hard to swallow, then more is required of us. In the book, you say that we need to give respect and recognition to one another. These are active things we must do. But sometimes we are the recipients of lack of respect and of misrecognition. When we receive behaviour like that, things that really go to the core of who you are as a being, our instinct is to hit back or to retreat. What you are saying in your final chapter is, I believe, that where a relationship is established, or re-established or affirmed or grounded again, is in coming back and coming back and coming back, in spite of these missteps. Is that correct?

Yes. Both parties have to keep in mind the overriding goal, and the overriding goal is to find each other. To create these moments of meeting, but also to know that people don’t stay the same forever. Just because you found someone, doesn’t mean that you’ve found them forever. They’re going to change, they will be upset again, they’ll be difficult with you, and then the process has to start up all over again.

That’s why in analysis we talk about “working through”. One has to knock one’s head over and over and over again. It requires a willingness to go through with the process.

I think also about the distinction analysts draw between what they call “the will to be healed” and “the will to be analysed”. If the only thing that the patient (or a nation) wants is to get better, they’re going to find therapy frustrating and disillusioning, terminate and never return. The will to get better just isn’t going to cut it. But the will to be analysed means that you’re curious about yourself. You want to figure yourself out. And if you have that, you are much likelier to stick to the therapeutic relationship. All the disappointments and frustrations are still going to land, but because there’s this underlying desire to know yourself, you’re not going to run for the hills as easily. And if we transfer that idea to the national situation, sure, ultimately, we want a good relationship with one another, we want to feel better about ourselves, be able to build friendships with people of various backgrounds. But the basic ingredient to get there is to be curious about ourselves, to be curious about our internal life as a nation, because without that, we’re not going to persist.

If we can believe in the idea that there is stuff that we don’t know about ourselves, but we’re interested to explore them – if I am curious about what I don’t know about myself and my nation and the political unconscious – if there can be buy-in to that idea, then there’s real potential for building these moments of meeting for each other.

There are people who want to live an examined life, whereas others really prefer to just get on with their lives. Why do we have to think about this difficult stuff? Shouldn’t the government just be sorting it out by doing its job properly?

Just as there are defences that prevent us from engaging with the personal unconscious, so too there would be defences of engaging with the idea of a political unconscious and people will come up with all sorts of reasons that they don’t want to do that work. It’s not only a defensive response, but also an understandable one. But there’s a lot at stake here.

One of the phrases I used several times in the book is repetition compulsion. We do the same stuff. We brutalise each other over and over and over again, in all sorts of ways. And not just interpersonally, but also structurally and symbolically. If we want that stuff to stop, we’ve got to understand what’s going on.

There is also a mythology we’ve created about ourselves that we’re so tough. We live with crime and violence, sometimes we have no water, often we have no electricity, but the fearlessness that is required for us to proceed with the understanding of ourselves you wish us to have is not that same sort of fearlessness. It’s not living with the fear of homelessness or hunger or violence. A different kind of fearlessness is required to face the political unconscious.

Maybe not fearlessness. Maybe this is a situation where it isn’t fearlessness that is called for, but courage. I think now of that quote from Nelson Mandela where he speaks about courage not being the absence of fear. Persisting through the fear is courage.

There must be fear in a therapeutic situation. Because the prospect of knowing another human being – it’s not just elusive, it’s frightening. Showing up is not about fearlessness. It’s about courage and pushing through despite the fear.

We South Africans want answers about our future. It seems to me that what readers in this country are reaching for in their appetite for non-fiction books with titles like How long will South Africa survive?, We have now begun our descent – How to stop South Africa losing its way and What if there were no Whites in South Africa? is hope that all is not lost. And that is where you end up with the book. You have this very complex academic problem that you research and work out and put down on the page to share with your readers in a way that they can understand it. And then in the end, what you come to is…

Common sense?

Yes. And something that’s even a bit touchy-feely. And in a post-theist world it is interesting to me that the answer has been there all along. Are you aware of that weirdness?

The concluding chapter on The Golden Rule was the hardest chapter for me to write. I’d gone through diagnosis: Shame, envy, impasse. Then I went to prognosis, which was hope, saying that it exists, but certain things need to happen. But then where’s the treatment plan? You can’t just have diagnosis and prognosis. You have to have a treatment plan, too.

And the treatment plan is The Golden Rule. Yes. It’s a very simple formula, but it’s also the one thing that human beings, across time, across place, have come upon as a rule for living. And granted, it sounds like psychobabble: Do unto others as you’d like them to do unto you, and do not do unto others as you would not like them do unto you. But that principle is about action. It can’t come alive in the mind only. Sure, you can hold it in mind, but it doesn’t count for much if it doesn’t find concrete expression in the way we live our lives.

It calls on us to live in a very particular way. And ja, sometimes the most profound things really are just the simplest things.

Mohammed said it. Jesus said it. Buddha said it. And yet we still fail at it all the time.

My response to that would be it’s a work in progress. We keep trying. And trying and trying. And we recognise that we’re not just living for this generation, but for the generations to come. DM/MC

Nation on the Couch is published by Melinda Ferguson Books, an imprint of NB Publishers.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This entire effort falls flat with a lame conclusion about the Golden Rule. Do unto others… cannot possibly apply anywhere and has been discredited so many times as unvalid by many academicians and philosophers alike. I am stunned that Long does not know this.

Adherence to the golden rule is a work in progress. It can be nothing else as we are, each one of us, works in progress not finished objects.

Ja I agree. The Golden Rule can be a bit lame, but it’s a work in progress. One of the criticisms of it is that it ignores that other people have different needs and wants to us, so we can’t assume that what works for us will work for them. But in terms of the practice of empathy, it’s still a powerful concept and also the only universal one for empathy that we have.

There are plenty of academicians and philosophers who just don’t get it. So gaan dit.

The reality is that every one of has arrived at the place that we are at through a multiplicity of circumstances and from an evolutionary perspective what we do next is what matters, not quibbling over the past. Is it life affirming or life denying, that is all.

Excellent interview and review. I found Wahbie’s book hopeful and profoundly thought-provoking (if a little too academic at times).