DM168 DEEP DIVE

What’s wrong with us? Inside the mind of South Africans

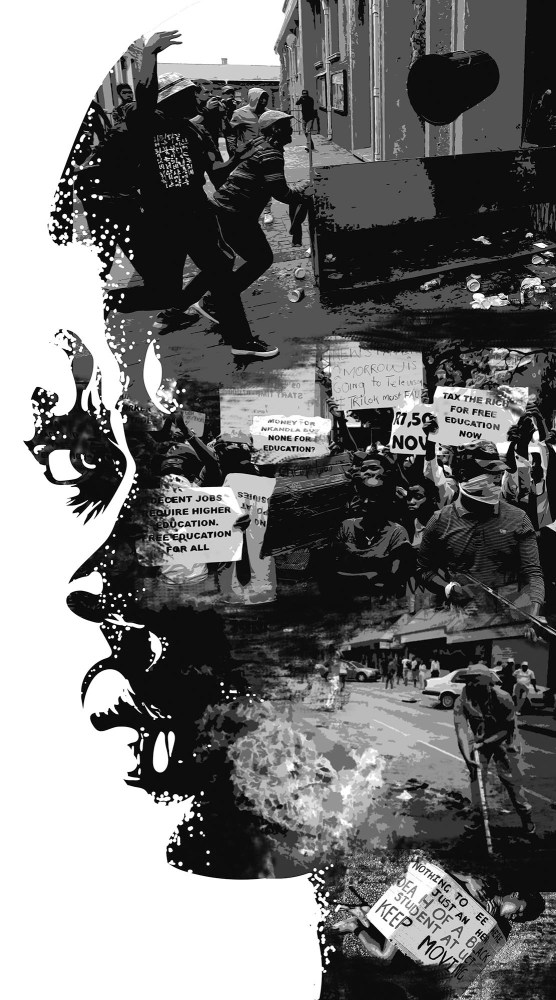

The widespread violence in our society is rooted in a deep sense of alienation and has left psychological wounds among South Africans, writes a local academic. Shame and envy are also painful elements of the nation’s wounded soul.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

Diagnosis: severe trauma and alienation. Remedy: build a bridge to the outside world and others.

The waves of violence that South African society has been exposed to over hundreds of years has left deep collective psychological wounds, which must be considered in any attempt to understand what is often termed the “senseless violence” that so dominates contemporary life.

“There is nothing senseless about the violence that occurs here,” says Associate Professor Wahbie Long, academic, psychologist and author of the just-published, provocative study, Nation on the Couch: Inside South Africa’s Mind (Melinda Ferguson Books).

Wahbie asks how 58 million souls can share anything approaching a shared psychic life in South Africa, especially considering that at the heart of the waves of cyclical violence that have washed over us is a deep sense of alienation.

From the 30-odd “service delivery” protests that take place in South Africa each day to violent student protests and grotesque levels of interpersonal violence, we are a nation estranged from ourselves and each other.

“Whether in relation to the state, communities, institutions, working environments, families, spouses — even one’s sense of self — it appeared to me that South African protesters were raging against an abiding disconnect between internal desire and external reality,” writes Long.

The external reality of protest is pervasive. Claims related to protests for the 2018/19 financial year were R1.7-billion, notes Long, more than double the figure of R800-million claimed during the previous year.

We are slashing and burning as we attempt to become something new, something other than what we have been. But alienation gets in the way.

And yet, notes Long, alienation should be viewed not as a mental state, but rather as a “bridging concept”.

After taking up a position as director of the Child Guidance Clinic at the University of Cape Town in 2017, Long says he witnessed “a cocktail of trauma, deprivation and destructiveness in the lives of many individual patients” who passed through its portals.

But Long also began to encounter problems that seemed different.

The more he listened, the more he came to understand that “nested” symptoms of dysfunction played an enormous role in the mental health of South Africans, particularly black South Africans, the working class and the poor.

These were factors located outside the mind of the client while psychologists and psychology, argues Long, have long continued to “treat patients as agents responsible for living their own lives”.

Long also witnessed, between 2015 and 2017, the convulsive and violent protests at university campuses throughout South Africa. However, he remarks that “the faces of student protests” did not fall into the usual category.

“They belonged to a new generation of so-called born-frees who were fortunate enough to have made it into elite institutions of higher learning.”

And it is here that history and its burdens of shame, envy and impasse combine into a toxic stew, according to Long.

Long sees himself as part of a new generation of South African psychologists who are less idealistic and philosophical about the discipline that has come to privilege individual desire “at the cost of social order”.

With Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx, Frantz Fanon and Erich Fromm as intellectual touchstones, Long has — with clinical precision — fleshed out “the concept of alienation apropos of South African life from late 2016 onwards”.

Alienation in South Africa, says Long, is overlaid with toxic racial calculus, which assumes virulent forms. Its root is a life-and-death struggle for recognition.

“Day by day we read headlines about violence and corruption, but these are only descriptions. They do not explain why we lurch from one crisis to another,” the author said.

Long uses three lenses through which to try to unravel the battered and bruised mind and soul of South Africa: shame, envy and impasse.

None of the terms are used in the colloquial sense, however.

Shame is at the root of much violence and substance abuse, envy is what happens when shame turns to resentment, and then there is “impasse”, which, particularly with regard to white South Africans, results in a withdrawal from communal life.

With regard to protests at universities, Long states that “a conscientisation about the workings of symbolic violence” is what lies at the heart.

It is about institutional culture(s) that has(have) made it “impossible for black students and academics to participate as their white counterparts’ equals in intellectual life”.

“Unable to challenge the system from the inside, the protest strategy is to disrupt business as usual by making the universities ‘ungovernable’,” writes Long.

Black student protesters were “no longer taking it upon themselves to interpret the world for the benefit of white people”.

The psychological import of Fanon’s verdict cannot be overestimated because it raises the crucial question of why — in the minds of student protesters — the pursuit of whiteness is transformed instead into its denigration.

“This may explain, in part, why black consciousness — a psychological project by black people, for black people — has re-entered the academic conversation after a lengthy hiatus,” says Long.

Longs asks the reader to recall Fanon’s “reluctant admission in the opening pages of Black Skin, White Masks — that the only real destiny for black people is the colour white”.

“The psychological import of Fanon’s verdict cannot be overestimated because it raises the crucial question of why — in the minds of student protesters — the pursuit of whiteness is transformed instead into its denigration,” says Long.

It is Freudian theory, however, that offers “the most elegant solution – namely, the reaction formation”, which, as per Fanon, “begins with the black subject’s desire to be white”.

“There is no fear of whiteness per se — but there is an overwhelming fear of the desire for whiteness. It is no longer the black subject but the white subject who becomes ‘a phobogenic object, a stimulus to anxiety’.”

The author writes, when fallists exclaim “We can’t breathe!”, it reveals this as “a classic symptom of a panic attack — whiteness having now been converted into a phobia”.

Although political commentators might suggest that fallist fury contained a touch of drama and students did “protest too much”, the “implacability” of anger had a compulsive feel to it, which is “another characteristic of the reaction formation”.

“For no matter how far backwards university management bent, students never seemed to be satisfied. It was as if they had to be angry — regardless of the actual deal on the negotiating table.”

Here Long refers to the pioneering theory of child psychoanalyst Melanie Klein’s, of the “good and bad breast” and the infant’s response to it.

“The breast upon which the infant is so utterly dependent must be destroyed because of that dependence,” notes Long.

Viewed from this perspective, “the relevance of Kleinian theory for a psychological analysis of fallism becomes obvious upon recognising the equivalence of elite institutions with the nourishing breast”.

The University of Cape Town, he writes, “dispenses precious knowledge, financial support, networking opportunities and — above all — the promise of a life of dignity”.

Long notes that often poor and working- class families believed that education was “everything” and “the only thing no one can take away from you”. “But for fallists — some of whom come from impoverished backgrounds — the tragedy is that the internal logic of the institution is ‘white’. They feel themselves deprived of the fruits they imagined a university education would confer, triggering for many the familiar feeling of deprivation.”

Students felt persecuted by an institution “experienced as massively shaming”, and this shame turned into resentment, which, in turn, morphed into envy.

“In a literal display of anal sadism, they set about spoiling the university, unloading bins of human faeces into lecture halls. Haunted by a relentless sense of grievance, they set fire to life-affirming artworks and shut down life-giving classes of knowledge,” writes Long.

But the tragedy, of course, is “the more the fallists destroy the institution, the more impoverished the collective ego feels”.

“The feelings of helplessness triggered by entering a world not of one’s own making are overwhelming; the envy thus activated cries for everything to fall — not only the curriculum.”

The politics of decolonisation became the politics of displacement, notes Long.

“It does not stand on its own ground, being fundamentally a reaction against the Enlightenment tradition.”

With regard to attitudes to industrial-scale corruption, Long notes: “Just as activists acknowledge the relationship between inequality and violence without ever identifying the connecting tissues of shame, resentment and envy, mainstream analyses of corruption are similarly lacking in psychological understanding.”

Long approaches this through the psychodynamics of “lack and desire”.

“After all, there is something to be said about corruption — or unregulated consumption — in a social landscape scarred by centuries of deprivation.”

Greed was inevitable in this context and in fact was “the cousin of envy”.

“Both states suggest preoccupation with a prized commodity: the man of envy is powerless over its supply; the man of greed devours it as he wishes, when he wishes.”

It is a happy coincidence, therefore, that life in South Africa is shaped by the hopeful concept of ubuntu — an idea so widespread that it has virtually become a national export.

With regard to white South Africans in this matrix of shame, envy and impasse, Long suggests that being forced to live in a world that can no longer be taken for granted is a destabilising experience.

“The dice was loaded in their favour for hundreds of years and they have only now had their stride broken.

“Some attempt a kind of rapprochement by admitting a sense of ‘guilt’ about their arbitrary ‘white privilege’. Yet this does not achieve purchase with black people for whom such confessions read like another attempt by whites to recentre themselves in the national conversation — this time through their own victim-like pathos.”

Black people no longer submitted to the fantasies of white people, who were “exiting the dialectic en masse, leaving the madam and master without a raison d’être”.

So what to do?

“The shameful person cannot tolerate — let alone inspect — their own wound, so they inflict wounds on others.

“The envious person cannot accept their dependency, so they destroy the only source of goodness in their life.

“And the person who finds themself at an impasse is incapable of authentic human relating unless the relationship in question is defined by a degrading form of power.”

These, said Long, “are the dominant emotional tones of life in South Africa”.

In classical psychoanalytic theory, hope was conceptualised as residing in the individual, but the author regards it “as something that can also be held between people”.

“It is a happy coincidence, therefore, that life in South Africa is shaped by the hopeful concept of ubuntu — an idea so widespread that it has virtually become a national export.”

But the idea that individuals were “free to be whomever they want to be is ideological in the extreme, since it suggests that our social contexts — however dire — can be overcome through the simple ruse of exercising ‘mind over matter’”.

It is certain, however, that “the juggernaut that is life in South Africa has violence oozing from its every pore”.

To heal, we need to begin to understand “the manifold connections between the political and psychological domains” and psychology can “assist us in recalibrating our distorted relationships” in accordance with the Golden Rule, which is possibly the only universal moral principle that, as a species, we have ever known.

The situation, although critical, is not beyond the realm of hope. And, as one Chinese aphorism goes: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.”

Yet “this wound we call ‘apartheid’ will continue to be picked at compulsively. In both mind and practice, empathy has its limits; the relational pathologies of shame, envy and impasse are here to stay,” reckons Long.

And he adds that, “no matter the reparative attempts: there is a brokenness at the heart of our nation that cannot be wished away”. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Good scholary article. Long is on the right track to make psychology relevant. Some misconceptions need reworking, eg. ubuntu being an export concept (it is long dead) and the notion that everything must be destroyed if one cannot adapt. The reasons for corruption also deserves much more research.

A crucial reflection and analysis of the psyche of many South Africans, with some insights that may explain aspects of Judith February’s reflections on the rebuilding of libraries !

A great article but I believe it is looking for reasons to explain a situation that is a breakdown of society. To indicate that is is due to certain western ideas is erroneous as we again face the dilemma of “root cause”. Maybe it is time to use African psychology like the Philippines. Stop the GIGO

My take on this is anthropological and the power of story. South Africa is a society of clans. The story of the clan is that my clan defeated your clan and took your cattle. Ubuntu refers to members of the clan, not society in general.