CHICAGO BLUES

Biltong, beskuit & a braai in not-so-sunny Chicago

So what if there’s a tagine that tastes like a bredie or a bratwurst that tastes like boerewors? Who decides what’s authentically ethnic food and what isn’t? Certainly not the snobs in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The author supports Isabelo, chef Margot Janse’s charity which feeds school children every day. Please support them here.

As I’m writing this, winter is finally receding. I’m talking about Chicago winter, not that imposter they call winter down south. A few days ago I went outside for the first time in months without having to spend 10 minutes struggling into my snow boots and cold weather gear.

It’s hard to explain to people not used to this kind of weather what a schlep even a short drive to the supermarket can be. Any kind of mishap, like a flat tyre for instance, can turn life threatening in minutes. Unless you’re all togged out in a parka, hat, mittens, insulated boots, etc, you are definitely a candidate for hypothermia or frostbite. And then, when you get home, everything has to come off again. A tedious little ritual that repeats itself every time you leave the house. Needless to say, after the first few weeks our front room is covered in discarded winter gear for the duration. Just imagine trying to get kids ready for school every day. And don’t even think of driving anywhere without a snow shovel in the boot, in case you get stuck.

So inevitably my thoughts begin to drift south. I’m not yet desperate enough to start reading Afrikaans poetry but I’m getting close. And to make things worse I have to look at friends posting stuff on Facebook about going for strolls on the sunny slopes of Table Mountain, or along Sea Point at sunset. Or frolicking around sunny little Karoo towns in shorts and sandals, gobbling biltong. South Africans should be ashamed of themselves. Anyway, this is also the time of year that I develop serious cravings for biltong, rusks and boerewors. In that order.

There are quite a few online shops here in the States selling South African groceries like All Gold jam, Bisto, Robertsons spices, Cerebos salt and Ouma rusks. I can understand people ordering rusks. I have been ordering rusks for many years because they don’t exist here. And there is no equivalent. But All Gold jam or Cerebos salt?

I can live with Ouma rusks. As a matter of fact, on my last trip to South Africa people kept recommending Woolies rusks. I tried them and found them way too crumbly. They disintegrated the moment you dunked them in your coffee. So I just ignored all the raised eyebrows and stuck with Ouma’s. I could see people thinking that I’ve finally become unhinged after all these years in America.

Oh and biltong. These places all sell vacuum-packed biltong, or what passes for biltong. The biltong available here is another matter. If you want to pay R600 for half a kilogram of something that tastes like over-spiced tree bark, be my guest.

Chicago in midwinter, 2021. (Photo: Chris Pretorius)

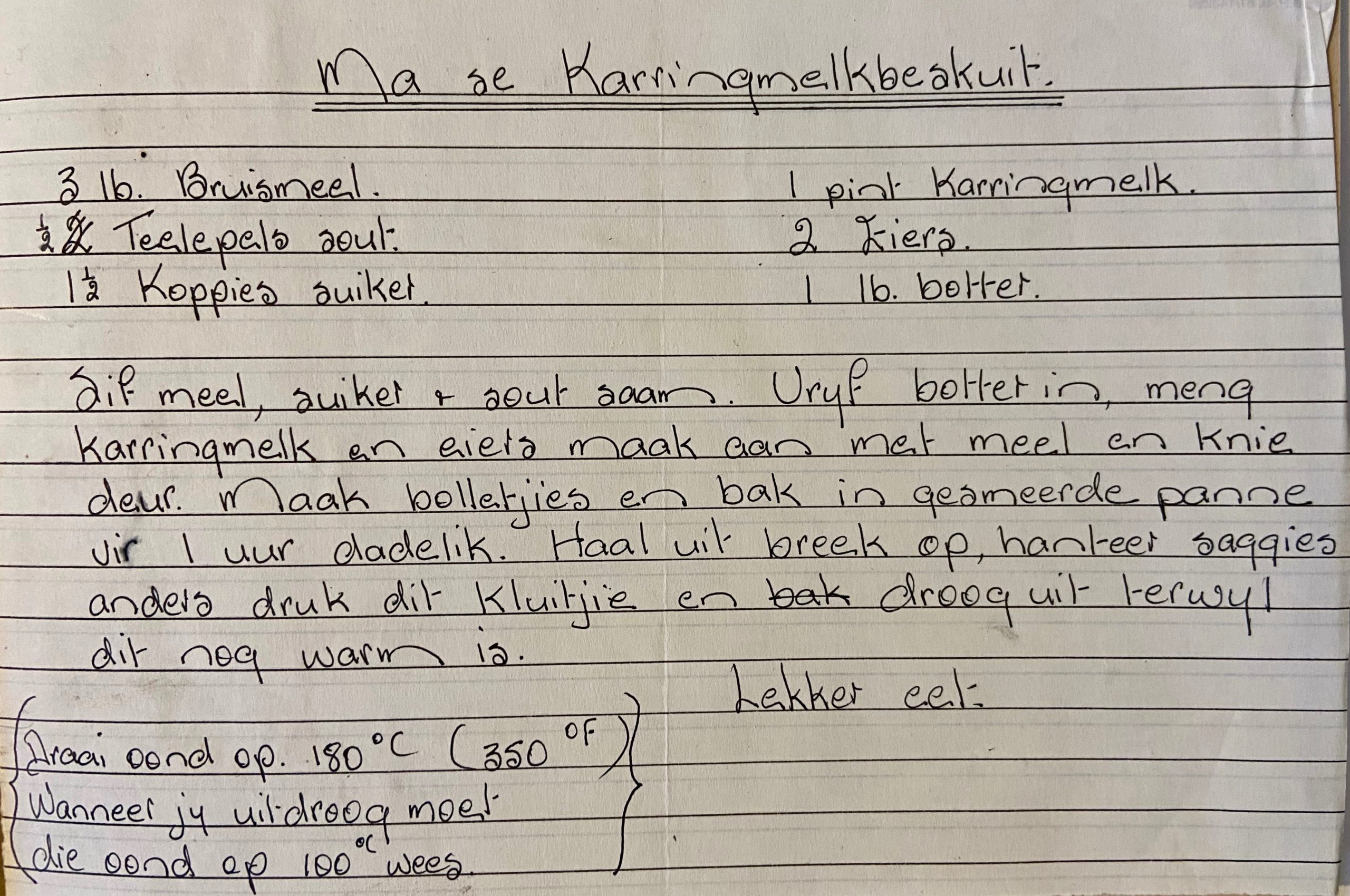

Chicago winters can and do strange things to you. And add the Covid-19 lockdown to the winter mix and things seriously start to suck. And when things start to suck people do all kinds of stupid stuff. For instance, this person decided to make rusks and yes, biltong. I came across a buttermilk rusk recipe my mom wrote down for me more than 30 years ago, just in case I developed an urge to make her rusks in faraway Chicago. Well, I did develop the urge. And I can tell you, it was worth it. There is nothing like a homemade buttermilk rusk to bring back memories of lazy mornings on a sunny continent far, far away. I’m not quite sure why I imagine all my mornings were lazy or sunny back then but it’s a nice comforting morning thought.

Buttermilk rusk recipe my mom wrote down for me in 1990. (Photo: Chris Pretorius)

I was a little more hesitant about taking on biltong making but after months of nagging by my son, Willem, I finally gave in. Willem got totally hooked on biltong during our last few trips to South Africa. So we made a contraption out of a plastic bin and two USB fans, strung up strips of beef with paper clips and, voila, to my utter surprise, we had perfect biltong within days. I’m still flabbergasted at how easy it is. I had done a lot of online biltong research and ended up being totally confused. People saying you had to do this or you had to add that, on and on. I even came across someone sprinkling Aromat on sliced biltong and sticking it in the microwave! Absolute sacrilege to a person like me living in a place with a severe biltong deficit.

My son Willem loading the biltong machine. (Photo: Chris Pretorius)

Anyway, I decided to ignore all the noise and keep it simple. I soaked the strips of beef in malt vinegar for a few hours, then dunked them in coarse salt, pepper and toasted coriander seeds, strung them up and hoped for the best. I didn’t even pat them dry. Absolutely no fuss. Biltong experts will probably laugh at this. Maybe it’s beginners luck but all I can say is that it tasted as good as anything I’ve had in SA.

To me, nothing is more authentically South African than biltong and beskuit. And maybe bobotie. Actually, on second thoughts, I would elevate bobotie to the “authentic” category. Then of course there are mopane worms, waterblommetjies and rooibos tea.

Buttermilk rusks and biltong Chicago style! (Photo: Chris Pretorius)

The Dutch and Germans make very similar tarts to melktert and I even found a German bratwurst that tasted exactly like boerewors. In Morocco I tasted tagines that were remarkably similar to bredies, for instance a lamb and green bean tagine flavoured with a dash of coriander and ginger or a lamb, tomato and potato tagine with a touch of herbs and cinnamon.

I know all of Europe has some form of double baked bread and seafarers introduced the idea to the Cape but there really is something unique about South African rusks. I spent a lot of time browsing rusk recipes and finally decided to use my mom’s because it was basically identical to the most basic or “authentic” buttermilk rusk recipes I found. And, well, it’s my mom’s. Also, my mom was not exactly an enthusiastic cook and this was the only recipe I inherited from her.

Speaking of moms, all this thinking about biltong and rusks and “authenticity” reminds me of my mother-in-law. She lives in San Francisco, the world capital of food snobbery. If you thought Capetonians were bad, you haven’t met any San Franciscans yet. The moment you move into the San Fransisco zip code area, you automatically become a pretentious, arrogant, culinary know-it-all. No matter if you can’t boil an egg or can’t tell the difference between cilantro and fresh coriander (It’s the same thing; this is a dig at the TGIFood Ed – TGIFood Ed). Minor details because hey, you live in the San Fransisco Bay area. Or just “The Bay Area”, as those in the know refer to it. And if you happen to snag a table at Alice Waters’ restaurant, Chez Panisse, you are definitely travelling in exalted food snob circles. Needless to say, definitely not the ideal kind of person to have as a dinner guest in a roughneck Midwestern city like Chicago.

So during her first visit, many years ago, she kept hovering around the kitchen, watching me at the stove, a sceptical eyebrow raised. I could see what she was thinking. Not only is this guy not from the Bay Area, he’s not even from Chicago. He’s from Africa! What the hell could be bubbling away in those pots?

“So what is this …. uhm … dish you’re … uhm … making …er … called?” she asked. “Don’t know,” I replied. “Just throwing some stuff together and see what happens kind of thing.” Regte boerseun answer, that. Not good. So the next time she popped the question I was ready. “It’s West African,” I answered. Bingo! Her eyes lit up, my cooking suddenly legitimised. “It smells delicious!” It’s authentic something or other, but at least it’s authentic. As luck would have it, not only does Africa have a West coast, it also boasts an East coast! Problem solved. We could happily dine up and down the African coastline for years to come. Americans are aware of Middle Eastern and North African food but venture a little south and you’re entering the mysterious realm of Food from the Dark Continent.

But what makes food authentic? I remember going to a Chinese restaurant in the Bay Area that everybody said was the most authentic Chinese restaurant in the city. It was a real hole in the wall place with formica tables and crowds waiting outside to be abused by the proprietor. He had this whole schtick of yelling at customers at the top of his voice to hurry up and finish eating and telling people what they should order and just being utterly unpleasant. Everybody was thrilled. Wow, this is so authentic! It’s real! To me it felt like I was part of some Disney re-enactment. And the food was just okay. But who cares about the food when the whole experience is so “authentic”.

It dawned on me that if the poor proprietor tried to put tablecloths on the tables and stopped the screaming act, he would lose his clientele quicker than you could say chop suey. He was acting out a Western fantasy of an authentic Chinese dining experience. Authenticity actually means ethnic. And he was trapped in his little act. This doesn’t only apply to Chinese food. American diners tend to rate the “authenticity” of any ethnic food from outside the borders of the US and Europe. You never find people rating the authenticity of, say, their French dining experience. Recently an Indian restaurant had to close down in New York despite great reviews because they tried to take a more innovative approach to Indian cooking and break away from the same old traditional stuff. But New York diners were having none of it and stayed away. I’m talking pre-lockdown here.

A few years ago a young Mexican-American chef, Diana Davila, opened a little restaurant, Mi Tocaya Antojeria, right across the street from me, to great acclaim. She has since won a number of national awards and was named one of the young American chefs to watch. But I recently saw an interview with her complaining of all the Facebook and Twitter attacks against her every time she dares to stray from “authentic” Mexican food to do something more innovative. It was sad because she seemed really disillusioned and disheartened. Now that you will never find happening to young white American chefs or European chefs. Mind you, I’ll exclude Italy from that but they only have themselves to blame. Italy is an interesting case. In the last few decades there’s been an explosion of culinary innovation in Europe, for instance. Starting in Catalonia, Spain, then Scandinavia (chefs going out and foraging for food), it spread across Europe. But not in Italy.

Italy was totally obsessed with the authentically traditional and innovation wasn’t tolerated. There are even organisations, some government-sponsored, guarding Italian culinary traditions. Needless to say these organisations were mostly run by middle-aged men. As a matter of fact, there’s such an organisation right here in the States passing judgement on Italian restaurants. Who needs that? Least of all young chefs trying to do something new. In the last few years there has in fact been the stirring of rebellion among young Italian chefs and their battle cry is, “Kick Nonna out of the kitchen”. About time. I never had a Nonna in the kitchen in the first place so I never had that particular problem.

So who decides what’s authentically ethnic and what isn’t? Somewhere along the line somebody must have chosen certain recipes and declared them “authentic”. I think it has a lot to do with the emergence of printed recipe books. As far as Mexican food is concerned, the “authentication” moment happened in 1972 when an English author, Diane Kennedy, published The Cuisines of Mexico. I have a copy and the recipes are perfectly fine, but almost instantaneously it became hugely influential inside and outside Mexico. She started the idea that any Mexican food north of the border wasn’t authentic Mexican food, never mind that most of Texas and the Southwestern United States was part of Mexico until just over a hundred years ago. Kennedy wasn’t solely responsible for the idea of a very static notion of authentic Mexican cuisine but she certainly contributed. She is now nearly 100 years old, lives in Mexico City, and still calls the shots on what’s authentic and what’s not, although younger chefs are starting to reject her opinions. It’s hard enough to get taken seriously in the US; who needs an old English biddy nipping at your heels back in Mexico City.

It is really quite common to find cookbooks impeding the creative development of certain cuisines. For instance in the 1930s Nikolaos Tselementes published the first comprehensive Greek cookbook in Greece and it became the bible of authentic Greek cooking for generations of housewives. Problem is, his training was based on French cuisine and is now acknowledged to have been a complete bastardisation of traditional Greek cooking. But it reigned for nearly a century. He actually invented “traditional” Greek dishes like moussaka and pastitsio. And speaking of recent inventions, the baguette, synonymous with Parisian cuisine, was only invented in the 19th century. And think of pizza. By the time pizza became popular in Italy, large numbers of Neapolitans had already emigrated to New York and were making New York style pizza. So which is the more authentic? It can be argued that there was a kind of parallel development between Italian and New York pizza. Speaking of recent developments in Italian cuisine, what would Italian cooking be without those little fruits native to the Americas, aka tomatoes? Or Chinese cuisine without chilli peppers, also native to the Americas?

So what is authentic cooking? And is it even important? Do I really care that there is a tagine out there that tastes exactly like a bredie? Or a bratwurst that tastes like boerewors? While researching biltong and rusks I realised that it wasn’t authenticity I was looking for. It was a taste memory. That first awareness of the taste of biltong is forever lodged in my brain. And it’s personal. Everybody probably has a different biltong taste memory. I have a taste memory of my aunt’s roast chicken from more than 50 years ago and I’ve tried to recreate that taste for decades and failed. She hardly ever used spices so her method was really simple, but try as I may, I just can’t get it right. I also have taste memories of her over-sugared mashed pumpkin and overcooked mashed green beans.

I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with people wanting authentic food. Of course cuisines reflect cultures and traditions but those cuisines were always innovative and people based their cooking on what was available at the moment. Or affordable. Through the centuries cooking practices were never static but always dynamic and rooted in reality. Centuries ago you wouldn’t have had some dude abusing the hospitality of a bunch of Berbers in the Moroccan desert by announcing that the food they’d just prepared for him didn’t meet his requirements of authenticity. The point is that the food was prepared with love and care. Authenticity is beside the point, reality is what is on the plate in front of you. So shut up and eat already.

In the meantime, I’ve set my sights on making “authentic” Chicago boerewors. I will keep you posted. DM/TGIFood

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.