OP-ED

The location of social housing in Cape Town: Separating fact from fiction

The clash over what constitutes the ‘inner-city’ of Cape Town exemplifies a crucial fact about social housing: It is all about location. Social rented accommodation in the right place is truly transformative. It facilitates the upward mobility of working-class black families by enabling access to economic opportunities, decent schools, healthcare, parks and public safety.

Arguments about location are centre stage in the heated debates over social housing in Cape Town. The City’s Mayoral Committee Member for Human Settlements, Malusi Booi, claims that social housing has been built in the inner city since 1994. This contradicts the argument underpinning Ndifuna Ukwazi and Reclaim the City’s Western Cape High Court victory over the sale of the Tafelberg site in 2020.

In their leave to appeal, the City of Cape Town and the Western Cape government question the focus on the CBD and argue that projects further afield are equally well located. According to Booi: “Cape Town also has many CBDs and urban centres requiring well-located housing, and it is not appropriate for a court to arbitrarily determine which type of housing should be built where” (Daily Maverick, 8 April 2021).

The clash over what constitutes the “inner-city” exemplifies a crucial fact about social housing: it is all about location. Social rented accommodation in the right place is truly transformative. It facilitates the upward mobility of working-class black families by enabling access to economic opportunities, decent schools, healthcare, parks and public safety. Living closer to work reduces commuting time and cost, which releases time and resources for domestic responsibilities and family life.

Today’s investments in social housing will impact on generations to come by giving children better access to quality education, a secure home environment and social and professional networking opportunities.

Social housing is also a powerful tool to integrate different communities and promote urban restructuring. Indeed, it is the only housing policy instrument with an emphasis on location and an explicit mandate to tackle the apartheid spatial form. This is done through partnerships involving social housing institutions, beneficiaries and the private sector. It is also best achieved through an integrated, area-based approach, rather than piecemeal projects. The benefits of mixed neighbourhoods and more inclusive cities are well understood internationally.

Given the importance of location to social housing, where are Cape Town’s projects located within the metro? We draw on a new study to answer this question. Compared to other metros in SA, Cape Town has surprisingly few social housing projects. While Cape Town makes up almost 20% of the total metro population in South Africa, it has roughly 10% of the national social housing stock. None of it has been built in the CBD since 1994. This remains a major shortcoming, given the economic and social significance of the central city, and the need for redress and transformation. Instead, there has been a “spatial drift” of isolated projects towards the outer city over the past decade, with some signs of positive change that require stronger support.

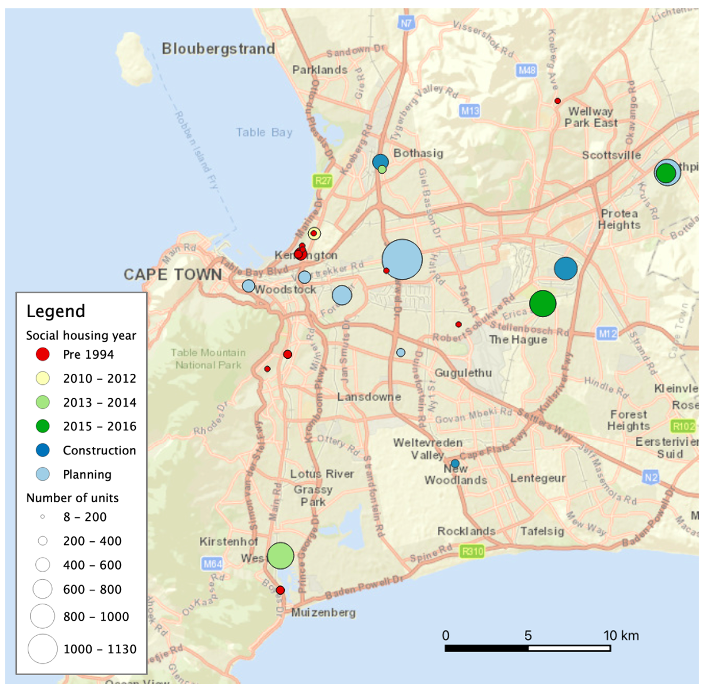

Social housing projects in Cape Town

Source: Authors based on projects registered with Social Housing Regulatory Authority.

Past and present projects: Spatial drift

The map shows social housing projects built before 1994 (red circles) and after 1994 (yellow and green circles). The size of the circle reflects the number of units built. All the pre-1994 projects were developed by Communicare, and mostly in the 1990s. They are relatively close to the city centre, with a cluster in Brooklyn near Paarden Eiland. Two others are in the desirable Rondebosch and Newlands areas.

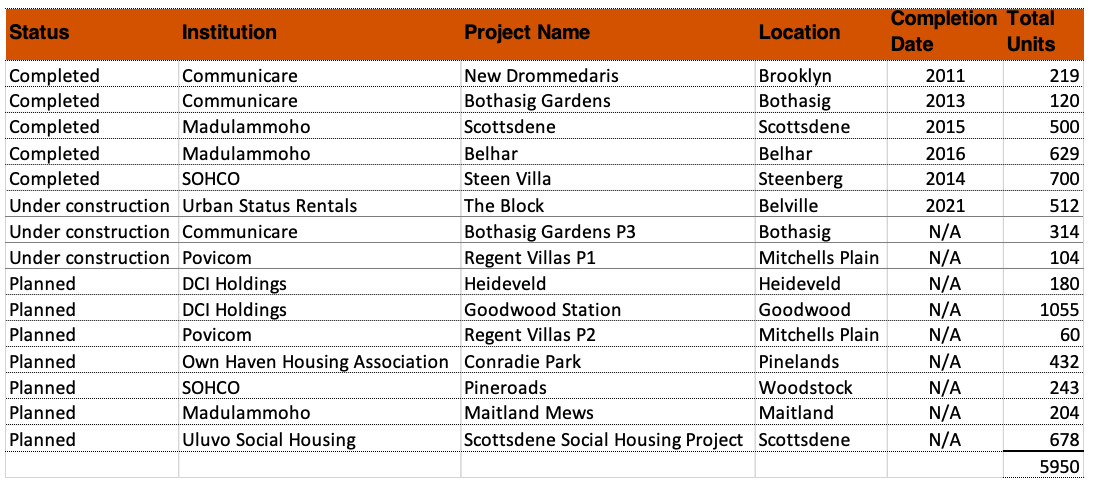

Since 1994, Communicare, Madulammoho and SOHCO have developed and managed only five new projects. Communicare built two small projects in 2011 and 2013, creating 219 rental units in Rugby (Brooklyn) and 120 units in Bothasig. The third phase of Bothasig Gardens is under construction and expected to yield 314 units once completed. These projects are located in the “inner suburbs”, which are close to major transport routes (N7 and N1) and the secondary economic node of Century City. The number of rental units is small compared to the three projects developed by Madulammoho and SOHCO (see three large green circles in the map).

Madulammoho’s Scottsdene (500 units) and Belhar (629 units), and SOHCO’s Steenvilla (700 units), are the biggest and most significant social housing projects in the city so far. They are all in the “outer suburbs”, far from the jobs and amenities of the central city. The trend for social housing to be located in outlying areas is exacerbated by two projects that are currently under construction. Urban Status Rentals is developing 512 units in Bellville, which is nearing completion and occupation. Povicom (a private-sector company) is building Regent Villas. It will yield 104 units in Weltevreden Valley, Mitchell’s Plain.

Social housing’s spatial drift into outer suburbs and townships is common across the metros, as discussed in our report. The pressure to accelerate delivery, the costs of well-located private land, and the limited release of public land have contributed to the rise of peripheral greenfield projects.

While these may still be well-managed and close to public transport and secondary business hubs, they do little to bring about spatial restructuring and social integration. The racial and social characteristics of tenants usually replicate those of the surrounding community, which means that little mixing takes place. In fact, many of the tenants move from the immediate neighbourhood into social housing, which limits its transformative impact on households, neighbourhoods and the city (see our report on social housing and upward mobility).

Future projects: Signs of improvement?

There are some signs of improvement when future projects are considered. Some planned schemes are located closer to the inner city, including projects with many units (light blue circles). Three planned projects are located in suburbs along the Voortrekker Road Corridor: Woodstock, Maitland and Goodwood station. Goodwood alone is expected to yield 1,055 units. The fourth is part of Conradie Park in Pinelands, which should generate 432 social rental units within a larger mixed-income project. Locating these schemes close to the Voortrekker Road Corridor makes sense because it has been earmarked for major public infrastructure investments. Social housing can make a positive contribution to regenerating this extended precinct and ensuring that affordable rental accommodation is available.

Social housing projects in Cape Town (since 1994)

Source: Social Housing Regulatory Authority.

Cape Town’s social housing pipeline leaves a gaping hole in and around the core city, including Sea Point and the Atlantic Seaboard. There are no plans for even a single project here. Yet the financial feasibility of social housing as part of mixed-income developments was proven in the Tafelberg case. Other parcels of public land that could be released for social housing have also been identified. Given the moral and policy obligation to promote spatial transformation, and the tragic history and exclusive character of the central city, it should not be devoid of social housing investments.

Even if larger projects can be built elsewhere in the city, schemes in the CBD would perform a unique symbolic function. Social housing in the central city would demonstrate an unprecedented commitment to transformation, inclusivity and diversity. Tafelberg could be the first step in this direction. DM

Dr Andreas Scheba and Dr Justin Visagie are senior researchers in the Inclusive Economic Development Programme of the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) and senior researchers/lecturers at the University of the Free State (UFS). Professor Ivan Turok is Distinguished Research Fellow at the HSRC and holds the SARCHI Chair in City-Region Economies at UFS. The research was funded by the EU Commission’s research facility on inequalities.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.