MATTERS OF OBSESSION

Brian Eno’s ambient music for times of thinking and healing

From the early 1950s, rock music became the soundtrack for city life, the thrashing snare drums and jangling of electric guitars reflecting and colouring the soundscapes of a cacophonous industrial civilisation. By the mid-1970s the guitar was being replaced by the synthesiser and the timbre of popular music began to change into varieties of other textures. Harassed urbanites needed respite from the sounds of traffic, blaring radios, humming fridges, televisions – and fuzzed-up guitars. There was a need for calm and silence, for the emptiness that allows for reflection and meditation. Enter Brian Eno.

There has always been music that soothed rather than stirred the soul, that acted as a balm instead of a stimulant. But ambient music has many roots: John Cage’s 4’ 33”, first “performed” in 1952, forced “listeners” to focus on four minutes and 33 seconds of silence, drawing attention to the sound of everyday life. In the even earlier “furniture music” of Erik Satie a piano plays simple but beautiful melodies organised around moments of silence. Satie intended his music to “mingle with the sound of the knives and forks at dinner”. In the minimalism of Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Philip Glass, figures repeat themselves unendingly, with minute changes introduced at imperceptible intervals.

Brian Eno ‘invents’ ambient music

In 1978, Brian Eno released Ambient Music 1: Music for Airports, the first in his series of four albums titled Ambient Music. Eno had already achieved stature as a musician (Roxy Music), producer (of U2, Talking Heads) and theorist of music. And he had made a startlingly innovative album, No Pussyfooting, with guitarist Robert Fripp of King Crimson, as well as Discreet Music, both of which can be seen as instances of ambient music before the genre received its name.

Eno was much influenced by the minimalists, but also by the non-art experiments of the Dadaists and various avant-garde artists. More immediate predecessors included the “cosmic” music of German electronica band Tangerine Dream, formed in 1967, whose album Phaedra (1973) presented haunting melodies whispered by synthesisers.

Eno’s methods of music-making drew on chance and randomness, cut-up and techniques transplanted from other disciplines, often going in the direction of a mistake instead of editing it out. Discreet Music was a result of his fascination with tape recorders, which allow for long segments to be repeated and overlaid by other segments.

He has never been a master of any particular instrument, instead dabbling with many in search of the strange and different. He famously used the recording studio itself as an instrument and often described himself as a non-musician. He also produced artistic works in other fields, especially in the visual arts.

Music to think with

With the Ambient series, Eno wanted to produce music that would allow the listener to be immersed in some activity without the music intruding into the consciousness those activities needed – writing, thinking, making, and even relaxing. Yet he wanted the music to have presence, to seep into what was happening, and able to be listened to as a work, interesting in itself, worthy of attention. He defined ambient music in contrast to muzak, that species of sound played through speakers in lifts, hotel lobbies and wherever real music was too real to be tolerated. Anaesthetised muzak was designed to improve productivity on the conveyor belts of factory production.

Instead, Eno wanted music that had “atmosphere, or a surrounding influence: a tint”. The music should “accommodate many levels of attention without enforcing one in particular”.

The result was Ambient 1: Music for Airports, the first of a series of four albums. A set of four beautiful pieces, the album does everything Eno wanted it to do: it is contemplative, relaxing, ignorable and yet worthy of repeated listening. The pieces are slow, repetitive and meditative, with small changes that are barely noticeable, staying in mind long after the music has stopped.

“We like to watch ourselves think and feel. We like to be presented with new things to have feelings about. We like to be surprised at our own feelings,” Eno explained.

The beauties of Harold Budd

He worked with Harold Budd, a composer who had given up on music before being saved from obscurity by Eno, who produced The Pavilion of Dreams in 1978. It is a haunting album, four pieces for voices, piano, celeste, glockenspiel, vibraphone, marimba and percussion. Budd regarded it as “the birth of myself as a serious artist”.

Juno, the last track on the album, is astonishingly beautiful, full of ravishing chords quietly rippling on the piano, voices accompanying with long, sombre single notes. Drenched in melancholy, the piece nevertheless evokes tiny bright lights with its percussive attacks: on vibes, marimba and glockenspiel. Full of silences and decaying notes, I found the piece suddenly playing in my head years after I had last listened to it.

The second album in the Ambient series, Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror, was a collaboration between Eno and Budd. Released in January 1980, it reeks of the type of beauty found on The Pavilion of Dreams. Simple yet exquisite melodies are played on the piano with the lightest of touches, the notes reverberating long after they have been struck.

Interestingly, Budd quietly repudiated the notion that all his work could be categorised as ambient music, and he took pains to distance himself from the minimalism he dabbled in before working with Eno.

Many have mentioned Satie in connection with Budd, and the association is justified: Satie too mastered a kind of simplicity that was alluring and yet full of complexity, minimalist long before the emergence of the compositional movement.

Budd’s music is not so much a statement in support of peace, gentleness and thoughtfulness as a performance of these eternal verities. Listeners can’t but yield to the pacific soundscapes he paints with his musical brush. His music expresses a philosophy at odds with the speed and havoc of modern and postmodern industrial life. His is not a music of cities but of the glade, of late-afternoon sunlight and nightly moonbeams, moments that inspire reflection and equanimity.

And it is pretty, something Budd himself was not afraid to proclaim.

Laraaji and Eno

The third album in the Ambient series was Ambient 3: Day of Radiance, in which Eno presents the music of Laraaji. Eno “discovered” the multi-instrumentalist busking in Washington Square Park, where he would improvise for long periods on his electronically modified zither. A student of Eastern mysticism, Laraaji had studied composition, violin, piano and trombone at Howard University before taking to the streets to offer his music to passers-by.

The final album in the series is by Eno himself, titled Ambient 4: On Land. It is a startling addition to the other three, consisting of music organised around the sounds of sticks, stones, nature and animals, sometimes slowed down to primeval effect. This is ambient music turned sombre, its dark tones perhaps hinting at apocalypse.

Other musicians were also producing similarly thought-inducing works around this time. The works of Midori Takada, a Japanese composer and percussionist who studied African percussion and Indonesian gamelan, match the work of Eno. Her first solo album, Through the Looking Glass has been hailed as an “ambient minimalist masterpiece”.

A proliferation of sub-genres

In the late 1980s ambient music was taken up by younger musicians such as The Orb, who removed the percussion from their acid house creations to produce “chillout” music, the band members doubling as “ambient DJs”. Their debut, The Orb’s Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld, was hailed by critics as a groundbreaking album, frequently included in Best Album lists of the period. It changed the ambient scene, taking the genre into the nightclub, giving birth to a sub-genre, “ambient house”.

Aphex Twin produced many ambient works. Beginning as a DJ in the 1980s, Richard David James, who is Aphex Twin, released Selected Ambient Works 85-92 in 1992. James has achieved stature as a composer, his works – which have been described as a sub-genre, intelligent dance music (IDM), a categorisation he has rejected – performed by the London Sinfonietta and Alarm will Sound.

Sub-genres have rapidly evolved, reflecting the dissemination and popularisation of the original concept, and we now have “illbient”, IDM, ambient dub, ambient house, ambient techno, ambient industrial, and even ambient pop.

But there have been less interesting offshoots as well, such as the vapid New Age music that has saturated the music scene. The sense of what ambient music is, its nature and its function, has changed since its emergence, and after Eno produced an album titled Music For Films, we now have music to sleep by, to eat by, and to relax with, among many others.

And one group, The Black Dog, produced Music for Real Airports as a spoof of Eno’s album, with pieces that reflect that “airports tend to reduce us to worthless pink blobs of flesh”.

By the time of the Ambient@40 International Conference held in February 2018 at the University of Huddersfield, the concept of ambience had been applied to a range of extramusical activities. There are now phenomena such as ambient marketing, ambient media, ambient intelligence and ambient poetics, as well as considerations on the subject in philosophy.

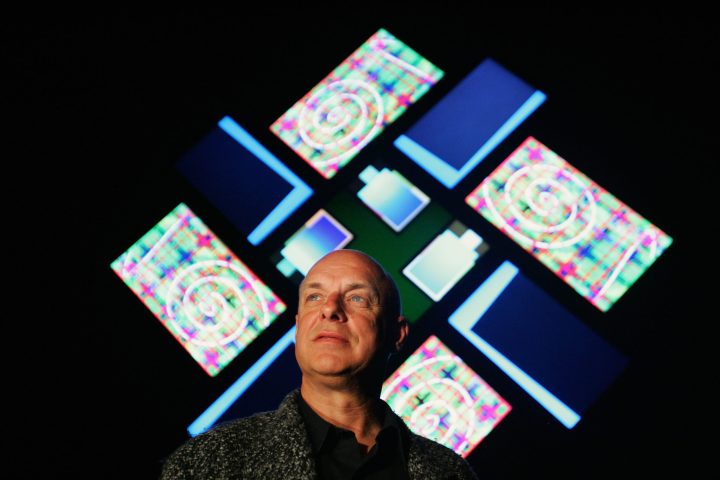

Artist and music producer Brian Eno speaks during a photo call for ‘Luminous’, a program of musical events being hosted by the Sydney Opera House as part of Vivid Sydney on May 26, 2009 in Sydney, Australia. (Photo by Sergio Dionisio/Getty Images)

The healing power of music

More recently ambient music has attracted listeners yearning to soothe their troubled states of mind arising from the horrors of the Covid-19 pandemic. The death of Harold Budd in December 2020 saw many checking his music out and getting hooked on its beauty.

A recent article in The Guardian noted that there has been a slew of ambient releases in 2020, and goes on to speculate about how the music is a cure for “the claustrophobia and drift of isolation”. DJ and producer Richard Norris has launched a Music For Healing series, while Julianna Barwick has released an album titled Healing Is a Miracle.

In their introduction to the book Music Beyond Airports: Appraising Ambient Music, Monty Adkins and Simon Cummings write: “Anecdotal references to ambient decreasing anxiety or aiding study is borne out by academic research that demonstrates the effect this music can have. Of one study examining ambient music and wellbeing, Michaela Slinger writes that: ‘A study at Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge determined that ambient music therapy had a positive effect on postoperative patients’ recovery by improving pain management and decreasing the negative effects of environmental noise.’”

Appraisals of ambient music

Some have been critical of the moods ambient music evokes, accusing the genre of being apolitical. In Against Ambience Seth Kim-Cohen says: “Ambience is an artistic mode of passivity. Its politics, that is, the kind of relation it fosters with the world in which it exists, is content to let other events and entities wash over it, unperturbed. Ambience offers no resistance.”

Eno’s notion of “doubt and uncertainty” is part of his aesthetic stance, far from passive orientation to the world. And Eno is far from apolitical: he is a left-inclined activist who has voiced support for the Palestinian cause, for Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn – who was seen by many as too far left – and is horrified by Donald Trump and the nationalisms he has unleashed. “We’ve been in decline for about 40 years since Thatcher and Reagan,” he said in a 2017 interview.

According to Adkins and Cummings: “Lawrence English in his 12 notes towards a future ambient writes that ‘ambient is never only music for escapism. It is a zone for participation in a pursuit of musical listenership that acknowledges sound’s potential values in broader spheres (the social, political, cultural, etc). It is a freeing up, an opening out and a deepening, simultaneously.’ For English, ‘ambient is never only music. It is a confluence of sound, situation and listenership; moreover, it’s an unspoken contract between the creator, listener and place, seeking to achieve a specific type of musical experience.’ In its ‘tinting’ of the environment ambient engenders an individuated listening experience on each hearing.” DM/ML

Other significant ambient/electronica works:

Phaedra (1974) by Tangerine Dream

Through The Looking Glass (1983) by Midori Takada

Monoliths & Dimensions (2008) by Sunn O)))

Illusion of Time by Daniel Avery & Alessandro Cortini

Watermusic II by William Basinski

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Fantastic! Thankyou I could get addicted to this😊

A timeous review. I also recommend another Eno collaborator, Jon Hassel – trumpeter extraordinaire.