COPYRIGHT ACT

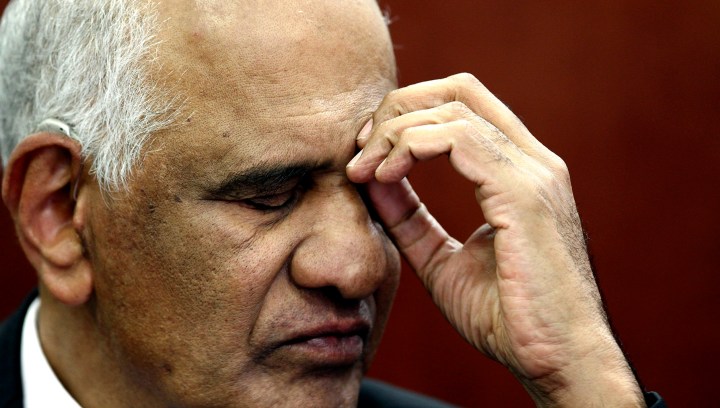

Growing up blind: Retired Judge Zak Yacoob helps challenge an archaic law

Retired Constitutional Court Judge Zak Yacoob, who has been blind since he was 16 months old, has submitted an affidavit in support of Blind SA’s application to the high court to ensure blind and visually impaired people have access to materials in their preferred format.

Blind SA, represented by the public interest organisation SECTION27, has launched a case in the Gauteng High Court against what it believes is the state’s failure to legislatively redress the outdated Copyright Act of 1978. The law makes no provision for people with disabilities and their need to access works in accessible formats such as braille.

Read: Challenge to the constitutionality of ‘outdated’ Copyright Act heads to court

We publish Yacoob’s affidavit in full:

I am a retired judge of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, and have been blind since the time I was 16 months old, consequent upon meningitis. All the facts in this affidavit are within my knowledge.

I have been asked to make this affidavit in support of an application aimed at ensuring that blind and visually impaired people have access to materials in their preferred format available to them without hindrance and delay. All I will do is give my own experience of being blind without access to reading material.

I went to a school for the blind in 1956, at a time when braille material was hardly available in this country. In the first few years at school, we had three types of reading materials available to us, courtesy of England and the United States of America.

The first were prescribed school books for reading, printed by the Royal National Institute for the Blind in London. These books were meant for that particular market. This often meant that we had to read about concepts and ideas that were alien to us, which we struggled to grasp and understand, such as “white Christmas”, and old terminology that was very strange to us.

The next type of reading material we had available to us was religious literature. A religious organisation in the United States sent a large number of copies of the Old Testament and the New Testament of the Bible to the school. The rarity of reading material at the school meant that I read both the Old and New Testaments certainly more than twice.

The third and final type of literature available to us at the time were copies of Reader’s Digest from the American Printing House for the Blind.

As we grew older, things got a little better because the South African Library for the Blind made a limited number of books available to the school, but these were not prescribed works in terms of our curriculum. In fact, we had limited to no access to our prescribed works in accessible formats. This meant that the prescribed works had to be read to us by the teacher, or by some other person.

When we got to high school (the present “Grade 9” which we used to call “Standard 7”), some of the prescribed books were available to us, but we had only one copy for the whole class, and there were generally between six and eight students per class.

Things were not much better at university because prescribed books and any other literature were hardly ever available on tape or in braille. If I had not had someone to read to me, I would never have gotten by.

I started to practice as an advocate in 1973, and of course, legal textbooks and the law reports were not available at all in accessible formats for persons who were blind, but more importantly, leisure-reading books were also not available. Tape Aids for the Blind had a limited number of books available, and so did the South African Library for the Blind. But this limited number of books certainly did not fulfil my need to read.

When I became a more successful advocate, I used to buy my own books in ink print, and then I would arrange for them to be put into braille, which I and other people who were blind would use. I am still not sure whether that was proper legal conduct on my part, since I may have contravened the Copyright Act 98 of 1978 (“the Copyright Act”).

Of course, as time went on, more and more books became available, but they were far from what we — blind and visually impaired persons — required. The position at the moment is that if you can afford it, you could quite easily buy your own books and get them printed in braille for your own use. Of course, distribution of those braille books would in fact be an offence ultimately.

Those with a disability, and who are poor (and most of us are very poor) suffer the most because they cannot afford to buy books. They are dependent on the Library for the Blind or Tape Aids for the Blind. These institutions are dependent on copyright exemptions, which, absent exemption in the Copyright Act, require the consent of the publisher in order to make accessible formatted reading materials available. Therefore, a blind person’s ability to read is considerably hampered.

Even though I am an empowered blind person, the reading deficit was so big when I was a child that even today, my children have read more books than I have. I therefore believe that it is extremely urgent for books to be made available for blind and visually impaired people, in formats that they prefer (electronic, tape recorded, or braille), so that they can advance themselves.

My own experience tells me that it is impossible to express in words how urgent this is. The best I can do is say that every day that the present Copyright Act prevails in the form in which it is, literally thousands of blind and visually impaired people are deprived of reading material, and the prejudice to them is in fact irreparable, incalculable, and very difficult to put into words. I would suggest that even without it being put into words, the prejudice is obvious.

I would therefore support the idea that it is extremely urgent to ensure that reading material is available in formats in which blind and visually impaired people read them, and that the Copyright Act needs to be amended very, very urgently. I cannot overemphasise the fact that even one day’s delay, in my view, is too much. DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.