ANCIENT JOURNEYS

Wealth of wanderlust: The disastrous expeditions of Alexine Tinné

This is a cautionary tale about the assumption that, on any journey, money can buy you out of trouble. Alexine Tinné was a young, pretty, adventurous and enormously wealthy Dutch aristocrat.

She was widely travelled, headstrong, the only child of her father’s second marriage, adored and indulged by her parents. When she was 10 her father died and, on turning 21, her inheritance made her one of the richest heiresses in Europe. When her mother died she inherited even more. Money was almost limitless.

Life in The Hague entertained her but, eventually, bored her and she resolved to journey beyond the bounds considered reasonable for a young woman. Africa, in the mid-19th century, was just such a place.

***

Most Western travellers in 19th-century Africa had definite goals: the source of the Nile, the Mountains of the Moon or some legendary lake. Alexine explored for the sheer pleasure of travel. Being inquisitive, intelligent, young and rich was a distinct advantage. Travelling in the haute bourgeois style that extreme wealth afforded, however, was to be her undoing.

When she was 19 she embarked on a tour of Egypt, was entranced and set about learning to speak and write Arabic. A year later she convinced her mother Hendriette – a former lady-in-waiting to Dutch Queen Sophie von Württemberg – to accompany her on a camel trip to the Red Sea. Three years later, in 1857, she travelled up the Nile to Wadi Halfa before turning back.

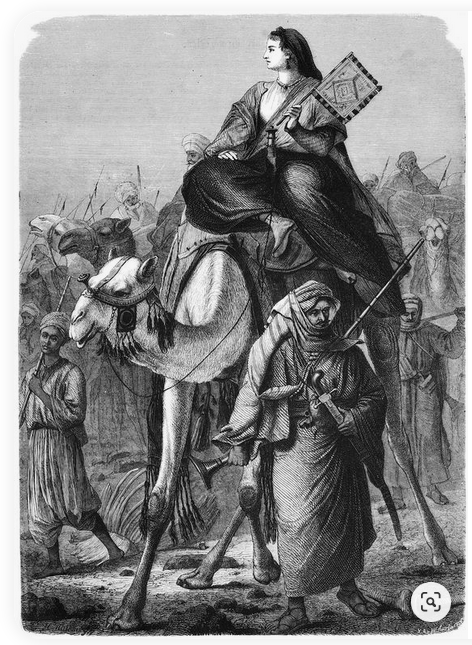

The voyage of Alexine Tinné (Image supplied)

The bug had bitten. Alexine asked her half-brother John to buy her a small steamer to be delivered to Cairo. Towing two boats with provisions, servants, hired soldiers, a horse, a donkey and five dogs, they got to Jebel Dinka south of Khartoum where supplies ran low and they were forced to return. No other European women had got so far up the Nile.

The explorer Samuel Baker, who was in the area, wrote that “there are two Dutch ladies travelling without any gentlemen. They must be demented. A young lady alone with the Dinka tribe… they really must be mad… ”

Alexine Tinné on a camel (Image supplied)

(Image supplied)

Alexine was undeterred and resolved to reach Bahr el-Ghazal (River of Gazelles) which she thought could be the source of the Nile. No expense would be spared. This expedition was massively equipped and cost around £10,000 and they added a “gentleman”, the geographer Theodor von Heuglin.

Apart from the steamer, there were two other boats with provisions, about 20 soldiers, four camels, 25 donkeys, a horse, five dogs, 65 soldiers, six private servants and “one female slave for the baking of bread”. Both Alexine and Henriette had at their disposal a Turkish officer with 10 infantrymen, an interpreter, two Dutch maids, Anna and Flore, plus some Arabian clerks and administrators.

Von Heuglin would later describe the expedition as “a huge, disorderly and rudderless machine”.

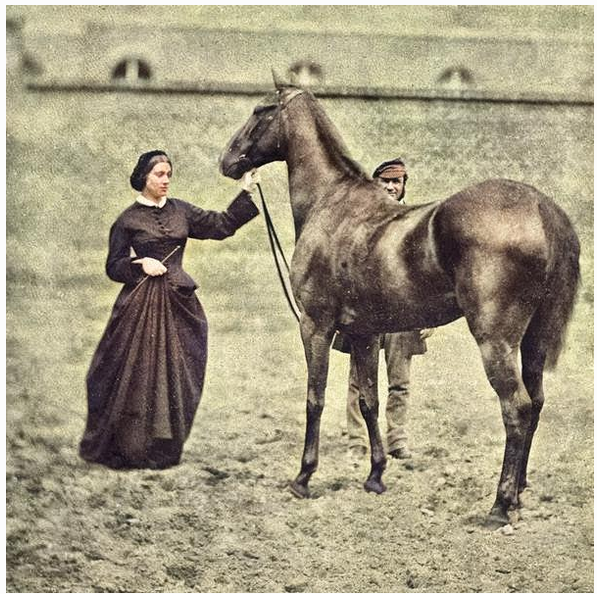

Alexine Tinné’s household staff in Algiers (Image WikiCommon)

To reach the River of Gazelles they had to steam 483km up the White Nile from Khartoum. When the water became too shallow for the boats, they set off overland toward the Jur River.

By then the rainy season had set in and soon they were in trouble. Storms lashed them with hail and lightning, their tents collapsed, they were constantly cold and wet. Worse, the soldiers hired to protect the party mutinied over rations. They were forced to depend on a slave trader who demanded ever-higher prices for food.

Alexine became seriously ill and no sooner had she rallied than her mother, her favourite maid Flora, and one of the servants came down with malaria and died.

The expedition eventually limped back to Khartoum, carrying the bodies of the dead. Alexine was devastated, depressed and unwilling to return to Holland to face criticism of her much-publicised failure. She bought a house in Cairo, then moved to Algiers where she acquired a large house with a “reduced” retinue of 15 servants to ponder her next move.

It would be, she decided, to cross the Sahara to Lake Chad and meet Touaregs along the way. Preparations began: an ice machine and two large iron tanks for water were a must, plus 70 camels and 50 people. Heading south in 1869, Alexine developed appendicitis and holed up in the oasis of Murzuq until she recovered. Then the caravan set off for Ghat.

At Wadi Berdjong a dispute broke out. It was thought by visiting Touaregs that she carried gold in the water tanks. Alexine emerged from her tent to try to quell it and a Touareg sliced off her hand with a sword then struck her again across her neck. According to an eyewitness she died of loss of blood. Her body was never found. She was just 33.

Portraits of Alexine Tinné (Images supplied)

A letter to her half-brother John shortly before the trip seemed to anticipate what was to come:

“If anything were to happen to me, during my travels, if I would be killed, which is a reasonable possibility, people might say, “she deserved it, that’s what happens with all that travelling, poor Alexine, what a way to die, etc.

“But you will not do that and you will not lament me. I have never understood the happiness of growing old. I always found something sad in it – even under the happiest circumstances – and I don’t find the thought of dying happily and courageously by a knife wound or a gunshot frightful instead of dragging through a boring life, as I have seen many.

“Maybe it is shocking to think this way. If you hear today or tomorrow that I have been sent to the other world, then don’t think my last moments were lived in bitterness. Overall I have been content about my life – I have lived well. I have had fun. I am in no hurry to die – but if it happens, fine – a short life, but a happy one!”

Poster for the Tinné exhibition The Hague (Image supplied)

Most of Alexine’s collection of photographs (she taught herself photography) and ethnic artifacts were housed by John in the Liverpool Museum. On May 3 1941, during World War 2, a bomb landed on the building, destroying most of the collection. Those artefacts stored in Holland were rediscovered and exhibited in 2013. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.