MAVERICK MAPPER

Road tripping and Karoo dreaming

Nearly half of South Africa consists of flat semi-desert which can be both terrifying and alluring. Don Pinnock went exploring the heart of the Nuweveldberg Plateau in search of hazy memories and a sandwich.

Long before dawn I would be coaxed out of bed and shepherded into the back seat of the car, still clutching my pillow. There I’d fall asleep again, with the tassels of the travelling blanket tickling my cheeks.

Hours later I would wake to the hum of the engine and the smell of egg-and-mayonnaise sandwiches. Up ahead the road would stretch out endlessly, while the side-windows offered a featureless blur of brown veld and distant, flat-topped hills. We’d be going somewhere strange and exciting: Cradock, maybe, Graaff-Reinet, Molteno or some farm lost in the vastness of it all. But to get there time seemed to stretch like the rubber band trapping the grease-proof paper round my sandwich. I’d stare out the window at the cloud towers and vast blue sky, unsure whether I was awake or dreaming

Photo by Don Pinnock

Photo by Don Pinnock

I once asked – I must have been about six – why the road went on for so long. I still remember my mother’s reply: “It’s the Karoo, dear.”

As far back as I can remember, the Karoo, that vast, flat tableland which comprises much of South Africa’s interior, has reminded me of huge distances, slow-moving time and egg-and-mayonnaise sandwiches.

The sandwiches were absent, but all the other ingredients were in place as my son and I turned off the N1 at Matjiesfontein and headed for the distant Komsberge and the village of Sutherland. The road sped beneath our vehicle, but long before it reached the horizon all movement seemed to slow to zero. The speedometer told me we were moving, but we didn’t seem to be going anywhere.

It was an illusion, of course, because the village of Sutherland eventually hove into view. A couple of kilometres before reaching it I turned off onto a secondary road and bumped along to Skurweberg Guest Farm.

“Hi, I’m Witjan,” said its owner, emerging from a shed wiping his hands on a cloth. “Let me show you the place.”

The Southern African Large Telescope on July 07, 2018 in Sutherland, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images / Sunday Times / Esa Alexander)

Photo by Don Pinnock

Photo by Don Pinnock

Photo by Don Pinnock

The guesthouse was a neat building fronted by a thick lawn looking incredibly green for the semi-desert surrounds. Witjan and Elsa van der Merwe whipped up beer and a braai. As bats hawked moths in the veranda light we talked about seeds, horse traps, Land Rovers and the size of the Karoo. That night we tucked up to the sound of large, ripe peaches plopping onto the lawn outside the window.

Before dawn the next morning we were trussed up in Witjan’s open Landy and heading for the Roggeveld Escarpment. One can coo over 4x4s, polish them, use them as status symbols or keep them in a garage until the family holiday. But there’s nothing to beat hacking your way up a mountain in a tough workhorse you don’t mind bashing. I can’t imagine how we got there, but Witjan suddenly skidded to a halt a mere metre from the escarpment edge. The view was head spinning.

To the south, at least 100km away, was the Witteberg range, the southernmost rim of the Karoo plateau. To the west – with the Teapot clearly visible – was the Cederberg and east, perhaps 200km distant, was the Swartberge. Far below the valleys were still swathed in dawn shadow. Wisps of mist were beginning to rise from the stream beds. Somewhere, somehow, I’d seen this before. But the memory wouldn’t surface.

Photo by Don Pinnock

Photo by Don Pinnock

Photo by Don Pinnock

That afternoon, with the silence of Skurweberg still ringing in my ears, we drove into Sutherland and found the silence unbroken. The place reminded me of a shootout scene from a John Wayne movie: two cowboys walking slowly towards each other, hands poised above their guns, as the rest of the townsfolk step behind walls and doorways, interested but silent. But in Sutherland the gunmen were absent.

We checked into The Cottage run by Rudi Blom, who nudged my memory about the sort of guys I used to hang out with in the 60s. He showed me an Alfa Romeo he’d restored and a motorbike on which he’d done every conversion imaginable. I guess, in the Karoo, you need to be able to eat up kilometres.

He runs a fine little guesthouse in a laidback way. If you get him in the right mood he’ll tell you the sort of filigree stories only a small town can generate.

Enquiring about places of interest round the village, we were directed – via the dominee who had the key – to the Van Wyk Louw Museum. This brilliant Afrikaans poet began life in Sutherland and his works now share the museum with the rather frugal pickings of former cabinet minister Adriaan Vlok and the more prolific paraphernalia of dam builder Sir Hendrik Olivier. But if you need something with more depth of field, Rudi can arrange a visit to the huge telescopes of the nearby astronomical observatory.

The heat was starting to climb as we rolled out of town on the R356 and by 10am the horizon was jiggering with mirages.

“Would you like me to drive?’ my son enquired.

“No, it’s okay. I like driving these long stretches,” I countered.

“Well, would you mind if I slept in the back seat?”

The Ou Pastorie Museum in Fraserburg. (Photo by Gallo Images / GO! / Jac Kritzinger)

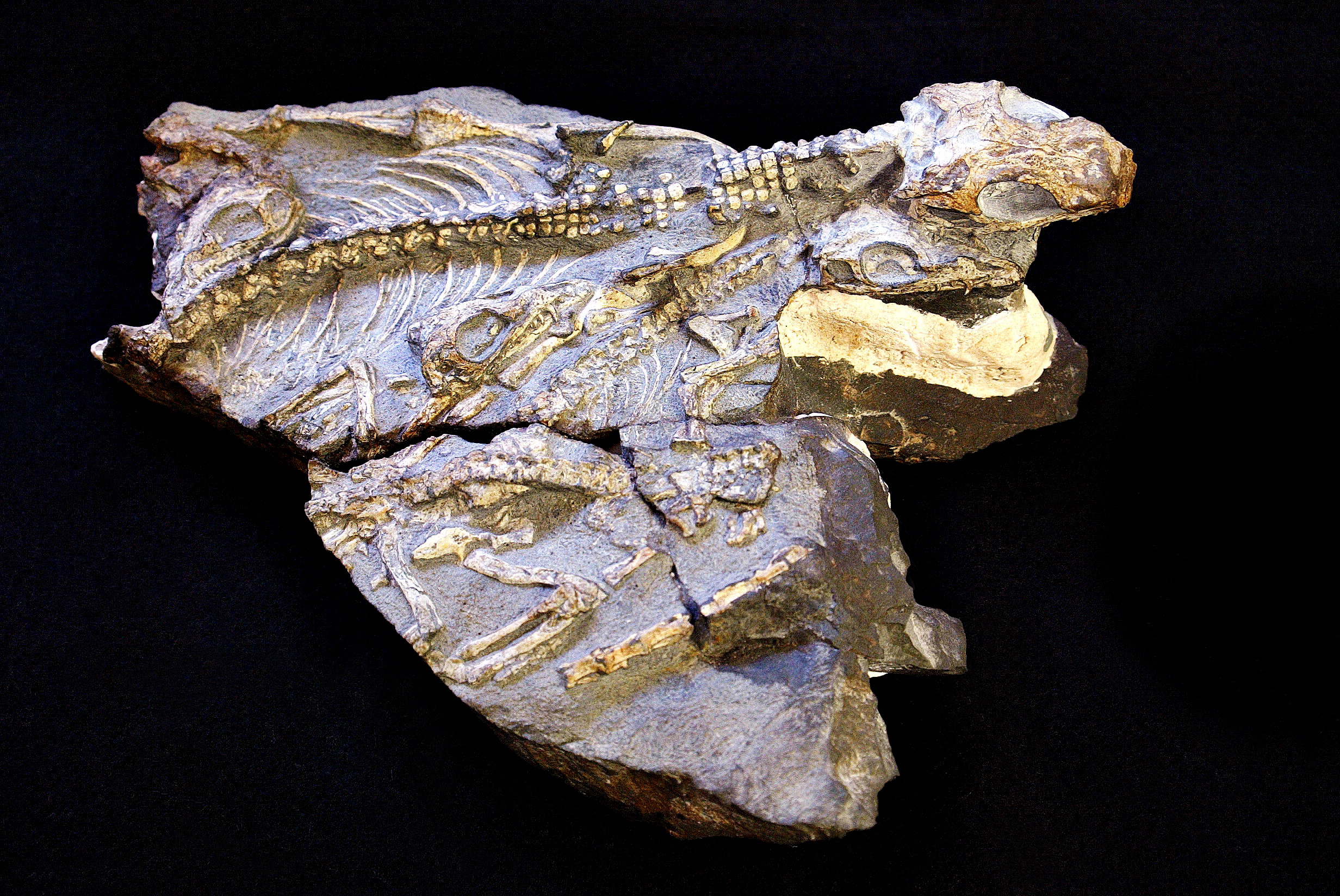

17 September 2007. This fossil which was discovered 12 years ago in Fraserburg has been identified as a 260 million-year-old Pelycosaurus, which is believed to be the earliest evidence of parental behaviour in animals. Photo Gallo Images/ MEDIA 24 PTY LTD (NEWSPAPERS)

Fraserburg, when it finally appeared, turned out to be famous for its monsters. The story goes like this: about 250 million years ago, in the late Permian age, a huge river (which no longer exists) burst its banks and spilled muddy water onto a floodplain. When the water subsided large pools remained. Worms popped up, leaving squiggles in the sand, an aquatic arthropod wandered along, some fish left tail marks in the mud, then a few dinocephalians came stomping up to investigate. These duck-billed reptiles – up to 3m long – lumbered over the mud, followed by a heavily armoured bradysaurus.

The mud dried and the tracks would have eventually blown away. But a week or so later the river flooded again, covering them with a thin layer of what would later harden into sandstone.

The trackway was eventually buried under maybe a few thousand metres of sediment, then millions of years later it was exposed again along the spillway of a farmer’s dam.

Today the Gansfontein Paleosurface is the village of Fraserburg’s pride and joy, and in the village museum dinocephalians, diictodons and other creatures share space with, among other things, boere kitchenware, old village photographs and a Victorian pram.

Just outside is a curious old clock tower known as the Peperbus and a neat corbelled hut made entirely of stone. Some of these extraordinary round huts are national monuments, built by early settlers in the absence of wood. Why gravity doesn’t claim their rock-lapped roofs is remarkable.

Later we dropped in to the local café for something to drink and a sandwich, but they didn’t make sandwiches. When I asked the man at the till how things were these days, he said 90% of the people in the village were over 70 and there were only three white kids in high school.

We saw many happy schoolchildren and a good few adults under 70, but I guess when you’re just passing through a village you can’t expect a precise census. Fraserburg is the quintessential Karoo dorpie and we’d have liked to stay longer, but time and the road drew us onwards.

Beyond the town my son switched on the radio and the tuner began to track for stations, the dial spinning uselessly through the FM bands. He had to switch it off to put it out of its hissing misery.

A young man rides along the R381 between Loxton and Beaufort West, followed by his dog. (Photo by Gallo Images / GO! / Jac Kritzinger)

***

The Karoo system covers about three-quarters of South Africa and its early formation (the Dwyka Series) took shape as the silty bed of a huge inland lake. A glacial period lowered the basin floor out of sheer weight, but when the ice melted huge sand and mud masses filled the plains again, forming the coal-rich Ecca Series.

This was followed by a period of steady rain and a boom in animal and plant life. This period, captured in sedimentary rocks known as the Beaufort Series, has yielded the greatest number of fossils known to science.

The present cycle is dry – the Karoo receives less than 250mm of rain a year. Its name is derived from the San word Kurú which implies dry and harsh. In 1812, the German explorer Martin Lichtenstein (who later founded the Berlin Zoo) described its form rather well: “There are large spaces which are perfect plains, but these are intermixed with eminences.”

Some fine eminences made their appearance along the R356 to Loxton. I stepped out of the car into the heat to photograph them and discovered the roof of the vehicle had been hiding the main performance: clouds. The flatter the land, of course, the bigger the sky. But blinding-white cumulonimbus towers in the Karoo-blue heavens suggested a canvas with its frame off somewhere in infinity.

Just when I had the feeling my real-life painting had no edge, the road took a sharp right turn and there was Loxton. If ever there’s a village in South Africa which gives you the sense of being an oasis, this is it. Only the red-brick church spire peeps above the trees which clothe the place in a virtual woodland.

A view of the main road in the rural town of Loxton. (Photo by Gallo Images / GO! / Jac Kritzinger)

After the vast, dry plains, Loxton’s lawns seem shockingly green. Leiwater flows along deep gutters beside the streets, to be sluiced into gardens according to a weekly roster.

It would take no more than 10 minutes to walk clear across the village. The houses are mainly old, well tended and unselfconsciously picturesque, the police station has no razor wire and the library is full of books. The only sound mid-morning was the chatter of fat sparrows.

Without romanticising the place, it is one of the most laidback, pretty and desirable villages around in which to send down your rural roots. We paused to drink in the shade along a leafy street and a silver Rolls-Royce slid out of a garage down the road – someone off to fetch the morning paper. I suspect there’s a lot more to Loxton than meets the eye.

We didn’t overnight in the village but at Jakhalsdans, a 20,000-hectare farm and wildlife reserve nearby. It simply confirmed the unusualness of the area. Four generations of Van der Westhuizens have grown up there and each must have added something beautiful. Its gardens are park-like, the buildings would, I’m sure, have featured in Country Life and the extensive guesthouse is packed with the sort of antiques it takes generations to acquire. Cala of the fourth generation was there to greet us.

Among his many stories over a fine evening meal was one about Danie van Graan of Loxton who, in 1975, saw what he thought to be a caravan landing in his sheep camp. As he approached three beings with high foreheads regarded him from the windows. Suddenly a beam hit him and his nose began to bleed so he backed off. Danie watched for a while, then his “caravan” lifted off and disappeared in seconds.

As dawn touched the high pines we staggered away from a large farm breakfast and headed down the R381 towards Beaufort West. It’s a beautiful road – or was I just relieved to see the endless plains broken by two mountain passes? The Molteno and Rosesberg passes ease you down from the Nuweveldberg Plateau through the Karoo National Park and into Beaufort West, which seemed large after Loxton.

***

It’s an attractive little town with one abiding disadvantage – the main street is also the N1 highway between Cape Town and Johannesburg. This means that every day about 1,500 articulated trucks and countless cars roar through.

We overnighted in Clyde House which, sadly, closed down shortly afterwards, and next morning peeped into a museum full of heart surgeon Chris Barnard’s awards and trinkets and explored the impressive Dutch Reformed Church. The heat was melting the tar outside.

In Beaufort West we finally found some egg-and-mayonnaise sandwiches, then set off down the long road to Cape Town. The smell of the sandwiches permeated the vehicle and we were unable to resist for long. We pulled over and scoffed the lot.

“Can I drive?” enquired my son as we prepared to hit the road again.

“Sure. Do you mind if I curl up in the back seat?”

“No problem.” DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Having just returned from a similar trip (Barkly East, Craddock, Somerset East and the spectacular Baviaanskloof Wilderness) I realized that South African’s have an amazing country to explore – our own. One good thing to come out of this Covid period.

A masterful wordsmith with stunning accompanying pictures to embellish the artistry of a journey through time and place.

Kanu, Agree. I loved reading and being carried away with this beautifully descriptive writing. Thank you!

I agree. Beautifully written and I identify as I have a rural karoo getaway and a big delight is the four to five hour drive through the vast spaces held in the wide arms of the mountain ranges where one can stretch your eyes

I have just road-tripped in my mind. Thank you, Don. The main photo is magical. I would love to wake up to that, even a replica on my wall would do it. It was on my screen when my daughter saw it and remarked on it, mentioning the indefinable spirituality bound up in the vastness of the Karoo, where one’s “real-life painting has no edge”.