MATTERS OF OBSESSION

Simphiwe Ndzube’s magical, borderless world of celebration

Ndzube’s work is an alternative reality in which the boundaries between the possible and impossible, the visible and the invisible, and fact and fiction dissolve to reveal a transformative imaginary world.

“Any space where you are able to stop and recreate your own reality in whatever way is an act of resistance,” Simphiwe Ndzube told Lindsay Preston Zappas on the Carla project podcast.

A “born-free”, raised in post-apartheid South Africa, Ndzube’s reality is that of a South African immigrant and artist who has been living and creating in Los Angeles for several years. The art he makes is a reimagining of epic proportions; Ndzube begets an entire world that he is “constantly in the process of expanding and creating as a way to allow imagination and opportunities to come to life”.

Based in a fictional landscape named Mine Moon, Ndzube’s world takes its name from “the space that has characterised the apartheid geographical layout of South Africa”. It stems from the postcolonial reality of an exploited land and people, stripped of natural resources, devalued and shoved into tiny, limiting boxes so as to further the colonial mission.

The characters that populate Mine Moon are a reimagining of the bodies of colour that were so brutalised by the apartheid regime, limited in all aspects of their lives. These are the bodies that were told where they could go and where they couldn’t, where they must live and where they mustn’t, who they were allowed to love, what they were able to achieve and what they could believe in.

The Mine Moon that Ndzube cultivates, however, takes these oppressive boundaries and tramples them in its dynamism. It is an ever-morphing, fluid and limitless place. The characters who inhabit it are shifting, fantastic and complex – almost grotesque in their genderless ambiguity. Their forms, free from any restriction, exist half on the canvas and half off; they crawl or roll across the gallery floor and swing from ropes attached to the ceiling.

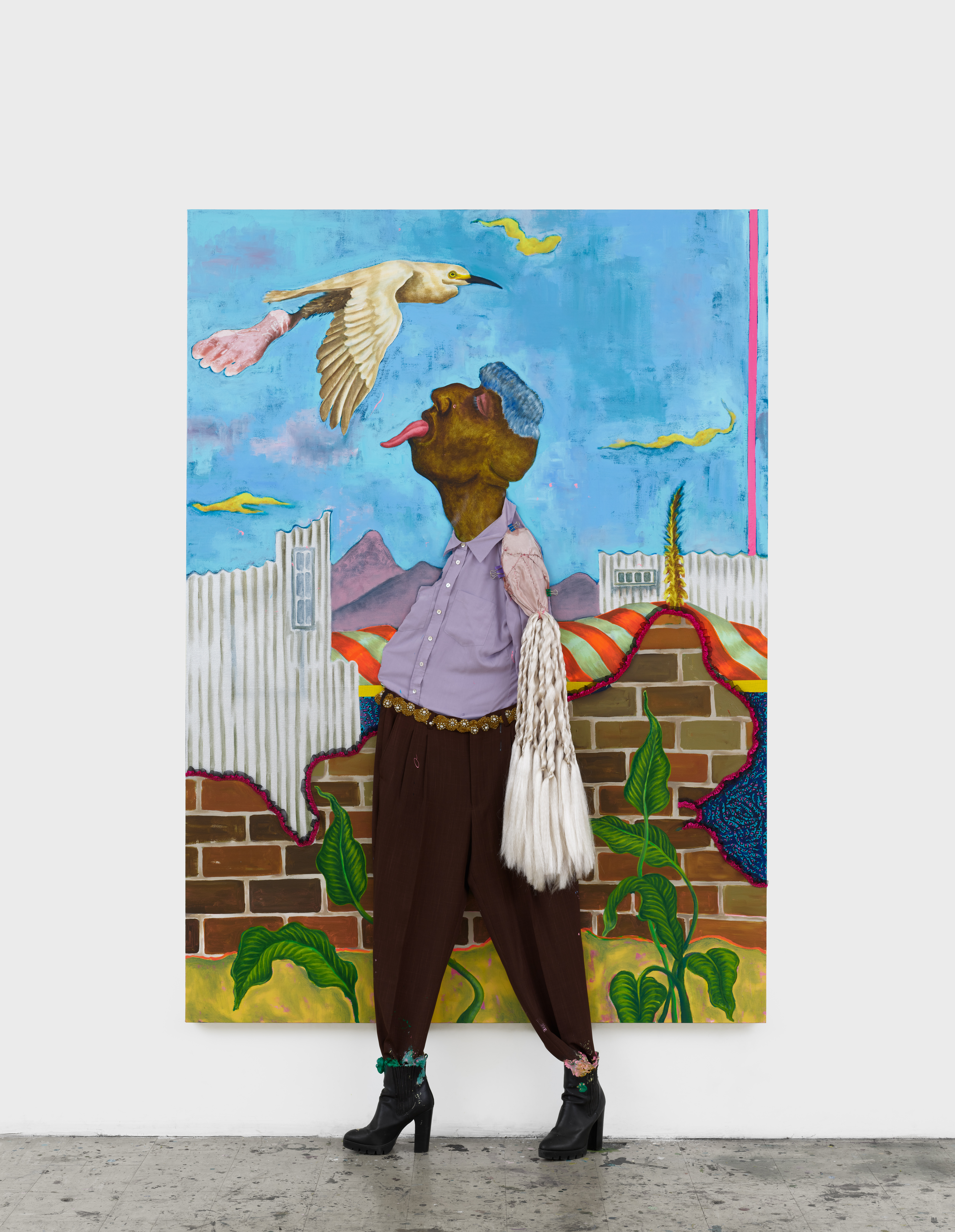

Tender Song of Melodies Set Free, 2020. The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana at Stevenson Gallery; Photograph Simphiwe Ndzube, courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Mine Moon “offers new possibilities of being and becoming for the shack dwellers of South Africa. It reimagines the borders created to limit movement and imagination,” Ndzube explains. The fantastical world acknowledges the “betrayal and broken promise” of a new and democratic South Africa that continues to plague South Africans of today in the form of blatant and racially divided inequality and poverty. But it also imagines an alternative reality, in which the lines between fiction and fact, the visible and the invisible, and the thinkable and unthinkable are continually traversed.

Ndzube takes significant inspiration from the literary genre of magical realism, naming Gabriel García Márquez, Zakes Mda, and David Lynch among the influential figures for his work. The genre, which incorporates fantastic or mythical elements into otherwise realistic fiction, blurs the already thin line between reported fact and the imagined.

As They Rode Along the Edge. The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana at Stevenson Gallery; Photograph Simphiwe Ndzube, courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam, Cape Town and Johannesburg

In an essay about Marquez, the British/Indian novelist Salman Rushdie wrote that magical realism is a “development of surrealism that expresses a genuinely ‘Third World’ consciousness”. The genre “deals with what Naipaul [the late Trinidad and Tobago-born British writer] has called ‘half-made’ societies, in which the impossibly old struggles against the appallingly new, in which public corruptions and private anguishes are more garish and extreme than they ever get in the so-called ‘North’, where centuries of wealth and power have formed thick layers over the surface of what’s really going on”.

Post-apartheid South Africa is a great example of Rushdie’s “Third World consciousness”. The ghosts of past traumas haunt and clash with the national myths surrounding our new democracy. How can we call independent South Africa a “rainbow nation” when so many of its towns are still shadowed by poorer twin townships whose populations overwhelmingly comprise people of colour? Or when most private schools have a student body that is disproportionately white? Wealth disparity is just one of the many aspects of contemporary South African life that continue to be clearly and heartbreakingly racialised.

Abagula Ngenqgondo Abayolwanga by Simphiwe Ndudze; Photograph Simphiwe Ndzube, courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam, Cape Town and Johannesburg

The break between what we are told to believe and what is true opens up an ambiguous space in which things that happen do not really make sense: the absurdity of some political truths, the unsolved mysteries/deaths/disappearances that occurred during apartheid, the nonsensical rules arbitrarily enforced by racist policing systems; all of these things leave us in a kind of twilight zone, in a “half-made” space where crazy events do happen.

Mine Moon lives in this crack between reality and fantasy, but instead of letting the nation’s slippery grasp on truth weigh him down, Ndzube takes matters into his own hands. His work imagines a different reality, a space of celebration rather than degradation, of inclusivity in its wildest form. It’s a space of fantastical protest, a space of play.

“My work is so much based on openness. I bring to it what happens naturally, and I allow it to be what it wants to be.” Expanding on the importance of play in his work, Ndzube states, “play is imperative to holding onto innocence and the hopeful perceptions that you have as a child. Play – not in its naivety, but its adult form – much like stand-up comedy, gives space to discuss with humour and compassion what is otherwise extremely difficult to talk about. After play, there is space for experimentation, trial, error and failure as important strategies for how we make sense of the world.”

The fluorescent landscapes and acrobatic movement of Ndzube’s exhibition at the Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg embody the type of boundary-pushing play he speaks of. Called The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana, this iteration of Mine Moon is loosely based on the real Gwadana, a region in the Eastern Cape known as a mecca for witchcraft.

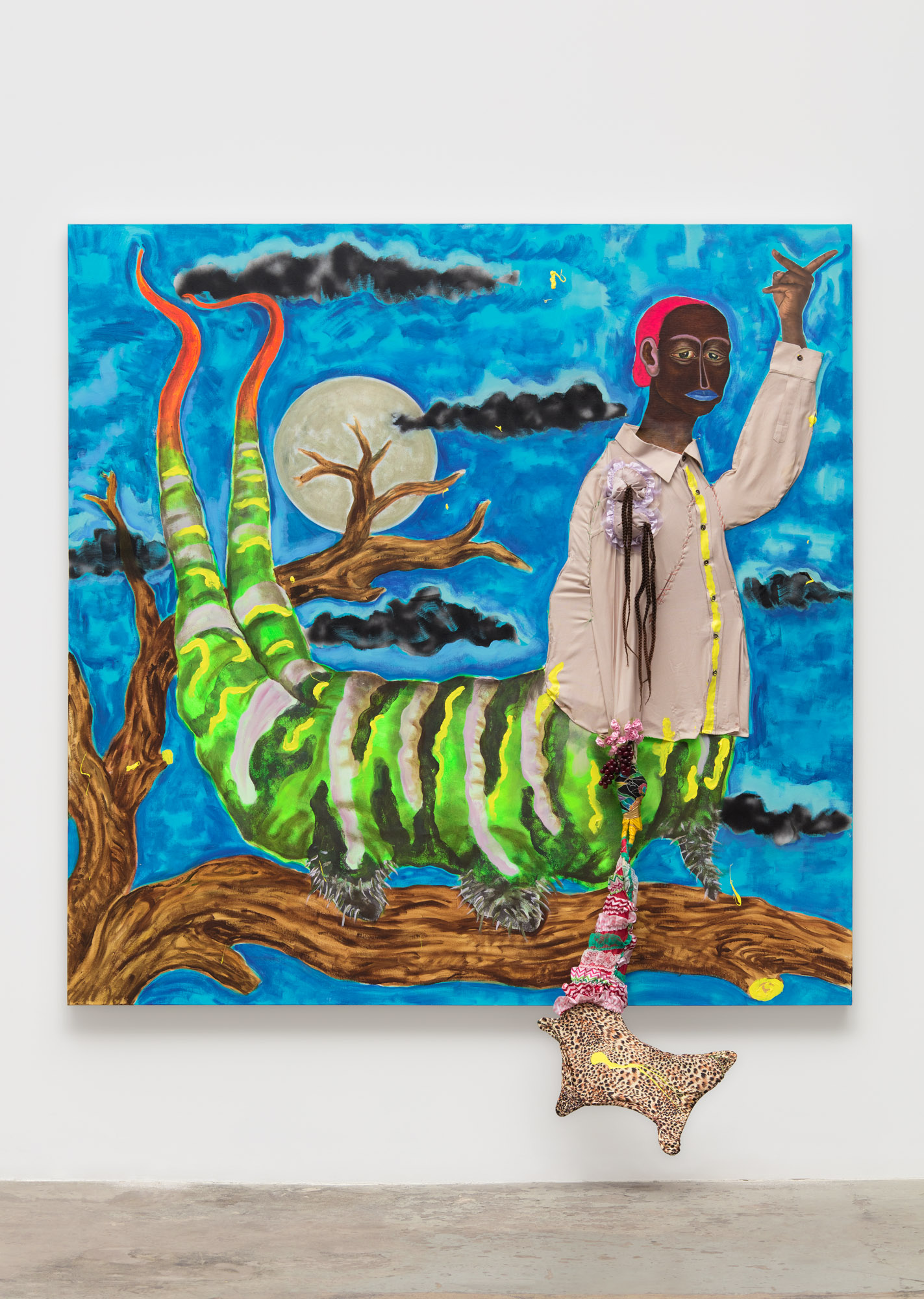

Once Upon a Time, Mine-Moon, 2020. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles; Photograph Lee Tyler Thompson, courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles and Bucharest.

“Legend has it that Gwadana is a place to be feared,” Ndzube explains. “It is a place that young Christians and priests speak about only when they are associating it with evil.”

Witch-hunting is an age-old and international phenomenon that often results in the harassment, persecution or execution of wrongfully accused community members, generally women. Ndzube’s playful rendition of Gwadana “sought to transcend the oppressive qualities within this legend and offer an alternative imagined scenario”.

The characters frolic among multicoloured plants and run-down but cheerful-looking buildings. In As They Rode Along the Edge a creature rides on the back of another creature which does a handstand on a wheel that rolls along an arcane crack. A Tender Song of Melodies Set Free depicts a human-like inhabitant of Mine Moon with an arm of rope that protrudes from the canvas looking like a feathered wing. It sticks its tongue into the sky, licking (or serenading?) a bird flying overhead that sports a human foot instead of claws.

“The Mine Moon characters in this exhibition celebrate their own oddities and vulnerabilities, depicting the fictionalised Gwadana as a type of utopia wherein the societally persecuted are finally celebrated as equals. These characters are beautiful outcasts exposing the irrationality within supposedly rational post-apartheid societal structures,” reads Ndzube’s description of the exhibition.

Ndzube takes a harmful myth and turns it on its head, celebrating otherness rather than shaming it. Importantly, The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana doesn’t shun the myth on which its inception is based (in the exhibition Gwadana it is still a mecca of witchcraft), it simply expands the myth to include a more positive and empathetic view of the outsider. The persecuted are “celebrated as equals”, not as better or worse than the persecutors.

I am a Bird Now, 2021. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

Secrets of the Fields, 2021. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

In a continuation of this inclusive celebration, Ndzube opened his most recent exhibition, Like the Snake That Fed the Chameleon, at Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles a few weeks ago. Taking its title from Solstice, an Audre Lorde poem about leaving the past behind and becoming a better version of herself, the exhibition makes use of strong symbols of transformation. The snake that sheds and the chameleon that changes colour are, like the characters of Mine Moon, perpetually changing/moving/morphing.

Rainbow Nation of God, Cities on the Sky. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

TaBhiza, The Flâneur, 2021. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

Individuation, Manifest, 2021. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

The Return from Heaven, 2021. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

The exhibition explores beauty in the erotic and the grotesque, “landscapes are transformed into sexual innuendos where water and blooming flowers suggest a season of spring and becoming”. This exhibition was Ndzube’s answer to the collective suffering and growth caused by the pandemic: “It is a declaration of a new season to come.”

But Ndzube also reminds us that time is cyclical, even in fantastical worlds. In thinking about the future, we must remember the past. The faces of the characters that now inhabit Mine Moon “are becoming the faces of the people that made up my adolescent world.”

Ndzube’s move to Los Angeles a few years ago “gave me a clean slate to reflect on what I thought home was. My reality of South Africa is based on my memory […] It’s like this play between how you remember and what you remember, and the more you remember it, the more real that story becomes.” Just like old myths, memories are malleable and fragile. They can be manipulated for the good or the bad. “In missing my African people, the tension between remembering and forgetting is being explored in the faces of these [characters.]” How we memorialise things, and how we cannot allow even our memories to become stagnant or oppressive, become central parts of Ndzube’s work. Like the shedding snake in Lorde’s poem, weaknesses and trauma of the past must be recognised, consumed and turned into something new.

The Grand Entrance. The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana at Stevenson Gallery; Photograph Simphiwe Ndzube, courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam, Cape Town and Johannesburg

The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana. The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana at Stevenson Gallery; Photograph Simphiwe Ndzube, courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Ndzube’s work is not finished growing either. His characters have a “strong desire to adapt, transform and begin to take up space beyond the canvas”. They go “far beyond the visual zone that they inhabit. This isn’t necessarily limited to the gallery space.”

Magwaza, 2021. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

Notumato, 2021. Like the Snake that Fed the Chameleon at Nicodim Gallery; Photograph courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery

With the recent inclusion of a soundscape by Thabo K Makgolo and Zimbini Makwethu in The Fantastic Ride to Gwadana, Ndzube’s world is fast expanding. Invoking the sonic version of “sorcery, witch-hunting and creatures that fly at night”, the addition of sound further envelopes gallery visitors in the inclusive, playful world of Mine Moon.

Ndzube spoke on the Carla podcast about his next move: trying his hand at the moving image, in the form of video art. Who knows what kind of playful protest Ndzube’s world will introduce us to next? DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.