ANCIENT JOURNEYS

Across the Sahara to Mali: Ibn Battuta’s never-ending trip

In the 14th century, Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Berber-Moroccan scholar, jurist and explorer started a journey from Morocco into the Western Sahara desert.

People of Africa didn’t need to describe the continent: they lived there. So almost every book or report up until the 20th century came from European adventurers venturing into a continent that was dark only to themselves. They made notes and sketches that, often without realising it, opened the way for colonial incursions. Ibn Battuta was different. He came from Tangier in Morocco and most fully embodied Lau Tzu’s notion of a good traveller having ‘no fixed plans and not intent on arriving.’ Battuta travelled almost continuously for 30 years. He began his journey as a haj to Mecca in 1325. After that, he just kept going. This is his final trip: across the Sahara to Mali.

Salt caravan routes across the Sahara in the 14th century. Photo: supplied

***

In 1352 Ibn Battuta, with newly-bought camels and supplies, joined a caravan leaving from Sijilmasa in southern Morocco and headed out into the Western Sahara desert.

Ibn Battuta. Illustration supplied.

“There were no trees, nothing but sand, he wrote, “but in the sand, salt.” They arrived at the mines of Taghaza, a place plagued by flies where everyone was a slave, living on dates, camel meat and millet.

Conditions in the mines were horrendous and the place swarmed with lice. But the salt, he noted, was bought with “an enormous figure” of gold dust mined further south. Its source tantalised him.

Ever eager to move, Battuta tended to go on ahead of the caravan. But when one of his party got lost in the trackless desert he abandoned that practice.

To ensure there was sufficient water, a man would be sent ahead to alert an oasis and water would be dispatched. If he became lost, the whole caravan could perish. “The desert is haunted by demons who will disorder his mind so he loses his way and perishes,” Battuta was told.

Photo: Andrzej Kryszpiniuk/Unsplash

After two months in the pitiless desert the caravan reached the town of Walata. All he was given by its chief was half a calabash of camel milk. He was so insulted by this meanness that he decided to return to Morocco with the next caravan. However itchy feet won out and he resolved to first visit the kingdom of Mali.

Further south he came across a great river he claimed was the Nile, but would have been the Niger. Deciding to wash, he found to his annoyance that a local man kept getting in the way. He later found out the man was placing himself between Battuta and a large crocodile.

Further south, a more hospitable local chief offered his party food, but it made them ill and one of them died. Battuta “fainted over morning prayers and was ill for two months”.

Though a religious man, Battuta found the zeal of the local Muslims excessive. They forced their own children to learn the Koran by heart and kept them in chains until they did. He was also surprised to discover that women servants, slave girls and even the sultan’s daughters went about “without a stitch of clothing on them”. This practice, he said, gave him great pleasure.

On the banks of the river, Battuta came across “beasts with enormous bodies”, which he was told were hippos. He described them as “bulkier than horses, have manes and tails and their heads are like horse’s but their feet are like an elephant. The men were afraid of them but also spear and ate them.

While he was a guest of a sultan in Jenne, they were visited by cannibals “wrapped in silk mantles and suppliers of gold”. The sultan received them with honour and gave them a gift of a woman servant. “They killed and ate her, which is their custom,” he noted without comment, “relishing the palm of her hands and her breasts.”

***

Battuta reached Timbuktu, which did not impress him, then sailed down the Niger in a dugout canoe, trading food for salt, spices and beads as he went.

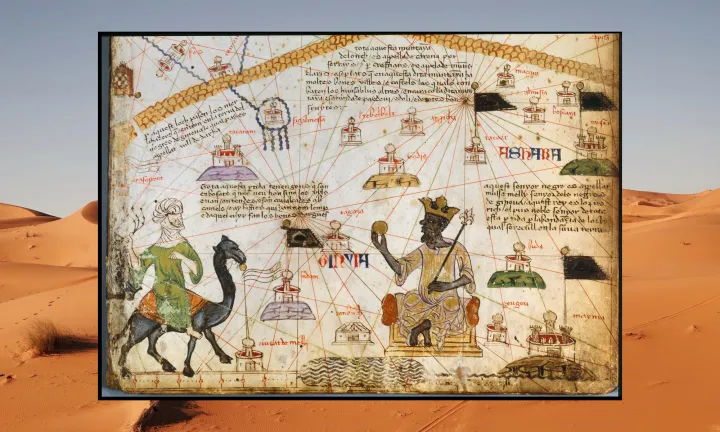

A depiction of Battuta’s arrival at a sultan’s court. Source: Ottoman Imperial Archives

At about this point he decided it was time to head home. In 1353 he joined a caravan that included 600 women slaves – a little-documented aspect of the Arab slave trade. Its route was straight through central Sahara, taking 15 days to reach the oasis town of Ghat, in present-day Libya. The water there, he said, flowed over iron and turned white cloth black.

Further north they met Berbers, who he found “a rascally lot”, and moved on to the town of Buda where he found to his disgust, the people subsisted on poor dates and locusts, which they store just like dates and use as food. “They catch them before dawn because they are too cold to fly.”

Turning west, Battuta crossed present-day Algeria to Fez, the capital city of his home country, Morocco. Clearly relieved to be home and seemingly unimpressed with much of West Africa, he “kissed the beneficent hand of the sultan and settled down, never to leave again”.

Wishing to hear of his travels, the sultan was horrified to discover that Battuta had not taken any notes. He insisted that they be written and assigned a poet, Ibn Juzayy, to work with Battuta who, from memory, described the experiences he’d accumulated over almost 30 years. Together they created the Rihla, the account of Battuta’s travels.

***

His narrative begins, “I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveller in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose party I might join. So I braced my resolution to quit all my dear ones, female and male, and forsook my home as birds forsake their nests.”

He had left home at 22 and visited 44 countries, including China and present-day Tanzania, journeying an estimated 120,000 kilometres.

The transcription was completed in 1355 with the words: “Here ends the travel narrative entitled A Donation to those interested in the Curiosities of the Cities and Marvels of the Way.”

Battuta went on to work as a judge in Morocco until his death in the late 1360s. He remains one of the world’s greatest explorers. DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

So love this quote from this story’s intro: Lau Tzu’s notion of a good traveller having ‘no fixed plans and not intent on arriving.’ And what a fascinating read. Thanks.