US CULTURE WARS

Dr Seuss on the chopping block: It’s a cancel culture thing, says Republican Party right wing

Some of Dr Seuss’s books are being withdrawn from future sale because they are said to demonstrate demeaning and insulting ethnic stereotypes. Not surprisingly, the Republican Party right wing is waving this development around as a tangible expression of the evils of woke and cancel culture movements. Really.

More than 40 years ago, when I helped manage the US libraries in Johannesburg and Soweto, we tried hard to have a good, albeit limited, mix of important US works of fiction, volumes on current, even contentious, non-fiction topics, crucial reference works, and a wide variety of major US periodicals. All of this, of course, was decades before the internet, and printed material was king. But one thing we also subscribed to was a uniquely South African periodical, the lugubrious title of which was usually shortened to Jacobsen’s Index.

This publication listed everything the censors of the old apartheid regime believed to be anathema to its puritanical, strict, racially segregated society. In it one would find every book, magazine, T-shirt, car bumper sticker, record album, film, poster, and anything else deemed a violation of the censors’ overzealous attention. To possess such materials, once listed, became an actionable offence.

As a result, while the periodic listings could easily generate a giggle or a guffaw, such as the listing of the children’s classic story Black Beauty (the censors clearly had no sense of proportion or irony), the listings provided us with a guideline over whether or not we might order and put on our shelves potentially problematic items. Other libraries throughout South Africa, diplomatic enclaves or not, assiduously followed the restrictions in the index. As a result, travellers overseas would buy banned books, wrap them carefully in their luggage, perhaps removing the cover just to be safe, and smuggle them into the country and pass them around among friends, almost like samizdat literature in the former Soviet Union.

The reasoning was a simple, albeit intellectually and ideologically treacherous, one. If we had Ebony (a leading US magazine perpetually on the forbidden list) available to readers, the man who we assumed was from the Special Branch who was always in the library, would note the identities of readers and give them difficulties after they left our libraries. This was, of course, a slippery slope and eventually we all agreed this kind of decision was so antithetical to what we said we stood for and began to stock Ebony and Jet, along with various other items of African-American life, without reservation, although we didn’t let those magazines get lent out — probably for the quite reasonable fear they would never be returned. Such forbidden work had great cachet with readers, obviously.

This experience, and the intellectually torturous rationale for it, helped give this writer a particularly ferocious opposition to censorship, except in the most limited and carefully articulated of circumstances. A public library probably shouldn’t lend the writings of the Marquis de Sade to preteens, but such works should be kept on the shelves of a comprehensive library with a good international literature section — together with essays about and critiques of the man and his work.

This sensibility about censorship is why this writer has been so astounded by the decision to cease publication of six of Dr Seuss’s children’s books. Dr Seuss? Really? Dr Seuss’s real name was Theodor Seuss Geisel but many millions only know him by his pen name, of course.

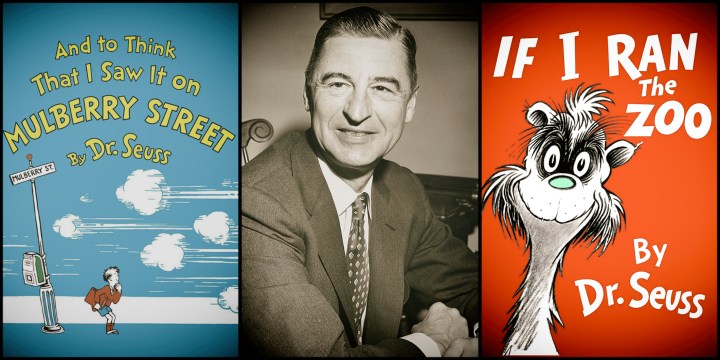

Technically, there has been no board of censors that rounded up the millions of copies of Dr Seuss’s writings to be heaped up for giant bonfires in the fashion of the Inquisition, the Nazis, or the old Soviet Union or Mao’s China, with the authors or their heirs forced to recant their views. But Geisel’s heirs have now determined that six of the author’s works, including his first book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, would no longer be available to be printed and sold by their publishers. Extant copies will continue to be sold and resold, now as collector’s items.

As ABC News reported the decision, “Six Dr. Seuss books – including ‘And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street’ and ‘If I Ran the Zoo’ – will stop being published because of racist and insensitive imagery, the business that preserves and protects the author’s legacy said Tuesday.

“‘These books portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong,’ Dr Seuss Enterprises told The Associated Press in a statement that coincided with the late author and illustrator’s birthday.

“‘Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ catalog represents and supports all communities and families,’ it said. The other books affected are ‘McElligot’s Pool,’ ‘On Beyond Zebra!,’ ‘Scrambled Eggs Super!,’ and ‘The Cat’s Quizzer.’

“The decision to cease publication and sales of the books was made last year after months of discussion, the company, which was founded by Seuss’ family, told AP.

“‘Dr Seuss Enterprises listened and took feedback from our audiences including teachers, academics and specialists in the field as part of our review process. We then worked with a panel of experts, including educators, to review our catalog of titles,’ it said.” Well, okay, then. Case closed? Not so fast, perhaps.

Much of children’s literature – and especially the many books by Dr Seuss – is a perpetual cash cow for publishers. Some of Dr Seuss’s books, such as The Cat in the Hat, One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish and Oh, The Places You’ll Go! have ongoing sales in the hundreds of thousands of copies per year. Meanwhile, works like Horton Hears a Who! and How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, along with that top hat-wearing cat, have become beloved animated cartoons for millions as well.

Reporting on the growing squabble, The New York Times reported, “Classic children’s books are perennial bestsellers and an important revenue stream for publishers. Last year, more than 338,000 copies of ‘Green Eggs and Ham’ were sold across the United States, according to NPD BookScan, which tracks the sale of physical books at most retailers. ‘One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish’ sold more than 311,000 copies, and ‘Oh, the Places You’ll Go!’ – always popular as a high school graduation gift – sold more than 513,000 copies.”

But the now-withdrawn books, including Mulberry Street, have not been selling much in recent years, with that volume only achieving about 5,000 sales last year, although with the decision to discontinue publication, the street value of resold copies of the now-so-disgraced volumes is shooting up dramatically. Still, the question arises as to why this decision is becoming a divisive social issue right in the midst of major, overlapping national crises.

This particular book, and the rationale for it being withdrawn, merits more discussion than simply letting the angry screams of right-wing commentators about this mysterious thing called the “cancel culture”, social criticism that is despoiling everything that isn’t firmly in line with the most progressive “woke” thinking. The heirs’ decision has come from their review of the entire Dr Seuss oeuvre, but the Mulberry Street determination seems to have come specifically from the stereotyped depiction of a Chinese person. The conceit of the book, for those who don’t remember reading and rereading it from their childhood, is of a young boy who sees a parade of people and things coming down an ordinary city street that becomes increasingly more outlandish and bizarre as he watches in open-mouthed wonder. In particular, as part of that larger procession, there is a Chinese man running down the street, wearing a traditional Asian farmer’s conical hat. He sports a plaited pigtail of his hair; he is wearing wooden clogs; and, as he runs, he is holding a bowl from which he is eating his meal with chopsticks.

Now obviously, collectively, these could be read as disparaging, stereotypical attributes of China and the Chinese. But, back in the 1930s when he wrote the book, it was certainly not uncommon in popular culture elsewhere to depict someone from China as wearing a conical hat and wooden clogs, since so many millions of people actually did so. Similarly, eating with chopsticks is, after all, ubiquitous throughout East Asia, and remains so. And as for that egregious pigtail, well, historically, the Ching dynasty that ruled China for hundreds of years until the early 20th century had actually required all male Chinese – at home or abroad – to bind their hair that way as a visible demonstration of fealty to the Ching emperor. Many Chinese probably continued to do so for some years after the 1912 revolution, from long force of habit, although many others publicly cut them off to demonstrate support for Sun Yat Sen’s new government.

Certainly these signifiers, quite common in popular culture in the 1930s in film, by themselves, probably did not merit the death knell of a critique of Dr Seuss’ first big hit, unless it could be shown it represented a deeper reservoir of his cultural and social poison, and that it was deliberately designed to wound. Dr Seuss, after all, had also been a prolific illustrator of World War 2 propaganda posters for the war effort, and some of those illustrations also included rather cruel caricatures of Japanese. But, after all, the Japanese were one of the US’s mortal enemies at the time and such depictions are in keeping with many other propaganda posters.

Yes, some of his books have illustrations that could possibly be read as insulting, or worse, of Africans. But again, they can also be seen as a sign of the times in which the artist/writer lived. Here are clearly areas in some of his books where the author’s apparent biases were in keeping with the common stereotypes of his time.

There have even been a few critics who have chosen to see that famous cat with the headgear as a stand-in for the presumed chaos of black life in the US or Africa. Or something like that. Still, we should also remember that Dr Seuss’s Horton the Elephant should probably be best known for his expression of an all-encompassing humanism, saving the populace of Whoville, when he remonstrated their would-be enemies, “A person’s a person no matter how small.”

But critics of this new publisher’s decision saw something that was deeply malign. Given the red-hot passions among many Americans along the political continuum, not surprisingly, this presumably hard-nosed business decision by Dr Seuss’s heirs and publishers has almost instantly become a cause célèbre among conservative media commentators, the right generally, and among Republicans, all of whom saw this decision as the thin edge of the wedge for the dangers of “woke” and “cancel” cultural trends. This political flouncing around is rapidly turning children’s literature into yet another front in the US culture war.

Amazingly, in the midst of the real Covid and economic crises that continue to grip the nation, senior Republican politicians like Kevin McCarthy, the House Minority Leader and stalwart defender of Trumpism, chose to devote time to sniggering remarks over this publisher’s decision, and in reading aloud from Dr Seuss books to a perplexed nation. That, of course, was instead of doing his real job.

This kerfuffle over Dr Seuss has a bizarre parallel among conservatives as well. Naturally it does. School districts in the US, especially in the South, continue efforts to remove Harper Lee’s perennial bestselling novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, from their respective high school curriculums, and in some places, even from public libraries.

As far as children’s books go, after some of Dr Seuss’s books have gone to the knacker’s shop, can Tintin and Babar be far behind? Or Tarzan? Or an adventure novel like Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, with all its stereotypes about Native Americans, South Asians and more?

As the history.com website describes it, “A school board’s decision to remove To Kill a Mockingbird from Grade 8 curriculums in Biloxi, Mississippi, is the latest in a long line of attempts to ban the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Harper Lee. Since its publication in 1960, the novel about a white lawyer’s defense of a black man against a false rape charge by a white woman has become one of the most frequently challenged books in the U.S.

“According to James LaRue, director of American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, challenges to the book over the past century have usually cited the book’s strong language, discussion of sexuality and rape, and use of the n-word.

“‘The most current challenge to it is among the vaguest ones that I’ve ever heard,’ he says. The Biloxi School Board ‘just says it “makes people uncomfortable.”’ LaRue finds this argument unconvincing, contending ‘the whole point to classics is they challenge the way we think about things.’

“One of the earliest and most prominent challenges was in Hanover County, Virginia, in 1966. In that instance, the school board said it would remove the book from county schools, citing the book’s theme of rape and the charge that the novel was ‘immoral’.

“The board walked back its decision, however, after residents complained about it in letters to local papers. One of the most prominent critics of the decision was Lee herself, who wrote a letter to the editor of the Richmond News Leader. It began: ‘Recently I have received echoes down this way of the Hanover County School Board’s activities, and what I’ve heard makes me wonder if any of its members can read.’” Maybe she was right.

In fact, Harper Lee’s novel is just one of the mainstays of literature that face continuing challenges to allowing students to read them. Huckleberry Finn has been criticised almost since its publication, given its rousing support for the struggle by Jim, the black man with whom Huckleberry travels on the Mississippi River, for his deep desire to gain his freedom – and in Twain’s treatment of Jim as a man with a vast humanity who is the equal of Huckleberry Finn. Catcher in the Rye has often similarly been attacked because of its apparent endorsement for the beginnings of the youth culture and rebellion.

Cancel culture is obviously only a problem when it comes from the left, it would seem, then. Should The Great Gatsby, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, On the Road, or even English classics like Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver’s Travels be left on the shelves despite their obvious subversive messages and meanings?

As far as children’s books go, after some of Dr Seuss’s books have gone to the knacker’s shop, can Tintin and Babar be far behind? Or Tarzan? Or an adventure novel like Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, with all its stereotypes about Native Americans, South Asians and more?

Is there a better way than this? Of course there is. In our view, a book like Mulberry Street should continue to be published, but it should come with a special foreword that gives parents (and young readers as well) the context to understand what might be objectionable and how they should understand and interpret the words, the times, and the ideas. The tales of Brer Rabbit and the Brothers Grimm certainly need some interpretation for modern readers and few have argued for their oblivion. (About now, my wife points out to me that many of those well-loved English nursery rhymes have the subliminal purpose of teaching impressionable children about the so-called natural order of things, learning one’s social and economic station, and in deferring to those of a higher position.)

And even for those absolutely indisputable classics, it is a really rare person in our own time who starts to read a copy of Hamlet or Macbeth (or watches them on stage or screen) without some preparation and introductory and explanatory readings, and, at least at first, the guidance of a good teacher. Children’s books similarly should not be immune to explanation and discussion to keep them accessible and well understood by today’s readers. Warts and all.

Of course, for today’s US, among Republicans and their media allies, the angry critique of the publisher’s decision over Dr Seuss’s six books – rightly or wrongly – is largely a way to keep the cult permanently revved up about the dire intentions of those “woke” and the “cancel culture” devotees and their feckless Democratic allies. And maybe in all this someone is about to launch a Go Fund Me defence fund that will help empty a few pockets for contributions to keep Mulberry Street open for business. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

While this is definitely not a good example of cancel culture, it very much exists and is used by both right wing and left wing supporters, especially to silence viewpoints and debate. Destroying people’s livelihoods for even small political differences as we are seeing now, should not be supported.

Agreed

Niggle: ‘foreword’, not ‘forward’.